She was a high school valedictorian who had to turn down a full ride, he worked full time but couldn’t afford community college and another’s family couldn’t afford a year of tuition, despite putting up $80,000.

While these stories are familiar to many families in the United States, there is one thing that separates the above accounts from the rest — documentation.

Because these three Illinois residents — Maria Valenzuela, Samuel Gonzalez Jimenez and Yesenia Garcia — came to the U.S. as minors, they do not have social security numbers. This makes them ineligible for financial aid assistance available to other college-bound students, such as grants, loans and public scholarships. Any assistance they could hope to receive has to come from the state level.

But after Wednesday, things could change for undocumented students in Illinois. Nearly a month after it passed in the house with a 66-47 vote, HB 2691 was passed in the Senate with a 35-15 vote. The bill now heads to Governor Pritzker’s desk, who has until July 7th to sign or veto it.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, Illinois is one of 18 states that allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition rates. Soon, these undocumented students may be able to apply for FAFSA to help cushion the blow of increasingly high tuition cost at the state’s public and private universities.

The Illinois Coalition of Immigrant and Refugee Rights last tried passing similar legislation to give undocumented students access to financial aid in 2015.

That bill, in contrast to HB 2691, didn’t even get called for a vote, but it did make the agency reconsider what they needed to change to move forward.

The new bill, introduced by State Rep. Elizabeth Hernandez in February, claims to be more inclusive than their previous attempts by benefiting more marginalized communities. It would provide financial assistance via an expansion of MAP grants to transgender students, undocumented students and students who are stuck taking a significant amount of remedial classes in college. The bill does this all by creating the Retention in Illinois Students and Equity act, or RISE act.

ICIRR says that because most students go to public schools, the quality of their education depends on their zip code. Zip codes with lower funding generally create public schools with lower quality education. Schools with lower quality education struggle to prepare their students sufficiently for college and many end up taking remedial classes to catch up. Because there is a 75-credit cap for MAP grants, the RISE act would also allow students to keep receiving more money if they are not yet a junior at their institution.

$9 million is expected to be distributed through MAP grants to approximately 3,500 possible students. ICIRR explains the RISE act is flexible enough for an expansion of students and funding.

If Governor Pritzker signs the bill into law, four of the five most populous states in the country would give undocumented students the opportunity to apply for financial aid. However, even if Illinois was added to the list, the number of states offering something similar would sit at only seven.

Three states, Arizona, Georgia and Indiana, have outright prohibited in-state tuition rates for undocumented students. Alabama and South Carolina have taken it a step further, barring undocumented students from enrolling at any public postsecondary institutions.

Tanya Cabrera, a task member of the RISE act, said it was important that it pass because “it would be a win in this administration, a win that gives hope that the fight is still going on” for equity in education.

On the front lines of that fight for education equity is Jimenez, whose mother left him to be raised by his grandmother in Mexico City when he was one year old. Jimenez said she left with the intention of providing for them from them “a better life” by working in the U.S.

“She left to make money, finish paying off the house, and build rooms to provide her kids a better future,” Jimenez said.

But as time went on, she saw news of rising insecurity, robberies, assaults and drugs that were spreading close to their city. His mother saw that her hometown was not a safe place for her son to be by himself.

Jimenez had been a victim of armed robbery three times in broad daylight in the streets of Mexico City. He was just 15 years old the first time it happened.

“A man on a bike flashed a gun on me,” Jimenez said. “The second time, a person came up to me near the Roma neighborhood with a knife. He took my phone and wallet.”

“The third time was tricky. Someone got behind me and demanded for my wallet. He had a gun or something. I didn’t turn around to see.”

For Jimenez, the decision to go to the U.S. was a heavy one. His mother said she wanted to give him “an option of life where he could accomplish anything, if he wanted it enough.”

At 17, Jimenez chose that option and crossed the Rio Grande illegally on an inflatable tire with a group of three men and three women. His mother paid $25,000 for guides that would take him from Mexico City to Vernon Hills, Illinois.

“It was suspenseful because you didn’t know if the police would arrive,” Jimenez said. “Everything was dark, they told us to take our clothes off to cross the river because they couldn’t be wet. When we got to the other side we had to step out and into the water and the dirt. And the mosquitos were also a bother.”

Once arriving in Vernon Hills, Illinois, Jimenez recalled wanting to continue his education by graduating high school and then going to college. But the first thing he did was work as a dishwasher at a restaurant his older brother had been employed at. Knowing that it cost his mother and family so much to have him over here in the first place, he gladly pitched in for the rent, water and electricity.

Jimenez and his brothers also take turns sending money to their retired grandma still living in Mexico City every other payday.

After a couple months, Jimenez was able to enroll at Stevenson High School for his senior year. He paid the enrollment fee, and was able to go to school five days while continuing to work full time.

