On a calm, tree-lined block of Superior Street on Chicago’s West Side rests the Ukrainian National Museum. From the entrance, visitors can count the steeples of nearby churches that anchor the surrounding neighborhood of Ukrainian Village.

An attendant greets guests inside the museum and leads them to an expansive room updated monthly, full of silky floral dresses and color contrasted paintings of nature. Upstairs is the permanent collection, consisting of musical instruments, painted eggs, portraits and more garments.

While the Art Institute, Field Museum and Museum of Science and Industry are world-class museums that validate Chicago’s culture, other smaller museums separate from these grand institutions — like the Ukrainian National Museum — contribute to the city’s cultural fabric.

As part of the Chicago Cultural Alliance (CCA), the Ukrainian National Museum is one of 35 organizations representing 28 countries through historical societies, museums and cultural centers that reflect the history of Chicago as an immigrant city. Many of these museums were established and continue to operate in the same neighborhoods where immigrants settled. The Ukrainian National Museum and the nearby Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, both members of the CCA, are located in Chicago’s Ukrainian Village.

At the Ukrainian National Museum, curator Maria Klimchak says people who came from displaced persons camps after World War II founded the museum in 1952 to preserve the history of Ukrainian diaspora. It is the oldest and largest Ukrainian cultural institute in the United States, according to Klimchak.

While now she works as a full-time curator with a salary, Klimchak said the museum relied on efforts from volunteers since the beginning. She came to Chicago from Lviv 24 years ago in a wave of immigrants after Ukraine declared independence in 1991.

Curator Maria Klimchak, Ukranian National Museum, invites people to see the beauty of her country. Photo: Michael Schmidt

“I would like to invite people to own my own country,” Klimchak said. She walked through the upstairs hallway, passing rooms each filled with specific exhibits – coins, postcards, maps and newspapers. “I would like to tell the people’s story of a great country. It’s a peaceful country.”

Klimchak is a first-generation immigrant from Ukraine from the fourth and most recent wave. Previous waves occurred before World War I, between both World Wars and after World War II. One of her favorite exhibits is dedicated to the Ukrainian diaspora, a solemn display that details the wars and famines surrounding the waves of immigrants through displayed newspaper articles, posters and poems.

“Chicago is a fantastic museum city. In the Chicago Cultural Alliance we support each other,” Klimchak said. “It’s a wonderful experience to go to the other cultural museums. For example, the Polish museum – our culture is similar to that culture. Historically it’s different but you can have programs in common.”

According to Klimchak, the only two ethnic communities in Chicago that offer ten years of Saturday school language classes for students are the Polish and Ukrainian.

“With five hours every Saturday, learning the Ukrainian language in school, it’s hard to support this,” Klimchak said, “but when you are older you appreciate it because you speak another language and can communicate in your grandmother and grandfather’s language.”

Klimchak opened a heavy glass display case that holds one of the most popular exhibits: the pysanky, Ukrainian Easter eggs. Each pysanka is painted in colors that reflect various messages – red for sun, happiness and hope, orange for endurance and strength.

“They send messages of how to be happy, how to love,” Klimchak said, carefully closing the display box. “Instead of sending postcards, you are giving people Easter eggs to wish good luck.”

The pysanka is one medium of tailored art forms unique to Ukrainian culture. Inside these cultural museums, there remains the intrinsic value to preserve culture in various styles. In Andersonville on the North Side, the Swedish American Museum on Clark Street serves another example.

Executive director Karin Abercrombie, Swedish American Museum, poses in front of the Swedish immigration exhibit. Photo: Michael Schmidt

“Our mission is to continue to preserve the Swedish heritage, language and culture,” executive director Karin Abercrombie said. “We do that through programs and events along with just having the museum open.”

Abercrombie’s job is essentially the chief operating officer of the whole museum, which differs from a curator role of being in charge of specifically the collections and exhibits.

“We have language classes in the evenings, we do lectures around Swedish topics, we do concerts with Swedish music and at times we do movie series to show Swedish movies,” she said. “Around Christmas we have children’s activities too.”

The Swedish American Museum also tries to incorporate the outdoors when possible. Abercrombie said in Sweden, there is an idea called “allemansrätten,” or freedom to roam.

“It’s basically everyone’s right to be out in the woods. You have to respect it,” Abercrombie said. “People love being out in nature, especially because wintertime is gray, but then spring and fall come around. There’s a lot of berries and mushrooms growing that people like to pick, hunting, all of that.”

With Chicago, it can be difficult to uphold this value of nature in the middle of a large urban environment experiencing winter for most of the year. But the museum adapts by emphasizing community gardens and farmers markets. The museum had a spring exhibit about sustainable housing, reflecting the values of Sweden.

