“Logan Square is canceled,” I hear over the sound of ear-splitting and insufferable house music. Through the clouds of Juul smoke in the small basement apartment on California and Fullerton Avenue, I see the culprit. A mullet-clad mustached man wearing a beret, cut-off pants and camouflage Dr. Martens — canonically Logan Square.

To the evident distress of the mustached man — Hipster Logan is dying, replaced with a new stage of gentrification where young professionals garnish Milwaukee Avenue with condominiums, Divvy bikes and $15 pizza.

Discussion of Logan Square gentrification often feels like it’s been beaten with a stick. Defeatist rhetoric paints the process as an inevitable and unstoppable force, making it easy to dismiss responsibility when the battle seems already lost.

But this transformation isn’t over — changes in residents, businesses and property values are still affecting permanent and long-term residents. And though these changes seem recent to the artists/hipsters, they are the ones the Latinx community have been dealing with for decades.

According to census data, 19,200 Hispanic residents moved out of Logan Square between 2000 and 2014, making it the Chicago neighborhood that lost the most Hispanic residents during that period. The white population has seen a 47.6 percent increase, and as of 2017, the neighborhood’s white population has exceeded that of the Hispanic population.

In an interview with WBEZ, John Betancur, an urban planning professor at University of Illinois at Chicago, described Logan Square’s transformation from a hub of European immigrants in the ‘60s, to a lower-income Latinx community in the ‘80s when white residents moved to the suburbs. Through gentrification processes, the Logan Square/Avondale submarket is now experiencing a real estate boom that, between 2000 and 2018, witnessed a 168 percent increase in housing prices, compared to the city average of 71.6 percent, according to DePaul Institute for Housing Studies.

The term gentrification is used frequently and often carelessly, thrown around as a flippant justification for a new building or coffee shop, but the term was originally coined by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe changes she was seeing in London neighborhoods.

“One by one, many of the working class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle classes,” Glass wrote, “Once this process of ‘gentrification’ starts in a district it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working class occupiers are displaced, and the whole social character of the district is changed.”

Today, the process of gentrification is similar. Property values rise as developers deem an area profitable and real estate agents increase attraction to potential residents. Rents increase, displacing long term residents, and new demographics move in, pushing old communities to the backburner.

