Few colors stood out in Studio A — one of the two studios at engineer Steve Albini’s recording complex, Electrical Audio. The walls were gray. A wooden analog clock sat in the center of a light brown wooden beam, encasing the window through which the studio’s engineer watches musicians as they record. Recording equipment radiated red digits redolent of digital bedside alarm clocks. The master mixing board was massive, with gray and blue knobs, their shades dull and inoffensive.

Next to the studio’s entrance were Ramones blow-up dolls and a hand-drawn pencil sketch of Steve standing at a mixing board with cartoonishly straight legs spread out like a “v.” Cartoon Steve wore a jacket with a large lower-case “e” on the back, which (presumably) stands for Electrical Audio. Under his feet, Microsoft WordArt-esque letters displayed the words “STEVE ALBINI. MIX LIKE A BOSS.” Beside the drawing were three AA batteries – all from different companies – a small bottle of aspirin, a number-two pencil and a deck of old playing cards.

(Madeline Happold, 14 East Magazine)

14 East reporter Madeline Happold and I waited in Studio A as we prepared for our conversation with Steve Albini, one of the most prominent figures in underground punk rock. Steve is known for the bands he has recorded, performed and toured with including Big Black, Rapeman and his current band, Shellac. But perhaps most famously, Steve is known for his audio engineering on In Utero, Nirvana’s third full-length album, which featured some of their most classic recordings including Rape Me, Heart-Shaped Box and All Apologies.

As Steve made himself a coffee in the studio’s modest, unkempt kitchen, Madi and I photographed his all-analog studio – these studios are a rarity now that the music world has fully immersed itself in digital-based engineering.

Steve entered the studio wearing a shirt with the face of a wolf on it and a small hoop earring in his right ear. He wielded a tall glass of a coffee-like beverage with a noticeably massive portion of foam resting on top.

“Before you leave, you should ask Taylor to make you a fluffy coffee,” he said, referring to Electrical Audio engineer Taylor Hales. Steve’s mannerisms suggested that “fluffy coffee” is a word as widely recognized as “cappuccino” or “latte,” though Madi and I had never heard of it.

Sheepishly, I gave in to my curiosity and asked, “What is a fluffy coffee?”

“It’s a coffee drink we invented here,” Steve said.

It’s a complex drink.

“It’s a double shot of espresso, with a lot of steamed milk and maple syrup. The espresso is special in that it has cinnamon mixed with it so when you draw the shot instead of getting — like if you dump cinnamon in a regular coffee you have like little granules of cinnamon floating around in it and cinnamon mud at the bottom of your cup. This, the cinnamon flavor is shot out of it with the coffee flavor in the espresso. So you get a cinnamon flavored shot and then the maple syrup in the milk. Maple syrup is mixed with the milk before it’s steamed so the foam gets this like marshmallow consistency that’s really incredible and it’s super delicious.”

Steve said he drinks three fluffy coffees a day. That is, when he is not on tour with Shellac.

“We tour every year,” he said, adding that the primary motivation behind starting Shellac was to play live.

Since their inception in 1992, Shellac has released five full length records.

Considering Steve’s massive output as an engineer, which he said includes over 1,000 records to date, it wouldn’t be irrational to label him as truly prolific. But Steve insists that his heavy flow of work is more out of necessity than it is a personality trait.

“If I worked less, then I would go broke and people would come and take all my stuff away,” he said. “And I don’t want to do that. I just got a house! I really want to keep it!”

Shellac tours constantly, but only occasionally releases music.

“My band puts out a record every five or 10 years,” he said.

Certainly not prolific.

Over the years, Steve has garnered a controversial yet well-respected reputation for his aggressive perspectives on the music industry, on music taste and on recording practices. Among Steve’s more famous contrarian attitudes is his unwillingness to budge on his preference to analog over digital recording practices. As popular as Steve is in the recording world, even among the currently digital-dominated landscape, it is unlikely that he will ever record an album digitally.

Steve’s reluctance to change with the contemporary trends of recording music does not come off as surprising. In 1993, he published an article in The Baffler entitled “The Problem With Music.” Ruthless is not expansive enough a term to describe the tone of the piece, which dives into Steve’s issues with major record labels, then-contemporary engineers and self-described “producers.” In a section titled “What I Hate About Recording,” he gives people an early taste of his low opinion of digital recording technologies in his discussion of DAT machines, or machines that digitally record audio to tape.

