For Semillas Raíces, this is what restorative justice means.

On a warm sunny Saturday afternoon in April, the Semillas y Raíces garden in North Lawndale held space for its monthly ceremony.

Walking up to the fenced garden through the alleyway entrance I am first greeted by a blue sign that reads “Native American Church” and to the right of that is a welcome sign detailing what the space is about. My eyes are immediately drawn to the colorful murals adorning the fence on either end of the ample garden as I walk in. The murals depict human connection to the earth which is an accurate representation of what happens in the space. Semillas y Raíces stands for seeds and roots.

Semillas y Raíces, which is located in the North Lawndale neighborhood, is a space for individuals and organizations to build community and learn restorative justice practices Photo by Citlali Perez, 14 East

A brick fire pit is located in the middle of the garden where Richard Lawson, the fire keeper, prepares the sacred fire, which people are advised not to take pictures of.

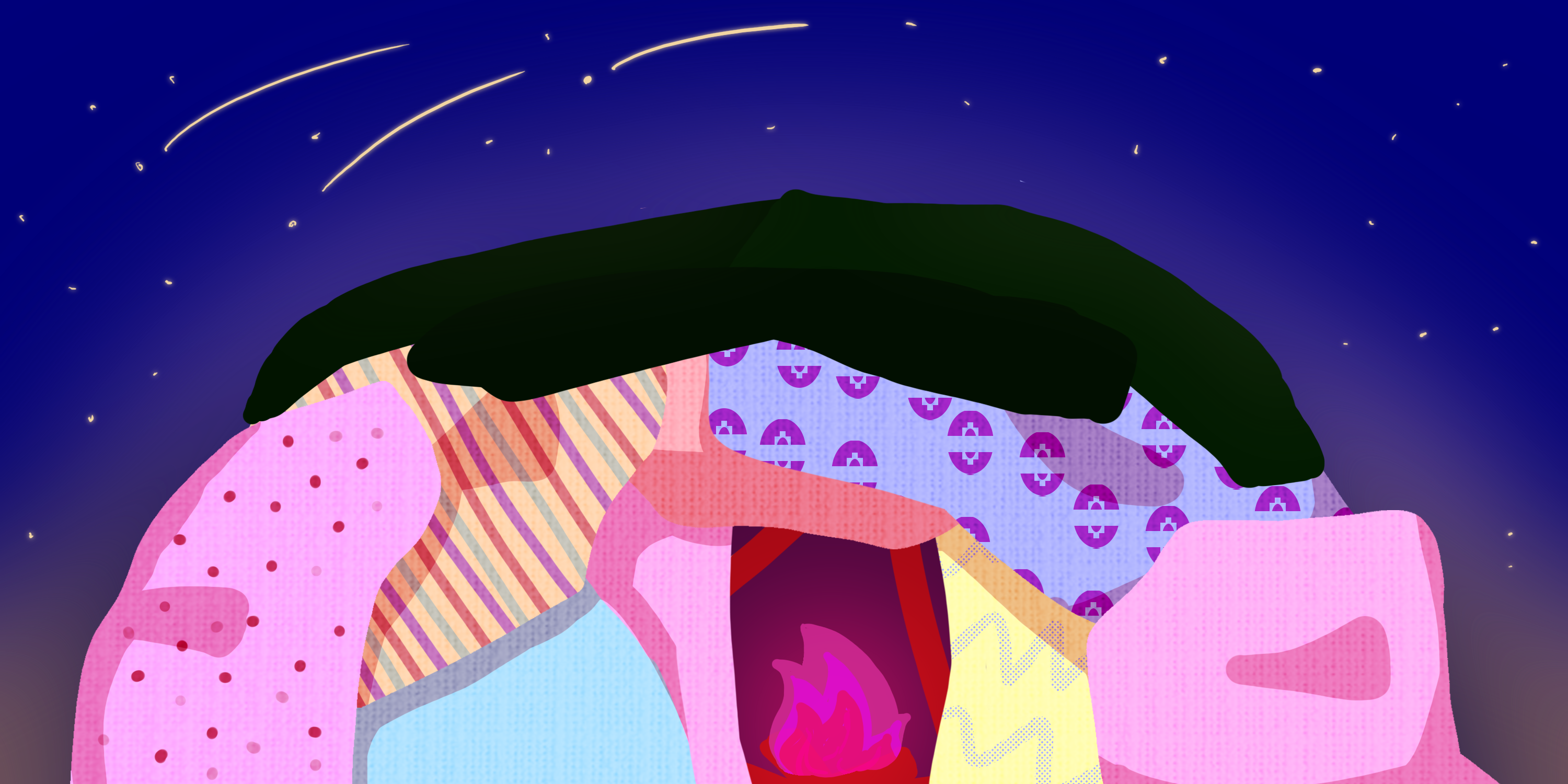

Right next to the firepit is the wooden lodge made of thick oak branches forming a dome and held tightly together by rope. The ceremony participants helped set up the lodge by covering it with a layer of blankets followed by heavy and dark-colored tarps to keep the light and air out.

This sweat lodge ceremony has been practiced by indigenous communities of varying geographies. In Mexico and Central America, it is known as temazcal.

The majority of the participants in attendance that day have been introduced to Semillas y Raíces by the director of the space, Tomas Ramirez. Ramirez is also a Peace, Justice and Conflict Studies professor at DePaul University. A couple of the participants have met Ramirez through a Peace, Justice and Conflict Studies course they took at DePaul.

This included Megan Mia Galarza, who was attending the sweat lodge ceremony for the second time.

Megan Mia Galarza pulls a tarp over the sweat lodge at Semillas y Raíces garden in North Lawndale. Photo By Citlali Perez, 14 East

“It was just very ironic timing, meeting Tomas, because I didn’t realize that we were already in a community with each other because we had so many mutual people and mutual friends,” she said.

It is difficult to trace the various spaces that Ramirez is connected to as a practitioner of restorative justice. Semillas y Raíces holds space for individuals and organizations seeking to build community and learn restorative justice practices. The space is open to anyone and everyone, which is telling of Ramirez’s vast network.

The term restorative justice was brought about and popularized through academic settings. Ramirez, who is of Indigenous descent, defines it simply as “striving to be in right relationship.” The key elements of this are community building, community healing, and community accountability.

“Restorative justice, restorative practices are the protocols, the processes that do not see crime as a violation of laws, but as a violation of relationships. And those relationships have rights and obligations, and the central obligation is to make things right,” says Ramirez.

As for who gets to be a practitioner of restorative justice, Ramirez says a lot of development, mentorship and humility are required. He doesn’t take his title as practitioner lightly and, in fact, warns about upholding hierarchy through emphasizing titles such as healer.

Ramirez says, “We have to really work on our stuff. It’s not about hierarchy. We hear a lot of people that do work and they say, ‘I’m a community healer, I am a circle keeper, I am whatever’– that’s savior mentality and that’s hierarchy, which is the opposite of a collective process for healing, community building, and accountability.” The harm in this he explains is, “that instead of having an oppressive force who might be light skin, is an oppressive force that looks just like us with a lot more woke vocabulary and more politically correct. ”

Ramirez grew up with these practices and learned from his elders and mentors.

“So all of the stuff that I originally knew about restorative practices were not called restorative practice or restorative justice, they’re simply called tradition,” said Ramirez.

Other terms such as transformative or healing justice have also surfaced in the mainstream, although Ramirez explains these all go back to being in right relationship.

Restorative justice offers an alternative to addressing conflict among people by addressing the root cause. This requires a reframing of perpetrator and offender, to people who cause harm and people who receive harm, with the understanding that people who cause harm have experienced it as well.

“So one of the main purposes of restorative practices, restorative healing or transformational practices is to include people, to be in community,” said Ramirez.

Ramirez outlines the three settings in which restorative justice work takes place: institutions which include schools, prisons, and courts; third spaces, which include community organizing groups, drop-in centers, and other collectives with a specific purpose; and lastly, direct street outreach.

“In all three settings, really beautiful work takes place, but also it has very specific challenges,” said Ramirez. He has done restorative justice work in all three settings and the work of Semillas y Raíces also reaches these spaces.

Ramirez facilitates restorative justice circles at the Restorative Justice Community Court in North Lawndale, which offers youth who would otherwise be subject to incarceration an alternative option. He says, “The institutions that we have within the criminal legal model are not designed for the well being of marginalized communities, especially Black and Brown communities. So we should not lie to ourselves. But yet within that setting, cultural transformation is always possible.”

Ramirez emphasized that it is important to work in the community you live in. North Lawndale has been particularly impacted by excessive juvenile arrests. Ramirez says, “I live in the community where I work. So by me working within this institution, I’m also trying to create spaces that elevate the quality of life of my neighbors or the people of my community. And when I do that, my quality of life improves.”

Samantha Arechiga is a student at DePaul and has been deeply involved with the organization since 2019. She was in attendance at the ceremony that Saturday.

Megan Mia Galarza and another attendee work together to fold a tarp that was used during the ceremony. Photo By Citlali Perez, 14 East

“Thanks to Semillas and my work there, I’ve been able to land a job doing RJ [restorative justice] in CPS and have discovered that working with RJ and community building and using culture through that, is something I want to spend my life doing. Semillas has truly changed my life in a meaningful way,” Arechiga said.

Moises Moreno, an organizer with Pilsen Alliance, a social justice organization, was also present at the ceremony. He explains that Pilsen Alliance got involved in 2019 and is seeking to rebuild the community and culture within the organization.

He explains that although not all of the organization’s members have been interested in continuing to be involved with Semillas y Raííces, his participation has helped him connect with himself.

Ramirez has worked with a lot of marginalized communities and noticed that restorative justice had been received well. The reason being, he explains, “a lot of the traditional protocols for the development of human beings give you your worth, giving you your value out of being able to support others, out of being able to deal with others, and out of being able to contribute to others.” This is in contrast to a society that makes it difficult for a lot of people to succeed.

Semillas y Raíces maintains the Indigenous roots of restorative justice practice by being in community with the earth and keeping the space open to everyone. Along with temazcal ceremonies, there are also garden work days and other engagement opportunities you can find out about in their Instagram account.

Header illustration by Samarah Nasir

NO COMMENT