The spectrum of experiences in Chicago is as diverse as a Red Line train flying across the city at rush hour. Despite that shared moment of motion and physical stillness, despite being almost crushed by the closeness of other passengers, it still is difficult and even taboo for Chicagoans to talk to one another about our shared world. However, by extending its branches to different people, parks, neighborhoods and experiences, Collaboraction’s Peacebook Festival is attempting to cover the Chicago breadth of experience on the topic of violence.

“We have over 200 artists from all over the city doing things — so sure, there’s a little bit of chaos — but that’s like part of the joy of it,” said Peacebook playwright and director Sarah Illiatovitch-Goldman. “Unlike so much theater, the point of this isn’t how pristine it is; it’s how real it is.”

After working at the company for 15 years, Artistic Director Anthony Moseley decided in 2012 to rewire Collaboraction’s central mission to focus on the issues of systemic racism and violence in Chicago. Around the same time, the Chicago Park District launched its Night Out in the Parks series, which provides over 1,000 nights of arts programming city-wide. After a marathon performance of the festival’s 24 pieces at the Goodman Theatre in August, Collaboraction’s Second Annual Peacebook Festival has emerged as a three-park program that seeks to re-funnel energy and give voice to the communities of Englewood, Austin and Hermosa.

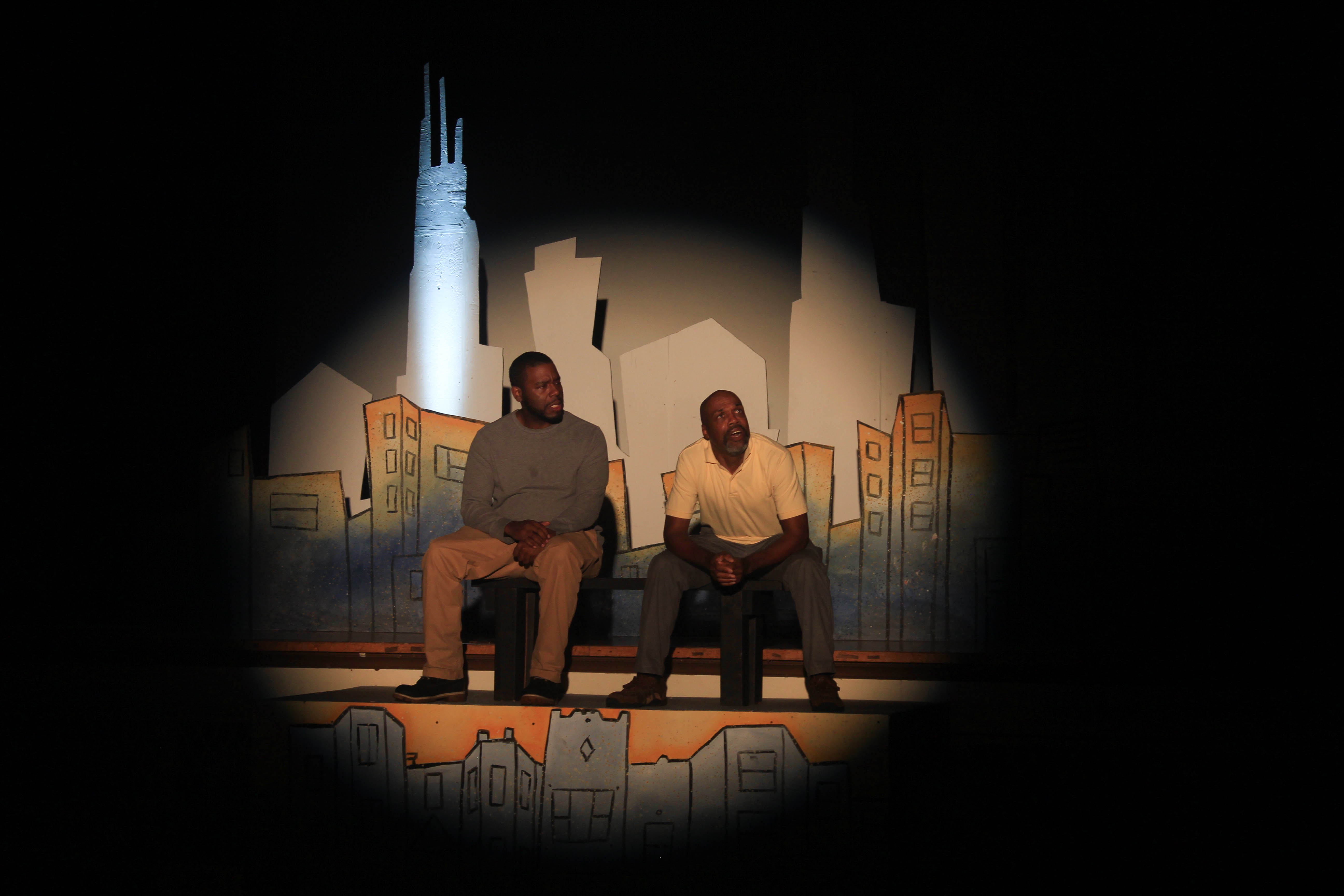

Kenneth Johnson and Brandon Boler discuss grief while waiting for a train in “Dandelions” (Meredith Melland, 14 East)

“We’re trying to inspire individuals to be the change that Chicago needs to change our history of inequity,” said Moseley. “We think that theater can really light that spark.”

At least three of the eight shows in each neighborhood were devised or performed by members of that community, according to Moseley. The Englewood performance occurred at Hamilton Park from Oct. 5 through 7, and the Hermosa and Austin performances will happen Oct. 19 through 21 and Nov. 2 through 4 respectively, each showing eight of the 24 shows.

“There’s definitely more of a thrust on making sure that we’re finding artists from the neighborhoods we’re touring to,” Moseley said.

