A look at memory and placemaking.

This piece contains interactive audio that is integral to the story. Press play when directed.

I find myself often connecting memory with physical locations – with places. My stomach knots up whenever I drive past my old apartment, a place with which I associate a lot of negative memories and in contrast, I feel a sense of relief whenever I go to Loyola Beach, a spot on Chicago’s lakefront that is often frequented but not crowded, a place I have often found peace and assurance.

I remember the specific memories, places and feelings that inspired my first-ever written story years ago. It feels only fitting that now, over 16 years later, in the last days of my undergraduate degree, I include some of the people who inspired my first written work: my family.

I wanted to know how members of my family associate memory and place. How we are similar in our memory-making and how we are different. How place ties us to our past and in turn, how it informs our future.

The Science of Memory and Place

Believe it or not but there’s a science to the relationship between memory and placemaking.

Memories that are strictly tied to a time, place or event fall into the category of episodic memory.

The concept of episodic memory was first created in 1972 by Canadian experimental psychologist Endel Tulving. He identified mental time travel as one of the main properties of episodic memory.

The idea of transporting oneself back in time was expanded upon in 2014 when a group of psychologists referred to episodic memory as a “remote control for the brain.”

Episodic memory includes the recall of specific events, specifically where and when something happened. A type of episodic memory is flashbulb memory, “a highly vivid and detailed ‘snapshot’ of a moment in which a consequential, surprising and emotionally arousing piece of news was learned.”

I don’t remember 9/11, I was just 48 hours shy of turning two years old, but it’s a prime example of flashbulb memory. A question I’ve heard asked many times is, “Where were you when the towers fell?”

My grandma was with me at the playground when she got a call from my dad. My sister was in her 3rd-grade class when her teacher announced the news to the room full of 8-year-olds. Everyone who had developed the ability to retain memory can tell you where they were that day.

Similarly, in March 2022, two years after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the 14 East staff compiled a collection of memories of the days when we realized that the world was shutting down.

All the memories are sharp and distinct. Everyone could easily recount where they were and what they were feeling like we hit a rewind button and transported ourselves back in time.

I wrote about the moment when I realized I was going to be getting kicked out of my resident assistant apartment, and frantic at the idea of having to leave Chicago, called my family who lives in Chicago and I asked if I could move in with them.

I still remember it like it was yesterday.

Best to Let Them Lie

My grandma is someone with whom I often associate the relationship between memory and place.

Some of the clearest memories of my childhood are with my grandma. Our walks in the park near her house where she told me stories of her childhood in the one and only Plymouth, IN, getting chocolates and riding the carousel at the mall, stories from her extensive travels. Sitting on the back deck of her home, looking out for specific birds with her and my grandpa, whispering in her ear towards the end of dinner time, asking her if I could slip away to watch Disney Channel on her bed.

The list goes on. That’s one of the reasons I wanted her to be a part of this.

