Fifty years ago this month, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in Oakland, California. This piece considers the organization’s legacy by examining the lens through which most Americans would have first experienced the Panthers: the news media.

On May 3, 1967, a story appeared in the New York Times: “ARMED NEGROES PROTEST GUN BILL.” It was a little over 500 words long, tucked away on page 24.

In California the day before, it had been beautiful — not unusual for Sacramento, sure, but that didn’t make it unpleasant. A light breeze floated over the lawn of the Capitol building. The scene, complete with a rustle of leaves, some birdsong, and a distant siren, was punctuated by the sound of car doors slamming from across the street.

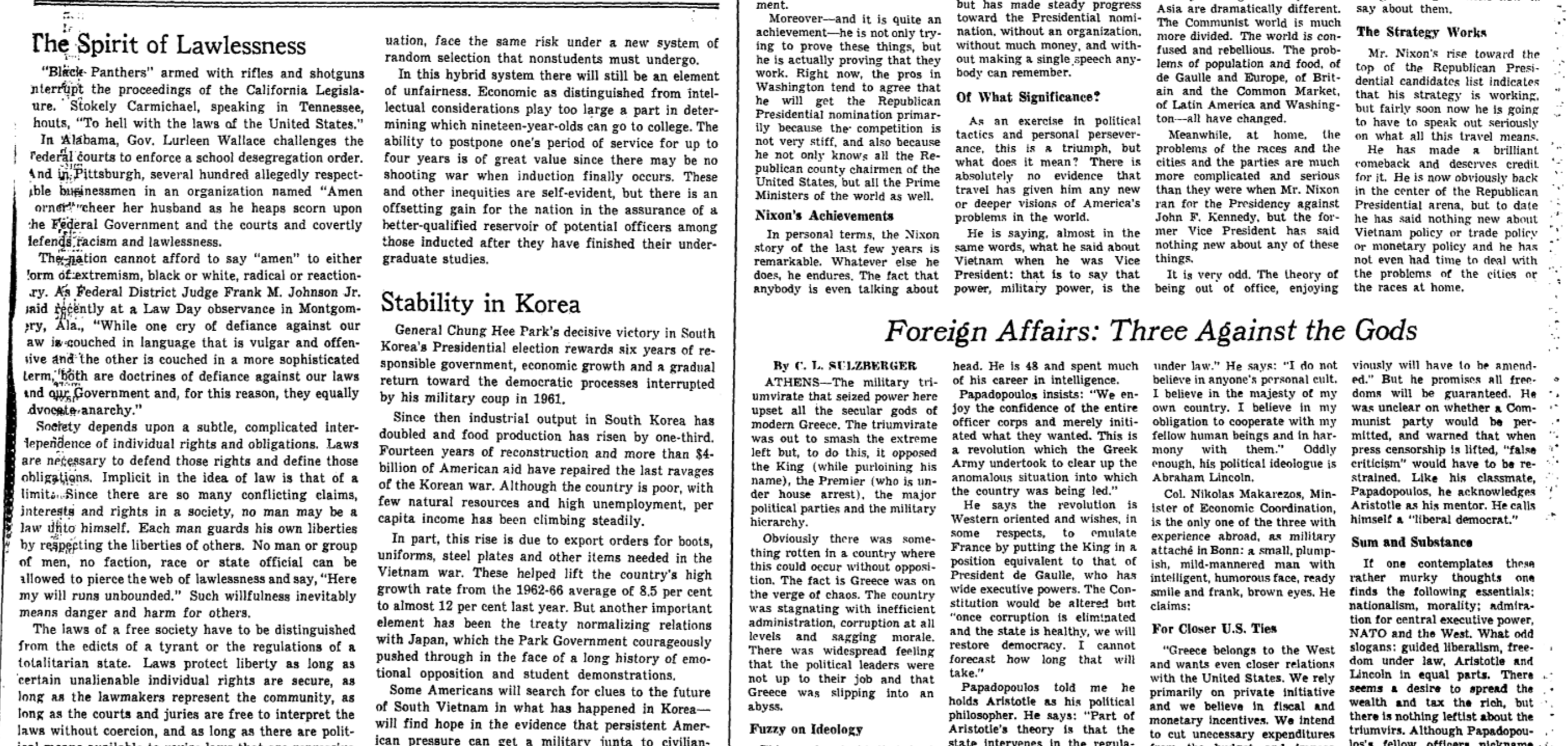

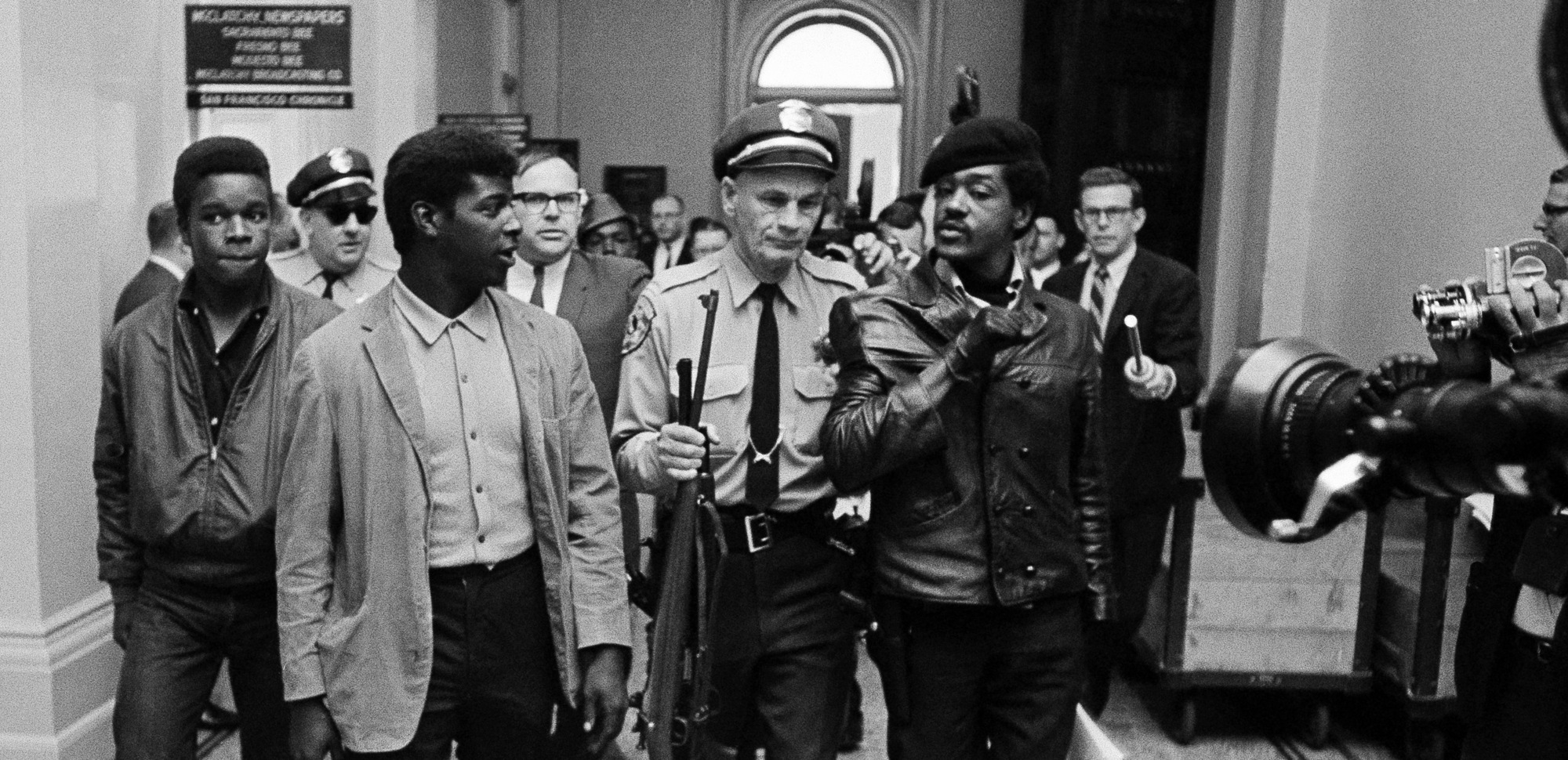

Minutes later, a few dozen black activists walked into the middle of the California State Legislature to protest the Mulford Act — a gun control bill introduced by a Republican — with guns of their own. When they entered the Assembly chamber, hysterical legislators dove under their desks until the sergeant-at-arms had carefully confiscated the weapons.

