Ricky Jay, storied magician, historian, actor and author, says that playing cards are like an extension of his hands—he knows their weight, their pliant maneuverability, as surely as he knows his own limbs.

“You sit in a room with them for 10 to 15 hours a day and they become your friends,” he muses in the opening credits of the 2012 documentary “Deceptive Practice: The Mysteries and Mentors of Ricky Jay.” His hands rove over a deck, fanning the cards in a neat half-circle. “Particularly for very lonely people.”

For Jay, cards are an integral part of the magic he performs, and thus a central tenet of his talk at the Student Center Wednesday as part of the DePaul Humanity Center’s series on “The Year of the Fake” and “In Conversation With Great Minds.” The talk, hosted by philosophy professor and Humanities Center director H. Peter Steeves, aimed to explore the ontological origins of magic and deception. What does it mean to perform magic? How do we want to be deceived?

On the surface, you wouldn’t guess Jay wrestles with these kinds of questions. He became famous in the ‘70s as a sleight-of-hand performer and actor, touring hotels and making the late-night TV circuit. His groovy look–wavy brown hair flowing halfway down his back, three-piece flared suits—suggested a tacky, variety show kind of appeal. One of his signature tricks involved flinging cards into the thick (“pachydermatous,” he said with an affected flourish) rind of a watermelon.

But beneath the camp, Jay proved himself a serious performer, deeply devoted to the cultivation of magic as an art form. He’s authored books “Cards as Weapons” and “Dice: Deception, Fate, and Rotten Luck” and collects antique dice and paraphernalia, some of which has been displayed at museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Beyond the realm of magic, he’s also carved out an accomplished acting career, frequently collaborating with playwright and director David Mamet and taking on character roles in movies like “Magnolia,” “Boogie Nights” and “Tomorrow Never Dies.”

Now, with his hair cut trim and his face slightly pouchy, Jay is a portrait of a magician aged. He broke his wrist a few years ago, he says, and the unfamiliar addition of pins and screws in his bones has shifted his entire approach to performance; he can’t trust that his hands will move with the same sureness they used to. And yet, his cult of personality persists.

“You want to see the legend, you know?” says John Demian, an audience member and a self-described medium and clairvoyant. “I wanted to see the great one, who I’ve heard about for dozens of years.”

A pack of unopened cards between two water bottles on the stage where Ricky Jay spoke (Brendan Pedersen, 14 East)

The audience—a collection of largely older, nebbish-looking men, many of whom are magicians themselves—are deeply invested in Jay’s pursuit of magical truth. Next to me, a man scribbles pages of notes in a Moleskine. “DECEPTION,” he writes over and over again in swirling, curlicue letters. On my right, another man drapes a hand studded with Freemason rings over the back of a chair. Directly in front of me, there’s an elderly man who keeps squinting at Jay through a pair of petite black binoculars.

Throughout the evening, Jay and Steeves volley back and forth about the meaning of magic, tossing out hypothesis after hypothesis. Magic is about narrative. Magic is an unwilling suspension of disbelief. Magic is (sometimes) meant for those with mathematical minds. Magic is like classical music, but it’s also like jazz.

But most of these audience members aren’t looking for some kind of magical absolution so much as a window into Jay’s mind. If they’ve practiced, they already have a pretty good handle on what magic means to them.

“I got started kind of late in life—I was in my early 40s, actually,” says Mel Siegel, an amateur magician and vice president of the local chapter of the International Brotherhood of Magicians, which had several other members in attendance. “But I always loved it. It was later on in my life, when I had my children, that I really pursued it and studied it.” He says magic, at its best, is meant to be fun.

Demian, who was standing near Siegel during our interview, disagrees. He says he channels magic through his painting (he mostly paints ancient Chinese dynasties), and that all answers come through the subconscious mind — through nominalizations, presuppositions.

“I went to art school for 10 years, but I study magic now more than ever,” he says. “Just the mind-reading stuff. I’m doing 250 paintings now on neurolinguistic programming.”