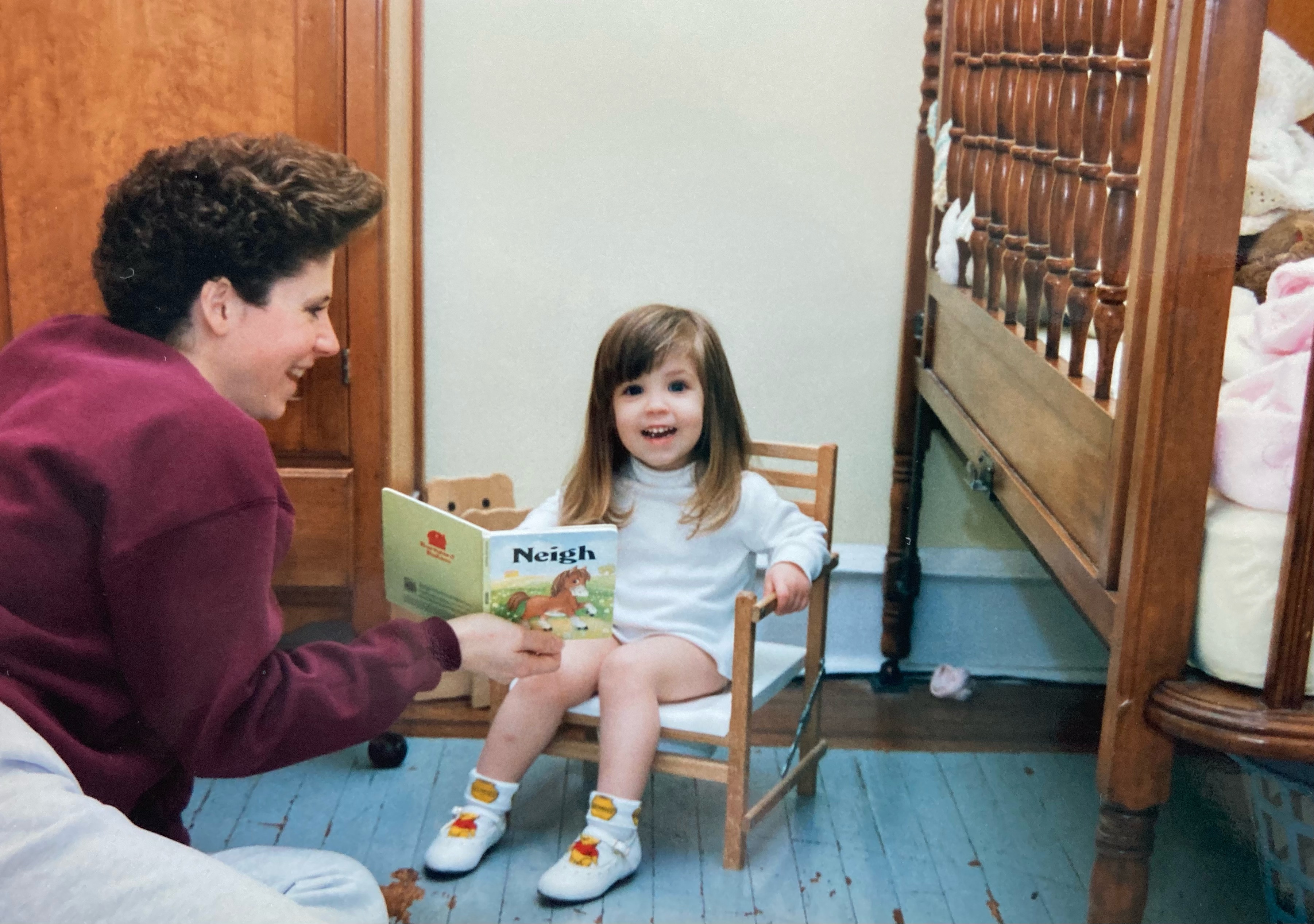

Grace’s grandma circa 1993. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

The other reason is my grandmother’s place-based recall. She describes places in detail, and recites the good and bad memories that stem from them with clarity.

My grandma considers her memories with discernment. While she values nostalgia, she doesn’t depend on it. In part, it’s because she can’t.

While she likes to return to places where she created good memories, she rarely if ever finds the opportunity to do so. Other places simply are no longer in existence or have completely changed, unrecognizable from how she remembered them.

“Were I to return they would conjure up healthy, wonderful memories, but it is what it is, we move on in life,” she said.

“Life is full of journeys. It’s not good to be so bound up with nostalgia that one cannot move ahead.”

Press play to hear from Grace’s Grandma:

While she may not get the opportunity to visit places where she has good memories, she doesn’t visit those with bad ones either.

“Bad memories can be very tricky. You can look at them and say, I’ve come a long way, I’m not the same person I was,” said my grandma.

Grace’s grandma (left) and mom (right) circa 1994. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

“One just has to judge whether a bad memory enables you to think about how much progress you’ve made as an individual,” she said. “Or whether there’s so much trauma involved that it’s best to just leave it alone and move on.”

Memories Have Their Place In the Past

Like my grandma, my mom is discerning of the roles different memories play in her life. The way she views her association between memory and place has changed over time. When she was younger, her memories were more tied to place, now, they’re more defined by who she spends time within those places.

Grace’s mom (left) and Grace’s sister (right) circa 1994. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

She doesn’t often cling to nostalgia and believes memory’s place is in the past and that’s where it belongs. “We can’t go back,” she says. “And I don’t want to go back in time. But I’m grateful for good memories, that they carry me through difficult times.”

Press play to hear from Grace’s Mom:

In the summer of 2013, my mom was diagnosed with colon cancer. For months doctors had thought it was other things, pulled muscles, a slowly rupturing appendix, but not cancer.