Immediately, court reporters swarmed the men in leather jackets and black berets, shouting over one another while the protesters asked to speak to their legislators. One activist read a statement condemning the disarmament of black citizens while the press corps asked who they were, what they were doing, exactly. The Black Panther Party was about to make its national debut.

Whenever the press is tasked with explaining something unprecedented to the rest of the world — anything from Sputnik to Ken Bone — they can get it wrong.

Fifty years later, the whole thing sounds almost impossible — like a late-season episode from an alternate history show. Take a moment to imagine the media apocalypse that would have followed today. Life as we know it would have been consumed by the tweetstorms, the helicopter fly-overs, the pundits melting over black militant terrorism.

But media meltdowns aren’t a recent phenomenon. Far from it. Whenever the press is tasked with explaining something unprecedented to the rest of the world — anything from Sputnik to Ken Bone — they can get it wrong. Its relationship with the Black Panther Party can be understood as a case study of media framing: how initial encounters and racial awareness can define a movement, as well as change the trajectory of the movement itself.

Despite the well-publicized strides of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, racism didn’t exactly feel like it had left the building by 1966. Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Voting Rights Act was followed days later by the Watts Rebellion in California; Los Angeles roiled and burned for almost six straight days, fueled by allegations of roadside police brutality against a black motorist.

To some, the urban riots that followed Watts suggested that the era of progress by civil disobedience was over. Malcolm X — famously at odds with Martin Luther King — rejected the idea that America would ever be purged of racism through peaceful protest or legislation; white supremacy could never be destroyed using the “maker’s tools,” to borrow from Audre Lorde. Instead, X insisted that black communities “in areas where the government is either unable or unwilling to protect the lives and property of our people, that our people are within their rights to protect themselves by whatever means necessary.”

On Oct. 15, 1966, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California. As the name would suggest, members fought oppression through the armed protection of minority groups that they believed were being victimized by police brutality. Panthers drew local attention by driving through their neighborhoods, firearms displayed openly while they policed the police. “Copwatching” was uncomfortable enough for California to repeal their open carry laws via the Mulford Act, which did pass despite the Panthers’ dramatic objection.

The original six members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense from 1966 (Wikipedia)

Describing the Black Panther Party in a succinct way is difficult. The left tends to describe them as martyrs, the right as terrorists. They were a black, nationalist, revolutionary and eventually Marxist political party. They were relatively small in number, with only 2,000 registered members across the country at the organization’s height in 1969. They were not anti-white; while other black power organizations, such as the Nation of Islam, rejected the help of white progressives, the early Panthers welcomed “allies” who recognized their privilege and other racist structures. Contrary to popular perception both then and now, no part of the Panther platform advocated for racial separatism. Bobby Seale famously wrote that “we do not fight racism with racism. We fight racism with solidarity.”

But what many people remember about the Panthers isn’t some fuzzy notion of solidarity; it’s the violence. Rhetorical and otherwise, the Black Panther Party has defined itself by the violence it called for, employed and experienced. Panther leader Huey Newton was convicted of manslaughter in a shootout that killed Oakland P.D. Officer John Frey in 1967 (though the trial was eventually thrown out on appeal). Bobby Hutton was killed by Oakland police during what some Panthers later admitted to being an ambush in 1968. In 1969, Panther leader Fred Hampton was assassinated during an FBI raid in Chicago.

And those are just the ones that made national news.

Outside these instances of direct involvement, it’s impossible to quantify the impact that the organization’s rhetoric — such as the motto “the only good pig is a dead pig” — had on broader crime trends. However, in a congressional hearing with a former editor of the Black Panther newspaper in 1970, U.S. Rep. L. Richardson Preyer tried when he opened with this:

During the 10-year period, 1960–1969, there were 561 law enforcement officers feloniously murdered while protecting life and property. In 1969, the last year for which complete statistics are available, there were 35,202 assaults on police officers, 11,949 resulting in injury. Eighty-six police officers, a 34-percent increase over 1968, were killed. While there are no complete statistics for 1970, the trend, if anything, would appear to be increasing.

