DePaul students who frequent the Student Center dining hall are keenly aware of the conveyor belt that collects their used dishware and cutlery. But what happens to our leftovers after the dishes travel down the line?

This year, DePaul updated a dining hall program, Waste Not 2.0, that seeks to minimize and analyze the waste of college students who — according to the National Resource Defense Council (NRDC) and Bon Appéit Management Company — consume twice the amount of food on average as a corporate consumer.

However, the prevailing issue that is food waste is not new, or only applicable to college students.

The Impacts of Food Waste

According to the Illinois Landfill Capacity Report of 2019, 20 percent of the 19 million tons of trash thrown into landfills was food waste. Food discarded from homes and businesses in Illinois impact the atmosphere detrimentally.

In fact, the EPA reports that while the methane gas that is produced from human activity accounts for only 10 percent of the greenhouse gases admitted in the U.S. in 2019, its comparative impact is 25 times greater than carbon dioxide waste over a 100-year period. The food that is thrown into the landfills is one of these human activities that emit methane into our atmosphere

This means that the spoiled food that was thrown out of your fridge last week is actually more harmful than you could ever imagine. As a waste product, food is incredibly toxic.

Despite this massive amount of waste, Chicagoans are still going hungry. The Illinois EPA reports one in nine Illinoisans are food insecure. So uneaten food is being discarded, yet there are people in our community that face food insecurity. There seems to be a disconnect on how we see production and consumption of food.

DePaul’s Latest in Food Sustainability Efforts

Waste Not 2.0 strives to understand this disconnect and how DePaul students consume food and distribute its waste while analyzing the process as a whole.

DePaul has gone through a series of transformations in its waste management. Sean Gordon, Chartwells resident district manager, explains what happens behind the kitchen doors at DePaul’s cafe.

“In 2017, we had ‘Trim Tracks,’ which essentially did the same thing, but did not break anything into robust categories. This later turned into ‘Waste Not,’” Gordon said.

“Waste Not” furthered DePaul’s efforts in minimizing food waste by measuring leftovers in a clear quart container at the end of each serving period. In production, waste is considered things like the end of cucumbers or the top of an onion.

These containers were then analyzed by category. “[Waste Not] in its original form was tracking production overproduction, and expired [food],” Gordon said.

Production is expected waste that can’t be used like the top of a cucumber. Overproduction is food that is never scooped out of pans or thrown away.

Larry Rogers, Chartwells’ campus executive chef, has several responsibilities in the program, one of which is planning the menu and adjusting accordingly based on different types of waste.

“I am in charge of forecasting menus, the do’s and the don’ts, the pantry, the inventory, and the management of ‘Waste Not,’” Rogers said.

Rogers prepared these menus after the waste was calculated, but noticed the process was flawed. Rogers said that the amount of waste wasn’t predictable because it was measured and done at the end of the day, which took up a lot of time.

“It was just a natural evolution and technology has caught up, it’s a more user friendly way that we can track it. We can see where our waste is coming from,” Gordon said.

Over the summer of 2021, Chartwells began the process of implementing “Waste Not 2.0.” It included major updates to the existing kitchen system with waste now tracked through an iPad. No longer will waste be scooped from the pan into a measurable quart container. A user will be able to input how much waste is left in the same container it is served in. This tracking is immediate and in the moment.

“We are getting exact amounts because we can give measurements despite whatever container [is] used,” Gordon added. “It’s [tracked] more in the moment, saving a lot of time.”

Dirty dishes with excess food run on a conveyor belt to the kitchen for waste to be measured and analyzed (Hailey Bosek for 14 East).

This way, Gordon said it is quicker and easier to see what food is being eaten, what is overproduced and what is going to expire without having to remove the food out of any of its original containers to be measured. Now food waste can be inputted into the iPad system immediately instead of at the end of the day.

The iPad allows all of this to occur in the kitchen during the serving periods, thus saving time, and allowing workers to spend less time and effort scooping food into different measurement containers.

There are two major factors that are vital to the success of “Waste Not 2.0.” One of them is the kitchen and the staff.

“Everyone does a fantastic job especially at DePaul, [staff] are very aware of the process and very efficient about the tracking of it,” Gordon said.

Student Awareness

Despite the successful implementation of Waste Not 2.0 by DePaul workers, students may not understand how their decisions play a role in food waste management.

“It is a partnership between our guest and themself,” Rogers said. “Be aware of the waste that is contributing to landfills and what that does to the environment.”

When asked about the program, Molly Martindale, a freshman at DePaul, had no clue what happened to the food leftover on her plate.

“I go to the dining hall almost every day, but I never knew that there was a program that tracked it; I figured they just threw it all away,” Martindale said.

