It’s 1991, and Paul Haggis, the writer and director of Crash, is carjacked outside a Blockbuster with his wife. Two guys with guns steal his Porsche. He thinks about it a lot—he wonders who they were, how they knew each other, all those questions that remain with a person in the wake of tragedy. Then, 10 years later, in the wake of the tragedy of Sept. 11, Haggis wakes up in the middle of the night and goes to his computer to pound out the outline of what shortly thereafter becomes Crash.

If that sounds like the interesting genesis for a Best Picture-winning feature film, it is—that’s the kind of personal experience that lends itself to the most impassioned filmmaking (and say what you will about Crash, but it is nothing if not impassioned). But for the film that Paul Haggis constructed with that inspiration to have been Crash points to a kind of uncomfortable fact: clearly, the question that stuck with Haggis the longest after being carjacked was one of race. And you know, that itself might be healthy—I think any recognition of implicit bias is an important first step toward righting destructive stereotypes and prejudices. But Crash does not seem to indicate that Haggis went any further than that first step of acknowledging that people have racist tendencies that are socially- and culturally constructed. No, rather than take that idea and mold it into a narrative that challenges us, Crash opts for the path of universalism, the feel-good, we’re-all-in-this-together path that dismisses the unique struggles of people of color in order to assert our collective humanism. The marriage of this superficial theme to the very real issue of racism could only be the product of a man who, while having witnessed racial stereotypes from the side of a wink-and-a-nudge, has himself never experienced the specific pain that stems from racial adversity.

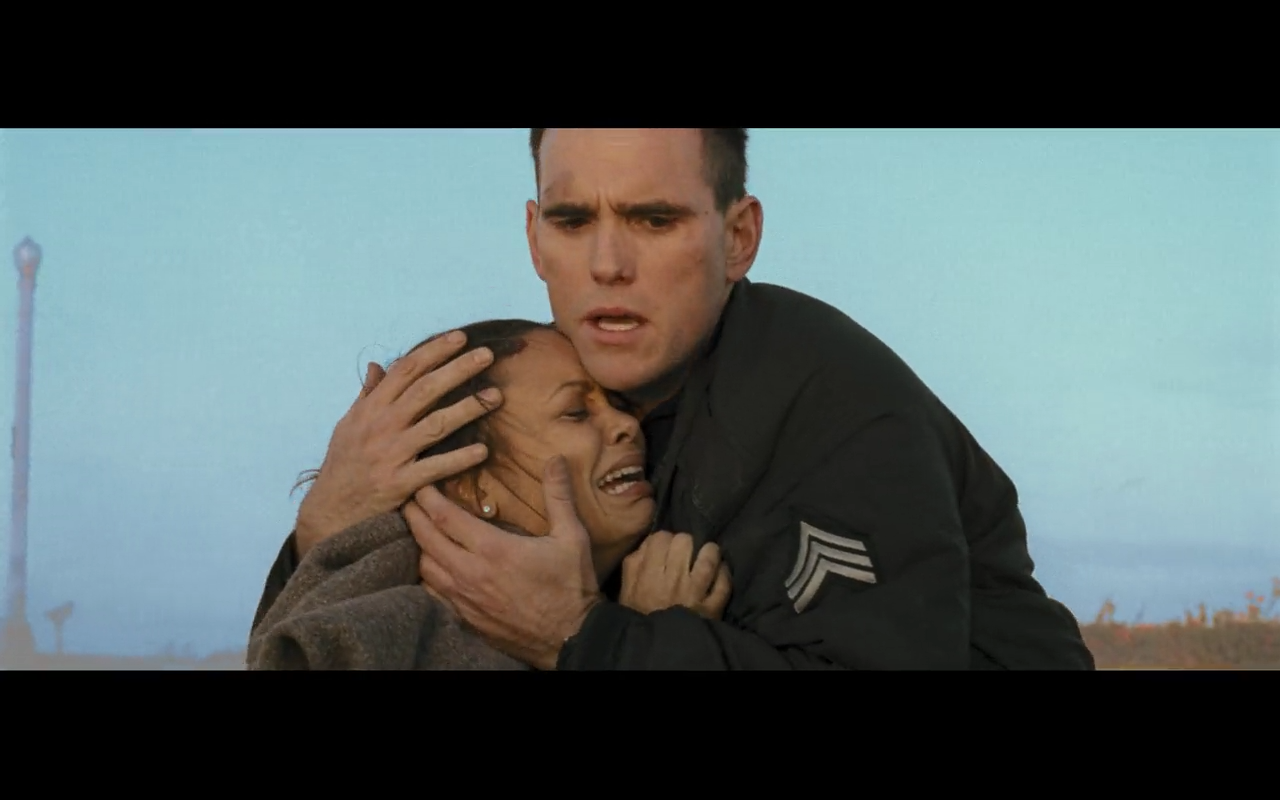

This probably explains why racism in Crash looks like the kind of dictionary racism that even Bill O’Reilly would have to condemn. An old white guy who runs a gun shop refuses to sell a revolver to a Persian man after getting frustrated with him for using his daughter as a translator; in the course of this interaction, he calls the man “Saddam.” A prototypical, snooty white woman (deftly played by Sandra Bullock as a foil to her then-forthcoming Blind Side role) clutches her husband tightly as they pass two black men on the sidewalk. Later, after being carjacked by those black men, she erupts into a painful rant about the man they hire to change the locks on their house, since he is Mexican and has tattoos and will likely copy the house keys to distribute to his gangbanger “homies.” A cop who pulls over a wealthy black couple sexually assaults the wife until her husband begs him to let them go. The same cop later laughs at a woman who helps him on the phone because she tells him her name is Shaniqua, to which he replies, “Shaniqua. Big f****** surprise that is.”

