Allison Kupfer sat backstage at The Private Bank Theater in Chicago on Nov. 8, 2016. The cast and crew of “Hamilton” started the show in Chicago that night expecting to celebrate Hillary Clinton’s presidency after the performance. “Hamilton,” a celebration of contributions made by immigrants (namely one immigrant: Alexander Hamilton), is inherently political, but also patriotic in its mission to tell the story of our founding. On this particular evening, the stage was set for a political showdown in the PrivateBank Theatre, and across the nation. Kupfer, the show’s company management intern and a DePaul student, sat scrolling through her timeline on Twitter and refreshing the electoral map Google was updating in real-time, watching a sea of red wash over the United States of America. A deep pit of stress formed in her stomach.

“As the results started pouring in, people were just getting more and more devastated,” Kupfer said. What would happen? How would they come to work the next day? How would the show go on?

Allison Kupfer in “Hamilton’s” company management office (Al Amendola, 14 East Magazine)

New York City, a bastion of culture, once had a stronghold over the country’s theater scene. No more. Just in the past year Chicago has had Patti LuPone in “War Paint” at the Goodman, The Tribune’s Chris Jones’ evergreen editorial contributions, and now, “Hamilton.” Chicago’s identity is incomplete without talking theater.

According to “The National Trust Guide to Great Opera Houses in America,” the first theater in Chicago was opened in 1837 in an abandoned hotel dining room. The Chicago Theatre, originally housed in the Sauganash Hotel, moved venues the next spring.

Jane Addams’ Hull House, a settlement house for immigrants on the Near West Side, started a theater program in the 1890s which put on premieres of plays by the likes of John Galsworty, George Bernard Shaw, and Henrik Ibsen. This moment, when Chicago’s political scene joined forces with its theater market, helped begin a long tradition of activism through art in Chicago.

This tradition is continued today through spaces like Free Street Theater, one of the “first racially-integrated theater companies in Chicago,” the company’s website says, after its founding in 1969. The company creates “work that addresses pressing social issues from diverse points of view,” like the show “Dope” which they performed in 2014. Addressing marijuana use and America’s Prison Industrial Complex through performance, like “Dope” did, is no small feat, but Chicago has the experience and talent necessary to start dialogues about oppression.

It was during Chicago’s postwar stage renaissance where the city started to find its voice. Its players, The Goodman Theatre, The Second City, and Steppenwolf Theatre Company, created a dynamic new identity for the city to rival Los Angeles’ Hollywood glamour and the commercialism of New York theater. David Mamet’s 1974 “Sexual Perversity in Chicago” was his first success. The Second City has gone on to launch actors like Steve Carrell, Amy Poehler, Tina Fey and more to stardom. Chicago has been a longtime training ground for work that entertains, but also challenges people to think.

Decades later, we transport to New York. Enter Lin-Manuel Miranda, the man credited with bringing Broadway back from death’s door after the 2008 economic recession. The first line item to cross off on the American family budget was theater, and American theater was hit hard.

“In the Heights,” Miranda’s first show, premiered on Broadway in 2008. Nominated for the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, winning a Grammy Award for Best Musical Show Album, and winning four Tonys was an amazing success for Miranda’s show about the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York coming to terms with gentrification.

Urban folklore tells us that Miranda told Christopher Jackson (the original Benny in “In The Heights”) offstage one night that he was writing a show about Alexander Hamilton and wanted Jackson to play George Washington. After previewing music at The White House to the Obamas and finishing his writing at Hamilton’s residence in New York, Miranda was ready to show it to the world.

