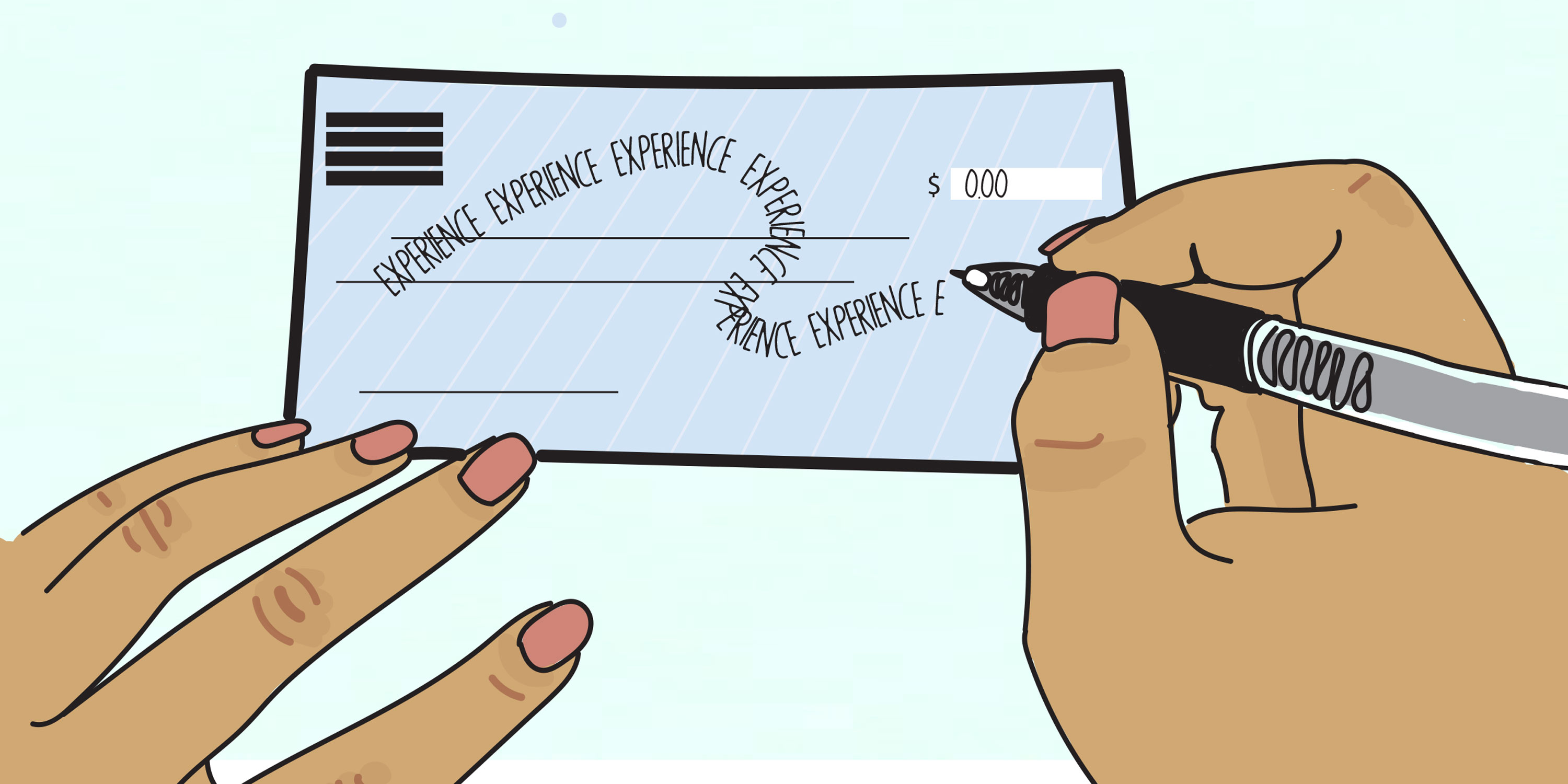

When resume blurbs are often treated like their own type of currency, many students find themselves feeling like they need to work for free

Olivia Bucciarelli, a fourth-year student at Wayne State University in Detroit, worked as the head supervisor at a children’s day camp this summer. The position paid well and she liked the hours, but it wasn’t exactly what she envisioned herself doing this summer.

Bucciarelli, who is majoring in public health, was hoping to gain valuable experience in her field over the summer, but felt forced to accept a position that is unrelated to her career goals due to her financial constraints.