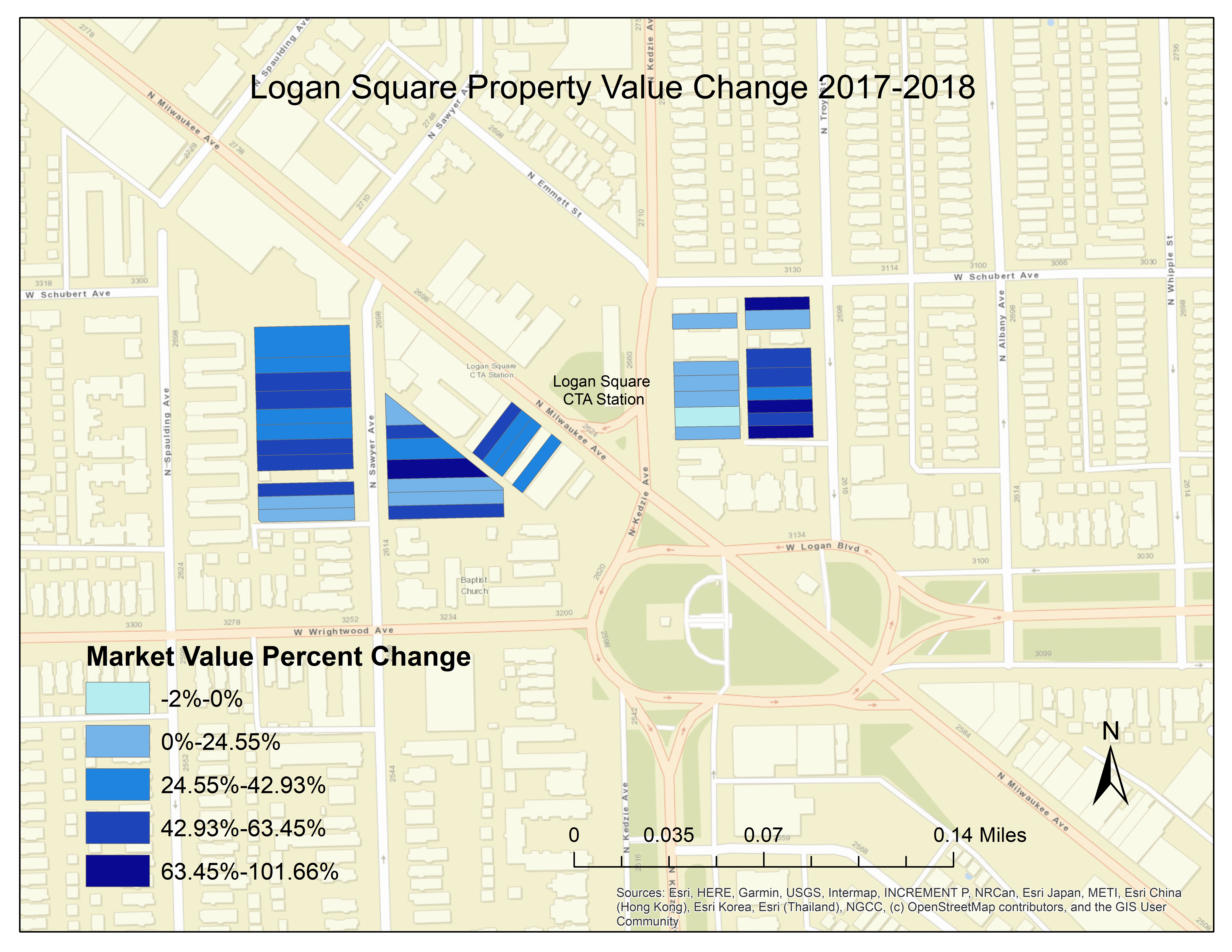

Map of property value increase in 2017-2018 in parcels around the Logan Square CTA station. Map by Patsy Newitt and Chris Silber. Data from Cook County Assessor’s Office.

DePaul students are players in this narrative, in a fabled sort of mass exodus out of Lakeview/ Lincoln Park their second or third year, with many renting in Logan Square.

the depaul flock migration to logan square is so gorgeous this time of year…..

— cockatrice lil squirt (@chuntaholic) August 25, 2018

Located in between the Lincoln Park and Loop campuses, the neighborhood is specifically convenient for DePaul students – 74/Fullerton bus to Lincoln Park and Blue Line to the Loop. “All of my friends moved here, so it seemed like the logical option,” said Madeline Hectus, DePaul student and Logan Square resident, on her move from Lakeview to Logan.

Students are one of the first groups to move into gentrifying neighborhoods because of lower rents and perceptions of what’s cool and trendy, according to Euan Hague, the director of the School of Public Service and a professor of geography at DePaul. And they enter these neighborhoods as renters with the intention of temporary residence, making it easy to ignore the community constructed by long-term and permanent residents.

I moved to Logan a little less than a year ago. The quick access to Puerto Rican food and Geneva, the cashier at the Walgreens on Fullerton and Kimball Avenue, who offers immeasurable verbal support for my outfits when I purchase Miller High Life, make it pretty easy to love. But the signs of gentrification, blared through an excess of craft beer and little free libraries, are difficult to ignore. It’s complicated to balance being a contributor to gentrification while also loving your neighborhood and community, specifically a community that was built years before I even stepped foot in Chicago.

This delicate balance brings up the question of whether it’s possible to move into these neighborhoods without damaging the communities that built them. What are ways that we, as students, can offer support?

An empty Unity Park in 1986. Photo by Hector Mojica, from Free Press and the Chicago Public Library.

Families gather in Unity Park in 2019, a popular community space for current Logan Square residents. Photo by Patsy Newitt, 14 East.