“Tape machines ought to be big and cumbersome and difficult to use, if only to keep the riff-raff out,” he wrote. “DAT machines make it possible for morons to make a living, and do damage to the music we all have to listen to.”

His use of name-dropping in the article is capable of shocking readers, particularly when he likens the idea of calling Don Fleming, Al Jourgensen, Lee Ranaldo and Jerry Harrison “producers” to “calling Bernie a ‘shortstop’ because he watched the whole playoffs this year.”

When Steve wrote “Bernie,” he meant it to represent any average person, like “Joe Schmo.”

Later in the article, he continues his anti-establishment crusade with a discussion of specific independent labels including SubPop and Twin/Tone. According to Steve, these labels were only independent “in name, but operated in the principles of a bigger record label.” In other words, Steve sees these types of labels as exploitative to the musicians they sign, including Nirvana, Babes in Toyland and Poster Children.

In retrospect, Steve expressed some level of guilt for making an example out of bands he knows, loves and respects.

“I had legitimate reasons for doing it,” he said. “The consequences were that other people had to answer for something that I wrote, and that makes me feel bad and I am apologetic about that.”

Steve doesn’t know if there was a better way to get his larger point across: the music industry leeches onto talented bands, monetarily leaving musicians they sign on the short end of the stick. Nevertheless, Steve remains friendly with the bands he discussed and still occasionally plays shows with Poster Children.

Shellac and Poster Children, among other bands, are scheduled to play a benefit show for ACLU and The Southern Poverty Law Center called “All Tomorrow’s Impeachments” this July 22 at the Bottom Lounge in the West Loop.

(Madeline Happold, 14 East Magazine)

Naturally, Steve’s highly critical articles have considerable potential to attract backlash and damning assumptions about his personality. And although he is well aware of his reputation among musicians who have never personally met him, Steve revealed little-to-no concern about his public image.

Steve figures most rumors exist about his personality because of a developed “mystique” from stories that are “third, fourth, fifth hand, sometimes invented out of cloth.” But as the circle of people he personally knows continues to grow, the more “the gossip and the nonsense” will be neutralized.

“You can’t do anything about it,” he said in reference to himself. “So I tend not to worry about it… Over time, the more people I interact with directly, the less of this sort of ephemeral ghostly invented gossip there is.”

Another misunderstanding manifests itself in Steve’s desire to continue working with tape instead of digital recording; typically, analog engineers are expected to discuss their affinity for a “warmth” contained in analog sounds that is lost in the binary code of the digital medium. In fact, Steve confessed his contempt toward descriptive words like “warm” and “punchy” in the aforementioned “The Problem With Music” article.

“Every time I hear those words I want to throttle somebody,” he wrote.

(Madeline Happold, 14 East Magazine)

For Steve, his preference to analog is informed by more practical purposes than auditory. Steve has spoken a great deal about his skepticism toward the safety and accessibility of digital recording. If he continues recording to tape, he feels guaranteed that the record’s longevity will be infinite, a feeling he does not have toward digital recording. The way of thinking is rooted in the idea that digital recording studios use proprietary technology from specific software companies such as ProTools or Logic. These technologies are updated regularly, which renders old recording sessions obsolete unless the sessions are updated in congruence with the technology. Analog formats, conversely, are universal and have the versatility to be converted to digital, thus making analog a much more open format to engineer with.

Steve is a man with independent opinions that often collide with mainstream and underground music scenes, and he is unafraid to express them. At one point he playfully poked fun at my shameless affinity for Sublime’s music after he learned I was from Southern California.

“I have some friends who like them,” he said smugly after I revealed my guilty pleasure.

“I think they made good music but inspired a lot of crap,” I replied, foolishly likening their influence to Nirvana’s.

Steve disagreed.

“Very few bands directly inspired by Nirvana actually exist,” he said. “But I think the majority of the bands that are referred to as contemporaries of Nirvana that were tagged as being influenced by them, I think they were trying to do their own thing and failing.”

Touché, Steve.

Strangely, even when he was clearly joking or expressing a contrarian point of view, Steve remained calm and mild-mannered. It’s not that he’s quiet; he just doesn’t seem to ever raise his voice with passion or emotion. Yet Steve’s somewhat monotonous level of expression was shattered by his bizarre sense of humor that would emerge out of nowhere. Steve digs what he digs, and legitimately does not care whether or not people understand him, whether it’s his taste in music or his taste in comedy.