“It’s really, really disheartening to find a field you’re really passionate about and then search for internships in that field and find they all want you to work for free,” said Bucciarelli. “I click the little filter that says ‘paid’ and literally all the positions disappear.”

Graphic by Katie Adams, 14 East.

To college students today, the pressure to stand out may feel as strong as their soul-crushing student debt. Peers often become competitors and appetites for success are becoming increasingly voracious.

Dr. James Wolfinger, a labor history expert at Illinois State University and former professor at DePaul University, noted that more high school students are pursuing secondary education than ever before in United States history. “This has put a lot of pressure on students because there are now a lot more students competing for jobs in this information and technology economy we have,” said Wolfinger.

Many students are looking to start building their resumes and portfolios in any way they can so they can stand out from the pack and ensure a safe and profitable future for themselves.

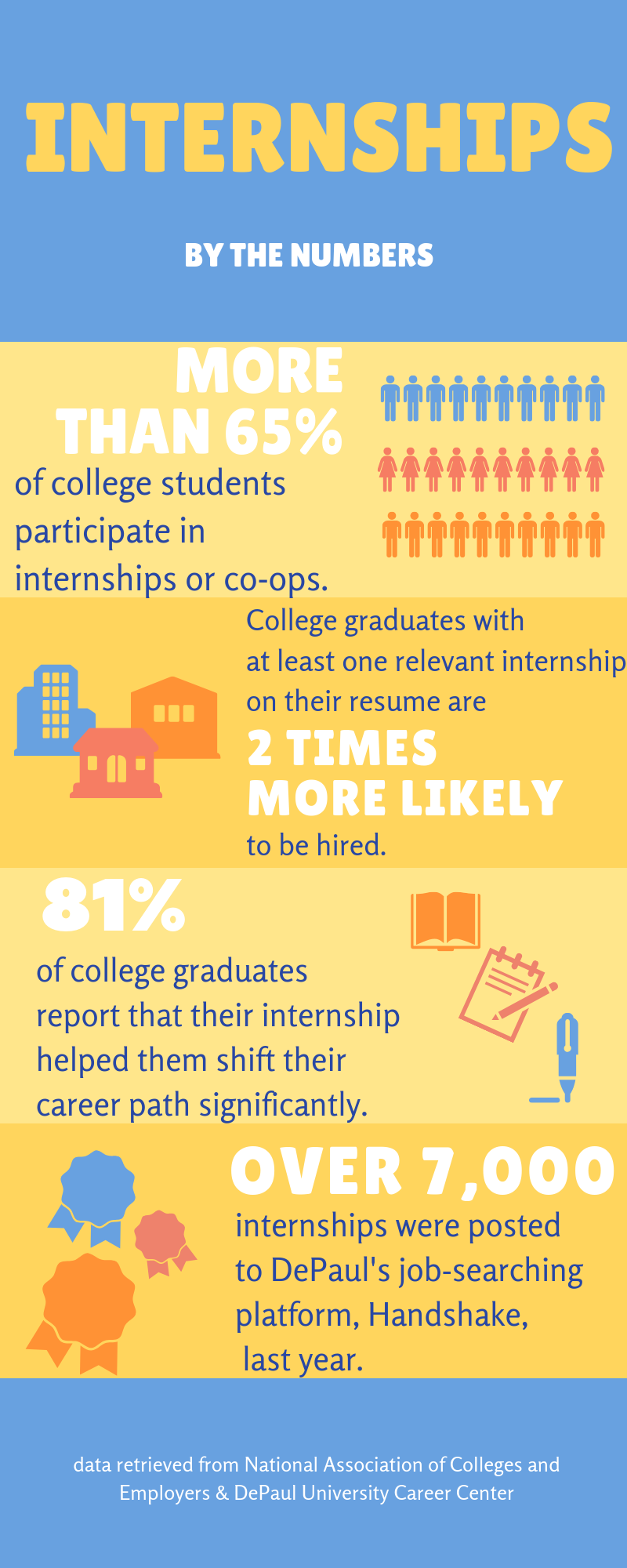

Employers are excited to see this level of eagerness in the country’s young people; they just aren’t showing it by opening up their pocketbooks. Over 1.5 million internship positions are filled annually in the United States, but many of the employees working at those positions did not receive financial compensation for that work.

Unpaid internships, though their predominance varies by field of interest, remain prevalent fixtures in American labor culture. Students and labor activists have spent time criticizing this trend and its questionable ethics, so the U.S. Labor Department came out with some new guidelines for employers looking to hire unpaid interns in January 2018.