So when her doctor told her she had a malignant tumor, she was in shock. All of my family members remember the moment they heard the news – the flashbulb. News no one really wants to hear.

I had just gotten off the bus after returning home from a week away at soccer camp in the Pennsylvania mountains. When I left, I was under the impression that my mom was having surgery for appendicitis. Upon my dad picking me up after the bus ride back to the city, he informed me that was no longer the case.

I pressed myself up against the window of the passenger seat in my dad’s 2008 Honda Civic SI, driving south on I-76 towards the hospital where my mom had spent the last week. My gaze fixed firmly on the road ahead of me.

“It’s okay to cry,” said my dad, his tone leveled and even, nearly absent of emotion.

“I’m not crying,” I croaked back at him, but my voice was thick with choked back sobs.

It’s not a period of time my mom, or anyone in my family looks back at with fondness. But there are some places that carry bad memories that my mom can’t avoid. Her annual visits to her oncologist’s office bring dread and worry even though she finished her last round of chemotherapy eight years ago.

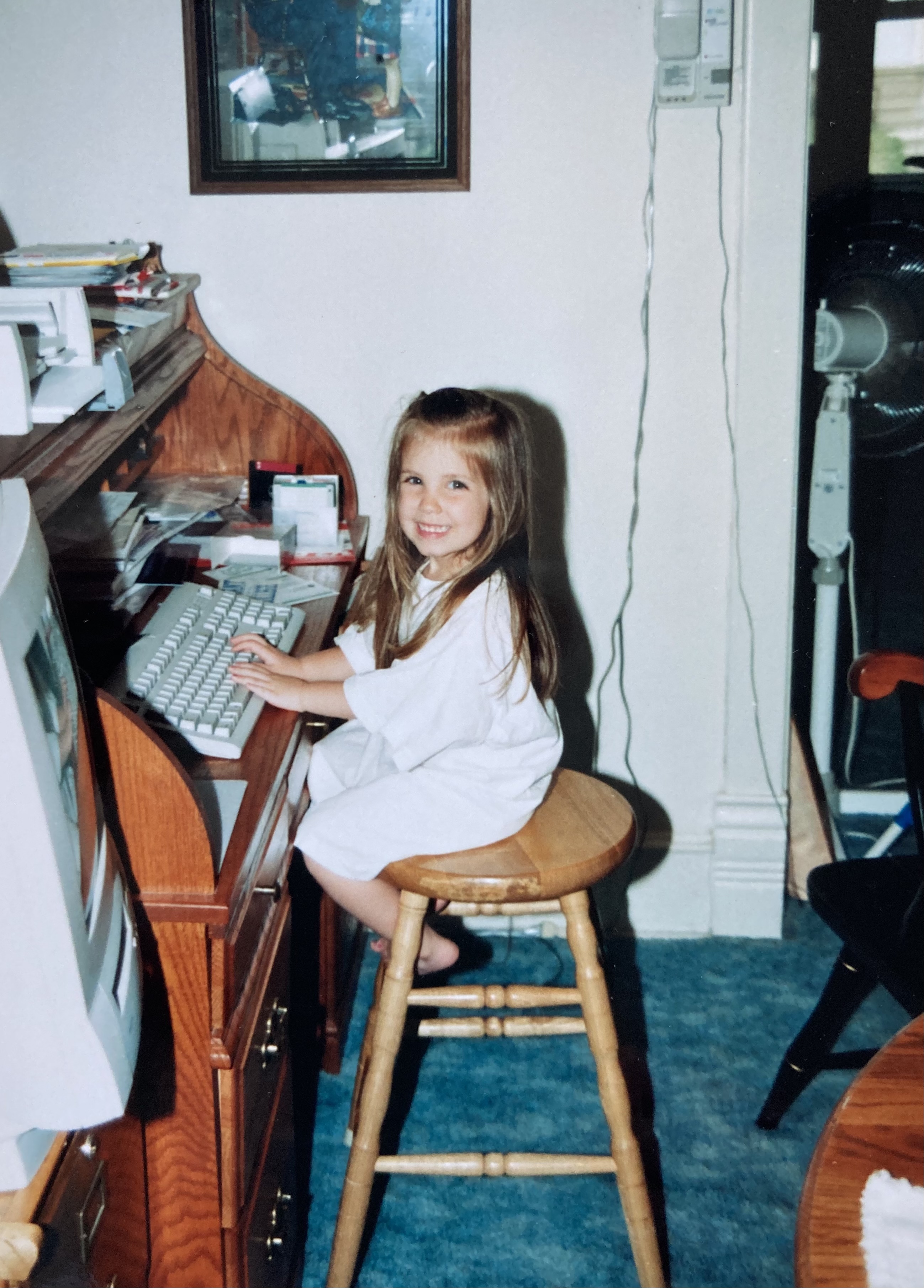

Grace’s mom (left) and Grace (right) circa 2006. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

But she prioritizes using her own painful memories to help other people navigate theirs. Even if it means returning to places she would rather avoid.

Press play to hear from Grace’s mom:

Loss, Nostalgia and the Reclamation of Memories

The memory of loss has the uncanny ability to transport us.

My sister’s memory is unlike any other. She can recall memories from a very early age in vivid detail. If you ask her about a certain point in time, she can tell you where she was, who she was with and exactly how she felt about it. She pulls no punches.

She loves her memories and she is deeply nostalgic.

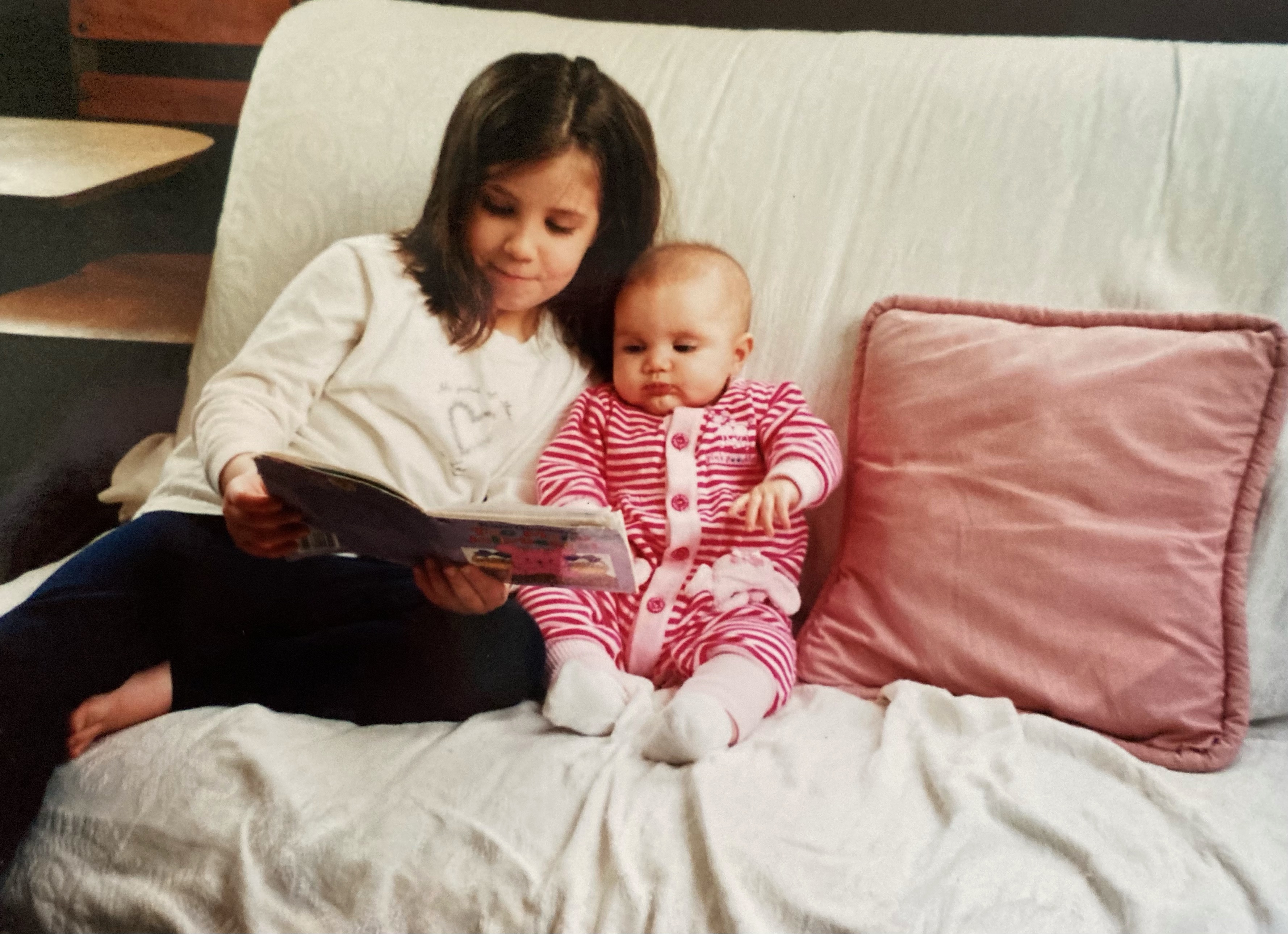

Grace’s mom (left) and sister (right) circa 1996. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