The artists involved in these shows come from a range of experiences and backgrounds but are tethered to overlapping concepts of violence for each of the three rosters: racism and street violence are explored in the Hamilton Park shows, immigration and cultural erasure loom large in the Kelvyn Park arch, and crime and identity arise as themes in the La Follette Park lineup.

Hermosa

The Hermosa eight-piece show coming up for Oct. 19 through 21 showcases three personal stories of immigration to America: one of a relative’s 40-year evolution as a Mexican woman in America, one personal achievement of citizenship from Taiwan and one refugee fleeing war in Syria and seeking truth in theater.

“Eckhart Park Echoes” follows the stories that Nancy Garcia Loza’s aunt, who died in March, told her one night about immigrating alone to West Town in search of her father in the 1970s.

In writing her piece for Peacebook, Loza wanted to push back against simplistic and male-dominated portraits of Latinx life found in American culture in media.

“I think especially right now, people want us to be invisible, especially the women,” Loza said.

“The Mexican woman’s experience, it always seems to want to be erased,” said Loza, playwright and Co-Creative Director of The Alliance of Latinx Theater Artists of Chicago.

“I think with this piece I wanted to just remind folks that erasure is a form of violence,” Loza said.

Another story of immigration and personal experience comes from former DePaul sociology professor Dr. Ada Cheng, who resigned from teaching in 2016 to pursue storytelling full-time.

“When I was in the classroom, I realized that changing minds is not enough, right?” Cheng said. “Unless you talk to their hearts, just changing their minds isn’t enough.”

Cheng’s piece, an excerpt from her first solo show, uses her own path to immigration to the U.S. for education to allow the audience to experience uncertainty through her story.

“When I take an audience member through that process, I was talking about the vulnerability of when you don’t have a piece of paper in your hand,” Cheng said. “Having that thing legalized and having a sense of home are totally different things.”

Sami Ismat, the playwright behind “Finding a Loving Motherland,” immigrated to the U.S. in September 2016 to leave the war in his native Syria, where he returned home after going to the U.K. for university. He devised his piece with a group of Chicago actors initially unfamiliar with the nuances of the Syrian refugee crisis.