However, these guidelines don’t do much for young workers. Instead, they end up making it easier for employers to offer unpaid internships by providing pretty loose standards to define an intern’s job as work that “complements” paid work rather than displaces it. The concept of hiring someone to work for no pay has been normalized as something young people do to grind and work their way up the ladder.

Bucciarelli is cognizant of that competitive culture among young professionals, and she has witnessed dozens of her peers work unpaid internships. “I have to pay rent. I know some people can afford to work 30 hours a week and not get paid for it, but that is not the reality of my situation at all,” said Bucciarelli.

She pointed out that she thinks there is a professional development system in place that rewards those with privilege and “it’s hard not to feel very jealous or angry.” She said that she has talked with some of her peers about her frustrations and they have agreed that those with financial security are much more able to accept positions that will give them valuable experience and connections, while young people without financial advantages are not afforded that opportunity.

Gia Zampardo, who will soon be graduating from DePaul with a degree in public relations and advertising, held an unpaid internship position that spanned about a full year and required her to work at least fifteen hours a week. She worked as the sole development and events intern at one of the country’s largest non-profit organizations.

Her tasks included grant writing, content copyediting, donor outreach, media promotion and event space booking, as well as working all events and assisting with cleanup. Zampardo also worked over twenty hours a week as a Whole Foods cashier and dog walker during her internship.

“I felt like I should have been paid for my work,” said Zampardo. “Frankly, I felt like my work was pretty on par with my manager’s work most of the time.”

Zampardo said she was given a $500 stipend after her 300th hour of unpaid work, which she was thankful for but felt was as a bit of an afterthought that followed her noticeably diligent work.

Graphic by Katie Adams, 14 East.

Paloma Ruiz, an English major at Northwestern University, went the unpaid-but-for-class-credit route and worked as an editorial intern at a Chicago-based literary magazine in the fall of 2018. She was not monetarily compensated for her work but was able to earn class credit that counts toward graduation.

“As an English major, I know I’m not in this to be practical or make a lot of money,” said Ruiz.

Ruiz’s position required her to commute to Chicago from Evanston three times a week to attend collaborative meetings, edit content, plan community outreach efforts and work on other assigned tasks.

“Honestly it was a very valuable experience, but that doesn’t mean that I think I shouldn’t have gotten paid. I think they had the budget to pay me and I worked just as hard as my coworkers who were salaried,” said Ruiz.

Though she wishes she had gotten paid, Ruiz believes her position helped familiarize herself with the kind of work she wants to do in the future. Karyn McCoy, the assistant vice president of DePaul’s Career Center, encourages young people — especially those pursuing careers in nonprofit, creative or governmental fields, who have much higher likelihoods of encountering unpaid internships — not to completely dismiss the prospect of an unpaid internship.

McCoy believes internships not only offer valuable experience, but also help students build a network of connections. Many universities, DePaul included, offer scholarship funds that students can apply to so they can support their unpaid internship, and negotiating pay with an employer is not entirely out of the question.

“All the research confirms that having two related experiences in your field, whether they are jobs or internships, will make you much more likely to be hired,” said McCoy.

Kyle Yang, a Columbia College student, worked as a graphic design intern for a small beverage company this year. He worked about 15 hours a week and his designs were regularly featured on the company’s website, social media posts and other promotional materials.

Yang felt he needed to take this position because he wants as much work as possible in his portfolio so that he can secure a job that pays well after graduation. Yang also shared that his manager would often require him to do tasks that were not outlined in the job description or aligned with his professional or personal goals, such as reception work.

“I kind of felt like once they had me there, they could do whatever they wanted with me,” said Yang.

If facing feelings of exploitation at their unpaid internship, McCoy encourages students to have an empathetic conversation with their employers. Explaining their situation to their boss can seem daunting to a young employee, but McCoy points out that many employers are unaware of the realities their interns face.

“Oftentimes, they don’t know what a double whammy it is to work for free and then also have to pay for a class for credit,” said McCoy. “They’re also sometimes unaware that their interns have to pay for transportation or work other jobs, so it’s worthwhile to let your boss know about these things.”

By encouraging these dialogues between interns and their employers, McCoy is hoping more young workers learn how to advocate for themselves. “Sometimes gaining the experience is really worth it, even if it requires a tough conversation or a tough decision,” said McCoy.

Header illustration by Natalie Wade, 14 East

Editor’s note: An erlier version of this story listed Dr. James Wolfinger as a current professor at DePaul. He currently a professor at Illinois State, and the story has been changed to reflect this.

NO COMMENT