A 2017 piece by Tim Marklew for Culture Trip included Logan Square in its lineup of the best neighborhoods for college students. “Logan Square is a cool option,” Marklew wrote, “[With] a real sense of community fostered by its working-class roots.”

Looking at neighborhoods like Logan Square through the lens of what’s trendy is historically damaging (see Brooklyn or Wicker Park), and can easily overlook the impact of new residents.

“There’s this rhetoric that ‘we’re making communities better,’” said Arely Barrera, community leader at the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, LSNA. “But that usually just means whiter and more affluent.”

In Glass’s original definition of gentrification, she stresses that the displacement of lower-income residents distinguishes gentrification from development. According to the DePaul Institute for Housing Studies’ 2019 State of Rental Housing in Cook County, the Logan Square/Avondale area had a 12 percent decrease in the share of affordable units between 2012-2014 and 2015-2017, second only to Portage Park/Jefferson Park.

Ashley Galvan Ramos, 21-year-old constituent Services Liaison for Ald. La Spata (1st) and former youth leader at LSNA, knows this displacement well. Ramos grew up in Logan Square, as her family settled there after leaving Mexico in 1991. “The only time we would move was down the street,” she said. “It’s my home.”

In March of 2018, her landlord told her family they had 31 days to double the $800 rent of their apartment on Ridgeway and Wrightwood Avenue or move out. Those 31 days, she recalls, are blurred memories of urgency and panic.

“We could barely pay the rent already,” she said. “It was scary for a while because we didn’t know where we were going to live.”

The Ramos family jumped from household to household until they found a stable 4-bedroom in Austin, where rent was cheaper. Despite no longer living in Logan Square, Ramos remains involved with LSNA and plans to one day run for alderman of the 35th Ward. “Logan will always be my home,” she said. “No matter how high the rent gets.”

As families are displaced and new residents with the financial capacity to pay higher rents move in, public services are forced to adjust to the new affluent influx.

“With education, for example, we’ve seen a decrease in funding in our schools…because there are less students,” Barrera said. “People are moving out, and the people moving in aren’t [CPS] students.”

Because the CPS budget is partly based on the number of students, Logan Square public schools are struggling to keep up. “It impacts the students that are still remaining because they get resources taken away,” she said.

This new middle class audience, typically with a disposable income, brings a different expectation for economic and social structures, creating a disconnect between old and new residents. This dichotomy of old-and-new is often uncompromising, and efforts to bridge the gaps are few and far between.

“[The long-term residents] are concerned with things like a lack of crossing guards, or the lack of art teacher at the public school or the failure for trash pickup,” Hague said. “Students expect bars, cafes, coffee shops and event spaces…when the local bakery turns into a vape shop, this becomes a problem.”

The perception of restoration is initially welcomed, but it reaches a tipping point when the desires of the new residents outweigh the old. “There is a feeling of ‘I used to know everything that’s going on in this community and now I don’t even know where to get information about it, I’m just seeing the impact,’” Hague said.

Alessandra Rios, a DePaul student who grew up in Logan, watched the Pay-Half where she used to buy tank tops for $5 turn into the Dill Pickle Co-Op, an organic grocery co-op that sells peanut butter for $12. She now lives in Pilsen and describes Logan Square as a place she no longer knows.

“On top of not being able to afford the s—t that’s going on in your community, whether it’s entertainment, buying produce, or going out to eat, now you’re not seeing anyone that looks like you,” she said, “And you’re saying, ‘Why would I go to that place doesn’t cater to me?’”

Dill Pickle Co-Op at 2746 N. Milwaukee Ave. in 2019. The co-op opened in 2009, replacing Pay-Half, an inexpensive women’s clothing store. Photo by Patsy Newitt, 14 East.

“You stop going there because you become jaded,” Rios said. “[New residents] have these mindsets of spending money on chucheria – nothingness – stuff that we don’t care about and we really can’t afford. What was once ours is no longer ours.”

