A look inside Chicago’s Streeting community

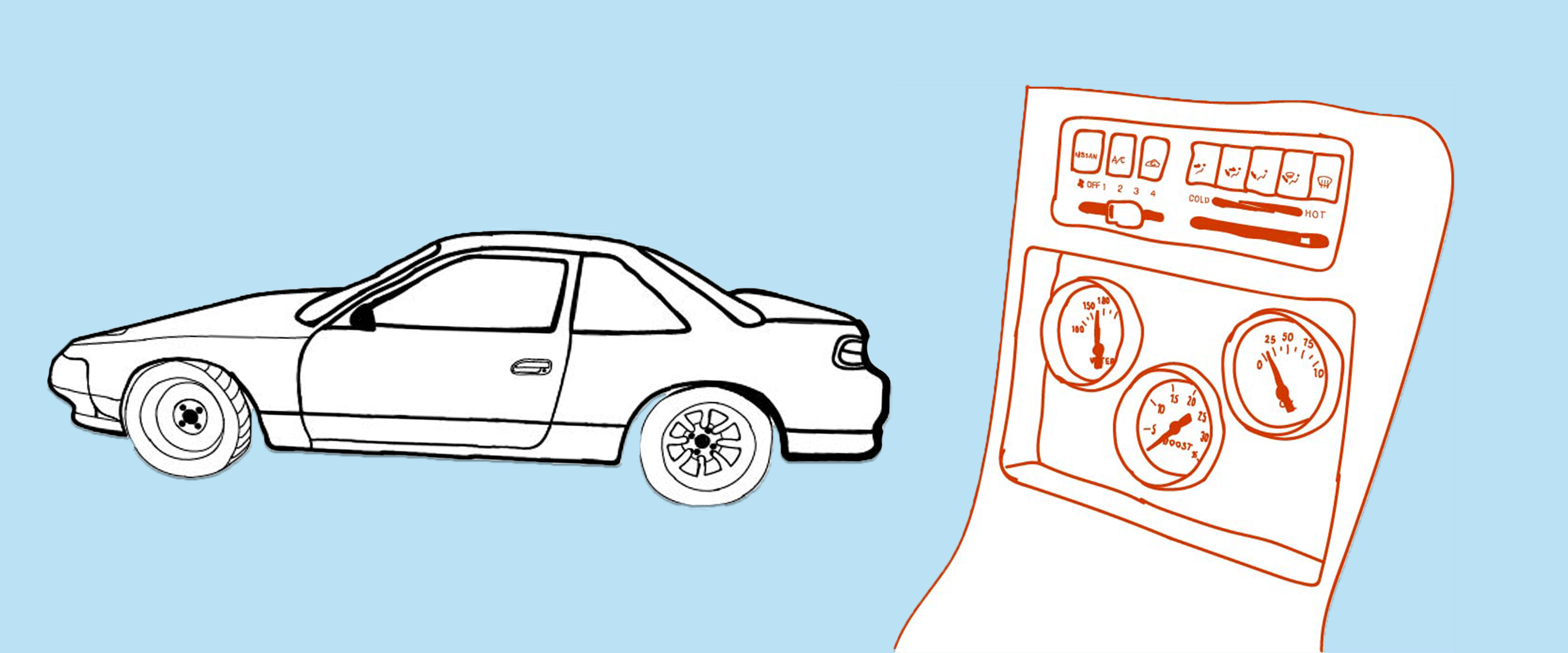

I lower myself with difficulty into Karl’s 1990 Nissan Silvia 240SX and watch as the seatbelt automatically buckles me in, no hands required. In the drifting community, the lower the better. The car itself has just been driven from Virginia to Illinois where Karl plans on streeting it.

Illustration by Sam Smith.

Streeting, in layman’s terms, is the act of drifting on, well, a street. Any street that has enough bends in it to accommodate the sliding of the car from one end to the other is a dream. As opposed to street racing or the drifting you see on the track, streeting isn’t about competing. It focuses on style, culture and having fun while driving.

Like the strokes of a paintbrush, the swiveling of the wheel is carefully and meticulously drawn out to rotate the car perfectly. It truly is an art form, and that’s coming from someone who previously had no knowledge of cars—seriously, I once poured engine fluid where wiper fluid should have gone.

