This story discusses abortion and has mentions of sexual assault.

Editor’s Note: At the time of publication on Thursday night, the U.S. Supreme Court decision regarding Dobbs v. Jackson had not yet been released. As of June 24, 2022, protections that secure the right to abortion, including Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, have been overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court in a vote of 6-3.

Sammy Lines vividly remembers the illegal abortion she had in 1969. As she sat on the table with her legs up, she watched the doctor perform her procedure. She sat looking at her doctor’s mouth from which a cigarette dangled. Transfixed by the ash that was growing longer and longer at the tip of the cigarette, all she remembers is hoping that the ash would not fall into her vagina.

Just a couple weeks later, Lines opened her local newspaper, in a town about 200 miles upstate from New York City. As she turned to page three of the paper, she saw an article she would never forget. The same doctor who had performed her illegal abortion had perforated another woman’s uterus, and she had died.

“That could have been me,” Lines says today. “I have heard awful stories, really terrible stories of things that happen to people, and I was really, really lucky, especially considering this man was an alcoholic. He could have slipped with me, too. His hand could have been shaking.”

A U.S. Supreme Court document leaked on May 2 detailed a draft decision that would overturn Roe v. Wade. The 1973 decision gives women the right to safe, legal abortion. Almost 50 years later, Roe v. Wade could be overturned by the end of June when the court releases its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case about a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

Hundreds of protesters begin to gather in Millennium Park for an abortion rights protest on May 14. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

In anticipation, people have taken to the streets to demand the U.S. Supreme Court to continue protecting the right to abortion. A few women in Chicago who lived through the years preceding Roe v. Wade came together in January to start a Chicago chapter for pro-choice group Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights.

Protesters shout in support during the Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights protest in Millennium Park on May 14. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

Some of their stories will be recounted in this article to give a glimpse of what illegal abortions and not having the choice to decide have looked like for three women. They made it clear that their stories are just one sliver of what other women have experienced. They cannot speak for all women’s experiences.

Sammy Lines listens to a speaker during an abortion rights protest on May 19 at the Chicago Federal Plaza. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

Lines sits or stands off to the side during the Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights protests in Chicago. She cheers on the crowd and listens intently when people take the microphone and voice their concerns for the future and the potential reversal of Roe v. Wade.

Lines usually watches intently in the crowd during protests, usually listening to support all the speakers. However quiet she is during the protest, when she begins to tell her story, she does not hold back.

Lines’ friends had found a doctor for her when she realized that she was pregnant, and having no other option, decided to go see him. Her boyfriend at the time drove her to the doctor’s office and the doctor took her into one of his rooms before closing time.

“I wanted something to happen to me,” Lines remembers thinking before having the abortion. “I wanted to die.”

Lines now guesses that by the time she had gone to get an abortion, she was around two to three months pregnant, but she told the doctor she was only two months. She did not want him to say no, so she lied. There are different medical procedures for abortions depending on how far along a woman is in her pregnancy, so not having medical confirmation of how far along her pregnancy was and going off of gut instinct could have been dangerous.

The doctor did not wear a mask, and she did not know whether the instruments he was using were sterile.

“I didn’t feel pain,” Lines said. “I did feel scraping, but it was not intense.”

Some details are more difficult to recount. Lines cannot remember if she was 19 or 20. She cannot remember how long the procedure lasted, but some details paint vivid pictures in her memory, like imagining her doctor’s cigarette ash growing longer and wondering if it would fall.

She cannot remember if the doctor was drunk when he performed her abortion, but she would not be surprised if told that he was. He never said a word to her that she can remember, except at the very end. He pulled a few tissues from somewhere and handed them to her.

“Here. Put these in your panties,” Lines remembers him saying to her. With that, she walked out of the room, got into her boyfriend’s car and continued on with her life.

After the procedure, she bled for over a week.

“I bled like a stuffed pig,” Lines remembers.

Lines went back to college after the procedure but would not stop bleeding. As far as she can remember, every time she would stand up, blood would gush out, and she felt sick. One of her friends’ family members was a gynecologist, so she went to get a checkup at his office. She remembers him saying that her tubes were scarred, and she may never be able to get pregnant again and could possibly die.

