LaToya Ruby Frazier is exhausted. She flew in from Braddock, Pennsylvania, to Chicago at the crack of dawn to speak at the Art Institute of Chicago in front of a packed crowd. Today is painless compared to the previous 365 days. She reflects on her weeks in Flint, Michigan, where she documented Flint’s horrific water crisis. The tragedy in Flint exposed tens of thousands of children to high levels of lead. Back in her hometown of Braddock, Frazier’s spent the last month around the clock at the local hospital by her mother’s side in the I.C.U.

“I go where I’m called,” Frazier says, glaring up from her phone to look around the theater before she gets on stage. She slouches in her chair, dark brown bags under her eyes from the night before.

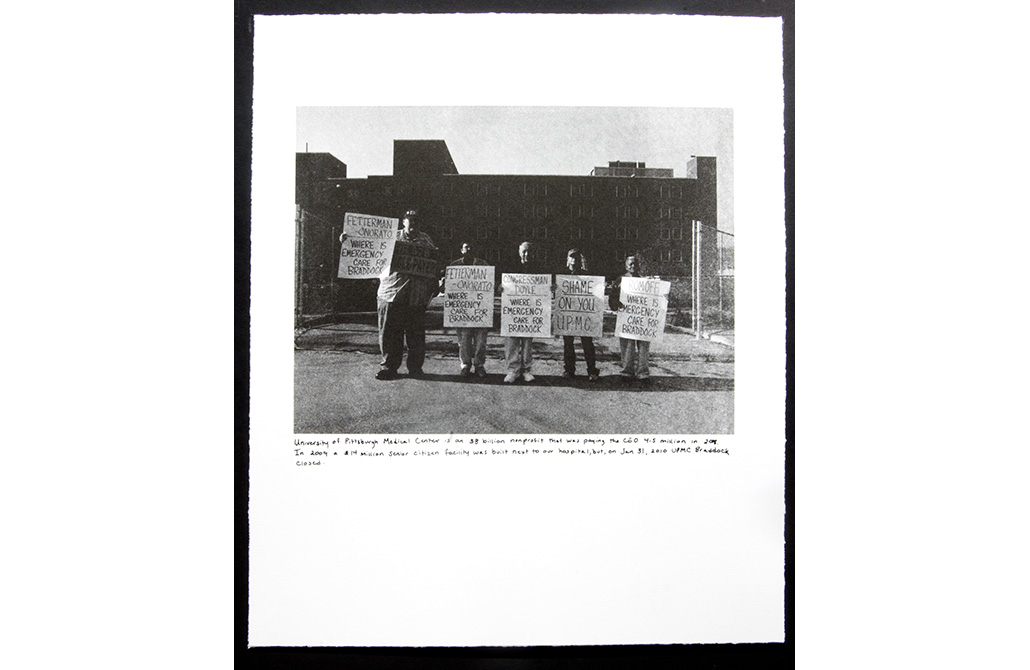

Frazier’s work in art and advocacy is deeply personal. Her photography exhibit in 2012, “Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save our Community Hospital,)” addresses the struggle for economic opportunity and health care by Braddock residents. She shows the crowd printed black-and-white photographs from the project of resident protests outside the demolished hospital in Braddock. One small group of demonstrators outside the hospital holds up signs that demand an answer. “Where is the emergency care for Braddock,” they ask. They’re all fighting for the same thing: equal treatment from the system that’s failed them for generations.

The project also includes old ads from a campaign by Levi’s that Frazier repurposed and transformed to reveal the devastating truth about Braddock’s industrial history. The working class residents in Rust Belt towns such as Braddock still get up every morning and go to work for endless hours at the nearby steel mill despite an economic decline in the steel industry. The recent effects of industrialism and environmental degradation are especially prominent in places like Braddock. The people have seen the steep decline of their communities they call home. In one ad, she makes subtle revisions with a black marker to a phrase that reads “EVERYBODY’S WORK IS EQUALLY IMPORTANT.” Below the ad is a scathing message, “If everyone’s work is equally important then why weren’t local residents and small businesses allowed a share in the profits from the demolition process of the bricks and windows from UPMC Braddock?”