Then, he cited the source of the idea that the increasing violence against police officers was from Panther rhetoric:

News accounts have alleged that certain types of these killings and assaults have resulted from Panther activities. Statements by Panther leaders and remarks in their newspaper would seem to leave little doubt that the Panthers attempt to encourage physical attacks on police.

If we assume that Preyer speaks for the mainstream American conscious, this implication of mass media raises a certain dilemma. If the Panthers were damned by the media’s coverage, why would they seek it out? And if the media was opposed to Panthers’ message, why would they cover it at all?

Exposure is critical to the success of any social movement. For the Panthers, national ambitions required national press. The best way to find that exposure in the 1960s was through the news. It could be a local morning radio show or a senator’s op-ed in the Wall Street Journal — the aim was the same.

Sidney Tarrow, a political theorist at Cornell University and author of Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action, and Politics, writes that much of the struggle in activism is the tug-and-pull of competing frames. “While movement organizers actively engage in framing work,” he said, “not all framing takes place under the auspices of control… they compete with the framing that goes on in the media, which transmit messages that movements must attempt to shape and influence.”

In other words, the art of publicity is a sort of cycle: activists put out their message in the hopes that the media will pick it up, the media decides if and how to report that message, and the activists have to adjust their frame accordingly.

The editorial board of the New York Times condemns Black Panthers’ protest at the Sacramento legislature (May 7, 1967)

Bobby Seale and Huey Newton had seen what happened to a movement when the press lost interest. Ten years before the Party was founded, desegregation activists in the South tried and failed to capitalize on Brown v. Board of Education. Writing on the decision’s fallout, Harvard professor Michael Klarman noted that one of the reasons desegregation took so long to take hold was a lack of public awareness. “Media attention quickly waned,” he said, “and demonstrators usually failed to accomplish their objectives.” Klarman then pointed to the more bloody incidents of the Civil Rights Movement; the media started to pay attention when the backlash against black protesters became violent, and only then did public opinion begin to shift.

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson assembled the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders to study the race riots of his presidency. A year later, it released its final report with an answer as to why the unrest took the news media by surprise with a shocking frankness; “The media report and write from the standpoint of a white man’s world,” the commission declared, and “fewer than 5 percent of the people employed by the news business in editorial jobs in the United States today are Negroes.” Johnson ignored the report and rejected its recommendations.

The question, then, is how the media — an almost entirely white, elite-educated workforce lead by white, elite-educated men — navigated and presented the country’s first quasi-mainstream black power group. Was the coverage fair? No, the Panthers were not perfect and yes, some members encouraged and committed felony crime. Despite that, the themes and ideals they espoused 50 years ago carry a certain element of timelessness — particularly as they’re echoed by activists with the Black Lives Matter movement today. The Panthers pushed police brutality into the national dialogue long before you could find it on YouTube.

Print news has always been one of the most foundational parts of modern journalism, supplying a huge share of the information broadcast by all other forms of media. According to a Pew Research study on Baltimore’s “news ecosystem” from 2010, 61 percent of all stories containing new information originated from a print source. Take one step back; because only 17 percent of the stories examined by Pew in the study had new information at all, the 10 percent of news that print stories came up with accounted for 50 percent of all the information that circulated in Baltimore.

Second, print journalism also constitutes a significant amount of academic influence. In a 2007 paper, Rima Wilkes and Danielle Ricard argued that elite print media, such as the New York Times, often set a media narrative for the rest of the country. Starting in the 1970s, academics increasingly turned to newspapers as a reliable source of the information. Just as historians would begin to analyze the Black Panthers, newspaper accounts would be more than happy to give their side of the story.

I’ve left a condensed version of my story’s lede from the top of the article below. Give it a skim.

Minutes later, a few dozen black activists walked into the middle of the California State Legislature to protest the Mulford Act with guns of their own. One protester read a statement condemning the disarmament of black citizens while the press corps asked who they were, what they were doing, exactly.