When it was close to his graduation, Jimenez said he “didn’t think it was possible to go to college because of the expenses.” His counselors however, were able to recommend him to community college where tuition would be more affordable. He enrolled at College of Lake County to study education. His goal at the time was to help students who were learning English as a second language — just as he did when he was in high school.

Paying the first semester out of pocket and providing for his family proved to be financially impossible for Jimenez. Because he still had the same expenses he did in high school, he couldn’t enroll for the spring semester.

Jimenez now works full time as a manager-in-training at the same restaurant, but he still wants to go back to school.

“I would go into business, I enjoy working at the restaurant business,” Jimenez said. “I want to work at a bigger business and at a bigger restaurant.”

Dr. Bernadette Sanchez, a professor and community psychologist at DePaul, would describe a student like Jimenez as a “stop-and-go student” because he enrolled in the fall, but stopped in the spring.

Dr. Sanchez, who completed a study on Latinx students transitioning from high school to college, witnessed a similar trend for undocumented students she observed.

“Typically, undocumented students go to community college because it is cheaper and they pay out of pocket because they don’t qualify for financial aid,” Dr. Sanchez said. “They couldn’t enroll in the spring because they still owed money for the fall.”

In that time, people like Jimenez often work to finish paying the original tuition bill and enroll in the next semester that’s available for them — whether it be spring, summer or fall — a “stop-and-go” student.

“Undocumented [residents] see education as an opportunity to further themselves,” Dr. Sanchez said. “They are also hopeful that with a college degree they will have more options (for employment) and that things will change in the U.S. and be able to work in the U.S. legally.”

Jimenez had to support his family, but Valenzuela was fortunate enough to have family that could support her. Even so, Valenzuela would have to face challenges that Jimenez was able to avoid. That’s because Jimenez knew he was undocumented — and Valenzuela didn’t.

While applying to colleges her junior year, she asked her father what her social was. Valenzuela recalls her father saying “Oh m’ija, you don’t have one…you don’t have papers.”

“So then I understood…I don’t have papers…I’m undocumented. Got it,” Valenzuela said.

Now 22, Valenzuela has resided in Chicago since she was five. Before immigrating to the U.S., she lived with her family in Nogales, Sonora, a border town in Northern Mexico. The family fled, like many from Mexico and Central America, like many from Mexico and Central America, due to safety reasons. They came here on plane with a tourist visa they would eventually overstay. Valenzuela said that because she was so young, she thought “undocumented meant I couldn’t visit home again”.

Valenzuela graduated high school and enrolled at New York University with a financial aid scholarship of $24,000.

However, she explains that “it was nothing in terms of genuine financial support.”

“Because of my status, my family paid over $80,000 that year, and I am still in debt to this day,” Valenzuela said. “My dad was able to make payments at the very last minute,” she said.

Valenzuela said her family paid late fees, even if they were only late by a few hours.

Because Valenzuela is a DACA recipient, she could apply for DACA with advance parole to immigrate legally for a study abroad trip to Argentina. She said that the coordinators only gave her a list of resources that would help her find a lawyer. Valenzuela says instead of helping her with the paperwork in a positive way, it was “stop, you need to get a lawyer.”

Valenzuela knew she could legally travel with advance parole because it was an educational experience.

“To see them not pursue it was the biggest realization for me that [NYU] had obviously no support system for me.”

Valenzuela then enrolled as a part-time student at DePaul her sophomore year. She was able enroll full-time after getting a couple more scholarships, including the OMSS Scholar Award and the Monarch Scholarship for undocumented students. With tuition being fully covered at DePaul, Valenzuela is set to graduate this spring.

Public colleges are generally more affordable than private ones. But because public colleges have more public scholarships, it still might not be enough for undocumented students to enroll at them. The advantage of private scholarships is that anyone can apply for them. Because the OMSS Scholar Award and the Monarch Scholarship are private scholarships at DePaul, Valenzuela was eligible to apply and ultimately receive them.

Garcia, similar to Valenzuela, came to the U.S. when she was very young. Garcia’s mother and brothers lived with her in Guanajuato, Mexico. Her brothers, who were in their late teens, had migrated to the U.S. to send money back home, like Jimenez does, to help provide for the family. She says her brothers did this because times were tough.

“We were living in poverty…my father was in and out of the picture, my mom was a house mom,” said Garcia

Garcia said she was the translator for her mom, back when they weren’t so available. She says sometimes it was simple, like a parent teacher conference. Other times it was more difficult, if it was something that might involve a doctor.

”When I was six, I was translating technical terms and medical terms,” Garcia said. “I didn’t know what it was — let alone how to translate it into Spanish.”

Garcia did well in middle school and graduated valedictorian of Bloom High School. But that’s when the real problems started to set in for her. Because she was undocumented, she was not able to claim the full-ride scholarship she was offered at Purdue University in Indiana. Because Purdue is a public university, they could not give her the scholarship.

Garcia then went on to community college while working full-time to pay for tuition. She would graduate with an associates degree then continue her education at St. Xaviers University. After much hard work, she graduated with a bachelor’s’ degree in psychology.