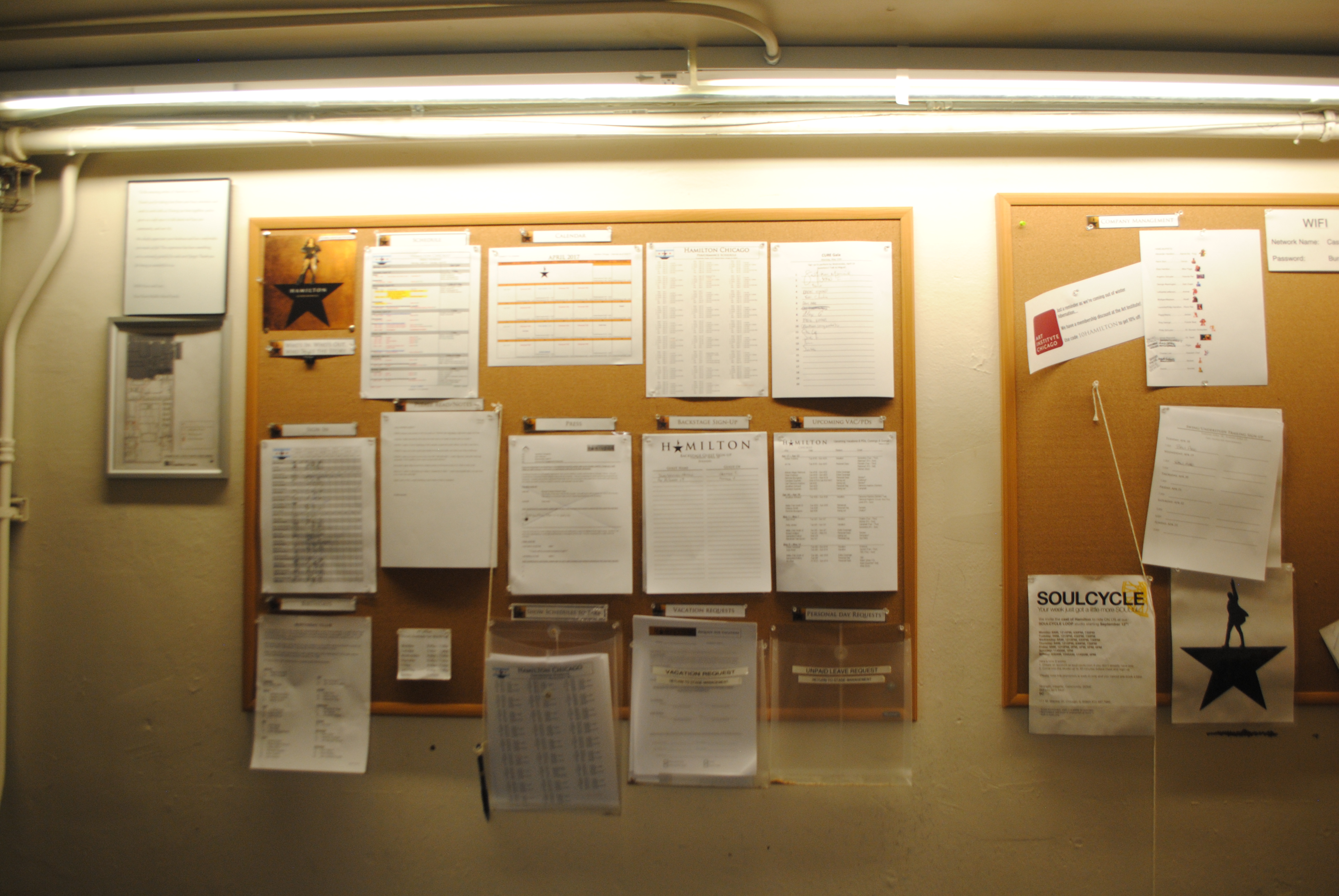

“Hamilton’s” call board at PrivateBank Theatre (Al Amendola, 14 East Magazine)

The show opened Off-Broadway at The Public Theater in New York in February 2015 and moved to Broadway at the Richard Rodgers Theatre in August of that year. According to Broadway World, “Hamilton’s” New York performances have been grossing more than $1 million a week since July 19. The show broke $2 million in a week in June 2016, and moved up to $3 million for the weeks of Christmas 2016 and New Year’s 2017. Then, “Hamilton” was rumored to be making its next play for another American city.

Chicago’s large market, theatrical tradition, media attention to theater and Broadway-like theater resources and spaces made Chicago the perfect fit for “Hamilton’s” second opening, according to Chris Jones.

Jones, the chief theater critic for The Chicago Tribune, said that New Yorkers see Chicago’s audience as “a close replication” of the audiences in New York, which serves as a sort of primer for other cities. “Shows that do well here usually do well in other cities.”

Jones also recognizes the similarities between Chicago and New York in “their willingness to engage with serious work.” In other American cities, theater is much more of an “escapist” tradition, he said.

Chris Jones at The Chicago Tribune (Al Amendola, 14 East Magazine)

“‘Hamilton’ has less competition here, that’s for sure,” Jones said. “New York is New York and Chicago will never be New York. But, what matters here is the work. People are not in it to make money, it’s not a bitchy world of competition. It’s a true community, a true artistic community.” Jones said he’s never left Chicago for New York because Chicago is “the most exciting theater city in the world.” If it’s 8 p.m. and Jones isn’t at the theater, he asks himself: “Where am I supposed to be tonight?”

Chicago’s The Theatre School at DePaul University ranked No. 17 in the country for acting by The Hollywood Reporter. DePaul has produced actors like John C. Reilly, Gillian Anderson and Judy Greer.

