This piece was aired at 14 East’s virtual live storytelling event on the theme of wilderness in May.

Corpus Christi, Texas. It’s close to New Year’s Day 1990, and Collette Robertson goes home with a guy from a rock band. Keith Russell Judd. Their tryst was never anything more than a bit of fun, except that it made me. He was long gone by the time I had a name, which was originally “Austin Axl Robertson” after the lead singer from Guns N’ Roses.

I mean, really, “Austin Axl”? Thanks for changing your mind, mom. I would have looked terrible in a mullet.

Since Keith and his band were always on the road, my mom wasn’t able to get word to him that he had a son. So the next time they toured through Corpus Christi, Texas, she brought me along to see him. The band was at their hotel, and Keith was in the pool. My mom handed me over to him, and I cried immediately — not something I had a habit of doing, actually. I was usually a mellow baby.

My mom didn’t push him to make a decision. Maybe she was expecting him to voluntarily accept his fatherly responsibilities, but he didn’t. A few months later, she reached out again. My mom found out where he was and called the hotel. She told me she was not well received. Apparently he said to my mom, “You’ll find someone else and marry him. And he’ll be the kid’s dad.”

Keith shirked his responsibility to me, and he forsook the possibility of a relationship with me. The thing is, that’s par for the course in my family. My mom grew up without her father, a man named A. T. Vines, short for Alexander Tyrone. He and my grandmother divorced before my mom could remember anything, and he moved constantly throughout my mom’s childhood — often without telling anybody. If she wanted a relationship with him, most of the time it was up to her to track him down first.

In fact, my mom didn’t find parental nurturing from either of her birth parents. She soon had a brother, Alex, when she was about three. At that age, she was already forced to do most of the mothering. She changed her brother’s cloth diapers regularly, even though she had only recently graduated from diapers herself. It didn’t always go well, either: she still vividly remembers accidentally stabbing all the way through Alex’s thigh with a diaper pin once.

So my mom was brought into the world by two absent parents. But guess what? Neither of them — my mom’s parents, my grandparents — knew their fathers. A.T. was sired by a man named John Henry (of the “give me liberty or give me death” Patrick Henry lineage). They never met. My mom’s mom, Rita Mearlene Tope, was fathered by Emerson Mearle Tope, who also left to avoid being a dad.

So Keith was simply the most recent iteration in a vicious cycle of fatherly rejection.

As a kid, I didn’t really know I was missing anything. Hell, maybe I wasn’t. I felt loved. My mom raised me with the help of her mother and grandparents. She waited tables, she went to school, and she nurtured me.

And when I was four, she met my dad. Not my biological father; my real dad.

Terry Glenn Phillips, Jr., or Glenn — his dad is Terry. He looked like a lankier Alan Jackson, down to the matching black Roper cowboy boots and Stetson hat. Glenn welded for a living on the U.S.S. Lexington in Corpus Christi. A mutual friend set my mom up with him, and the sparks flew instantly.

A year later my sister CarLee was born, and the year after that my mom and my dad married. We soon moved from Texas to Alabama, where dad’s family lived — and where a promising job lay waiting for him.

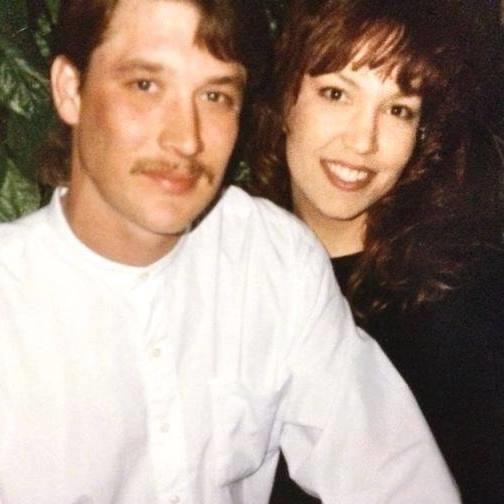

Collette and Glenn around the time they got Married

Things were good. We were indisputably poor, living in an old single-wide trailer and unable to afford wrapping paper or a tree for Christmas, but things were good in my mind. I had a silly dad who played Street Fighter with me. He kicked my ass mercilessly, and I loved it. I tried so hard to beat him, I rubbed blisters into my fingers. I soon had a brother, Terry Glenn Phillips III (call him Trey).