“For me, I think it’s really important to tell the story of these people who fought for something and no one supported them,” Ismat said. “And they ended up losing and ended up being labeled as the problem.”

Ismat said the Syrian refugee journey “is really the story people need to hear, because that’s the one they don’t know.”

Ismat advocates for more support for theater activism like Peacebook. “It has a really important goal . . . they are trying to spread experiences of people who are living in our world who have suffered,” he said.

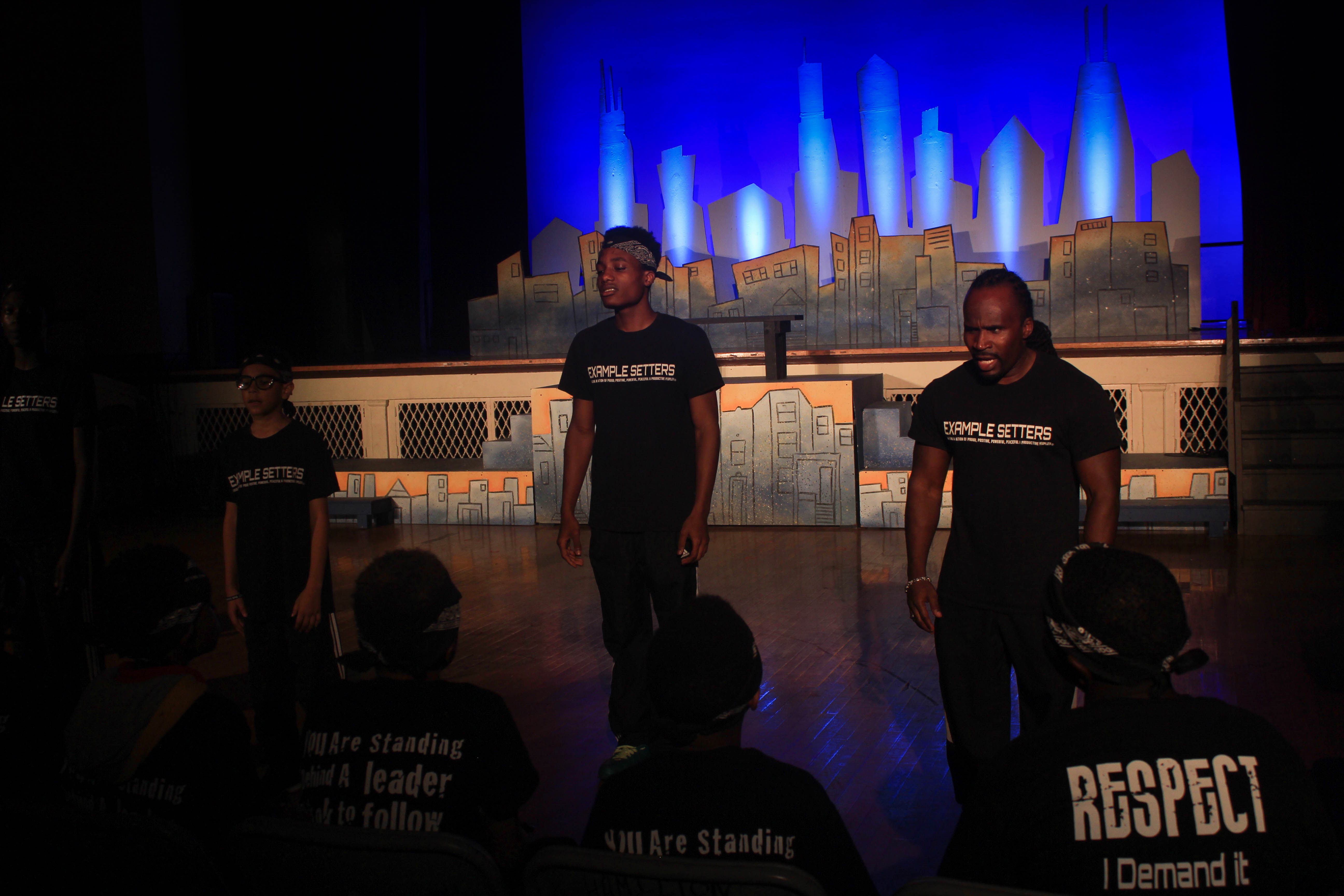

Sir Taylor leads The Example Setters in an almost military-like cadence call (Meredith Melland, 14 East)