“It’s very clear to me why I started making this work and why it wasn’t hard for me to make these images. I knew that I wanted social justice and a reclamation of the history of Braddock finally being told by the point of view analyzed of women,” she says.

Residents protest outside demolished hospital in Braddock (LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Campaign for Braddock” Exhibit)

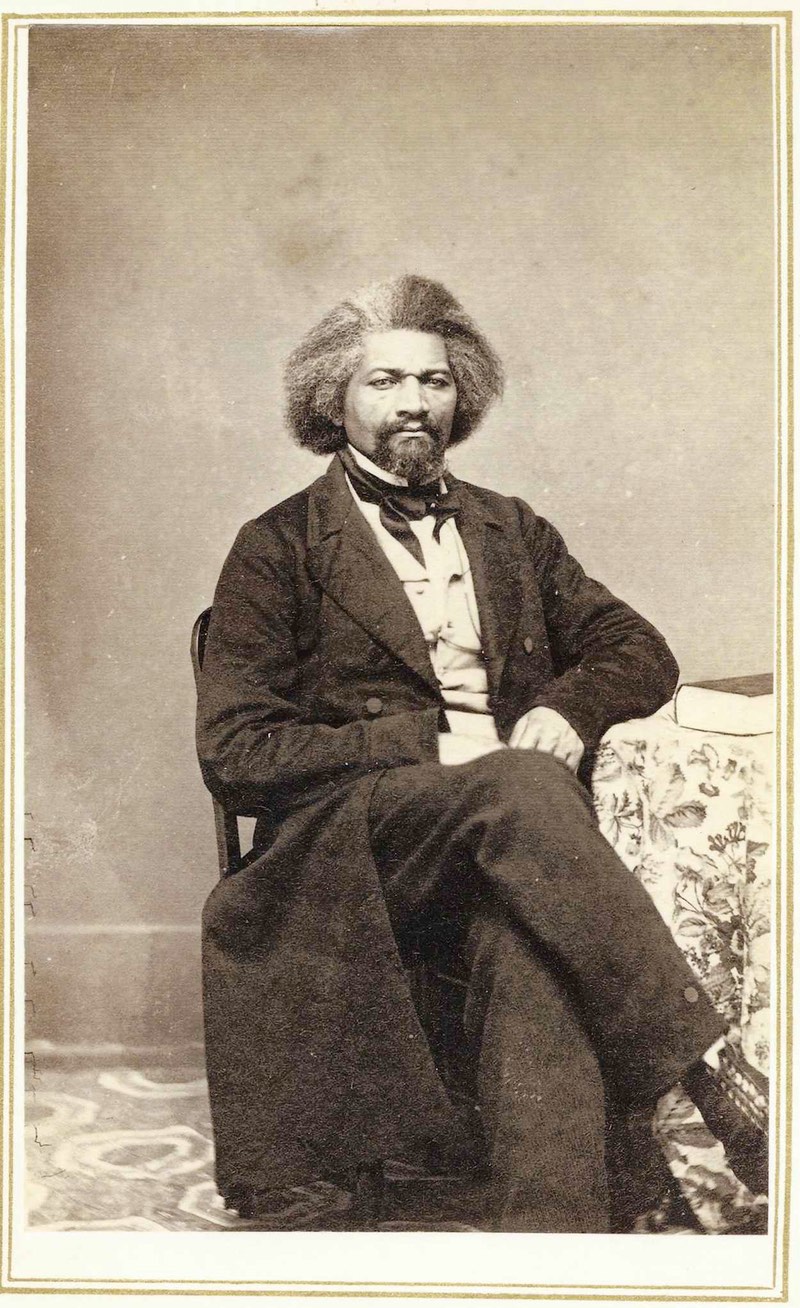

The role of artists in social justice movements is to respond to the political and popular culture around them. Frazier isn’t alone in her fight towards social justice. In the aftermath of the 2016 election, many artists and musicians devoted their art to inform people of important issues. The personal and political problems we discuss today shape and influence the work of most contemporary artists. Their aim is to shift the way people think about the world. This concept isn’t new. Frederick Douglass posed for more portraits during the 1800s than any officer or president, including Abraham Lincoln. He sat for 160 photographs. In most of the black-and-white shots, Douglass pierces through the grainy film, donning a sharp black topcoat and bow tie. Douglass used his portraits to challenge the negative stereotypes of African-Americans, and reflect a more accurate portrayal of race in a crucial time in American history.

