“For the entirety of the pandemic, that one word lurked in the back of my head, a label that I fit under but could not understand: ‘immunocompromised.’”

“Immunocompromised.” A word that three years ago was not in my vocabulary became one of the scariest words in the English language for me overnight. In early 2020, it popped up in nearly every article as COVID-19 spread across the world and reached the United States. I sat there, packing up my dorm room after being told to move out as a result of the pandemic, as the news filled my inbox with warnings for immunocompromised people – articles spoke of how at risk we were and how COVID-19 could be extra life-threatening.

Overall, the word immunocompromised was an extremely confusing and anxiety-inducing word for many people; I was scared because I had been living with a chronic disease my whole life and was in a steady state of remission. I could not gauge how at-risk I was. For the entirety of the pandemic, that one word lurked in the back of my head. A label that I fit under but could not understand: “immunocompromised.”

I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at 18 months old. I spent years traveling to different hospitals and going to doctors across the country, many of whom could not offer me any help. I do not have a lot of memories from these times, but there are a couple of foggy images here and there: watching Winnie the Pooh late at night in a hospital bed with my dad worrying that the nurses would say it was too late to watch TV, watching fireworks through the hospital window with some “Get Well Soon” balloons in the corner and waking up from surgery with hallucinations from the medications I was given and seeing my mom with two heads and my dad with three eyes. Pretty unpleasant memories all around.

Riley’s parents care for him while he is in the hospital as a toddler. Photo courtesy of Erin and Ryan Andrews.

According to The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Crohn’s disease is one type of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, or IBD (not to be confused with Irritable Bowel Syndrome, or IBS). “Under normal circumstances, harmless bacteria that’s present in the GI tract are protected from an immune system attack…In people with IBD, these harmless bacteria are mistaken for foreign invaders and the immune system mounts a response,” says the website for the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. “The inflammation caused by the immune response does not go away. This leads to chronic inflammation, ulceration, thickening of the intestinal wall, and, eventually, symptoms of Crohn’s disease.”

Eventually, I would enter remission and my disease would calm down. I am still in remission, and feel relatively healthy most of the time, but it is not without struggles. After 20 years, I still go in for medication infusions every six weeks and sit with an IV for hours at a time. If I get sick with anything, even the common cold, my gut gets hit hard.

Riley makes fun memories with his parents despite having to eat through a feeding tube at a young age. Photo courtesy of Erin and Ryan Andrews

Because of that, hearing about a new virus was scary enough without the label of “immunocompromised” hanging over my head. I called my doctors with questions consistently, and often could not make sense of what I was being told. I talked to my parents who had been helping me with my disease my whole life, and I still could not figure out what my situation was.

This was new for me. The times when doctors could not explain what was wrong with me was supposed to be in the past, back when I was an infant. I had the gift of answers for as long as I could remember, and I know that I am lucky for that, but I was also used to it. The problem was that the coronavirus outbreak was one-of-a-kind – no one had any answers to give me.

This constant state of confusion did a number on my sense of identity and mental health. It took until I was in high school to truly start to believe that having a chronic illness did not have to be something that affected my perception of myself. Just because I had to keep a closer eye on my health and body than other people my age didn’t usually mean that I had to worry about how other people would perceive it.

My disease was mine, and mine alone. I had complete control of how I thought about it, and a lot of control over how I handled it. For a long time, I lived in the mindset that I was perfectly healthy and was no different than anybody else. The term “immunocompromised” took all of that away from me and I felt like I reverted back to my identity as a sick child.

Riley receives infusions as part of his Crohn’s treatment at the same hospital in 2005 and 2015. Photo courtesy of Erin Andrews

Suddenly, I was one of the top concerns of my whole family. They would try their best to put me at ease: “You’re going to be fine … You probably aren’t especially at risk … Try not to worry too much.” I tried my best to believe my parents, but there were signs that told me I might not be fine. Everyone in my family went on high alert and greatly reduced their number of interactions with people outside of our family because of my disease. I could see my girlfriend, provided that it was only on outdoor walks and we remained six feet apart the entire time.

This felt fair to me, until I noticed that my sister was going to a friend’s house. I knew that she would have to remain outside, but it still was better than the walks I was having with my girlfriend – the sidewalk of my neighborhood is only so private and romantic. Dogs barked all the time and standing six feet apart put a damper on the mood. My parents and I worked out a system where my girlfriend could spend time at our house so that I was not exposed to her family, but this was the first indication that I was definitely considered immunocompromised. I was also kept from moving back to the city for a long time, until more things could be figured out about the vaccine and precautions.

Riley and his girlfriend celebrate their second anniversary with a socially distant picnic in April 2020. After the photo, they had to return to opposite ends of the blanket. Photo courtesy of Susan Thomas