She cried. As she lay in the student infirmary over the next few days, she imagined dying, but soon, she was diagnosed with the flu. The gynecologist had never checked her temperature or throat.

For a while, Lines did not tell her family about her abortion for fear of their reactions. In the 1980s, she started to speak out for women’s rights and had to tell her parents about her abortion before they found their daughter on the news.

Today, Lines thinks she could have told her parents about her abortion, but then, she was afraid. After Roe v. Wade was decided, Lines’ sister had a legal abortion, and her mother escorted her. Lines does not regret her decision today.

“I didn’t want to quit school. I didn’t want to get married. I didn’t want to have a baby. I didn’t want to – I had to,” Lines says now, putting an emphasis on the word had to clarify that to her, there was no other option. “I just had to, and I’m glad that I did it. If I was in the same circumstances, I would do it again.”

Jessie Davis smiles as she watches a speaker at the Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights protest on May 19 at the Chicago Federal Plaza. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

Jessie Davis is always setting up for the protests and taking them down, and she is very vocal. She tells her story to hundreds of protesters in the hope that it will ignite their passion to fight with her. Over 50 years after having an illegal abortion and fighting to protect abortion rights, she projects her stories to as many people as she can.

“Women have the right to decide what they want to do with their bodies,” Davis said, getting lost in thoughts of remembering how long she has been fighting for women’s rights. “I’ve been fighting for that forever.”

At 19 years old, Davis found herself scared to death when she realized she was pregnant. She had no support, and abortion was illegal. One of her friends who worked in the medical field tipped her off that she could take one action if she wanted an abortion. Davis took her chance.

After talking with a social worker, she was told that she qualified to go before a board. In Santa Barbara, California, Davis approached a group of psychiatrists, social workers, doctors, and other businessmen from the community that sat on the hospital board. She said that she remembers feeling as though she were in a court case. The cross examination took hours, it seemed. They asked questions like: “How did you get pregnant? Where is the father? Why did you do this? Does your family know about it?”

“It was really degrading in a lot of ways,” Davis said. “I felt very much on the defensive and sort of trying to keep my wits about me, but it was a demeaning kind of cross examination that made me feel like I was like worse than trash, like as my father once would say, ‘A woman of ill repute’ or ‘an easy mark.’ That’s the way they kind of – my father’s generation would describe a woman who had sex outside of marriage.”

Eventually, Davis felt as though she figured out the only way they would agree to allow her to have a legal abortion. She told them she would take her own life. At that point, the court thought she was crazy enough to warrant getting an abortion.

“There was nobody who was on that board that was on my side other than the fact that they thought that, well, if we don’t give her an abortion, she’ll commit suicide, because that’s what I told them,” Davis recalls.

Davis speaks with another protester as they prepare for a rally at the Chicago Federal Plaza on May 19. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

After being shamed and taunted, Davis was told by the board that she could have an abortion. She went to the hospital soon after. She was shaved and put under anesthesia, like anyone would be for major surgery. People do not have to be put under anesthesia to have an abortion, but it is an option. Other options, like the abortion pill, do not require anesthesia.

While going in and out of consciousness under anesthesia, Davis was confronted by a nurse.

“You kill babies. We save babies,” Davis recalls the nurse saying.

“No. This is my life. I’m gonna make the decision about whether I’m going to have a child now or not, and I’m not ready,” Davis remembers replying. After that, she lost consciousness. Later that afternoon, she was out of the hospital and went home to her apartment.

She did not bleed much. She did not suffer mental or physical damage, but she does remember feeling socially unaccepted.

“At that time, if you got an abortion or got pregnant, that was social suicide,” Davis remembers. “You might as well have packed up your bag and moved to another place, another planet. You either went to a home for unwed mothers or you were socially shunned, and your parents were devastated, and their social groupings all knew that they had a daughter that got pregnant without being married.”

It was not until years later when Davis told her story. In front of Stroger Hospital in Chicago in the 1970s, which at that time had a septic ward for people who had botched abortions, Davis told her story. Some people who were her friends had no idea that she had had an abortion.