Fredrick Douglass poses for a photo in 1863. (Courtesy of Hillsdale College)

“Poets, prophets and reformers are all picture makers — and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements,” Douglass wrote in “The Portable Frederick Douglass.” Douglass believed that photographs could create an accurate representation of some “greater reality.” He even suggested that the social and moral influence of pictures was more significant in forming culture and achieving social justice than actual laws.

This kind of social art continued after Douglass well into the 1900s. In the pre-internet age, mass media only featured a handful of television stations and magazines, but they reached millions of people. Renowned artists and political activists like Norman Mailer regularly appeared on prime-time talk shows. Dick Cavett even welcomed leftist playwright Lillian Hellman on his show to discuss art and politics. James Baldwin and Robert Lowell were both featured on the iconic cover of Time Magazine. It was the first time people could watch live debates from their homes, too. These events changed television news forever. The documentary “Best of Enemies” captures the series of discussions during the Democratic and Republican national conventions between liberal writer Gore Vidal and conservative William F. Buckley. They were nationally broadcasted and considered one of the biggest television events in the 1960s. Politics and art were very much at the center of American culture.

Fast forward to today. Artists preserve the same ability to spark change, connect and alter perceptions. They do this by responding to the changing world around them in the only way they know how: by creating. Like Frazier and her contemporaries. At the same time, artists demand more public attention than any other time in recent history. In November, just before the election, about a thousand distinguished writers signed “An Open Letter to the American People,” speaking out against Donald J. Trump. “Because, as writers, we are particularly aware of the many ways that language can be abused in the name of power,” Andrew Altschul and Mark Slouka wrote.

The responsibility of artists is not to only provide visuals for people, but shift our thoughts through the representation of them. Artists create uncomfortable conversations with their audiences about crucial issues. Look no further than the film industry. The most pivotal movies and documentaries break stereotypes and produce empathy between people.

No film inspired more empathy and action in public than “White Helmets.” The short documentary is named for the group of first responders who rescue victims in the hellish war zones of Aleppo. According to the Netflix documentary, they’ve saved “over 55,000” people and counting. Described as “the story of real-life heroes and impossible hope,” the film earned a Nobel Peace Prize nomination earlier this year. The footage in the film provides both a look into the conditions in Syria and the courage of the White Helmets. One scene shows the White Helmets saving a newborn baby trapped in the rubble of a building bombed in an air strike. This type of footage is vital in the coverage of the crisis. The group has emerged as an essential resource for journalists seeking information on the attacks in Syria.

Khaled Khateeb, the cinematographer who helped film “White Helmets,” was denied entry into the U.S. to come to the Oscars as part of the Muslim ban. Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi joined in protest of the executive order. After winning the award for best short subject film, the director of “White Helmets,” Orlando von Einsiedel, took the stage to read a statement by Khateeb. “It’s very easy for these guys to feel they’re forgotten,” he said. “This war’s been going on for six years. If everyone could just stand up and remind them that we all care, that this war end as quickly as possible. Thank you.”

This year, The Academy nominated four black filmmakers for best documentary feature. Three of the four films are unequivocally about race in America: Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro,” Ava DuVernay’s “13th,” and Ezra Edelman’s Oscar-winning “O.J: Made in America.” The three directors weave together concepts of police brutality, past and present racism, and the black experience. Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro” draws from James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript “Remember This House.” The story explores modern racism through Baldwin’s friends in the Civil Rights Movement, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King, Jr. Peck describes making the film as a response to his frustrations.