“I just kind of bomb into a corner as fast as I can and then just like flick the car into it and then,” Anthony, an avid drifter, claps before going on, “kind of happens. To me, it’s part of driving.”

According to Drive Tribe, a blog dedicated to cars and driving, Japanese drifting culture originated in the mid-‘80s with the so-called “Drift King” Keiichi Tsuchiya. A short film called “Pluspy” highlighted his drifting skills and caused drifting to popularize throughout Japan.

Drifting then made its way to the US and became popularized through “The Fast and the Furious” franchise, out in 2001. These movies centered around driving as fast and reckless as possible, misrepresenting the original style in Japan. This is the biggest cause for tension among the car community in the US, as many aren’t aware of the technique and skill required for drifting.

Drift competitions now live in the US as well. One event, Final Bout, is a weekend long competition to find out who can drift the best. The drivers go out in teams and drift in tandem with one another. They’re judged based mainly on style of car and drift, and the more Japanese inspired the better! There are four competitions, three held in the US and one in Japan. The Midwest competition features a few teams from Illinois.

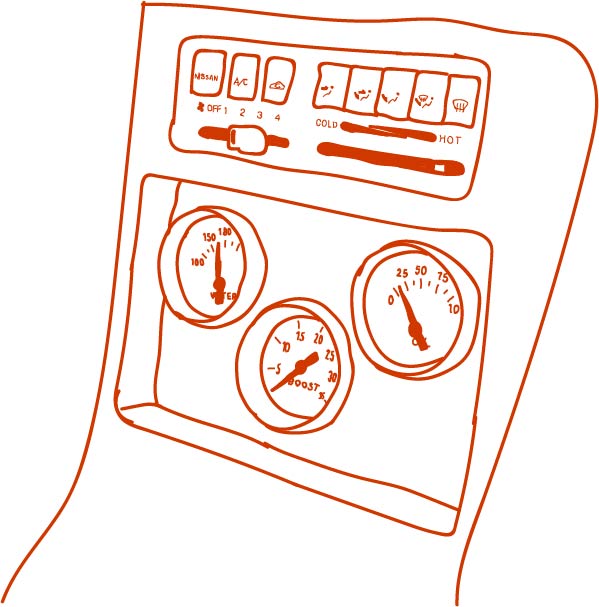

It takes a level of skill and concentration to be able to swivel your car from side to side, which is why Karl doesn’t listen to music while driving. His attention is completely on the road. Even if he wanted to listen, there are dials for a turbo where his radio should be, so his only option is a bluetooth speaker connected to the cage behind him.

Illustration by Sam Smith.

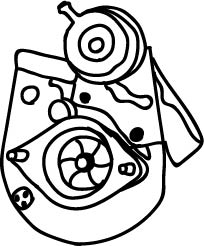

The turbo isn’t necessary for drifting; in fact, it’s more suitable for drag racing. It’s simply there to recycle exhaust from the engine and funnel it back to create more power. But power isn’t necessary for the art, it’s just a preference for those who crave the extra boost.

Illustration by Sam Smith.

“If you can’t drift with 90 horsepower, 400 horsepower ain’t gonna help you.” Karl said.

The cage, however, is a huge aspect of safety that goes into any professional drift car, as well as some street cars, like Karl’s 240SX. “The whole body of a car, as you go over bumps and stuff, like believe it or not, it’s actually twisting and flexing all the time,” Karl said.

Although cars are made of metal, if one flips there’s not much to prevent it from crushing someone inside. Therefore, a cage is used to hold the car to its shape in an accident. Karl’s takes up the entirety of the back seat and has an ‘I love the nineties’ sticker on it.

While turbos and cages come in handy, they aren’t essential for streeting. There are only a few things that you need to drift. First: rear wheel drive. “Think of it as a shopping cart. Unless you really whip it around the corner, the back wheels aren’t gonna move,” Karl told me, “but if you’re pushing a shopping cart you can easily make it slide all over the place.”

The second feature that cars need to drift is a differential that isn’t open. A differential basically controls the spinning of the wheels, and a closed differential locks them up so they gain traction and the car moves forward. All you need to know is that with an open differential your back tires will keep spinning and you’ll end up in dizzying circles, probably doing a burnout.