You may notice on your second go-around that the language is somewhat diplomatic. Activists walked into the building, entered the chamber, asked to speak to their legislators and got their picture taken. I could replace “activists” with “Girl Scout Troop 191” and you’d have a lovely field trip.

The Sacramento Bee’s front page story the day after the Panthers protest of the Mulford Act. (Sacramento Bee 1967)

Were the reporters of yesterday so reserved? Not exactly.

On May 3, 1967, the front page of the Sacramento Bee screamed: “CAPITOL IS INVADED.” Publications across the county — from the New York Times to the Pocono Record in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania — ran one of a few different stories from wire services. One passage from the Associated Press account read:

It was one of the most amazing incidents in legislative history — a tumultuous, traveling mass of grim-faced, silent young men armed with guns roaming the Capitol surrounded by reporters, television cameramen, stunned police and watched by incredulous groups of visiting school children.

Let’s break that down. The focus here is a “traveling mass of grim-faced, silent young men armed with guns.” That description is misleading, if not wrong; of the 30 protesters that showed up at the Capitol that day, six of them were women. Furthermore, why do we care that they were silent or grim-faced? The imagery is strangely cold for an “amazing” incident. And silent? Wasn’t a statement read? Or could the protesters not be heard over media’s frenzy inside the assembly chamber?

And in this account, the Black Panthers didn’t walk around the Capitol; they roamed it. That word doesn’t just carry the implication of aimlessness, but of an inherent danger. Tigers roam the jungle. Vagabonds and vandals roam the streets. The Black Panthers roamed state grounds not with a purpose, but a menace.

What drives the AP’s coverage is the specter of violence. In the passage above, young black men with guns are juxtaposed against shocked police and a bunch of school children.

The AP’s lede is more direct:

SACRAMENTO — A band of young Negroes armed with loaded rifles, pistols and shotguns entered the Capitol Tuesday and barged into the assembly chamber during a debate.

From the first sentence, we know this story will not be about the content of the protest, but the method. These were black men with loaded weapons (“rifles, pistols, and shotguns” all listed for full effect) who barged into the room. The undercurrent of fear is inescapable, even as the story eventually notes that “during the whole incident there was no real violence, and no shooting occurred.”

It would be unfair to label the story’s author as an out-and-out racist. Jane Rhodes, a professor of African-American Studies at the University of Illinois-Chicago and author of several books examining the relationship between black Americans and the press, argued in 1999 that the Black Panthers “were invested in the fear frame that they helped to shape.” She quoted Bobby Seale’s reflection of the Sacramento invasion from 1970: that they fully intended to “use the mass media as a means of conveying the message to the American people and to the black people in particular.”

“Many, many cameramen were there,” Seale continued. “Many, many people had covered this event of black people walking into the Capitol, and registering their grievance with a particular statement.”

In other words, the AP’s spin can’t entirely be blamed for being influenced by fear when that fear was intended. What was problematic, however, was how fully they bought into the frame and prioritized it in the story. Furthermore, the AP’s story had an outsized impact; first, by virtue of being a wire story, it was disseminated to hundreds of papers throughout the country. Second, because it was writing about a topic that had never really been tackled nationally, it was introducing the frame that would eventually define much of the coverage that would follow the Black Panthers.

It wasn’t because every reporter from the 1960s was racist. Some would have been overtly prejudiced, while others would have held implicit racial bias by virtue of the era; it would have been difficult for anyone to remove themselves from that frame in a nation where “separate but equal” was enshrined as a constitutional principle. But even beyond that, the structural makeup of newsgathering — the basic nature of journalism — makes it vulnerable to the subtle prejudices of a just a few people.

“News bias” is an inescapable part of any pluralized society, particularly in a democracy that encourages public participation and the freedom of speech. By another name, it’s the Rashomon Effect. Named after a 1950s Japanese film that played with the viewpoints of different characters from a murder, this phenomenon describes the dilemma of perspective in reporting; for every event they cover, a journalist relies on their own experience and the accounts of other people. Are three interviews and a video recording enough to capture the reality of an event in writing?

The problem with having a national media, then, is that journalists are imperfect people dependent on other imperfect people to somehow ascertain the truth of an experience that they then present to a country of 300 million other imperfect people. A story that the New York Times runs — even as a “newspaper of record” — is the product of necessarily limited social interaction.