“It was an extremely difficult and very traumatic experience to go through,” Davis says now, looking back. “I felt very confident in my choice, but it was a hard dialogue with a lot of people who at that time did not agree with the fact that women had the right to choose.”

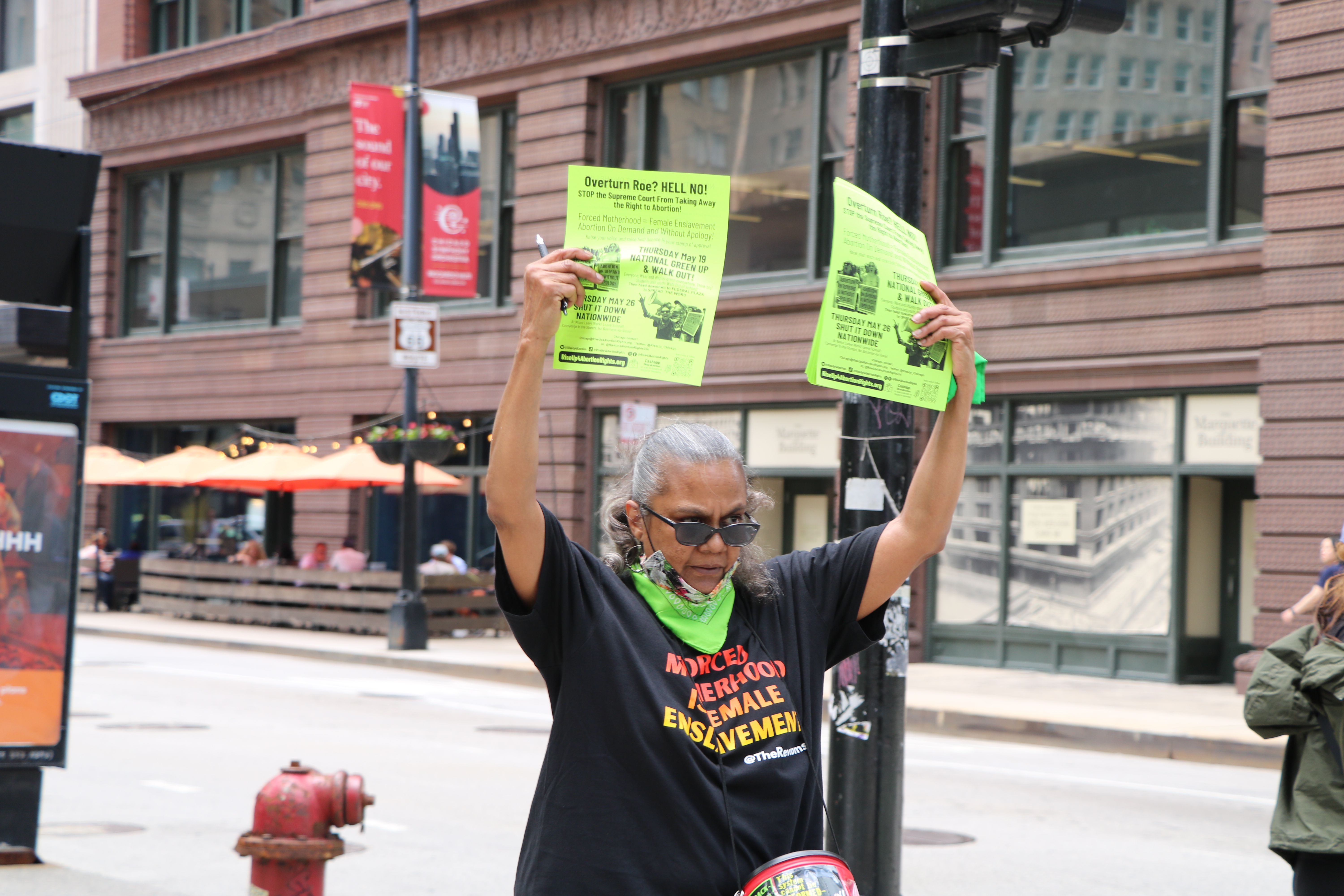

Gia Estavia walks down Adams Street with flyers during an abortion rights protest on May 19. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

Gia Estavia did not have a choice when she was 14 years old. The choice was made for her by her mother and doctor and all she could do was sit and listen to them decide what was best for her body, future and happiness. They decided that she would keep the baby.