Rios remembers the Logan Theatre, which has transformed into an upscale destination with movie trivia nights, comedy open mics and a prolific bar and lounge, as a haven of $4 tickets and movies in Spanish. “Sure, it had rats running around, but the movies were cheap and provided for residents who weren’t able to enjoy movies in English.”

Historic Logan Theatre at the center of Logan Square on Milwaukee Avenue, 2019. Photo by Patsy Newitt, 14 East.

Changes like these denigrate the social fabric of the previous community. Residents lose the security and comfort of what they formerly called home.

“Students who are first generation already feel like ‘you’re not from here you’re not from there,’ and then the community that you were a part of changes,” Barrera said. “A lot of students were feeling like strangers in their communities… It gives the feeling that our youth aren’t safe and they are the problem.”

Ramos found changes in neighbor-to-neighbor communication specifically contributed to her loss of home.

Growing up, Ramos’s neighbors were integrated into her everyday life with active communication. “There were always tons of kids playing outside, and there were family members sitting on porches watching all the kids no matter if they were their kids or not,” Ramos said.

“Slowly the kids started moving out, and more college students and lawyer-type people started moving in,” she said. This translated into a distinct shift in Ramos’s interactions with new neighbors.

“They wouldn’t open their doors to anyone,” she said. “That sense of community that we had started going away.”

When talking to old and long-term residents, there seems to be an overarching lack of acknowledgment and awareness by those moving in, whether that be through supporting local businesses, talking to neighbors or even simple recognition.

Paying attention to communities, and listening and interacting with voices that were there before, Ramos proposes, can help bridge the gap between old and new.

Hague specifies this awareness. “Find out what time school lets out and don’t park in front of it,” he said. “Find out the times of the church services and know that driving along the street on Easter Sunday is going to be congested.”

“Don’t assume that your presence by definition is better than what was there before, it’s just different than what was there before,” Hague said.

There’s also a power in understanding the importance of where to shop.

Rios’s aunt used to own a shoe store called Pump Room, which has since closed, where she would sell scarves and jewelry she picked up in her travels at a price affordable for her community “It’s unfortunate that people aren’t willing to spend money to places like that – to businesses that may not have the caliber of product they’re looking for, but give them the money so they can achieve that caliber,” Rios said.

Choosing to shop somewhere out of convenience or trendiness limits the capacity of smaller businesses to succeed. “There’s this Pinot’s Palette bullshit where you paint and drink wine for so much money,” Rios said, “Like why can’t you go to the Puerto Rican artist alignment. Go to stuff like that.”

Barrera suggests political action and a direct address of the inequalities that bolster these changes. “I think it’s always difficult to talk about privilege…But that’s the first step,” she said.

Action isn’t limited to spending money and talking to neighbors. Acknowledging privilege and subsequently using political power through voting and supporting non-profits like LSNA can also be a means to advocate for displaced groups.

Logan Square residents discussing 100–unit affordable housing complex on Emmett Street near Logan Square Blue Line station, 2019. Photo by Mina Bloom, courtesy of Block Club Chicago.

