Despite access to shelters, some people experiencing homelessness still choose to live on the street.

On one of the wettest days in more than five years in Chicago, as rain poured in sheets from the sky and flooded the streets below, Raphael Mathis pushed his shopping cart through the mostly empty parking lots at Lake Shore Drive and Lawrence in hopes of finding a customer to offer his services.

“I can’t wash a car in the rain, but at least I’m trying to do something,” Mathis said. “I’m not knocking nobody for what they do, what their hustle is, but I’m just not one to stand up and really beg anyone.”

Mathis was a member of the “tent city” homeless community under the bridges of Lake Shore Drive in Uptown until mid-September, when the city initiated a 6-month construction project that forced the community to vacate the area. According to the Chicago Tribune, some residents of tent city declined offers to go to shelters in favor of staying on the street. Mathis is one of them.

“I tried the shelters — some are very unsanitary,” said Mathis, who has been on the street for six years. “Some of these people there have tuberculosis and don’t even know it. Some people have lice and bugs on them.”

Mathis is not alone in his weariness towards shelters; a 2017 survey conducted by the City of Chicago found that of the 5,657 homeless interviewed on a January night, 28 percent were unsheltered.

While Mathis pushed his cart through the parking lots, at the edge of the exit ramp of Lake Shore Drive and Foster Avenue stood Leroy Bass, panhandling with a plastic cup. Bass, 43, lives in a nursing home now but was homeless for seven years. Bass said he had both positive and negative experiences with shelters and understands why people fear them.

“A lot of these homeless shelters, they attract scum,” Bass said. “There are nice people out on the street, but there are people out here who are mentally crazy, and they don’t even know what they’re doing — and a lot of them go to the shelters. So a lot of people won’t bother with the shelters.”

Creating a Safe Environment

While Bass and Mathis endured the downpour, other homeless men filed into the Epworth United Methodist Church just blocks away down Kenmore Avenue. Cornerstone Community Outreach, a not-for-profit organization that manages several different shelters on the North Side, uses the space inside the church to shelter up to 70 men per night. Vince Stefanelli, the Men’s Homeless Shelter Director for Cornerstone, said he uses a tough, no-nonsense approach to create a safe environment.

“This is absolutely a safe shelter,” Stefanelli said. “Yeah, there’s a lot of shelters out there that are just — they’re vile. They’ll get thrown out if they don’t pray the right way with the right people in the morning, there are fights, people get stuff stolen— that’s not the case here.”

Stefanelli said the majority of the men in his shelter are in their mid to upper 50s, respect the rules and the space and want to avoid conflict. When someone does become a problem, the group works together to make sure the person leaves the shelter.

“I say, ‘hey, this is really easy as long as you follow these rules: no arguing, no fighting, keep your cell phone volume off, don’t come in here drunk, don’t come in here high — we’re not a flophouse,’” Stefanelli said.

In the Dead of Winter

According to the Chicago Tribune there were at least 26 cold-related deaths in Cook County last winter. Stefanelli said there is little difference in the atmosphere at his shelter between the winter months and summer months, because even on the coldest nights, they generally are forced to maintain their capacity of 70 men.

Jaimie Smith is a case manager and the Community Volunteer Coordinator with Franciscan Outreach, an organization that provides several shelter locations in Chicago. One of these shelters is the Franciscan House located at 2715 W Harrison St, which has a capacity of 257 beds — nearly four times that of the men’s shelter at the Epworth United Methodist Church. When the temperature falls below freezing, the Franciscan House will let in anybody who shows up at their door, no matter how many people are already inside.

Like Stefanelli, Smith said the Franciscan House works to battle the negative connotations associated with shelters and create a safe environment, but that it’s difficult with nearly 300 people and a limited amount of staff.

“We get a lot of people who will only come to the shelter in the winter, so it’s a lot more crowded,” said Smith, who used to work overnight at the Franciscan House.

“People who would normally sleep in tent cities, or just outside generally in parks—they’ll come and sleep at our shelter because they can’t sleep outside anymore. So that changes the dynamic—just how guests interact with each other. Then also, when there’s that many people in one space there tends to be a little more conflict that we have to monitor.”

Lack of Housing

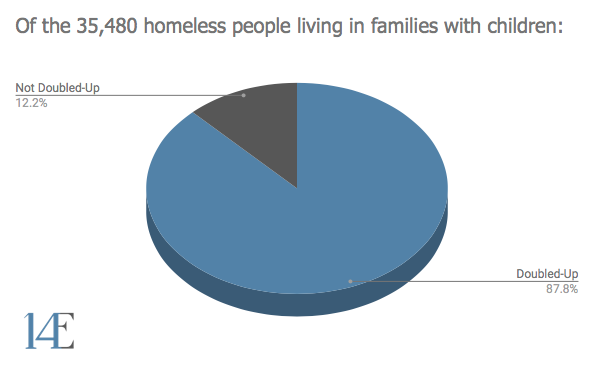

While the City of Chicago counted nearly 6,000 homeless this past January, the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless (CCH) uses data from the U.S census to include people who are temporarily living with friends or family in their count of the homeless population. Using this method, the CCH found that 82,212 people in Chicago experienced homelessness in 2015, and 82 percent of them were staying with friends or family rather than in shelters or on the street.

Source: Chicago Coalition for the Homeless .

Both Smith and Stefanelli agreed that even if the entire homeless population of Chicago was willing to take advantage of shelters, there is likely not enough space in the city to accommodate them. Smith said that one of the biggest challenges she faces in finding permanent solutions for the homeless is the lack of affordable housing and finding landlords to accept her clients as tenants.

“A lot of my clients have felonies, so they’re not getting housed because of that,” Smith said. “Addiction — a lot of landlords screen for addiction, things like that.”

Mathis, who still lives in his tent in the Uptown neighborhood despite fear of being harassed by the police, said he has been on a DCFS list for housing for four months. He said he has tried going through multiple organizations to find a permanent housing solution and finds the process exhausting. He said he will continue to live in his tent and avoid the shelters until he is able to find a long term housing solution.

Lack of Public Funding

Just before Christmas in 2016, a 72-bed homeless shelter run by North Side Housing and Supportive Services at 941 W Lawrence Ave was able to avoid closing its doors for good with a last minute donation. The shelter has since received additional donations raised by activists in the community and continues to operate. While this is a positive step for the community, it illustrates how hard it can be for shelters just to stay open, nevermind create a perfect environment that suits the needs of everybody on the street.

Smith said that at the Franciscan House does not receive very much funding; despite being the second largest shelter in the city and the largest that is publicly funded.

Stefanelli agreed that funding is an issue when it comes to providing proper shelter for the homeless. Though he understands some of the skepticism and stigmas associated with homeless shelters, he is committed to making sure his shelter does not fit the stereotypes that keep many of the homeless community living on the street.

“There’s never enough public funding. There’s no money in this, my college loans are head over heels — they want to drain me for every penny, and I can’t pay them,” Stefanelli said. “But I stay here and I do this because my boys need a safe shelter. But yeah, we need funding, just take a look around.”

Header image: “Late Snowfall” by Spablab is licensed under CC BY 2.0

NO COMMENT