At 14 years old, Estavia was raped. While she had the baby in Chicago in 1976 after Roe v. Wade was decided, she was not given a choice.

“Had I had a choice, I would not have given birth to a child at that age,” Estavia said. “My life would have been different. But, I did, and my life is what it is today, and for that, I am out here doing what I can so that all women have choices over their bodies.”

At the protests, Estavia passes out flyers to anybody walking in the streets. She tries to talk to as many people as possible and asks them to join the fight. As soon as she walks into the protest, she wastes no time in finding the flyers and going to the streets. She continues to fight for the right to choose.

When Estavia tells her story, her words are concise. It hurts her to still think about what she went through and the agony of not being given the chance to speak her pain. She wants to tell her story to prompt others to join the fight with her, but it still hurts to think about the memories. Now, it is painful for her to think that the U.S. Supreme Court may be taking away the right to abortion.

“Roe v. Wade is in place for a reason,” Estavia said. “Women will die if they overturn this.”

Estavia shares flyers with another protester during a protest on May 19 at the Chicago Federal Plaza. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

Her daughter is now in her 40s, but after getting pregnant, Estavia was scared. She could not provide financially for her child, and she had no idea how to be a mother as a teenager. She found it even more difficult because the emotional and physical scars of the rape haunted her. This is the trauma she faced while raising her daughter, who felt like a reminder of the trauma.

“The horrific part of the rape: having to relive it through seeing my child, through scars that I have from the rape because he left me to die,” Estavia said. “I have a one-inch scar on my head as a result of that that I see every day. It’s hard, but I use that as my strength to motivate and tell others about what is going on in the world so that we can make changes to better choices for women.”

She is out here on this day so that others will not have to experience the pain of not being able to choose.

Davis lies on the ground in the intersection of State Street and Jackson Boulevard during a die-in protest on June 6. They are capturing what could happen to people if abortion becomes illegal: people could die. Photo by Cary Robbins, 14 East

Today, Davis and Lines each have a child, and they are happy that they were able to wait until they were older and more financially stable. According to the CDC, six in 10 women who have had an abortion are already mothers.

“I was really scared, and I was torn because I wasn’t in the position to bring a child in the world,” Jessie says, remembering how she felt when she realized she was pregnant. “I [had a child] at a much later date, but at that point, I was just totally unprepared.”

Davis, humiliated in front of members of her community, was allowed a legal procedure, and she does not remember experiencing pain either physically or emotionally. Lines faced both physical and emotional damage after her illegal abortion that left her scared and ashamed to tell her family. Estavia was not given a choice, and that altered her entire life at the age of 15.

Their stories vary greatly, but they each tell a part of the same story: what it could look like again for women in the U.S. if the right to abortion is taken away. For fifty years and almost their whole lives, all three women have been fighting for the same cause: the right to make their own decisions for their bodies.

“Abortion on demand and without apology,” Davis said, and with that, she went back into the crowd to continue the fight.

Sexual Violence

If you’ve experienced sexual violence you can call the RAINN hotline at 1-800-656-4673 for help.

If you are a DePaul student, the university’s Office of Health Promotion and Wellness has a variety of resources. You can also contact DePaul’s Survivor Support Advocates, who are confidential resources in that office, at hpw@depaul.edu or (773)325-7129.

Reproductive Health

Schedule an appointment at the nearest a Planned Parenthood near you by visiting their website or calling 1-800-230-PLAN.

Chicago Abortion Fund provides a list of Chicago and Illinois resources ranging from childcare to birth control and health assistance. Their helpline is open Monday, Wednesday, Friday between 6 a.m. and 2 p.m. CT. Call 312-663-0338.

Header illustration by Annie Gidionsen

NO COMMENT