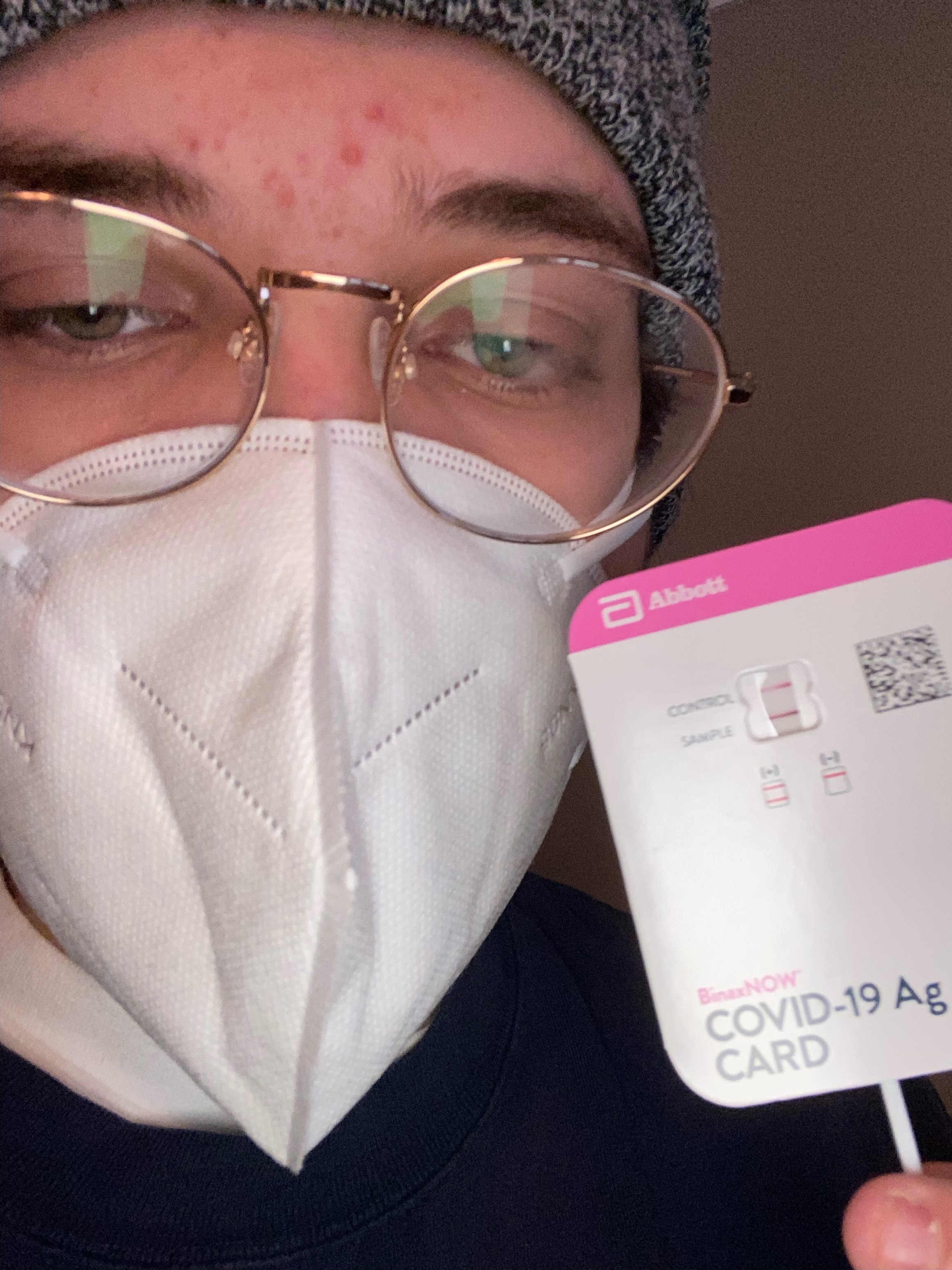

The most confusing part of being immunocompromised came when I actually contracted COVID-19. After fully avoiding it for almost two whole years, I caught COVID-19 at a Christmas dinner in 2021. I took a rapid test and the dreaded second line appeared – whatever little color I had in my face drained. This was the moment I had feared the most. My thoughts were flooded with what ifs: “What if I’m hospitalized?” “What if my taste and smell never come back?” “What if I get more of my family sick?”

I never lost my taste and smell, and I did not have to spend a night in a hospital room. However, I was asleep more than I was awake and when I was awake, I was miserable. Despite all of the times I heard “You will be okay” and “It isn’t going to be dangerous for you” from family and medical professionals alike, I was still informed by my doctors that I was priority one for an antibody infusion, something I had never heard of before but knew was serious. Nothing makes you feel like a sick little kid again than being top priority for an experimental treatment. When I went into the infusion room and saw the doctors covered from head-to-toe, I felt dangerous. I was in a room with four other people and I was petrified of everyone, including myself.

Riley takes a selfie after receiving a positive COVID test result at home on December 29, 2021. He took the photo to document his results as he tried to process the news. Photo by Riley Andrews, 14 East

I recovered from the coronavirus after 10 days, with little lingering side effects. I entered into a short period of time where it was extremely unlikely to contract COVID-19 again. This was also confusing, as I was unsure what to do with my “immunocompromised” label. I tried to relax and make sense of myself again.

I came to the conclusion that yes, I am immunocompromised, but that doesn’t have to be the only label I put on myself. I went through the same journey that I went through with accepting my disease in general. Being immunocompromised is a sad truth that applies to me. However, that does not mean it has to be the only thing that I am. I do not have to revert back to being a sick child. I have control over my thoughts and my identity, and I will not let the pandemic take that away from me as it has already taken so many other things.

In the end, I still do not have any answers, only the experience of having the virus as an immunocompromised person. I was lucky to be someone who turned out okay. I do not hold anyone responsible for my confusion because everyone was confused. I also know that this is not only my story. So many people out there went through similar experiences. You are not alone, and you are invited to share your thoughts in a safe space.

Header illustration by Annie Gidionsen

NO COMMENT