So that the Times or any other major media outlets would mischaracterize the Black Panthers at the onset, particularly given their spectacular opening number, isn’t surprising. It should almost be expected. Nonetheless, America’s decision-making elite relies disportionately on the media to construct their worldview, meaning that news accounts — however limited — have an outsized role in the trickle-down construction of public reality. Whatever implicit, unintentional racism sneaks into a story gets tucked away inside the news of the day, warts and all.

There’s also the dilemma of privately owned news organizations. Since the American government doesn’t fund media institutions on principle (First Amendment and all the jazz), the institutions rely on a commercialized newsgathering model to survive. That means that the events that get everyone’s attention or appeal to our baser instincts — a horrific accident or sex scandal, for example — are covered and prioritized, rather than the events that may be more important, like a round of budget cuts at City Hall. There’s no marketability to the mundane, while nothing sells papers like good ol’ fashioned conflict.

And the Black Panther Party offered no shortage of conflict. They talked about shooting the police, shot at police and were in turn shot by the police. It wasn’t all the Panthers killing police, nor was it all the police killing Panthers. But it was, in a word, a mess.

The FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover labeled Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country” in 1968, at which point they’d fallen into the crosshairs of the controversial (and often illegal) COINTELPRO program. Disbanded after it was revealed to the public in 1971, COINTELPRO was a domestic surveillance branch of the FBI eventually condemned by a Senate investigation known as the Church Committee. In their final report, they declared that while “many of the techniques used would be intolerable in a democratic society even if all of the targets had been involved in violent activity, COINTELPRO went far beyond that.”