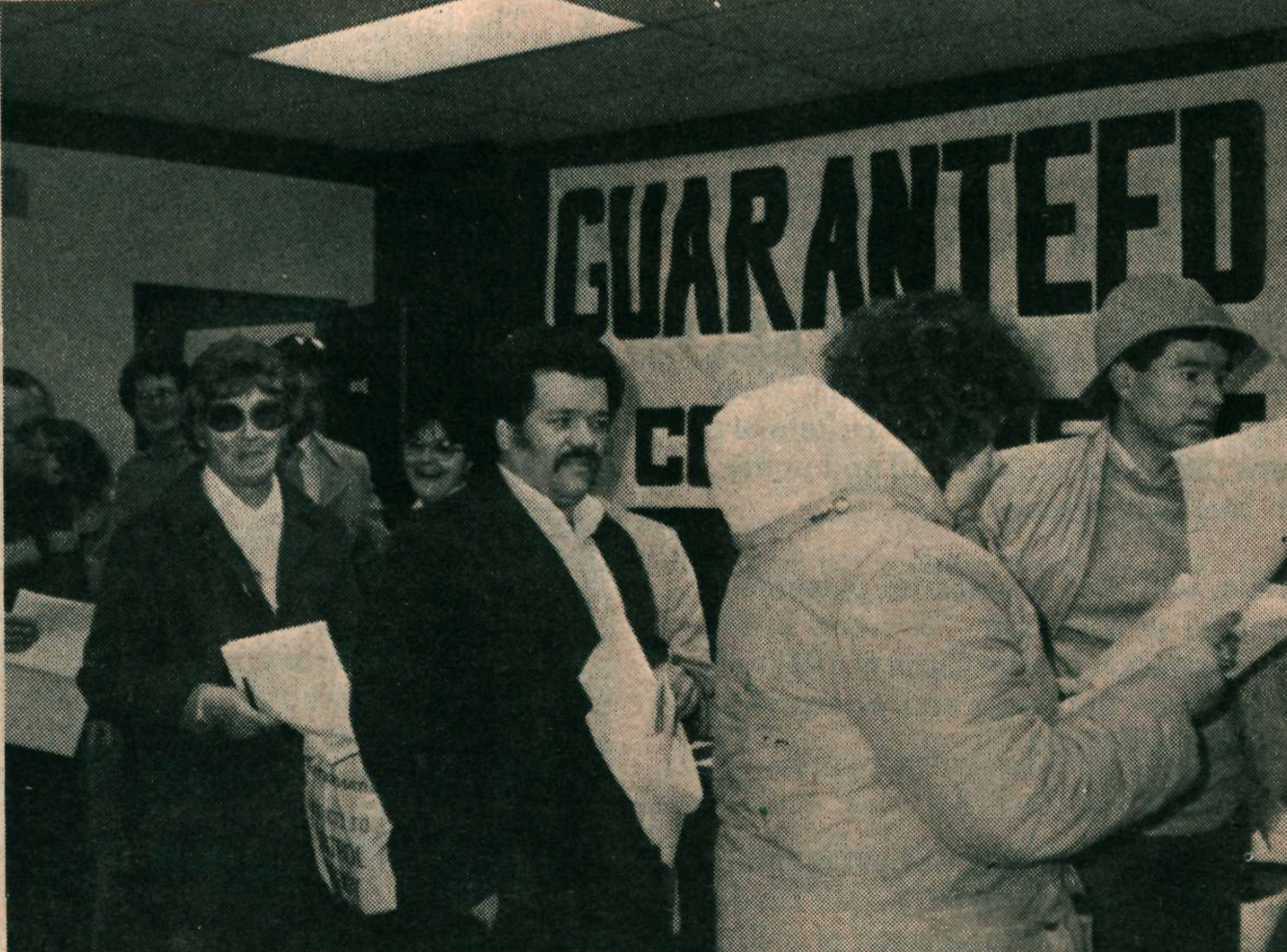

Members of the Northwest Neighborhood Association in 1987 gathering signatures for a non-binding referendum concerning home equity insurance. Photo by Ben Joravsky, from Free Press and the Chicago Public Library.

Regardless of how many Carlos Ramirez-Rosas we elect as alderman, these issues exist, have existed and will continue to exist in some capacity as cities develop. “One of the critical things to remember is that your generation is not the first to do it, and you won’t be the last,” Hague said.

Mustached man exists in perpetuity. He’s not the first jaded hipster lamenting the death of a neighborhood, and there will surely be more to come.

Though I’m not under the impression that we can single-handedly stop gentrification, old residents prove there are ways we can do better.

Reject the notion that the damage is done. Be cognizant of our role in these changing neighborhoods. Work to protect these communities and the individuals that have worked to build them. Don’t let “Logan Square is canceled” be the end of the story.

Iconic Logan Square monument in the middle of the square, 2019. Photo by Patsy Newitt, 14 East.

Header Image by Patsy Newitt, 14 East

NO COMMENT