She doesn’t let bad memories dictate whether or not she returns to places where she created them. To her, most bad memories can be matched or overtaken by a good one.

“I don’t relive what happened there,” she says. “I just have the ability to remember.”

Had a terrible experience with an ex-partner at one of her favorite restaurants? She’ll take her husband there and they’ll laugh about it and create a new one.

My sister defies bad memories in the holy name of nostalgia.

Not every painful memory is as easily replaced, but it can be softened.

Our hometown of Philadelphia where she still resides today is a primary source of good and bad memories for her. She in a way, reclaims bad ones in an act of defiance – something she’s never been short on. And some bad memories take extra work to balance out.

Grace’s sister circa 1998. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

Especially those of loss.

Our cousin Ben died suddenly on July 15, 2008. It sent a violent ripple through our extended and immediate family.

In the years leading up to his death, Ben had spent some pivotal moments with our family. One of them over Christmas and New Year’s Eve, the other during the summer.

After his death, all she and everyone else had to hold onto were those moments, those last conversations.

The last time she spoke to Ben was when he visited Philly during the summer of 2007. On his last night there, the two of them sat together on the front porch of our childhood home as a radiant, otherworldly sun began to set. Neither of them had ever seen a sunset like that – especially not in North Philly.

Ben was extremely well-traveled for having just recently entered his twenties, he had seen sunsets all over the world, but he was awestruck by the breathtaking sunset that lowered itself upon North Philly that evening.

“You know the thing about sunsets?” Ben asked.

“What?” she responded.

“It’s the earth’s way of telling us, it’s okay to start over because this day has ended and you get to start a new tomorrow,” he said.

“And so whatever happened, whatever you did, whatever you said, it’s okay, because you’re going to have a new sunrise tomorrow.”

Press play to hear from Grace’s sister:

Every Memory Has Its Place

I connected with my mom when she said her memories, now, are formed by people.

If there’s any lesson I’ve learned it’s that who we surround ourselves with now, impacts how we remember ourselves and our lives in the future.

Grace’s mom on her wedding day, 1987. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

I love my current neighborhood, it’s always been somewhat of a safe haven for me.

But it also holds a lot of memories of a friendship that I’m no longer a part of. Some of my most frequented neighborhood spots, Loyola Beach, the Target on Sheridan or the Raising Canes near the red line, all hold very distinct memories.

It’s something I’ve been forced to face as I’ve built new memories in the same place where these old memories reside.

Writing this story brought a lot of those memories back with an unwelcome nostalgia.

Unlike my sister, my mom and grandma stray from dwelling on the past, but they do what they can to learn from it and that’s what I’m trying to do.

Now, Loyola Beach represents multiple things to me.

It’s a place where good memories are made and bad ones are remembered. That beach has been a refuge in the midst of some of my worst moments.

It’s a perfect storm, rife with the duality of possibility and regret.

Returning to places where you have good memories can sometimes be just as hard as returning to places where you have bad ones. That’s a feeling my mom identifies with.

“When I return to a place where I have a strong memory, I sometimes have the feeling that I should have left that place in my memory,” she said.

“Because sometimes going back, you realize that there’s a little bit of disappointment.”

At first, walking around my neighborhood brought back some of that disappointment, remembering good memories with people that are no longer in my life.

Grace’s sister (left) and Grace (right), 1999. Courtesy of Grace Del Vecchio, 14 East

But now, when this happens, I look to my sister for inspiration and I build new memories and I reclaim these places from my former self.

Because every memory has its place – this is true – but I won’t be held hostage by the memories that once occupied these places.

I’ll build new ones. I’ll move forward. And it’ll be okay because I’m going to have a new sunrise tomorrow.

Header image by Samarah Nasir

NO COMMENT