Playwright major Delia Van Praag is in her fourth year at The Theatre School. She grew up on Long Island in New York. Delia’s parents took her to shows ranging from professional Broadway to high school productions. Delia started participating in theater herself in ninth grade.

“I loved to perform, but it came to a point where I wouldn’t be marketable enough or good enough to be cast professionally, and that’s when I became more interested in the creation aspect,” Delia said.

“‘Next to Normal’ cracked my world open,” Delia said. When she was 16, she saw it for the first time on Broadway and would see it two times after. The show, about a woman with Bipolar Disorder, “changed the way” Delia thought. It shook her world up, and that’s what good theater does, according to Delia.

Delia Van Praag at The Theatre School at DePaul University (Al Amendola, 14 East Magazine)

Delia wasn’t sure if she was going to be able to go to college. With her crippling Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and anxiety, choosing a school was about more than just finding a fun place where she could learn.

“Anyone who’s been to New York knows it’s a magical city,” Delia said. “But I just felt like it was sensory overload all the time. When I came to Chicago, it felt so much more livable and calm.”

Delia admits that DePaul wasn’t initially on her list. She just got on Google one day researching theater schools.

“But, when I did my research, DePaul had one of the most established programs in the country, and it seemed like a perfect fit for me,” Delia said. “I feel like it’s so much accessible. Just like Chicago is a more livable city than New York, it’s also more ‘workable’ in regard to the theater scene. There’s less of a divide. In New York it’s: Broadway, off-Broadway, off-off-Broadway. Here there’s the big shows (Goodman, Chicago Shakespeare) but there are lots of small companies doing amazing work.

“Here, it’s a labor of love,” Delia said. “People aren’t doing it for the money, they’re getting by with second jobs and doing what they can to create and perform. It’s beautiful.”

Delia worked on a show with writer and DePaul student Jewells Santos called “The Deflowerment of Wendy Diaz,” focusing on the experience of a woman losing her virginity. “Jewells and I talked and we wanted to convey the experience of what it’s like to be young and how the pain that we inflict on ourselves and others inflict on us gets brushed to the side,” she said. “It’s painful and personal, but at the end it’s just another day. And I do think Chicago does a good job of showing how the personal is political. The private is political. Especially at a time like this.”

The tradition continues. In 2014, The Greenhouse Theater Center performed Holter’s “Hit The Wall,” focusing on the Stonewall Riots of 1969 that gave birth to the gay liberation movement. Chicago’s Annoyance Theatre put on “Good Morning Gitmo” in 2014, a play set on Sept. 11, 2039, at Guantanamo Bay. It staged a morning talk show hosted by the last remaining military personnel with detainee guests making paper airplanes out of documents their lawyers will never read.

“Gloria,” which was performed at The Theatre School at DePaul before making its way to the Goodman Theatre, is a show about mass shootings and gun violence. Chris Jones said in a review: “I’ve been worried of late that the theater in Chicago had lost its taste and capacity for risk — risk that must include forcing the culture business to confront its own complacency and growing love of groupthink. But ‘Gloria,’ which I could see heading to Broadway from here, is a great roar of truth-telling, keenly observed, self-critical and yet voiced with schadenfreude.”

“Gloria” is an example for how theater can spark a debate, and force the comfortable into action or, at the very least, active thought. “The show had no trigger warning,” Van Praag said. Delia hasn’t had personal experiences with gun violence, but she was shaking and crying at the end of the first act. But, Delia wondered, would it have the same effect if there was a trigger warning? She has mixed feelings about it. But, regardless, she’s thinking about gun violence weeks after the show premiered. Isn’t that what theater is supposed to do?

A “Hamilton” frenzy broke out in Chicago when the show was announced to be bringing a “separate resident” show (non-touring) to Chicago. Previews started on Sept. 27, 2016, and opened Oct. 19. The show sold out through March 21, 2017. More tickets have been added as extensions follow demand. Some of the cities that lost the battle have been added to the first U.S. Tour: San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, Seattle, Houston and Washington, D.C.

Chicago’s fight for “Hamilton” was not without precedent, either. “Wicked,” a smash Broadway musical prequel to “The Wizard of Oz,” was the first show to make a second home in Chicago, instead of just touring through. And clearly, they made the right decision bringing it here: the show ran from June 2005 to January 2009.

Broadway veterans joined the cast, including Karen Olivo, who starred as Vanessa in Miranda’s “In The Heights” in 2008 and as Anita in the “West Side Story” Broadway revival. Olivo left Broadway after “In The Heights” and moved to Madison, Wisconsin, to teach drama at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her triumphant return only added to “Hamilton” hysteria.

