“We must remember that our people and stories are not just moments that should be glorified resilience, but that those conditions placed upon them are from capitalist and imperialist powers that still affect our people and personal experiences today.”

The October calendar is filled with both conventional and unconventional holidays — Mean Girls’ Day on the 3rd, the end of Hispanic Heritage Month on the 15th and Halloween on the 31st.

But if you’re Filipino, that calendar might look even busier with lumpia-filled boodle fights to attend and tinikling workshops to attempt, because October is Filipino American History Month.

Once you’ve satisfied those culinary cravings and creative juices, it’s time to venture off and explore the myriad of ways to celebrate the never-ending journey and discovery that is Filipino American history.

In October 2009, the U.S. Congress officially recognized October as Filipino American History Month. However, the fight to establish the month-long observance began in 1992 with husband-and-wife duo Fred Cordova and Dorothy Cordova bringing awareness to the role of Filipinos in U.S. history.

The Filipino presence in the U.S. existed for centuries prior to this. The earliest recorded presence was on October 18, 1587, during the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade era. Spanish conquistador Pedro de Unamuno worked with Indigenous Filipino sailors and embarked on a trip to what is now Morro Bay, California.

As of 2019, there are an estimated 4.2 million Filipinos living in the U.S, and Pew Research Center reported how Filipinos are the third-largest Asian origin group — next to those coming from China and India.

To commemorate efforts of the older generations and mobilize younger ones, the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) named this year’s theme “50 Years Since the First Young Filipino People’s Far West Convention.” This convention brought together over 300 young Filipino American activists at Seattle University in 1971. It was coordinated by the Cordovas and Anthony Ogilvie, who wanted to make space for young Filipino Americans to network and organize.

This annual set of conferences from 1971 to 1982 put Filipino issues to the forefront of the political conversation — ranging from discrimination in academia to the plight of the manongs of the United Farm Workers movement.

A year after the first convention, then-president Ferdinand Marcos declared the Philippines under martial law. This became a prevalent topic, not just for convention attendees, but in every Filipino household.

Fr. Primo Racimo commemorates FAHM through storytelling — paying special attention to stories of resistance and countering falsehoods of the past especially during the time of martial law.

“During the martial law days, from Aparri to Mindanao, particularly during dinnertime,parents and grandparents [would] tell the story of how good Marcos is. That storytelling was left in the consciousness and unconsciousness of those little kids before.This was never countered seriously. And now we are paying the price [because] they are back,” Racimo noted, as children and grandchildren of Marcos are running for office.

“We must remember that our people and stories are not just moments that should be glorified resilience, but that those conditions placed upon them are from capitalist and imperialist powers that still affect our people and personal experiences today.”

Racimo is a priest in the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago and Iglesia Filipina Independiente (more commonly known as the Aglipayan Church.) Through his role, he finds a way to intertwine relevant Philippine issues like immigrant rights and elections in his sermons.

“Even in my sermons, I really speak about going out to vote,” Racimo said. “It’s our duty to exercise our faith in the public arena.”

Racimo plans on practicing what he preaches. He will be voting for the first time since 1981 in the upcoming May 2022 Philippine elections. For four decades, he wasn’t as inclined to vote even though he was eligible. After seeing the impact of current president Rodrigo Duterte’s “failed promises” on Philippine society, Racimo thinks the time to vote is now.

Vying for the presidency in 2016, then-candidate Duterte pegged himself as an iron fist who was ready to clean up the country’s messes — like what he did in Davao City where he served as mayor for 22 years. Combining his unabashed language, machismo character and daring promises, Duterte who started as a maverick, won with 16.6 million votes.

The daring promises mentioned in his campaign included ending corruption, defending Philippine borders against China and ending the spread of distribution of illegal drugs during his first term once elected.

“But after six months [of being elected], he began to not do the things he promised,” Racimo said. “My experiences with the elections in the Philippines … it’s like a suitor coming to [give you] the moon, but when it comes to reality, those promises are not there.”

On October 20, the Department of Justice (DOJ) released a matrix of 52 deaths during police anti-drug operations in the country. The war on drugs, which is estimated to have killed over six thousand civilians, dates back to Duterte’s first year as president in 2016. The crackdown on drugs gained both national and international coverage from journalists like 2021 Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa and groups like the United Nations and the International Criminal Court.

With a diverse and star-studded presidential lineup, voters are expectant to how the next president will overhaul the country’s drug distribution.

“As I’ve matured in politics, I’ve come to realize that I have to vote for a person who is closer to what the ideal is,” Racimo said. “Be patient because this election is very, very crucial.”

Mari Roy, an ethnic studies junior at University of Washington Tacoma, sees FAHM as an “everyday thing” to celebrate. Not just in October.

This month, they continued to be active in various organizing spaces such as the Northwest Filipino American Student Alliance, Seattle chapter of Anakbayan and Pi Nu Iota, a Filipinx-interest sisterhood at the University of Washington and Seattle University.

Similar to Racimo, Roy keeps on stirring up conversation about what it means to be Filipino in the U.S.

“We must keep the dialogue going as much as we are celebrating,” Roy wrote in an email. “We must remember that our people and stories are not just moments that should be glorified resilience, but that those conditions placed upon them are from capitalist and imperialist powers that still affect our people and personal experiences today.”