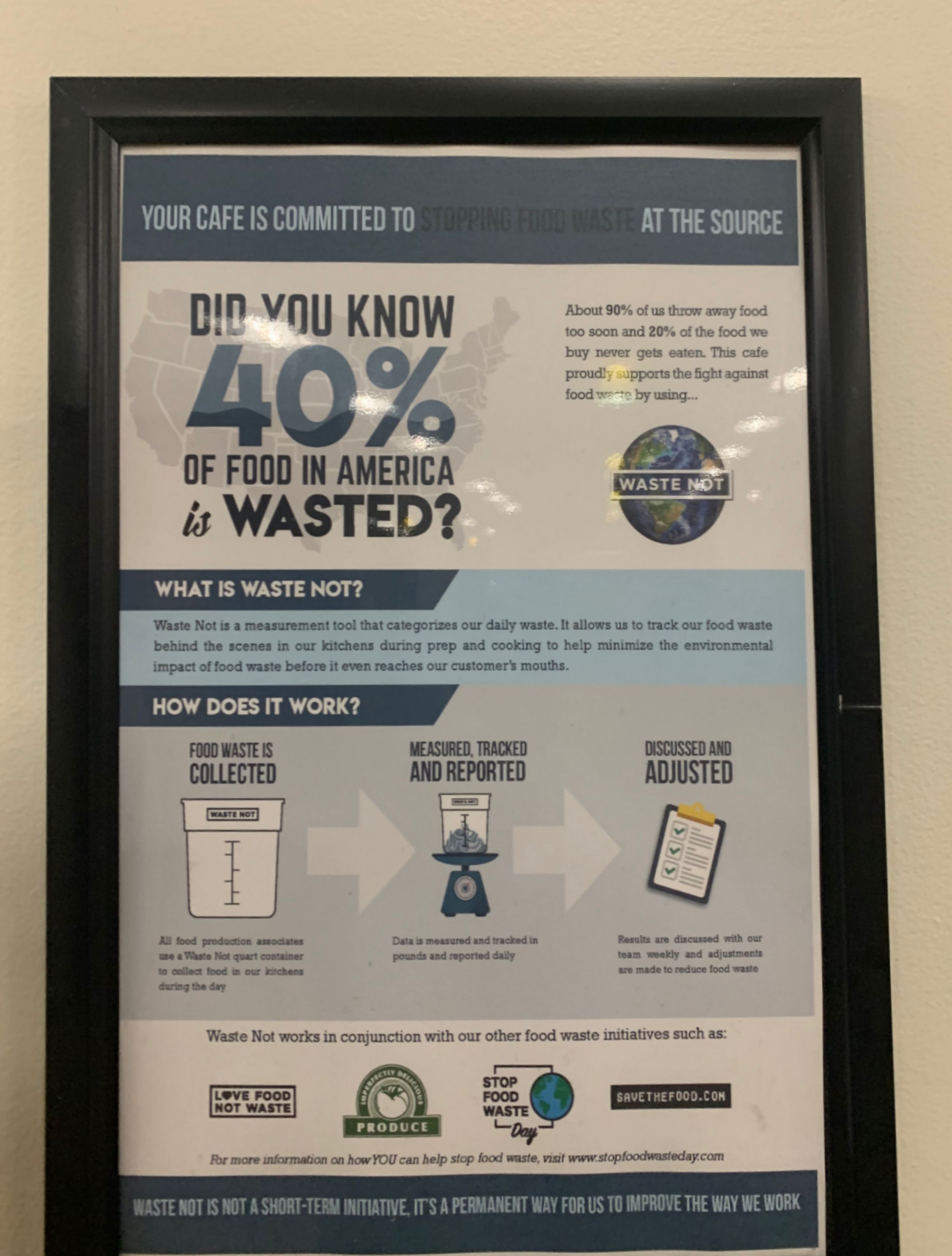

This isn’t an uncommon experience. There’s little information on the Chartwells program available to students besides the poster that hangs next to the conveyor belt of dirty dishes.

Above are two signs that hang next to the dishware conveyor belt in DePaul’s Lincoln Park Student Center (Hailey Bosek for 14 East).

In fact, a 2016 Food and Health Survey conducted by The International Food Information Council, found approximately one-third of Americans don’t believe they create any food waste.

While the kitchen can do everything right, a large part of minimizing food waste is student awareness. If no one knows it’s a problem in the first place, there is no initiative to find a solution.

Gordon sees this as a huge factor contributing to the waste problem on campuses, and plans to bring student awareness to the forefront of the “Waste Not 2.0” agenda. Gordon said a plan is in the works to communicate more about the program but didn’t share specifics.

According to NRDC’s study, college students end up wasting 112 pounds per person per year of food. A contributing factor of this could be the “all you can eat” format of many college dining halls. Instead of paying to order food, and bringing unfinished food home or throwing it away, college students load their plate up with things they want to try, or think they will finish, instead of waiting in line individually each time to get more food.

Gordon agreed with this reasoning based on his experience working for Chartwells.

“What I found on DePaul and previous campuses is that students load up a huge plate, but they only eat a little bit and the rest of it is wasted, out of sight, out of mind,” Gordon said.

Gordon explained that in many cases, students go throughout the line and grab without thinking. There is a lack of awareness to try to reduce the waste. He hopes that an increased amount of communication can help end this.

“Just to be aware that you can have as much as you want but not to just pile it all up only to waste it,” Rogers said.

The Systemic Origins of U.S. Food Waste

While the average consumer takes part in producing food waste, the root problem of global emissions and climate change stems largely from global corporations that have stakes in oil and other emissions. Another NRDC study found the top 15 U.S. food and beverage companies, like Kellogg’s and Coca Cola, generate nearly 630 million metric tons of greenhouse gases every year.

It also reported that this group of only 15 companies is a bigger emitter of greenhouse gases than the entire country of Australia.

Herein lies the cruel irony of food insecurity. Perfectly good food is wasted rather than properly managed. It is a frustrating realization that rather than spending the resources to properly outsource food, it is thrown out.

It is crucial that communities are made aware of this issue. Community awareness allows for a better and more localized understanding of where unused food can be reallocated. Rogers mentioned that part of his responsibilities include connecting with the local soup kitchen to help lessen local food insecurity.

Food waste is a nuanced issue with frustrations and ironies littered throughout. The first step is understanding and being aware of the issues. Students and staff alike can appreciate the constant evolution and strive to make DePaul a greener campus.

Header image by Teagan Baker

NO COMMENT