On Electrical Audio’s website, there are photos of all of the staff. If you click on any of the engineers’ photos, their contact info appears. But not Steve’s.

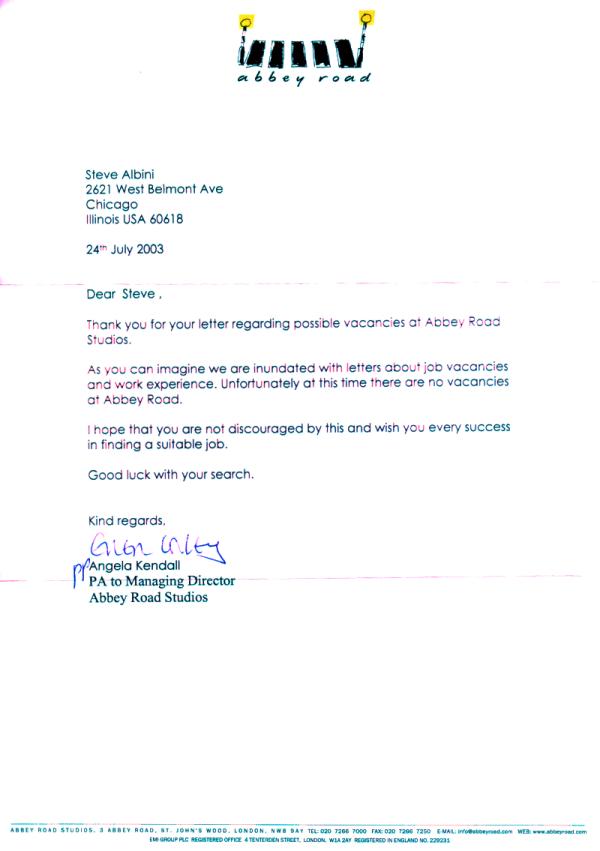

If you click on Steve’s photo, the website redirects you to an image of a rejection letter from Abbey Road, a historically recognized studio in England, addressed to none other than Steve Albini. When I asked him what that was about, he laughed and seemed to have forgotten that he had put it up.

“Oh yeah. That was funny,” he said.

Steve was familiar with everybody who worked at Abbey Road, having made several records there including one that took “the better part of five months.”

As a prank, someone sent a letter inquiring about job openings at Abbey Road in Steve’s name to Allen Parsons, Abbey Road’s managing director at the time.

“[Parsons] had drafted a very straight, very formal declining letter, sort of playing along with the joke,” he said. “And that’s what that PDF is. The PDF is the rejection letter from Abbey Road saying ‘No, we have no positions currently,’ basically.”

He told me they used to have a printout of the letter framed on the wall of Electrical Audio’s kitchen.

Electrical Audio’s kitchen walls have also featured other framed bizarre letters mailed to Steve. Beside the Abbey Road letter was another letter Steve received from the Kellogg Company expressing their apologies to Steve after he mailed them a Pop-Tart he purchased that had no frosting on it. Accompanying the Pop-Tart was a Post-it note that read “You call this a f–ing Pop-Tart?”

“And they sent me a very formal response back saying ‘we’re sorry that you were disappointed in your Pop-Tart.’ Whatever,” he said. “And we used to have that letter framed in the kitchen as well. Yeah.”

I asked him if the letters have since been discarded, to which he responded, “I don’t know. It might still be around. The Pop-Tart is long gone.”

Steve’s imprint on Chicago’s music scene is undeniably strong. Last December, I spoke with Maureen Herman of Babes in Toyland about Chicago DIY in the ‘90s. Her initial description of the scene included only one name-drop: Steve Albini.

Steve mostly agreed with Maureen’s description of the scene which, according to them, featured a stronger work ethic and less drug abuse than many other comparable DIY scenes.

“Over time it sort of encroached like it does in a lot of places,” he admitted, suggesting that the industrial rock scene was the primary culprit of bringing hard drugs to Chicago. “But there was a very long stretch where there was a very productive punk scene that had only a smattering of drug use.”

But while Steve has a great appreciation for Chicago – particularly over the Los Angeles or New York underground scenes – he began living in Chicago because of college, not because of a draw to the city’s attractive work-driven underground community.