One thing all magicians, regardless of prominence, seem to agree on is a revulsion for the overanalysis of magic. Watching magic in a mechanical sense, they say, defeats its purpose.

Jay, for all his philosophical back-and-forth with Steeves, zealously subscribes to this line of thought. He says toward the end of the night that magic is ultimately about entertainment — not in the cheap, vaudevillian sense, but in pure spectacle. There is no keener pleasure than the moment of reveal, the involuntary gasp of the crowd: you expected this all along, and yet you cannot control that sharp intake of breath. For Jay, who is the deceiver, these moments are rare but precious.

“It is a wonderful thing to be fooled,” he says.

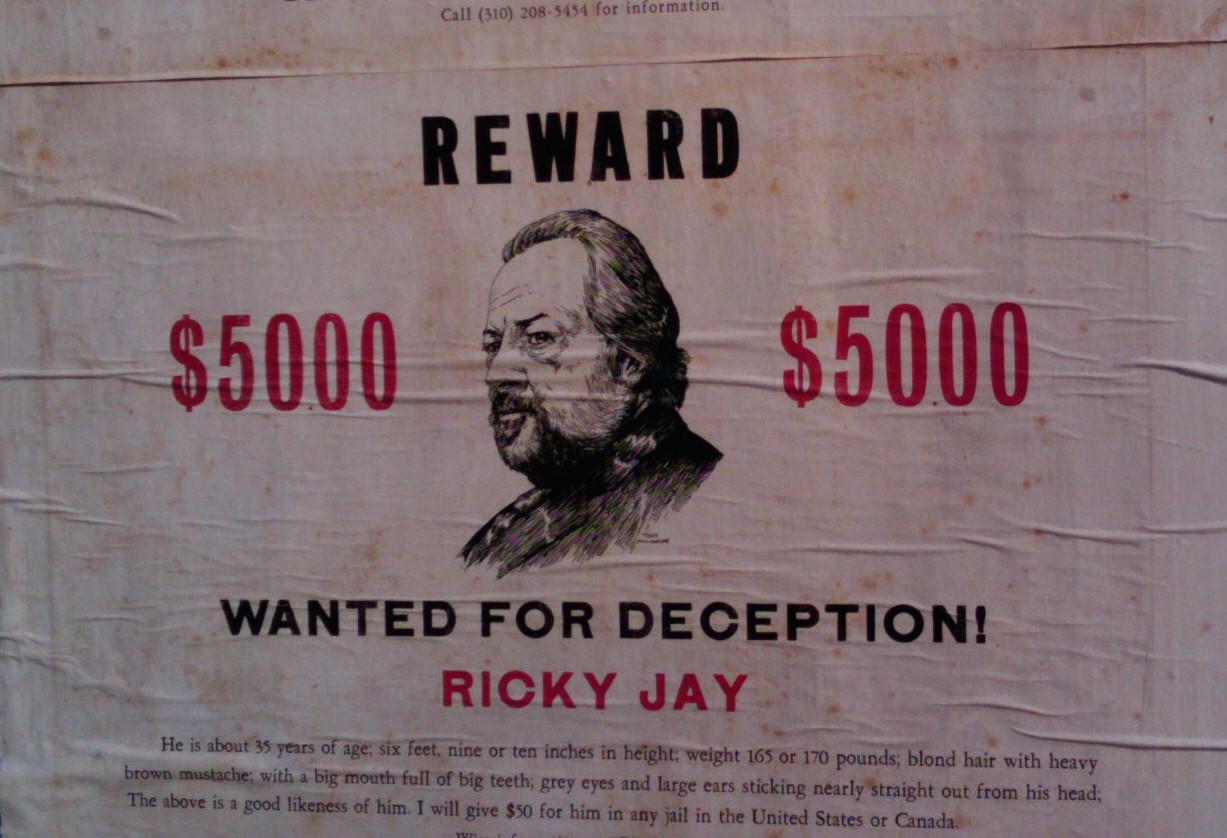

Header image: “Ricky Jay poster” by Ingrid Richter is licensed under CC BY 2.0

NO COMMENT