But perhaps it’s Hamilton’s political history that makes it uniquely fit for Chicago. The show, focusing on the founding fathers, is politically divisive today. A man began drunkenly shouting at the Chicago performance after the famous line “immigrants, we get the job done,” interrupting the performance, in December. He was arrested, pleaded guilty, and is now banned from the Loop’s Private Bank Theatre.

“Hamilton’s” casts have never been shied away from political activity either, sometimes making national headlines.

The Broadway cast of Hamilton, just earlier this month, donated their salaries from their Wednesday, March 8, evening performance to Dress for Success, “a charity that supports women in the workforce,” according to Gordon Cox’s Chicago Tribune article last week. Javier Muñoz, the show’s lead actor on Broadway, tweeted a copy of the program insert from that evening’s performance. It read:

Ladies and Gentlemen thank you for coming to the show. We would like to remind everyone that March is National’s Women’s History Month and today is International Women’s Day. In support of all women everywhere, a group of us at “Hamilton” have chosen to donate our salaries from tonight’s performance to Dress for Success, an international charity that supports women entering the work force. We thank all the women in this building for being here today and celebrating with us.

Vice President Pence attended the show in New York on Friday, Nov. 18, 2016. Following a performance marked with “boos” every time Pence stood or moved, the cast delivered a message at curtain call, just before the Vice President-elect could make his way out of the theater:

Thank you so much for joining us tonight. You know, we had a guest in the audience this evening. And Vice President-elect Pence, I see you’re walking out but I hope you will hear us just a few more moments. There’s nothing to boo here ladies and gentlemen. There’s nothing to boo here, we’re all here sharing a story of love.

We have a message for you, sir. We hope that you will hear us out. And I encourage everybody to pull out your phones and tweet and post because this message needs to be spread far and wide, OK?

Vice President-elect Pence, we welcome you and we truly thank you for joining us here at “Hamilton: An American Musical,” we really do. We, sir, we are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us — our planet, our children, our parents — or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights, sir. But we truly hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us. All of us.

Again, we truly thank you for sharing this show. This wonderful American story told by a diverse group of men [and] women of different colors, creeds, and orientations.

Vice President Pence told Chris Wallace that “it was a real joy to be there” and that the boos are “what freedom sounds like” during an appearance on “Fox News Sunday.”

President Donald Trump, in his signature style, responded early the next day with a series of tweets:

Our wonderful future V.P. Mike Pence was harassed last night at the theater by the cast of Hamilton, cameras blazing.This should not happen!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 19, 2016

The Theater must always be a safe and special place.The cast of Hamilton was very rude last night to a very good man, Mike Pence. Apologize!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 19, 2016

The notion that “The Theater” must “always be a safe and special place” is one that Delia has mixed feelings about. “I think that Donald Trump was asking for a safe and special place for Vice President Pence and his family, who feel safe everywhere because of their privilege and power,” Van Praag said. “So, I guess my question for him would be: ‘for who?’ The theater should be a safe and special place for people who can’t find comfort other places.”

On Nov. 9, 2016, everyone came to work the next day to piece together what happened the night before. “What the f*** happened?” and “How are we going to do this show now?” were the sentiments swirling around the theater that morning, Kupfer said.

The company gathered together on stage and just talked. Talked about what the future was going to look like for them as artists, as citizens. They decided to take all of their emotions and fuel the show with the excitement, disappointment, anxiety and uncertainty of the past 24 hours.

Allison Kupfer (Al Amendola, 14 East Magazine)

Kupfer says that the energy of the audience was “really down” as the cast waited for the show to start. “The cast walked onstage and it was one of the most electric performances I have ever seen them do. They were able to take all of the feelings they were feeling and put it into a show that directly correlates [to our political climate].”

That energy has carried on, Kupfer said. “The political climate isn’t becoming any less politically charged, and it’s made every performance [since the election] more powerful and more moving.”

Chris Jones said that he sometimes runs into Chicagoans who never attend the theater, but are still very proud of it. “People understand that we have something special and, over the years, I’ve always found that the work sustains me. Not all of the work is great, obviously, but there’s enough good work that I’m always anxious to get to the theater.”

“Hamilton” has broken out of the musical theater world and into the zeitgeist, incorporating conversations around identity, policy and entertainment. The show is politically charged only because of our country’s politicization of immigrant experiences and identities. There’s no grandiose statements about the state of our country today. The show is patriotic because of its in-depth look into an immigrant who changed the course of this country.

The show is a masterpiece, and one worthy of Chicago.

Header image courtesy of Al Amendola.

NO COMMENT