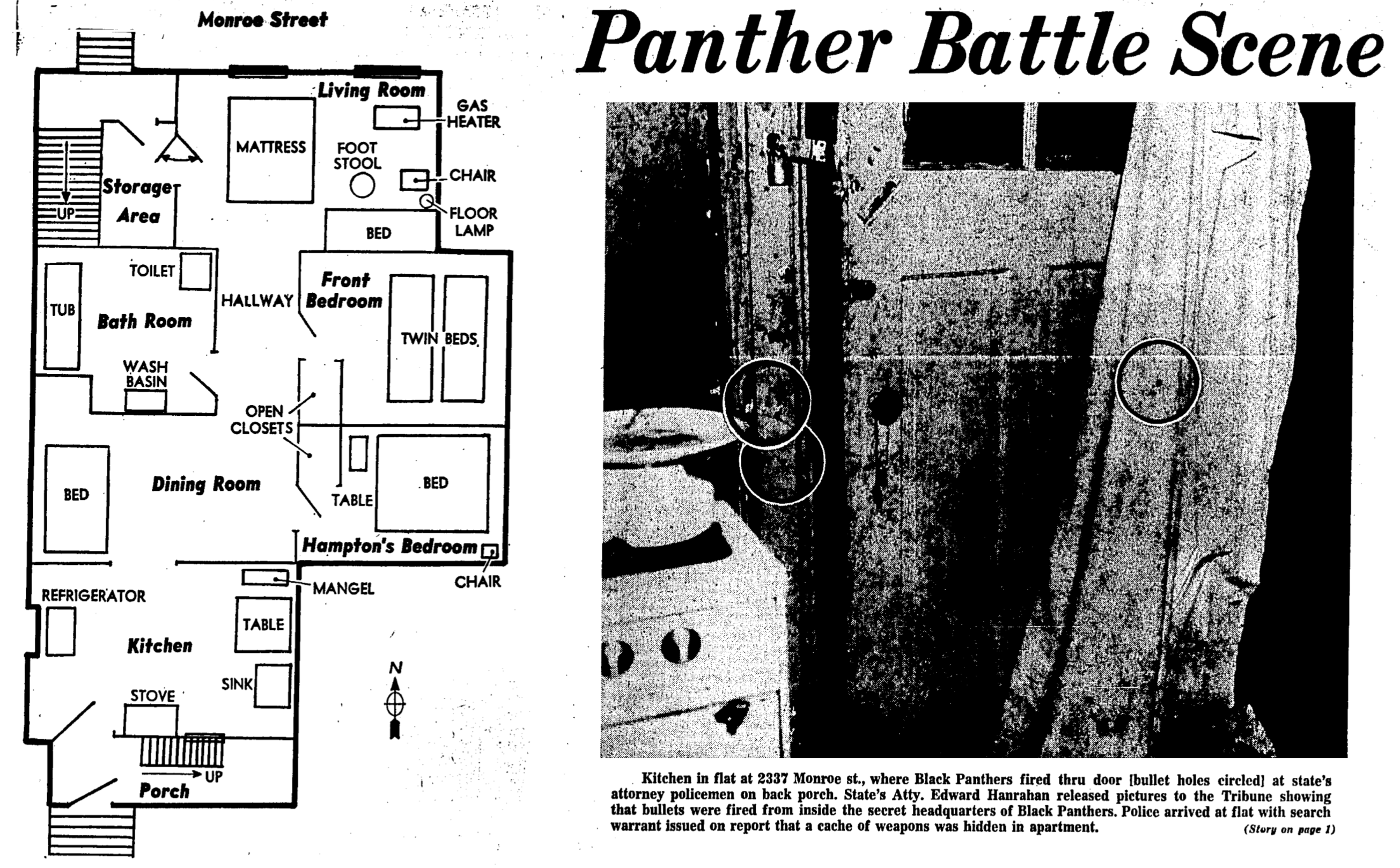

The Church Committee specifically condemned its “Black Nationalist” classification, which was so broad that it labeled the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (the one led by Martin Luther King) as a hate group. The FBI conspired with police departments in San Diego, Los Angeles, Oakland, and even Chicago to raid Black Panther headquarters, rarely with evidence of wrongdoing (nevermind a warrant). This resulted in the killing of several Panthers, perhaps most notably in December 1969 with the assassination of Chicago leader Fred Hampton.

An “exclusive” police account of the shooting that killed Fred Hampton, published in the Chicago Tribune. The image above points to holes that supposedly showed that the Panthers shot first. They were later proven to be nail holes (Chicago Tribune, Dec. 11 1969).

But what gets lost in the headlines is that the Black Panther Party did more than clash with police — they revolutionized the way America fed its kids. Their “survival programs” improved the lives of thousands of black Americans in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s in ways that the government had proved unwilling to and, by 1969, the “Free Breakfast for Children” program was serving over 20,000 grade school students in 19 cities across the United States. This wasn’t simply unprecedented; according to the University of Georgia’s Nik Heynen, it was “imperative for the social reproduction of many inner-city communities and… both the model for, and impetus behind, all federally funded school breakfast programs currently in existence in the United States.” By 1975, the government had fully embraced free breakfast programs. At the cost of $3.3 billion in 2012, it’s one of America’s largest social welfare programs today.

But the fact that the Black Panthers did it first wasn’t news. It didn’t have the bounce that a shootout or police raid did, nor did most major media outlets have the racial awareness or makeup to have even noticed the significance of such a program in action.

Half a century later, the problem hasn’t gone away.

In its coverage of the Ferguson Riots during the summer of 2014, the New York Times at one point referred to Michael Brown — the unarmed black man shot and killed by police — as “no angel” when details about him emerged: he was suspected of shoplifting before he was shot, had marijuana in his system, and may have resisted arrest before shots were fired.

There is an implicit disregard for human life in the suggestion that Brown may have been less than an ideal martyr. Did any of those factors amount to a capital crime? Did they make an instance of excessive, deadly force less of an injustice?

Today’s Black Lives Matter movement forms a clear parallel to the Black Panthers. BLM defines itself as an “ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.” The environmental similarities are notable; from their inception, both groups aimed to subvert institutionalized white supremacy within the police and judicial system while simultaneously dealing with an overwhelmingly white media.

In the back of your mind, you may be tempted to think that it’s 2016! We couldn’t be that white! Not 1960s white! But you’d be wrong. Overall, the American newspaper industry has seen the number of black journalists decline in recent decades, falling from 5.4 percent to 4.8 percent between 2003 and 2013. Does “fewer than 5 percent” sound familiar? Good memory: It’s the same figure the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders warned the country about almost 50 years ago.