Austin

Many of the shows on the lineup at Austin are similar in topic to the shows of Hamilton Park: both shows grapple with the complexities of race, crime and death. At these Peacebook shows, the creators also approach concepts of identity and racial accountability within the diverse and vibrant neighborhoods in Chicago.

For her piece — “Some Thoughts On Race and Racism In Chicago From Some People Who Aren’t Sure What To Do And Who Sat Down And Talked About It” — Illiatovitch-Goldman conducted interviews with 35 white people and boiled them down to a seven-minute verbatim theater piece.

“The play is a whole diverse cohort of people taking on the voices of about 30 different white Chicagoans as they wrestle with race, racism and accountability,” Illiatovitch-Goldman said.

Stories of personal introspection, of Chicagoans trying to find direction among the skyscrapers and shadows, are interwoven at Austin. “Dear Masculinity” is a work based on letters that young men have addressed to their own sense of masculinity and of manhood, and “17 to (New) Life” follows an incarcerated black man’s search for transformation and redemption.

Englewood

In the rainy Friday twilight of Peacebook’s first weekend in the parks this fall, the Hamilton Park grounds are quiet. Inside the Hamilton Park Cultural Center, in the gymnasium-floored, high-ceilinged auditorium, a crescent row of middle school-aged boys beatbox in front of the stage led by performer Yuri Lane. High-tempo music fills the gym under the guidance from the DJ near the stage door. The backdrop for the show is a colorfully lit cutout of the city’s skyline, which fades to dark against the spotlight as Moseley announces the start of the night’s show. He encourages the audience to come back the next day before the performance for a dance battle and community meal of comfort food for 300.

Dwayne Ellison acts as the personified version of Englewood in the Chicago art therapy play entitled “Hoods” (Meredith Melland, 14 East)

The performance opened with the Kaye Winks piece “Hoods,” which depicted an art therapy session with personified versions of specific Chicago neighborhoods, including Humboldt Park, the Loop, Englewood and chipper college student and pet-enthusiast Lincoln Park. “#Hashtag Who’s Next the Musical” put a police brutality saga into song. “Dandelions” chronicled a black couple mourning the death of their granddaughter by stray bullet. The rhythmic shouted-word piece “The Example Setters” featured black young adults making calls and responses led by their leader, Sir Taylor. Taylor leads them out in front of the stage and conducts the group in a few unified deep breaths before they explode into a performance that is part blocking, part rap and part poetry.

“Who are we?” Taylor bellows.

“Example setters!” The shouts echo.