“There’s not really any specific rules for it unless you’re with your group of people you’re comfortable driving with,” Anthony said, “because obviously you wanna learn other people’s driving styles if you’re gonna be comfortable driving inches from their door.”

That’s what’s called tandeming in the world of drift. Going in tandem with someone is more of a bonding experience than anything. “You learn their style and then you eventually try to get on their door while they’re sliding and keep the same line they have,” Anthony said.

There’s more reason to go in groups than just to tandem with them. It’s also a tactic to keep out of trouble. The mindset is basically: they can’t catch us all!

If caught drifting on the street, you can get a ticket for reckless driving. According to the Illinois Reckless Driving website, your license can be suspended if you already have two strikes against you. Anthony’s been busted for streeting before. For six months, his license was suspended and he had a driving curfew in place after that. He doesn’t seem too upset over it, though, simply calling it “dumb.”

There are a few cars that make for ideal drift cars. Karl’s Nissan is one of them. Anthony has a Mazda Miata, which according to Karl, is not the best drift car. “You can drift a Miata,” Karl said. “It kind of sucks.” Anthony’s response: “No, it doesn’t.” Let it be known Karl’s first car was a Miata.

Illustration by Sam Smith.

The car itself lies on a smaller frame, the distance between wheels is about 89 inches, and it has only 90 horsepower. It is possible to drift, and some (Anthony) might say it takes more skill to do so. However, his Miata currently sits atop four wooden blocks, as it has no tires.

“It’s more of a square shape, so what that means is the rear end of the car, when it flicks out, it’s gonna wanna flick the other way faster because it’s got less length and throw to it.” Anthony explained to me, although I’m not sure I could truly understand unless I was behind the wheel.

His car reminds me of the ocean, not only because of the color, but also because it’s what I’ve always imagined myself driving down an Italian beach at sunset. But Mazdas are, in fact, Japanese cars, and in this case they’re here to drift and speed past people on the highway.

That’s because the streeting is heavily based in the original Japanese culture and style. Japanese drift cars—like Karl’s— can’t be imported to the US until 25 years after their original production due to US safety standards, but that doesn’t stop people from driving into the US with their banned cars and racing them on our tracks. .

But Katerina, a car enthusiast, informed me that there’s a price to pay for the talent and work put in to maintaining these cars. Drifting seems so secretive to the general public, and that’s because it is. Those who own nice cars have a deep fear of being stolen from. It’s not uncommon for jealousy to arise when dealing with expensive car parts.

“It’s so much cooler if you can drive and your car looks really cool while you do it,” said Katerina. “It’s about the money; you want to work hard, you want to put the money into your car, you want to be like, ‘I worked hard to have this,’ not, ‘I just picked up a piece of s—t car just cause I can drive.’”

Although the drive to keep culture alive is strong, there’s a strange hatred toward those who copy the look of another driver’s car. It seems contradictory, especially when so many within the community have the same heart shaped sticker on their windows. (Never the body, don’t want to ruin the paint!)

GIF by Sam Smith.

There is, however, a rift within the subcommunity. If you’re not in the sweet spot with the right car and skills, you’re an outsider. On one hand, there are those who have the money to buy the cars, but lack the skills needed to drift. On the other hand, there are those who can drive but don’t get the recognition because their car doesn’t meet standards.

“It’s so much cooler if you can drive and your car looks really cool while you do it,” said Katerina, a car enthusiast. “It’s about the money; you want to work hard, you want to put the money into your car, you want to be like, ‘I worked hard to have this,’ not, ‘I just picked up a piece of s—t car just cause I can drive.’”

Those standards are heavily based in the original Japanese culture and style. Oddly enough, Japanese drift cars—like Silvia’s— can’t be imported to the US until 25 years after their original production due to US safety standards, but that doesn’t stop people from driving into the US with their banned cars and racing them on our tracks.

Drift culture, while divisive, is pumping blood to the hearts of every wide-eyed, hand-gripped and mind-focused drifter out there.

Editor’s note: middle names were used in this article to protect subjects’ identities and privacy.

Header by Sam Smith and Cody Corrall.

Our Favorite Stories From 2018 – Fourteen East

4 January

[…] also did a lot of writing. In 2018, we published over 170 stories with topics ranging from features on Chicago’s drifting community to the rising health concerns of e-cigarette use among young adults. We started our investigation […]