“Race relations — life in black communities, even in Chicago with its incredible racial inequality and racial violence — it gets episodic coverage. It gets coverage when there’s an incident, but there’s not a lot of sustained beats.”

Jane Rhodes, now a department head and professor of African-American studies at the University of Illinois-Chicago, actually started out as a journalist in the 1980s. She taught journalism at Indiana University until 1996, when she left to teach ethnic studies in California, Minnesota, and eventually Illinois. Part of the reason she left journalism, she said in an interview, was the “real disconnect for many people of color and other unrepresented people between the kind of principles that journalism education argues — you know, the sort of pure objectivity — and the reality of life in these communities.”

According to Rhodes, much of black America doesn’t really see news media as a viable source of social change. It doesn’t have the track record.

“I think there’s a large swath of black Americans that see on a daily basis inequality in action, whether it’s the workplace, in schools, in neighborhoods, or whether it’s in political discourse,” she said, adding that “in general, race relations — life in black communities, even in Chicago with its incredible racial inequality and racial violence — it gets episodic coverage. It gets coverage when there’s an incident, but there’s not a lot of sustained beats.

“I think black Americans get frustrated by that.”

Then again, the differences in media landscape between 1967 and 2016 are stark. Consider, for a moment, the possibility that social movements no longer need the mainstream media just to survive. What if social media filled that gap, or filled part of it? Journalism as an institution has been rocked by the likes of Facebook, Twitter, WordPress and other outlets for journalism not done by card-carrying journalists.

This breach of the fourth estate has allowed prominent members of Black Lives Matter such as DeRay Mckesson or Alicia Garza to amass huge followings on Twitter; nearly 570,000 people follow Mckesson alone. For context, the Black Panther newspaper reached a circulation of 250,000 by 1969 — while impressive in its own right, the number pales in comparison to the reach of today’s nontraditional media.

Mckesson’s base might not sound like an awful lot compared to the New York Times’ 28.1 million followers, but he is a single citizen. Never in the history of humankind has someone been able to reach hundreds of thousands of people in an instant, free. The ubiquity of social media today — its ability to give a voice to the voiceless, no matter how small — highlights the degree to which the Black Panthers would have been dependent on traditional broadcast media 50 years ago.

In the end, both the national press and the Black Panthers succeeded and failed in their own way; while black power managed to enter the public consciousness for the first time, it really only attracted attention when it involved violence and was laced with extremism.

The landscape has shifted considerably between then and now; two days after the 50th anniversary of the Black Panthers, the International Association of Chiefs of Police issued a statement apologizing for the “historic mistreatment of communities of color” during their convention in San Diego. The organization represents 23,000 police officials across the country. On the other hand, you have the National Fraternal Order of Police, which dismissed the speech as “just words.” Last month, the FOP — which claims to represent 330,000 officers — endorsed Donald J. Trump for president of the United States.

Whose culture is decaying when a black performer expresses solidarity with the victims of police brutality?

Even so, the cultural memory of the Black Panthers retains the same undertow of racial animosity. While Coldplay (technically) headlined for Super Bowl 50’s halftime show, Beyoncé and Bruno Mars blew the performance out of the water; for the most-watched television event in the world, they gave a tribute to both Malcolm X and the 50th anniversary of Black Panther Party. Dressed in iconic black leather, berets, and at one point forming an “X” during “Formation,” the production shocked parts of the country. The following Monday, Rush Limbaugh took to the airwaves denouncing the show, describing it as “representative of the cultural decay and the political decay and the social rot that is befalling our country” and, with an unclear sense of irony, accused the artists of depicting “an entirely different country.”

One has to wonder who Limbaugh is speaking for. Whose culture is decaying when a black performer expresses solidarity with the victims of police brutality? Who exactly is he rallying when he invokes “our country?”

Black and white America are in fact very different places. Whether it’s the employment rate, mortality rate, incarceration rate, or in income, the differences could not be more stark. The news media has the unique ability to show these disparities, capable of reaching millions and framing the national dialogue every day. For almost 200 years, they have failed to do so. They will continue to fail so long as they speak from and for the white man’s world.

Header image: Associated Press (1967) Black Panther Party members were escorted out after they invaded the California State Capitol to protest the Mulford Act

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST