Day by day, night by night, students push and pull on the revolving doors as they maneuver their way through DePaul’s Student Center, built in 2000. Raunchy smells of soggy french fries linger atop the second floor, but the strong coffee beans on the main floor cover up the stench. Flowery architecture surrounds the building. Freshly paved concrete sits around the DePaul Student Center and the bronze-cast arms of Monsignor John Egan serve as a friendly welcoming symbol.

Students whistle in and out of the confines with heavy book bags and coffees in hand, while palms clutch phones. Caffeine and books scatter across tables.

Conversations regarding German idealism, American colonialism and Victorian morality fly throughout the air. Sorority leaders raise money, professors hold classes, and your hip clique smokes cigarette upon cigarette outside both the east entrance on Sheffield Avenue and west entrance on Kenmore Avenue. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll walk across a table of jocks pulverizing the DePaul basketball program.

The land in which that very Student Center was built once was a different gathering place. It was Alumni Hall — a place in which Mark Aguirre and Orlando Woolridge would meet up never to talk, but play. The sound of basketballs and loud cheers of fans would ring through the Lincoln Park block.

The corner of Sheffield and Belden was once a place where DePaul coach Ray Meyer would salute the likes of Adolph Rupp, Digger Phelps and Al McGuire. It was the very piece of land that was home to DePaul basketball from 1956 to 1980.

Clap by clap, win by win, DePaul put themselves on the national map.

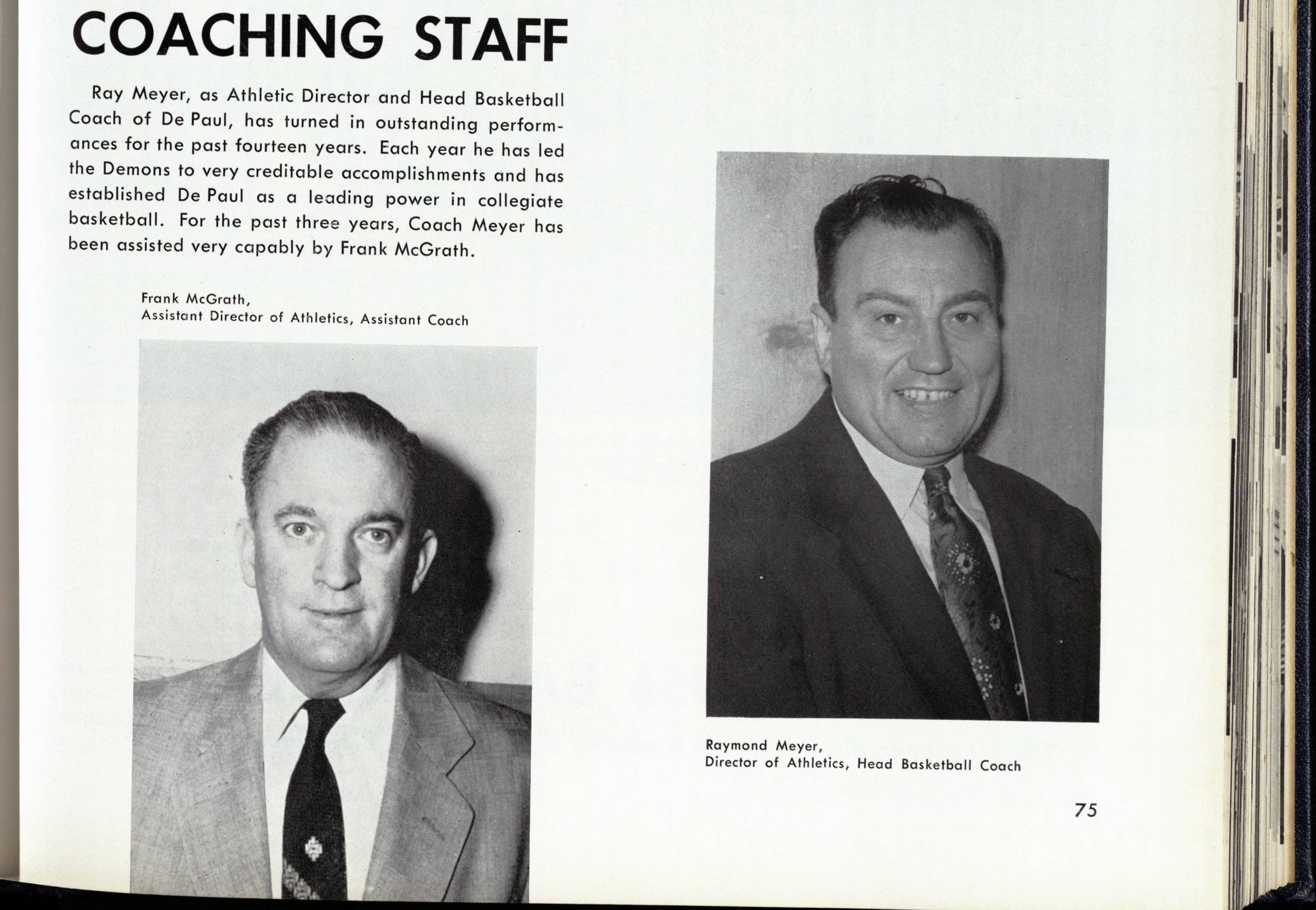

Frank McGrath (left) and Ray Meyer (right) in DePaul’s 1956 yearbook

After two Final Fours and nine Sweet Sixteen appearances, DePaul’s home court shifted thirty minutes west of Lincoln Park down I-90 to Rosemont’s 18,000-seat Allstate Arena. It was at Allstate Arena the program’s success continued as Ray Meyer coached his team to the number one regional seed three consecutive seasons in a row from 1980 to 1982.

DePaul’s program was that of pure excellence. Meyer had a staff and athletic department well-tooled. Their relationship with WGN served as a sort of personalized national broadcast, considering the WGN games were telecasted in most major markets. This served as a means of self-recruitment for the program, and their unprecedented success only made the program a bigger and better sell.

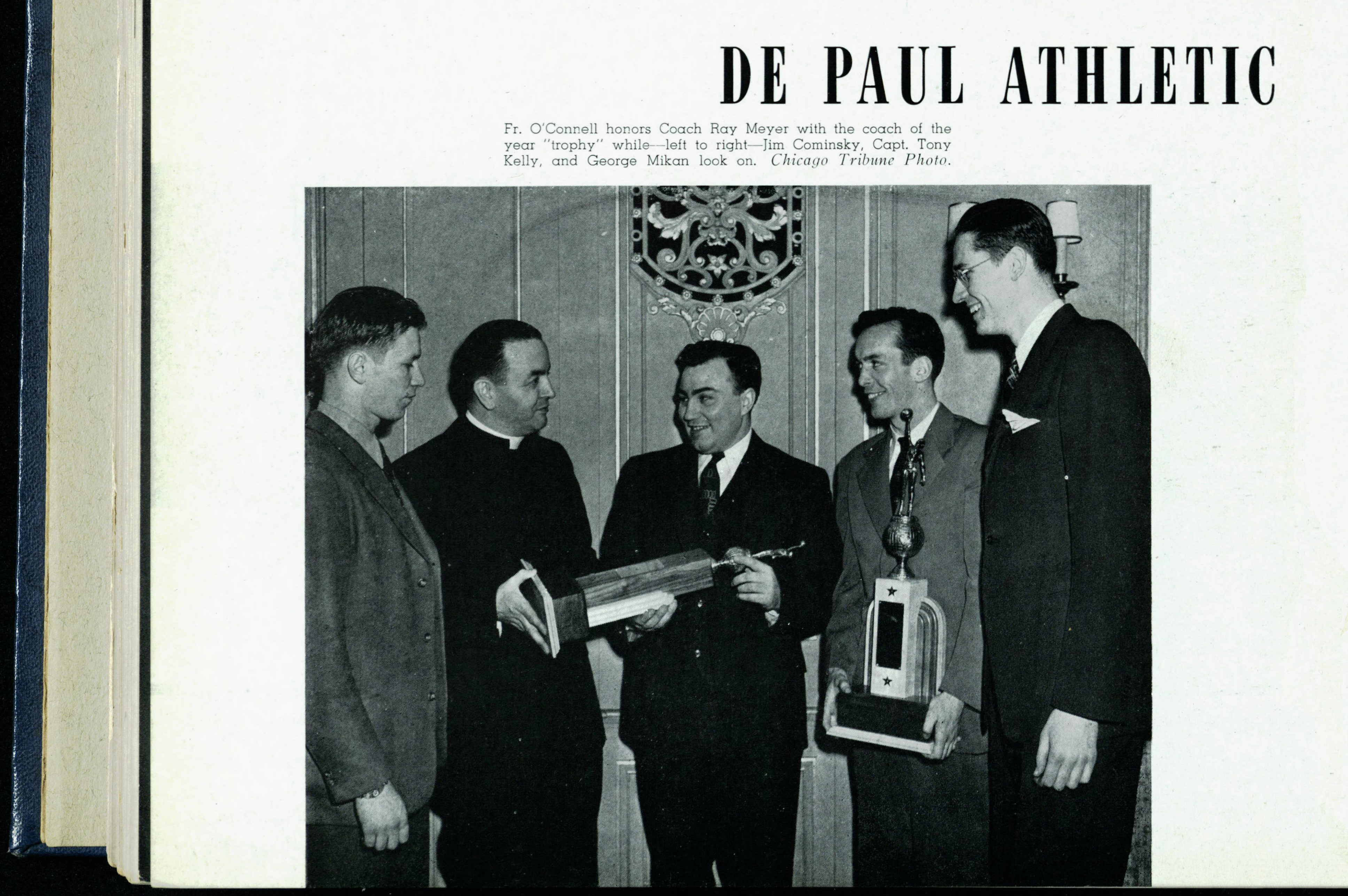

Lo and behold, the private school below the Chicago Brown and Red line train tracks became the center of national attention in a city that had yet to witness the triumph of Michael Jordan or the sweetness of Walter Payton. Even more, this very school was home to the great basketball legend George Mikan just forty years earlier. It was DePaul on the front page of Chicago newspapers as opposed to the Bulls; DePaul’s climb seemed as if it could only continue.

The late Mikan, a former All-Star NBA center, referred to Meyer as the man that “made DePaul a real power in basketball history.”

Chicago Public League players continuously bought into DePaul as the premier basketball destination with homegrown inner city talents such as DePaul’s Mark Aguirre going No. 1 in the 1981 NBA draft and DePaul’s Terry Cummings going No. 2 overall in the 1982 NBA draft.

Meyer then gave the reins to his son Joey Meyer following his 1984 Sweet Sixteen loss to Wake Forest.

Through such television exposure highlighted by the Aguirre-Cummings years, DePaul’s recruiting under Joey Meyer expanded as top-10 national recruit Rod Strickland from the Bronx, New York committed to the Blue Demons in 1985.

Joey Meyer led the DePaul men’s program to seven NCAA tournament appearances in his first eight seasons before the downward trajectory began to hit in the early 1990s, making their last 20th-century tournament appearance in 1992. Their 1996 season marked a program worst record at 3-23. Then-athletic director Bill Bradshaw fired Meyer, with academic problems and injuries as key reasons to the team’s poor performance.

Yet, the biggest of DePaul’s basketball problems was a giant cactus just beginning to produce its thorns. Oh, and the thorns began to peck the program more and more and more. DePaul’s basketball program grew drier and drier and the cactus became exposed.

DePaul’s pinnacle of success had been reached and a dry deserted climate awaited.