“We try to showcase that Sweden isn’t just Abba and meatballs and pancakes, but that there’s something different than that,” Abercrombie said. “There’s always a fun way to be able to show that there’s something more from the country.”

This goal manifests in many of the CCA museums’ missions. They are united in their efforts to welcome others into the art and culture of their countries.

“Our member museums are broadly concerned with cultural heritage, which is rooted in place, people and tradition,” said Izabela Grobelna, the community engagement coordinator for the CCA, “all of which encompasses identifying markers of cultural celebration, traditional dress, historical artifacts and the production of art from past to now.”

Grobelna noted that before all these cultural institutes were bound together by the CCA, anthropologists at the Field Museum ran an education program called Cultural Connections. Through those public programs, the museums had a chance to meet and start formulating a collective.

Chicago Cultural Alliance

A map of the countries whose cultures are represented in the museums featured in the Chicago Cultural Alliance.

“It is an effort of community building and less so of attracting tourists,” Grobelna said. “And localizing the museum in the neighborhood often goes hand in hand with connecting to the immigrant or cultural communities.”

Through neighborhood activities, festivals and accessibility to immigrant communities, localization is a primary method of engagement. This is the case for many core members of the CCA – like the South Side Community Art Center and Bronzeville Historical Society based in Bronzeville, the Indo-American Heritage Museum in West Ridge and Latinos Progresando and Casa Michoacán in Little Village in Pilsen.

Members of the CCA must go through a formal application process according to Grobelna, and these organizations must be rooted in community and represent a specific culture. However, some cultural centers operate outside of this membership. The National Museum of Mexican Art is one of these institutions.

The museum, located within Pilsen’s Harrison Park, was started by educators in Chicago Public Schools who noticed students slipping through the school system without knowledge of their roots, according to curator Rebecca Meyers. She recalled how the museum developed out of its grassroots organization of Mexican cultural events and poetry reading into a museum that has tripled in size since its opening in 1982.

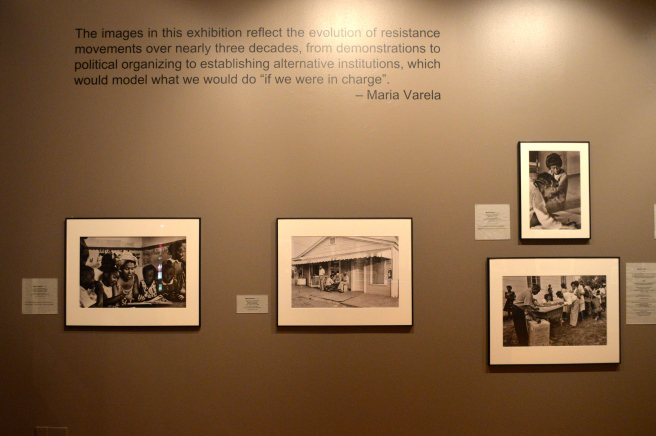

A photography exhibit shows the strife of resistance movements at the National Museum of Mexican Art. Photo: Michael Schmidt

“We are a country of immigrants, and often their stories are not told in history books,” Meyers said. “We don’t know about indigenous cultures because of that. We would have a lot less racial and cultural strife if we were more understanding.”

One of Meyers’s favorite moments in her career was when one child visitor was enlightened after his first visit.

“We were in the gallery, and this very street smart kid came up and said, ‘You have the really real stuff in the back, right? You wouldn’t be putting this stuff out here.’ But you could see his face light up when we said it was all really from Mexico,” Meyers reminisced. “Maybe this boy went home and brought his parents.”

Meyers studied fine arts at University of Illinois Chicago in hopes of becoming a “sculptor-painter-art maker.” But after her first trip to Mexico, she decided to concentrate on Latin-American art history and took graduate school classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, which altogether led her to her curator position. Even though Meyers is not of Mexican descent, she seeks to bridge cultures together through her work to reach the goal of greater understanding.

At the Swedish American Museum, Abercrombie agrees that membership within that community is not a prerequisite for visiting a given cultural center.

“There’s still people in the neighborhood that have never been through our doors because they’re like, ‘oh I’m not Swedish.’ You don’t have to be Swedish to like art,” Abercrombie laughed. “That’s why we try to vary our exhibits from photographs to sustainable housing. It ties to everything, not just Swedes.”

“I want to show how the people and country of Ukraine are great,” Klimchak said. “I would like to invite everyone to see the culture and recognize us by character. Why did we come to the U.S. with no language, no knowledge? What is our story? We will never give up.”

In Pilsen outside of the National Museum of Mexican Art, a school bus driver waits for children to finish their field trip. Young students leave the entrance in smiles, jumps and dances. The mission of the museum lives on.

Header photo: Traditional pysankas. Photo by Michael Schmidt

NO COMMENT