“I Am Not Your Negro” considers how America’s perception of race has evolved since D.W. Griffith’s Civil War epic “Birth of a Nation.” Peck looks at race relations and representation in media. Racism is embedded in early American film. DuVernay’s “13th” also explores how in the past Hollywood has promoted propaganda for white supremacy. In the original “Birth of a Nation,” Griffith provides a falsified history of Reconstruction. White actors in blackface depict barbaric villains who take over the South and terrorize whites. The fictionalized black characters are portrayed as rapists and murderers, while the Ku Klux Klan’s painted as heroes of the South. “Birth of a Nation” was the highest-grossing film at the time of its release. The story was used as a recruitment tool for the Klan, whose movement increased upon the success of the movie. If anything, Griffith is proof how powerful art can emerge from vicious ideology, too.

After its release in 1915, then-President Woodrow Wilson invited Griffith to the White House for a screening of “Birth of a Nation.” Wilson’s excerpts even appear in the film to defend Griffith’s made-up version of Reconstruction. He praised the film, claiming it was “like writing history with lightning.” It was the first film ever screened at The White House.

And yet there’s still an illusion that art is powerless in American life. In fact, the late poet W.H Auden claimed that “poetry makes nothing happen,” during a previous time of crisis. Auden believed that writers and artists were incapable of creating political or societal change. And to some extent, it’s a reasonable argument. How does a documentary about Flint help improve the conditions of Flint? Auden and other skeptics would say it doesn’t. “As far as the course of political events is concerned they might just as well have done nothing,” he notes in his unpublished meditations. This notion suggests that we can only oppose acts of injustice as citizens, and not artists. But the idea that art plays no role in political culture undermines the work of contemporary artists like Peck and DuVernay. It’s largely an inaccurate narrative. Good art can be a personal experience, and still address politics at the same time. According to Adam Kirsch of Slate, “that is why great political art is so often about the experience of dread and loss.” Sure, artists’ ability to sway major elections or prevent crises is an unrealistic responsibility. But that doesn’t mean art is powerless.

During her lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she also teaches photography courses, Frazier spoke about issues of race and class, social justice and identity. These issues influence Frazier’s work in photography and visual art. She expresses her concerns about the future of health care. Her mother received coverage through the Affordable Care Act the last six years.

“I have a heavy heart today because I’m very concerned about the state of health care in this country,” she explains, pacing up and down the stage. “I keep having a clash with the healthcare system, in particular, UPMC. So this became very important to deal with these mixed messages that are going on right now.”

According to The Hill, repealing the Affordable Care Act without a replacement could leave 18 million people without health insurance the following year. Frazier’s mother could be one of them.

Frazier’s encouraged that more publications are socially engaged. Her “Flint is Family” piece in Elle Magazine, released the same day FEMA cut support for Flint, features a collection of powerful images and visuals from her time there. One striking image shows a young mother pour bottled water into her daughter’s mouth to brush her teeth. The image’s inspired by Frazier’s favorite photograph, a 1968 cover in LIFE for “A Harlem Family” feature by Gordon Parks. She marvels at the similarities between the two images.

Frazier provides a strong message to people in the crowd who use social media.

“For those of you that use social media, it’s one thing to use it to put out an ad or fake version of yourself. But imagine if everyone photographed the reality of what was going on in their communities,” she says.

How can art create social change? Well, Frazier’s work informs and reminds people of crucial issues around the nation. Art and advocacy are a form of relief too. When Frazier visited Flint in July, she met Shea Cobb, a young singer with a daughter, Zion. The water crisis affected Cobb’s entire family. Shea’s skin broke out in a horrible rash. Zion complained the smell of the dirty tap water made her nauseous. Shea’s mother’s hair was falling out in clumps. When Frazier watched Shea record at a local studio, though, she noticed a different side of her. Release. When Shea records in the booth, she tunes everything else out. It’s the only time where she doesn’t have to think about the destruction around her. She doesn’t have to cry. She doesn’t have to worry about where to get clean water. She can be at peace for now.

Header image: NAACP Protesters outside theater premiering “Birth of a Nation”

NO COMMENT