Around this time, my genetic father, Keith, had reached some major turning points in his life. A true rocker, he had indulged in psychedelics for years. But by the late nineties, Keith was dropping acid daily — sometimes whole sheets.

Experts will tell you: consuming psychedelics at this level can exacerbate mental disorders a person might already have. Some believe really high amounts can even produce mental disorders in someone who’s never had them before.

Keith went off the deep end. His brother, my uncle Monty, still remembers the day he thinks it happened. They were all in the studio, recording, and it was Keith’s turn to lay down his bass tracks. Everyone sat behind the soundboard, listening and studying the sound levels. It was going great.

Then Monty looked up. He saw Keith openly sobbing. He never missed a note — tears streaming down his face, he recorded the track perfectly. Everyone knew something was wrong, but they didn’t know what to do about it.

A couple years later in 1997, a now-unstable Keith Judd wanted to get back at his ex-wife who he believed stole money from him. So he grabbed four postcards, and on each one he wrote a single word: “Return. Money. Or. Dead.” He sent them to her work address, along with a semen-stained Playboy magazine with a knife tucked inside, and a copy of his father’s military discharge papers.

Since he also signed his name on each postcard, it didn’t take long to catch him. In 1999, Keith was convicted and sentenced to nearly ten years in prison.

Around this time, the man who raised my mom — technically her grandfather, my great-grandfather (though TECHNICALLY technically he’s my step great-grandfather) — but regardless, the only true father figure my mom ever knew —came to live near us in Alabama, since his health was failing.

Paw-paw Robertson, “grand-daddy” to my mom, died on Christmas morning of the year 2000.

These are the beginning of the dark years. My mom and dad screamed at each other all the time, and since the arguments started in private, I couldn’t figure out why. I just knew the anger that defined my life. One night, my mom came into the bedroom I shared with my brother and sister. She quietly opened the door, tiptoed over the disgusting mess of toys that obscured all but slivers of floor, and leaned over my top bunk to hug me tight.

“I love you, Marcus,” she said. “You’re my best one.”

That statement, the one she said before she left us, replays in my head any time I’m not occupied by an active thought.

I hid how crushed I was. Already denied a relationship with my birth father, I silently laid in bed while my only constant in life, my mom, walked out the door. Like Keith, she was gone. And Keith never tried to come back, but after four days, my mom did.

Apparently my dad got his shit together enough for her liking. They made up, renewed their commitments to each other, and we started going to church. For a while.

By the time things got bad again, I was old enough to pick up what was really happening. Dad was back to his old ways: spending whole nights in the bathroom adjacent to his and mom’s bedroom; playing Mortal Kombat for days at a time; tearing through the bank account, leaving nothing for groceries or bills; passing out on the couch, sprawled out in his underwear, drooling.

If we tried to wake him up and get him to bed, it sometimes took five attempts to rouse him. Anything he said to us came out incoherent, slurred mumbling. He’d sometimes sleep for 24 hours straight. Our back yard started to look like a junkyard. Tires, scrap metal and coaxial cables everywhere. Dilapidated pickup trucks.

My dad wasn’t just addicted to crystal meth — he cooked it in the bathroom. He’d lock himself in there, cook up enough to get himself blitzed and chain smoke cigarettes. If we were lucky, that’s all he’d do. I remember one time I wasn’t so lucky.

It was summer break, and I was in between eighth and ninth grade. I was watching Mythbusters, when mom yelled, “Glenn, I need that rolling pin! Soon!”

She sometimes made lavish, artful cakes for people. Mostly a hobby, but she was good enough to turn it into a business. So she did — “Collette’s Cakes.”

Mom had accepted a commission for a wedding, but her rolling pin snapped that day. So she asked dad to go pick up a new one at Wal-Mart, but he refused.

“I’m not gonna spend money on a brand new rolling pin when I know where I can get a perfectly good one,” he said, pointing into the woods behind our house. She relented: as long as she had a working rolling pin before sunset, she could finish this cake on time.

Dad enlisted my help.

We trekked through the woods, probably two miles. I had no idea where we were going until a collapsed cabin came into view. Dad and I climbed down into it, all the floors rotted through except for the basement. We rummaged through the dirt, leaves, broken planks and rusty nails for hours. Everything recognizable looked to be made 50 years ago.

Eventually we found that rolling pin, wholly submerged in mud. The wood looked dark from filth and moisture-rot. I knew there was no way in hell this thing could be used to prepare food. Dad looked pleased with our efforts, but he kept rooted around a while longer, looking for anything valuable.

Night fell on our way back home. Mom, already on edge, took one look at the rolling pin. She grabbed my dad by the arm, pulled him into their bedroom, and tore him five new assholes. The fight spilled back out into the living room. My mom, furious tears streaming down, dropped all pretense.

“You have got to get clean, Terry Glenn Phillips, or I swear to God I will divorce you and take these kids away forever.”

I have whole tomes worth of those stories. Like the time when dad dragged me with him to a huge pile of discarded plastic and metal, excitedly telling me we’d be rich if I could help him put together his invention — a pontoon boat with a glass bottom — from this assorted garbage. Or the time he told me he’d made a scientific discovery: a new species of invisible insect that lived inside skin, all over his body.

Meanwhile, my genetic father kept himself occupied while in prison. Some inmates work out, read, or take classes. Keith Judd picked a different pastime: he ran for president of the United States. Having already run for mayor of Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1993 and 1997, Keith decided to set his sights higher while in prison. So, in 2008, he filed for presidential candidacy.

Materials from Keith Judd’s campaign for Mayor of Albuquerque. Photo by Marcus Robertson.

As you’d imagine, he didn’t get much traction. So, in 2012, he tried again.

Cut back to me: I had just finished boot camp for the Air Force, and I was stationed in Texas to finish my training. One day, I leave my room in the barracks to go grab something at the chow hall. I’m walking into the common area, heading for the exit door. I glance up at the TV, then I double-take.

I see my father’s mugshot filling the whole frame, with a Fox News chyron reading, “Federal inmate challenges Obama in WV.” Keith Russell Judd won 41 percent of the vote in West Virginia’s Democratic primary.

I was dumbfounded. I told everyone to look up. “That’s my dad!” I said. I felt a strange pride in this man, this father I had neither met nor spoken to. From then on, I started telling all of my friends. I even managed to grab some campaign swag from my uncle Monty. (show picture) I’d recount this tale countless times, to the point that his story became part of mine.

Three years later, we spoke for the first time.

Still in the Air Force, I was deployed to the deserts of the Arab Emirates. Keith told my mom and his brother Monty that he wanted to talk to me. The idea felt daunting to me, far too much to handle while I was working 17-hour days, seven days a week, in support of combat missions half a world away. So I told my mom to let him know I was interested, but to hold off until I made it back to the States.

He ignored her. He found me on Facebook and sent me messages, often with links to fringe political conspiracy articles. I didn’t know how to respond, so I simply didn’t. He knew I wanted to wait before we opened a dialogue, so I put off dealing with him.

But he kept on. Eventually, his frustration won out. He sent me long messages, accusing me of getting close to his brother — again, my uncle Monty, whom I had come to love — only to sow discord and pit them against each other.

Finally, I responded. “You were told to wait until I was done with my deployment. I have gone 25 years without a single word from you, so you will wait until I am damn good and ready to speak to you.”

That’s the last thing either of us said to each other. Five years ago, our first interaction was our last. He’s a free man now, and my uncle tells me he’s doing much better than when I was deployed. He has a job, and he has his own place in Albuquerque near Monty.

My real dad, the one who raised me, is a coal miner and a preacher now. Terry Glenn Phillips, Jr. got clean, turned his life around, and found lasting redemption in the church. He never had to quit being my dad. The ghosts of his past never leave him, though: as many times as my siblings and I have tried, we can’t get our parents to sit through an episode of “Breaking Bad.” They tell us it refreshes the worst moments in both of their lives. It’s too painful.

As bad as Glenn’s flaws were, I love him. He’s a good dad. He made terrible mistakes that may have permanently scarred me and my siblings, but he tried. He was there.

I don’t know if I’ll have kids, but I do know I want to break this vicious cycle. I will not be the latest generation in an unbroken line of skittish sperm donors. In fact, I’m going to break the cycle whether I become a dad or not.

I’m driving to Albuquerque right now to meet my birth father, perennial presidential candidate Keith Judd, for the first time. I have no idea what I’m going to say.

If you or someone you know is experiencing substance misuse, you can call the Alcohol & Drug Abuse Action Helpline at 1(800) 662-4357. You can also visit Drug-Free America’s website to learn more about drugs, treatment and online screenings.

If you are a DePaul student and are experiencing substance misuse, the University’s Office of Health Promotion and Wellness has a variety of educational programs and support groups.

NO COMMENT