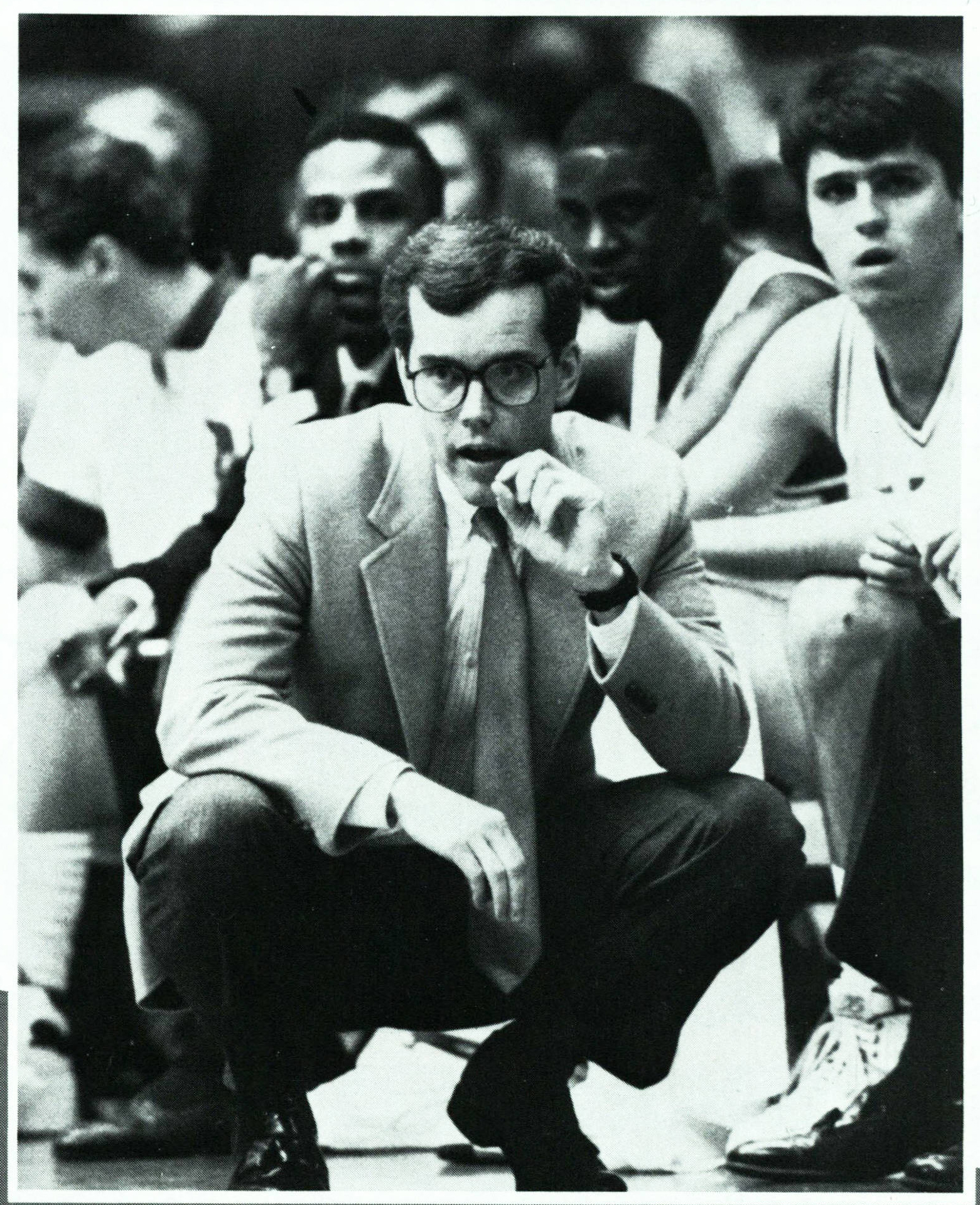

Joey Meyer pictured in DePaul’s 1990 yearbook.

Prosperity to Problem

DePaul’s success particularly in the Meyer eras largely loomed on the shoulders of the Chicago Public League as the likes of Aguirre and Cummings hailed from local public schools. The arrival of the quiet Teddy Grubbs in 1980 sparked noise for Chicago basketball fanatics as the 6-foot, 8-inch forward became another highly touted local Chicago star to commit to DePaul. Yet what sparked more noise was Grubbs’ inability to effectively produce under Coach Ray Meyer.

Grubbs, an All-American at King High School coached by the well-known Chicago Public League coach Landon Cox, battled personal and psychological problems while at the university. Grubbs’ problems were magnified by Cox as he faulted DePaul for wrongly handling the young man’s situation.

Grubbs dropped out of DePaul in the midst of his junior year during the 1981-82 season. Grubbs was later charged for battery in 1983 while at Peru State University.

In fact, Cox strategically began pushing Public League players away from Meyer and DePaul. Cox, along with a few fellow public league coaches, vowed to never send a player of theirs to DePaul University again.

In a 1997 Chicago Tribune report, Cox publicly stated players such as Efrem Winters would not play for DePaul “because of what they did to Teddy.” Winters went on to play for a downstate competitor in Champaign at the University of Illinois.

Sports attorney Philip Meyers, also a Chicago basketball analyst, said, “Chicago Public League coaches broke down their relationship with DePaul.”

Former DePaul assistant Robert Collins, a longtime Public League coach, stated in that same 1997 Tribune report that DePaul was unfairly blamed for the problems Grubbs faced.

Legendary Chicago news and sports journalist Toni Ginnetti acknowledged the tiff between Cox and DePaul as a pivotal factor in the recruiting world but also pointed toward a broader picture, as the landscape of college basketball changed on a national level.

Coach Cox was unable to be reached for the story following several phone calls and voicemails.

Ginnetti explained the success sustained within the Meyer eras: “DePaul was always able to get after the big-name recruit anywhere in the country because they had a platform with WGN.

“There was no ESPN. Now, everybody is on television. It’s such a big money thing now,” she said.

The creation of ESPN in 1979 and emergence of the sports program in the mid-1980s neutralized the advantage DePaul had as games were nationally televised at a lesser rate. The majority of DePaul games were telecasted via WGN in the bulk of major markets.

Following the creation and expansion of the network in 1979, ESPN became the WGN for every college team, not just DePaul.

DePaul was the only team to have their own local and national television contract at the same time because WGN was a superstation. As years went on, their national recruiting largely diminished as a result.

Issues within the leadership department became more and more problematic as big-name schools began successfully prying local Chicago stars away from home.

“A team is not just the team on the floor,” Ginnetti said, “it’s a combination of everybody being on the same page, of everybody having the same goals beyond just the tournament.”

“Recruiting becomes a factor in there, I don’t know if ‘ethics’ is the right word,” she continued.

In a 1997 interview with Bob Sakamoto of the Chicago Tribune, former Westinghouse coach Roy Conditto pointed to DePaul’s abandonment of the origin of their success, saying Chicago Public League coaches felt the school had neglected the very source of what put them on the map.

DePaul began thinking like a big-name Duke or Kansas, Conditto said, chasing big-name stars from coast to coast.

“I think that there was a feeling amongst some of the coaches and people at the top who were there that maybe we can use short cuts,” Ginnetti said. “Short cuts are not an effective way to do things.”

Post Meyer Era

Following Joey Meyer’s departure, Bradshaw hired Pat Kennedy to take on the charge. Kennedy successfully brought in Chicago stars such as Bobby Simmons and Whitney M. Young Magnet High School star Quentin Richardson as DePaul made a run in the NCAA tournament in the 1999-2000 season. However, Kennedy’s stint was short-lived, as athletic director Jean Lenti Ponsetto brought aboard the Jim Calhoun prodigy Dave Leitao.

Ginnetti extensively covered Leitao in his first stint with the university. She said, “He was the linchpin in recruiting for Jim; Dave was his right-hand man.”

Ginnetti recalled, “He would stress to them that though you may not be the best scorers, you can all play defense and keep a score low to stay in the game.”

Leitao resurrected the program in 2003 as the team won Conference USA in a league featuring college basketball guru John Calipari coaching Memphis, the legendary Rick Pitino leading Louisville and a stacked Marquette squad headed by an up-and-coming coach in Tom Crean. However, the 2003-04 season marked the last time DePaul basketball braved a court in the month of March, and the last time a Demon hopeful filled the letters “D-E-P-A-U-L” in a bracket space.

Leitao was pried away from the program following the 2004-2005 season as Virginia made a multimillion-dollar contract offer. As Virginia’s administrative brass flew west to Chicago to pick up Leitao in a private jet, the DePaul program, itself, flew south for miles and miles and miles for the next decade.

The programs southernmost trip landed them in an area of seclusion, where attendance has topped 8,000 just four times in the last decade. Both Jerry Wainwright and Oliver Purnell further sunk the program into mass disarray.

As DePaul basketball waned, so too did the fan base.

Lawrence Holmes, a veteran Chicago sportscaster at WSCR 670, said that “while there is a lot of history tied into the building in Rosemont, that history is far removed from 16- and 17-year-olds.”

Ginnetti recalled the coaching choices post Leitao as “good X’s and O’s coaches, but their thinking of recruiting was targeted toward the kind of player they used to recruit, the mid-major kind of player.” In reality, DePaul’s conjoinment into the Big East had them in the midst of basically a Power Five Conference.

Ginnetti went on: “You need a ‘major’ kind of player in the Big East conference.”

And thus, Leitao and DePaul meet again. Ginnetti’s voice softened, “When he left he said to me, ‘I know I’ll never coach again at a place like DePaul, where they treat you like family.’”

Under Leitao’s Wing

With no doubt, the familial aspect of the university is a major draw.

Walking out of practice in DePaul’s Sullivan-McGrath Arena, sophomore guard Eli Cain said, “It feels like a family here.” Coincidentally, just as he finished his statement, a fellow teammate came trouncing from behind, giving him a friendly smack on his behind. The teammates share a laugh.

Sweat drips down his face following the Friday morning practice. When asked why the New Jersey 2016 Big East All-Freshman guard chose DePaul, his face glimmered with assurance. “With Coach Leitao,” he said, “I was comfortable with the situation.”

In Leitao’s first stint at DePaul, the team reached the NCAA tournament in each of his years.

The reunion between Leitao and DePaul comes from a sense of trust established within the early 2000s. DePaul Athletic Director Jean Lenti Ponsetto’s eyes widened. “He has proven that he can win here at DePaul and against the caliber of coaches in Conference USA and in the ACC,”she said, referring to his time spent at Virginia against the likes of Duke’s Coach Krzyzewski and North Carolina’s Roy Williams in the Atlantic Coast Conference.

“For Dave coming back to DePaul, it’s not pie in the sky,” Ginnetti exclaimed. “He is in a conference with the defending national champions Villanova, who they almost just beat.”

The values shared between DePaul and Leitao were instrumental in Ponsetto’s decision to revert back to him. Ponsetto, sitting at her desk in a wooden-style office atop the Sullivan Center, said, “I think he was really attracted to coming back here because as you coach in college athletics around the country, philosophically, people look at programs in a different way.”

Proudly, Ponsetto continued: “At DePaul, it’s really about the total development of the student athlete along with the athletic and academic success.”

“It really is a function of recruiting and continuing to grow and develop the young men in our program,” she added.

From a recruiting standpoint, Leitao has a track record at DePaul for bringing in big-time talent. His first stint landed him future Pistons forward Sammy Mejia, Trailblazer forward Dorrell Wright and current Denver Nuggets forward Wilson Chandler.

“He recruits the East Coast but he knows how to recruit the Midwest,” Ginnetti said. His ties stemming from his first DePaul stint have already paid off. “In his first years here, he had a great player named Drake Diener who was from Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin.”

Drake Diener, the cousin of former star Marquette guard Travis Diener, helped pitch DePaul to incoming Cedarburg, Wisconsin, guard John Diener as he recently committed to the program for the 2018 season. He averages over 20 points per game as a sophomore playing varsity basketball.

From Allstate to Wintrust Financial

(JohnFranco Joyce, 14 East Magazine)

And so, after over 35 years of playing ball at Allstate, the Blue Demons look forward to the grand opening of the Wintrust Arena in the South Loop’s developing McCormick Square.

DePaul athletic director Jean Lenti Ponsetto proudly repeats the words of Coach Leitao as she refers to Wintrust Arena, “It’s a game changer in the eyes of the student-athlete.”

The $164 million arena project set to open for the 2017-2018 basketball season will feature a $1 million scoreboard with 10,387 venue seats, along with an attached Marriott Marquis Hotel already well under construction.

“I’m curious if Wintrust will host some of the Public League and Christmas tournaments,” Lawrence Holmes said. “That’s part of the reason I think it’s such a coup for DePaul.”

“The strategic plan Vision 2018 was very specific about ways to bring men’s basketball back to the city of Chicago, and I think the intentionality of it was to make it an enhancement to the program and the facilities are critical to that,” Ponsetto said.

The arena is located on Indiana Avenue and Cermak Road featuring an all glass state-of-the-art design.

Holmes went on: “It will allow DePaul to showcase itself to some of the best players in the area.”

“So much of it comes from meeting the demands of the young people who are entering college in 2017, 2018 and beyond,” Ponsetto said. “It’s more of a hardship for our students to go out to Allstate. They prefer to have something more within the city.”

Considering the new location, students will be able to use their bright blue Ventra passes to access the arena as opposed to taking the dreaded bus ride out to Rosemont, Illinois.

“When we go on the road, we see the atmospheres [at schools like Creighton, St. John’s and Xavier],” Cain said. “When other teams go on a run, they get loud and get the home crowd going.”

Coach Leitao is no stranger to the power of an up-to-date facility, as he led a young Virginia basketball team into the grand opening of the $131 million John Paul Jones Arena in 2006. The process did not intimidate the experienced veteran coach, as he led the team to a share of the ACC title in 2006-2007.

His towering presence is furthered by his deep, powerful voice. Coming out of a practice that consisted of lots of Leitao screams, his voice cracked in and out. “What everyone talks about in sports is having a true home court advantage,” he said.

Since Joey Meyer’s debacle and firing, the program has had just six winning seasons in 20 years. As a result, students watching a game at Allstate could play musical chairs.

“Wintrust can create a better home court advantage: location, interest, newness, all the things that matter when you have a new building,” Leitao said.

The construction of a new, partially city-funded arena in the developing South Loop creates an external interest in the DePaul men’s basketball program.

“The newness will certainly be an attraction,” Ponsetto said, “but I also think it is incumbent on us as an athletic program to put a very competitive product out on the court that students would be excited about.”

“We’ve got to be prepared to take advantage of that [newness],” Leitao said, “and give ourselves a chance initially to give ourselves a better home court advantage than we’ve had.”

It’s fair to say, Leitao realizes Chicagoans don’t follow the wind; they follow the winner.

“You get a plan, you put that plan in place and allow the players to grow,” Leitao said. “Winning then becomes a part of that.”

And so, DePaul’s presence in Rosemont’s Allstate Arena, too, has dried itself out. Their transition from Assembly Hall into Allstate Arena and out has come full circle.

DePaul’s perennial dominance in the 1970s pushed them to the bigger and better playing platform at the 18,000-seat Allstate Arena in 1980. Yet, their utter decline left far too many open seats, far too many half-loaded student buses trekking down I-90 and little reason to even care about the storied Chicago men’s program.

And now, 37 years later, DePaul men’s basketball will make their way back into the city and hopefully back into relevance.

March 1 marked the 526th and final game for DePaul at Rosemont’s Allstate Arena. Memories of program’s success and victories will remain within the confines of the building, but bodies and dreams will disperse.

“It’s a sleeping giant. The program can be good again,” Meyers once assured.

Their recent failures will undoubtedly carry on with them as they move into Wintrust Arena. Yet they will hope to start anew behind the freshly paved brick and mortar. It largely rests on the shoulders of DePaul to bring college basketball back to the city of Chicago.

“You live in Chicago, you compete with the Bulls, the Blackhawks, with plays, movies, museums,” Meyers said. “People in this city expect top-notch product, competition and opponents.”

Chicagoans follow winners. Look at Northwestern, look at the Cubs. Droughts can end; fortunes can change.

(JohnFranco Joyce, 14 East Magazine)

Header image: Ray Meyer accepts a coach of the year trophy in an image from DePaul’s 1946 yearbook. George Mikan is on the far right.

NO COMMENT