The pandemic is shifting the way we grieve our loved ones — something that undocumented immigrants have already been forced to do.

The world has been covered in a blanket of grief. The New York Times dedicated its front page on May 24, 2020, to the names of the nearly 100,000 U.S. victims of the pandemic. It’s been 22 months — almost two years since the first reported COVID-19 case in the country — and the total to date now exceeds more than 733,000 deaths. Suddenly, many are forced to experience grief from a distance.

At the height of the pandemic in Illinois, 4,212 people died in December of 2020, making it the deadliest month in the state. Pedro Antonio died in Chicago on December 10, 2020.

“My dad was in the hospital for about three weeks. He was admitted on Thanksgiving Day,” says Pedro Antonio Jr.

His entire family was infected. In the same emergency room was Antonio Jr.’s sister, Vanessa Antonio, intubated just down the hall from her dad. Vanessa would later recover.

“We kept in communication via text and FaceTime calls with nurses at the hospital, but once my dad was intubated, which was week two, we couldn’t really have any more communication because he was completely sedated,” says Antonio Jr.

For Antonio Jr. and his family, they thought Antonio would prevail. His condition however, would rapidly deteriorate; his kidneys began to fail, pneumonia hit, his blood pressure began to drop and he fell deaf.

On December 9, Antonio’s family scheduled a FaceTime call for December 10 from their home in Brighton Park to Saint Anthony Hospital, roughly three miles away.