“I just kind of ended up here,” he said.

Steve was raised in Montana. In the late ‘70s, he was in what he described as an “inept punk band” called Just Ducky. They played two shows, one of which was at a high school dance. The show was stopped early because the chaperone didn’t like the music.

“We were the band,” he said. “There were no other bands.”

So when Steve moved to Chicagoland to go to Northwestern, it was his first introduction to any kind of music scene. Once here he became immersed in the local culture, primarily through his affinity for punk rock.

“That could have happened to me elsewhere,” he said. “Like if I had gone to Kentucky, I could have gotten integrated into the Louisville underground music scene. If I had gone to New York, I could have gotten integrated into the New York underground music scene. But I ended up here.”

But as Steve continued playing music and going on tour with his bands, he developed an appreciation for Chicago’s underground scene over the scenes on the coasts. Steve considers most of the scenes on the coasts to be full of needless competitiveness and “top dog” mentalities.

“If you’re in New York or Boston or another big coastal city or whatever, you have to deal with a bunch of jack-offs,” he complained. “Like their music is awful and the scene is awful and everybody’s terrible.”

Steve was always more impressed with “places that were not media centers.” He spoke highly of Louisville, Columbus, Milwaukee and Minneapolis in addition to Chicago, where “people tended to do things to amuse themselves rather than to impress other people.”

“They’re not trying to make an impression,” he said of non-coastal underground scenes. “They’re doing something because they’re driven to do it.”

Steve’s style of engineering is simple. Anything he records will be analog, will mostly lack excessive overdubbed tracks and — most importantly — will be artistically driven by the band.

“The easiest way to put it is: I consider the band to be the producer of their own record,” he said. “They get to make all the decisions.”

(Madeline Happold, 14 East Magazine)

Although his approach is seemingly hands-off, a typical Steve Albini-engineered record has a signature sound that his fans easily recognize. According to Steve, his goal for the records he engineers is to produce music that can be easily reconstructed live. Such a result requires a specific work ethic. According to Dylan Baldi of Cloud Nothings, Steve spent most of his time “playing Scrabble” while he recorded Cloud Nothings’ “Attack on Memory,” adding that Steve very well might not be able to remember how the album even sounded. Though such a statement may come off as pejorative, Baldi was well aware of Steve’s hands-off approach to recording when he chose Steve to be the engineer, and was particularly appreciative of Steve’s ability to record drums well.

Since Steve is constantly recording bands, he is able to recognize that some bands will leave a session feeling frustrated from the experience. Perhaps most notably, Steve’s engineering on Tweez by Slint inspired considerable criticism from Ethan Buckler, Slint’s bassist at the time.

“You drop the ball sometimes,” Steve reflected about himself. “Sometimes you do a bad job. I’ve punted some records and that’s inevitable. When you do something enough times, you’re going to screw it up now and again.”

At the time, Steve was still a young engineer, working as a photographic retouch artist for income and only recording on the side.

“I was a little headstrong,” he admitted after mentioning that “there were kind of competing aesthetics within [Slint].”

While Steve is one to defend his opinions to their end, he is capable of recognizing his own shortcomings. Certainly, being a ex-member of a band called Rapeman while announcing he tries to be an ally to feminism contains considerable possibility to question his judgment. Retrospectively, Steve appeared embarrassed about his old band’s name.

“Yeah, the name Rapeman was chosen kind of capriciously and thinking of it now as a more enlightened person it just seems unconscionable,” he said. “I can’t imagine why we did that. It’s indefensible.”

After we wrapped up our two hour interview, Taylor Hales brought us some complimentary fluffy coffees while Steve began to prepare the mixing board for his next session.

“These are revolutionary,” Madi said.

Steve nodded in agreement, but looked unsurprised.

“Yeah I regularly bemoan the fact that I bothered building this f–ing studio and going millions of dollars in debt when I could have just had a little kiosk … selling these.”

He finished his preparation, then stood in the studio’s doorway.

“Um… Feel free to relax,” Steve said. “Enjoy yourselves. I’m going to go upstairs and disappear. You guys can let yourselves out!”

And Steve disappeared as the fluffy coffees disappeared from our glasses. They were super delicious.

(Maxwell Newsom, 14 East Magazine)

Header image by Madeline Happold.

NO COMMENT