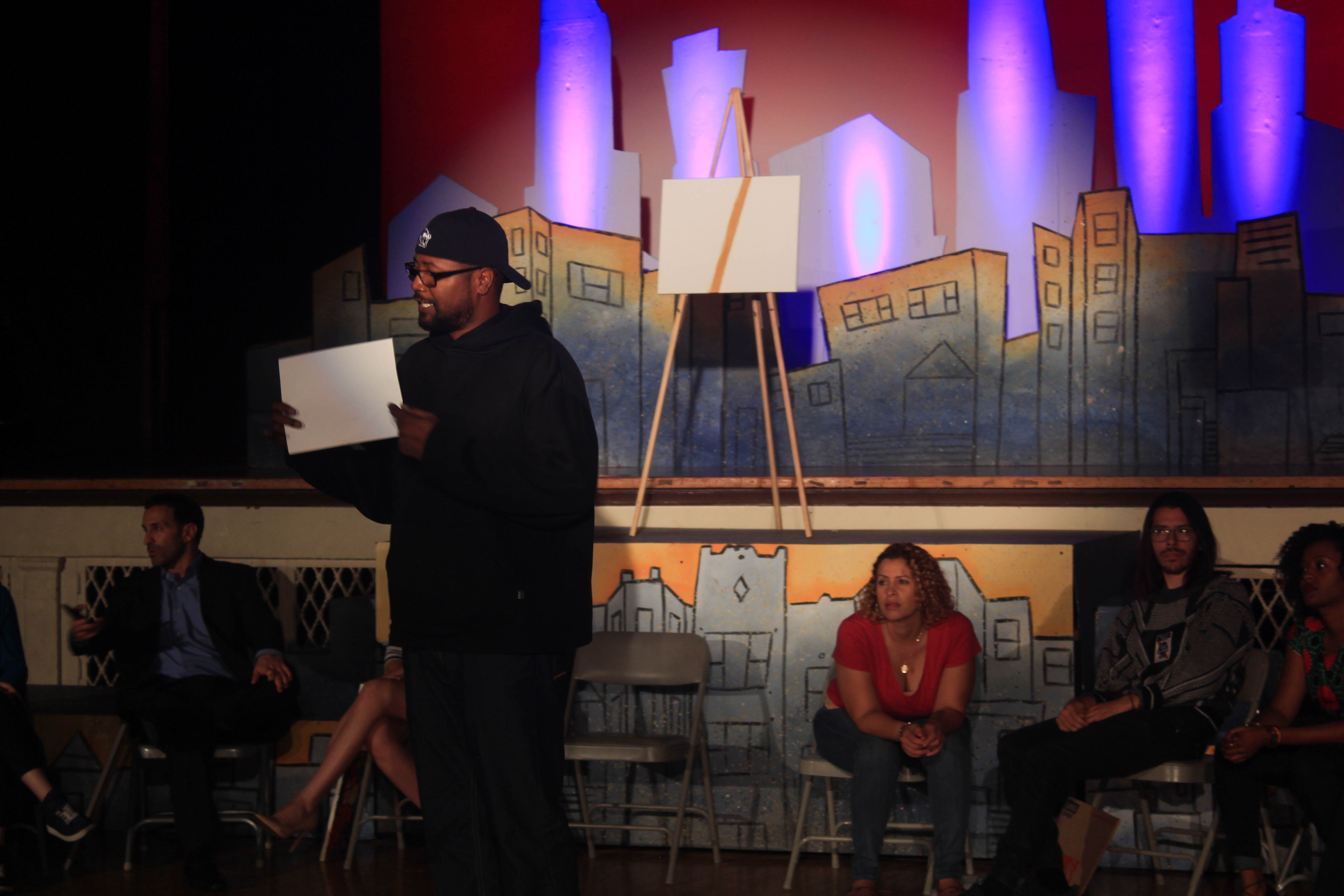

Cast members of “The Example Setters” breathe in unison before launching into a new segment of the piece (Meredith Melland, 14 East)

During the ending rap, guitar, beatbox and harmonica number “Make Peace,” Moseley tap-dances onto the stage and jams with the performers. He walks downstage and asks for feedback from community members as the gym’s lights are brought up. A few members of the small audience speak up from the bleachers and say that they appreciated the content of the show; Brenda Woods, who teaches dance in the Hamilton Park building and brought her grandkids to the show, commented on how glad she was to see the kids and later referred to the show as “soul-shaking.” The DJ puts music on then fades it out, and everyone begins to pack up and peel off in different directions, the performers and technicians chatting and laughing. Moseley makes sure everyone left has a ride home before exiting in a bubble of cast and crew into the rainy night.

Artistic Director Anthony Moseley dances with one of the members of The Example Setters (Grace Juracka, 14 East)

Correction: a previous version of this story misquoted Nancy Garcia Loza as saying the phrase “a race” when she in fact meant “erased.” The post has since been updated.

NO COMMENT