The entire first act of the movie plays racism with a capital “R”, cranking to 11 the stereotypes for which it wants to hold us accountable—oh, you’ll laugh about Asian drivers with your buddies, but how do you feel when it is affirmed within a narrative? But with this, we’re already on uncomfortable ground. It’s not that it’s uncomfortable because these stereotypes are so close to home, but rather that Paul Haggis has never suffered from these stereotypes. That’s the central issue with Crash’s depiction of racism: it’s a white guy’s idea of racism, and a white guy can only cover the topic superficially, no matter how well-intended. Haggis establishes all the biases—both explicit and implicit—of the characters, then moves on. The movie doesn’t show what racism actually does: Haggis’s point is that thinking in terms of race harms all of us, when it should be that thinking about a person as only a member of a race specifically dehumanizes that person. This is the same school of thought from which colorblindness graduated, a philosophy that says that, in order to not be racist, you just have to remember that everyone shares the experience of being a human being. It’s an ideology that automatically absolves the sin of inaction, and in Haggis’s world, it is morally sufficient.

Anyway, the rest of the movie weaves the many characters’ storylines into an intricate web of connections, ostensibly deepening our understanding of who they really are beyond the stereotypes and slurs we’ve seen them throw at people for a half hour. Haggis makes sure that the characters have their racist side, and then their human side; each intersection of their storylines is supposed to show us how their bigotry ultimately harms or restrains their ability to connect to people. Haggis is eager to subvert all our expectations about these characters in what he sees as dramatic twists, but an even tiny dose of cynicism is enough to defuse the oh, wow! factor of these moments. Turns out Sandra Bullock’s angry racist lady is actually very sad! Turns out the Korean guy who got run over wasn’t a victim at all—he was involved in human trafficking! Turns out the cop who was disgusted by the racial profiling shoots a black guy because he thinks he’s got a gun! See, this is what happens when you judge people, man! You get it wrong! In trying to push the flaccid, uninspired theme of our common human experience (ugh), Haggis reduces everything to predictable caricatures that are infuriatingly earnest.

In an interview with Huffington Post, Paul Haggis responded to a challenge about the film’s depiction of racism by saying, “I was obviously creating a fable. That’s obvious. This was never supposed to be a realistic film.” Immediately, this sounds like a cop-out, because beyond the serendipity of its plot, there is little about Crash that isn’t concerned with the grim reality of life in America in the 21st century. He also suggests the flagrant use of stereotypes to establish the characters’ bigotry is supposed to goad the audience into a place of comfort, like the first 30 minutes are supposed to nudge us into laughing at the parade of stereotypes that we are all so comfortable with. In doing this, he underestimates his audience so confidently and with such vulgarity that it forces us to think about where this is all coming from. He says he wants to “bust liberals” with Crash, but really he just seems to expose himself as out of touch, an emblem of a generation that was taught to see “humanity” as superseding the importance of race. As the years wear on, and as our understanding of race grows more complex and more nuanced, his argument that we are all humans first is a slap in the face to people of color, whose experience of humanity is inextricable from that of race.

And all of this criticism of its brazen stupidity brings us back to the bigger component of Crash’s tainted legacy, which is its Best Picture win over Brokeback Mountain. Opinions about the significance of the Academy Awards aside, it is fascinating to consider these two films in competition with each other, because both confront themes of identity and expectation, one with race and the other with homosexuality. It’s fair to posit Brokeback Mountain as a fable, as Haggis did with Crash: Brokeback is a story about two men whose response to a shared experience defines who they are and what their lives become. It is a fable that is understated, that occasionally asks that the viewer fills in the narrative gaps with an assumption. And it does justice to that shared experience that drives the story—it doesn’t betray it by making a sharp thematic turn. Brokeback Mountain indulges its theme to a satisfying and logical conclusion, whereas Crash interchanges its themes to suit the comfort of a white liberal audience. Film history will ultimately remember the picture that was brave with its message.

And in spite of all of my criticisms (as well as those of others), I am still forced to concede that Crash was a wildly successful movie in traditional terms. It won three Academy Awards (with an additional three nominations); it recouped its production budget seven times over; and it made many rich famous people richer and famous-er because of their role in its production. So we kind of have to acknowledge the mass appeal of Haggis’s broad message. And while I do recommend watching Crash, it is primarily as a fascinating lesson in what not to do. In terms of taste and artistry, I see Crash as a textbook argument for abolishing certain trends in cinema, chief among which is white men being the most dominant voices in the industry. As filmmakers like Steve McQueen, Ava Duvernay and Ryan Coogler continue to emerge, illustrating the significance of diverse voices in cinema, it seems that we can allow ourselves some optimism, some hope that good intentions alone will not be enough to carry misguided movies like Crash to term, let alone massive(ly) unearned success. But the journey for non-white filmmakers from anomaly to norm—from niche to mainstream—is ongoing, and it demands that we as viewers demand more from our movies. When you buy a ticket at the theater, you are voting for that movie’s creators as the artists who most deserve your money. It’s important to listen to what they’re saying.

NO COMMENT