At DePaul University, social chair Adora Alava has been working with the rest of the KALAHI (DePaul’s Filipino student organization) executive board to strengthen community ties among students within the diaspora.

“We kickstarted [FAHM] with a speed dating activity and established a pamilya (family) system for more people to get to know each other,” Alava said.

Alava is also the Student Government Association’s executive vice president for diversity and equity. Through her roles, she plans on collaborating with other cultural organizations to strengthen allyship.

On October 21, KALAHI co-sponsored an event with the APIDA (Asian Pacific Islander Desi American) cultural center and Latinx cultural center entitled “Oral Stories of Revolutionary Care.” It was a storytelling workshop led by Lily Be and Olola Ann Zamora Olib about how caring and advocating for ourselves nurtures community care and healing.

Although Filipino American History Month is coming to an end, reasons to celebrate are found in our communities everyday. However we choose to pay homage, Racimo believes in the power of coming together to share.

Share food. Share resources. Share stories — struggles included.

“We should not do this alone,” Racimo said. “We should be in solidarity with other ethnic groups, we need their solidarity to us and [they need] our solidarity to them.”

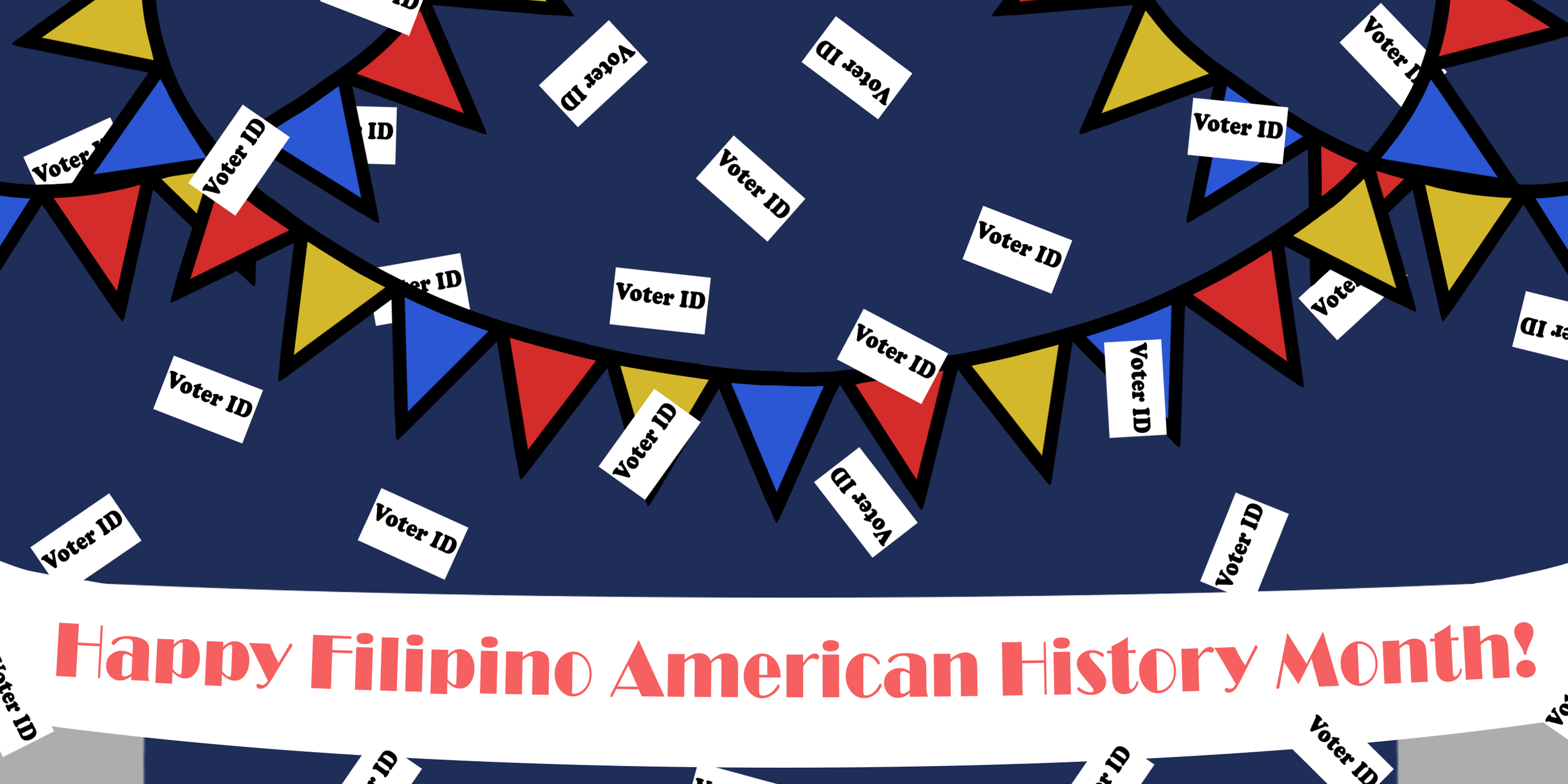

Header image by Samarah Nasir

NO COMMENT