Garcia recalls attending St. Xaviers was a difficult time for her trying to get enough sleep because she worked graveyard shifts at a currency exchange shop.

“One day out of the week I would go straight to school after work,” Garcia said. “I would start at 10 p.m. and get out at 6 a.m. and drive straight to school because I had a class at 9 a.m. Those days I would just sleep in my car in the parking lot.”

Garcia is now a part of the fully-funded PhD Psychology program at DePaul. Now a graduate student, her tuition has been waived, and because of the demanding program she is involved in, she receives a stipend that is intended to cover her expenses.

“It’s like a paycheck,” she says.

Because of these obstacles, it might not sound far-fetched that for undocumented students, only five to 10 percent of them pursue a college degree, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Since undocumented students can apply for private scholarships, private grants and private colleges across all 50 states, the dream is a long shot but ultimately achievable. Education is a big risk for them, but that doesn’t stop them from trying.

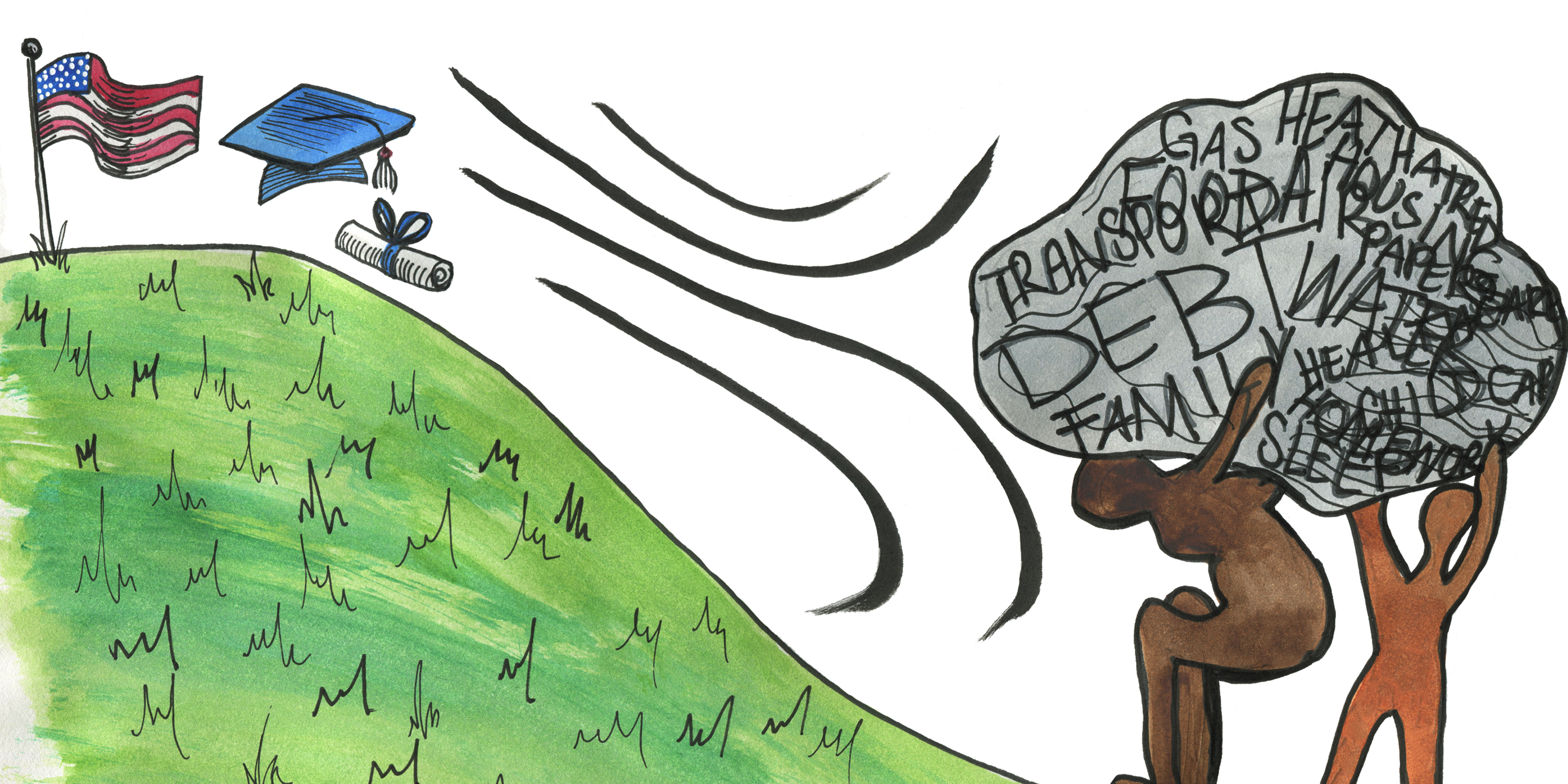

Header illustration by Jenni Holtz, 14 East.

NO COMMENT