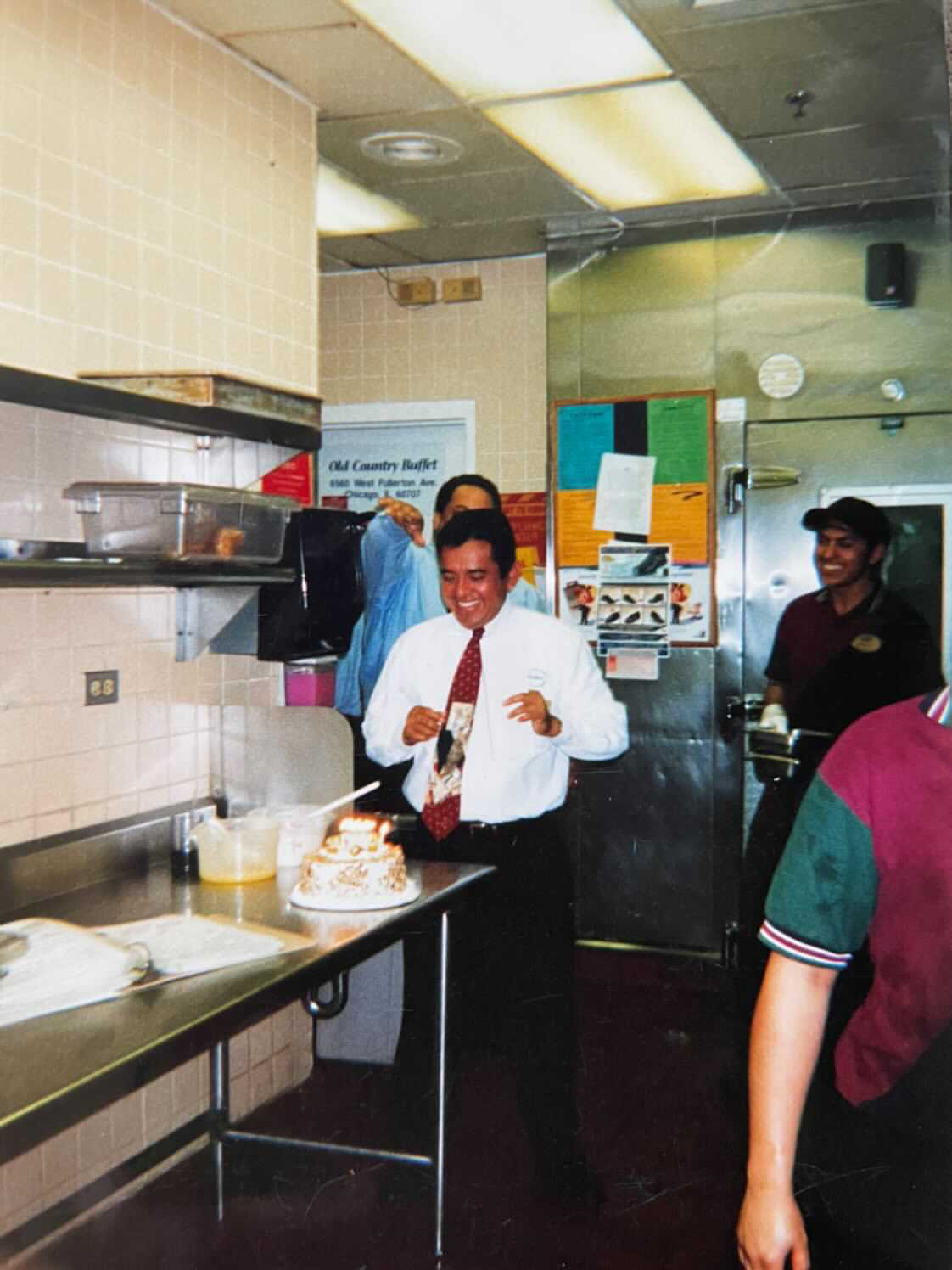

Pedro Antonio celebrated his birthday with co-workers at Old Country Buffet in 2006. Photo courtesy of the Antonio family.

“All of a sudden the nurses announced that he had passed away and it was pretty devastating because since she was speaking in English, me and my siblings, we understood right away. But my mom had no idea what was happening for a couple of seconds,” says Antonio Jr..

Antonio Jr. had to translate for his mom that his dad had just died.

“Watching your father, not even realizing that your father was dead on a FaceTime call was just so dehumanizing,” said Antonio Jr.

Through an iPad, FaceTime, Zoom and phone calls, thousands have said goodbye to their loved one.

For Suzette Brito and her family, a phone call informed them that their uncle was murdered while he was closing his store in Mexico City.

“Everyone was crying on the phone and I was like, ‘What the f–k is going [on]?’ And my mom drops the phone and starts screaming,” says Brito.

Brito recalls August 28, 2020, the day her uncle, Rodolfo Ramirez, died, being something out of a nightmare.

“They tried to, you know, do the chest compressions, but he had taken too many gunshots, he had lost so much blood already. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.”

The news sent panic across the family. Some booked immediate flights to Mexico from Chicago. Others did not have that option. Jose Luis, the oldest of Ramirez’s children and the only one living in the U.S., could not board a plane due to his immigration status in the country.

Jose Luis has four children, and leaving them and his wife to attend funeral arrangements in Mexico meant the possibility of not being able to return back to the U.S.

Family and friends convinced Jose to stay.

“It was really painful to see, because nothing you tell him can fix the pain that they’re feeling. No one prepared him, prepares you for when you lose a parent and the fact that he couldn’t say goodbye,” says Brito.

Jose Luis immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico when he was 18 years old. Now 36, he had not seen his dad since then.

To cope with the loss, Jose Luis and family members mirrored what was happening in Mexico. A nine-day prayer began leading up to the last day that would conclude with an ofrenda.

Ramirez was laid to rest in the family’s hometown, La Hacienda Oculixtlahuacan, in the Mexican state of Guerrero. Because they were in rural lands, the families could only communicate through phone calls.

Brito updated her cousin Jose every day before prayer on what was happening across the border, almost 2,100 miles away.

Family members celebrate Rodolfo Ramirez’s one year death anniversary by creating an ofrenda. Picture courtesy of the Ramirez Family.

Brito said on the last day of the prayer everyone that came into the space brought offerings.

“They bring bread, they bring candles, they bring flowers and the entire altar is covered in all these garments. It’s honestly really beautiful.”

A wooden cross was specially made containing Ramirez’s name, date of birth and death. The tradition is for the wooden cross to be gifted from someone close to the family. In this instance, the wooden cross was not only gifted to the family in Mexico, but also one to Jose Luis in Chicago.

“It was his best friend that [gifted the cross] for him here. When that moment happened, it was really heartbreaking because he literally hugged it as if it was his dad and he wouldn’t let go of it.”

For decades, grieving from a distance has been one of the most traumatic events for undocumented immigrants.

248 undocumented Mexican immigrants participated in a 2019 study conducted at Rice University, 85% of the participants experienced a transnational death and were more than twice as likely to meet the criteria for psychological distress compared to those who did not experience it.

“It’s so impersonal when you have to participate in Zoom. Same thing with undocumented or documented individuals that want to travel to their native country … because you’re not able to do the thing you’re so accustomed to doing, it creates more stress,” says Sharika House, a therapist who specializes in grief, stress and depression.

House explains a significant uptick in grieving clients who are now dealing with high levels of stress, anxiety and panic attacks because the traditional way of saying goodbye to the dead has been stripped.

“COVID really revamped the way we grieve, the way we process, the way we encounter grief, and so individuals didn’t know how to respond,” says House.

Months after Ramirez’s death, Jose Luis commissioned his father’s favorite local Mexican musical group to craft a song in his honor. The song narrates the life of Ramirez and brings comfort to the family members who didn’t get a chance at the usual goodbye.

For Antonio Jr, he found consolation in finally being able to touch his dad after his body had been sanitized for the funeral.

Header Image by Teagan Baker

NO COMMENT