“Our perception of art – and of the world – is generally limited to the Western hemisphere. For many, this was one of the first exhibitions they attended that showcased non-Western abstract art.”

Northwestern’s Block Museum opened an exhibition that explores abstraction in the Arab world. Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s incorporates artworks that reflect the diversity of countries, cultures and artists in the Arab world. It also examines the ways Arab abstraction relates to the international art scene.

Taking Shape began at NYU, where it was curated by Lynn Gumpert, the acting director of the Grey Art Gallery, and Suheyla Takesh, curator at the Barjeel Art Foundation. The exhibition circulated through several universities before making its way to Northwestern on September 22, where it remains free to the public through December 4.

Arab history is highly complex because it describes a broad geographical region extending across several countries. During the 20th century, Arab nationalism surged and militant efforts challenged Western occupation. Decolonization of the Arab world allowed artists to travel, often to Europe and the United States, where they picked up several Western modernisms. Arab abstraction emerged from the application of these observed techniques in the context of their own geopolitical and cultural experience.

“The modernism Arab artists produce share some of the same tenets of Western modernism—value on individual experience, formal experimentation, contemporary subjects—but it has its own unique qualities for having been made in Arabic countries and by artists that have lived that particular geopolitical and social experience,” said Mark Pohlad, an art history professor at DePaul University.

A group of visitors listen to a guide talk about the exhibit, Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s which is showing at Northwestern University’s Block Museum until December 4. Photo by Sam Freeman, 14 East

Western influence is distinguishable in the artwork. Untitled by Hussein Madi draws inspiration from European artists, such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as well as Islamic art. Those European influences are clearly present in this piece that illustrates abstract shapes, harsh lines and bold colors.

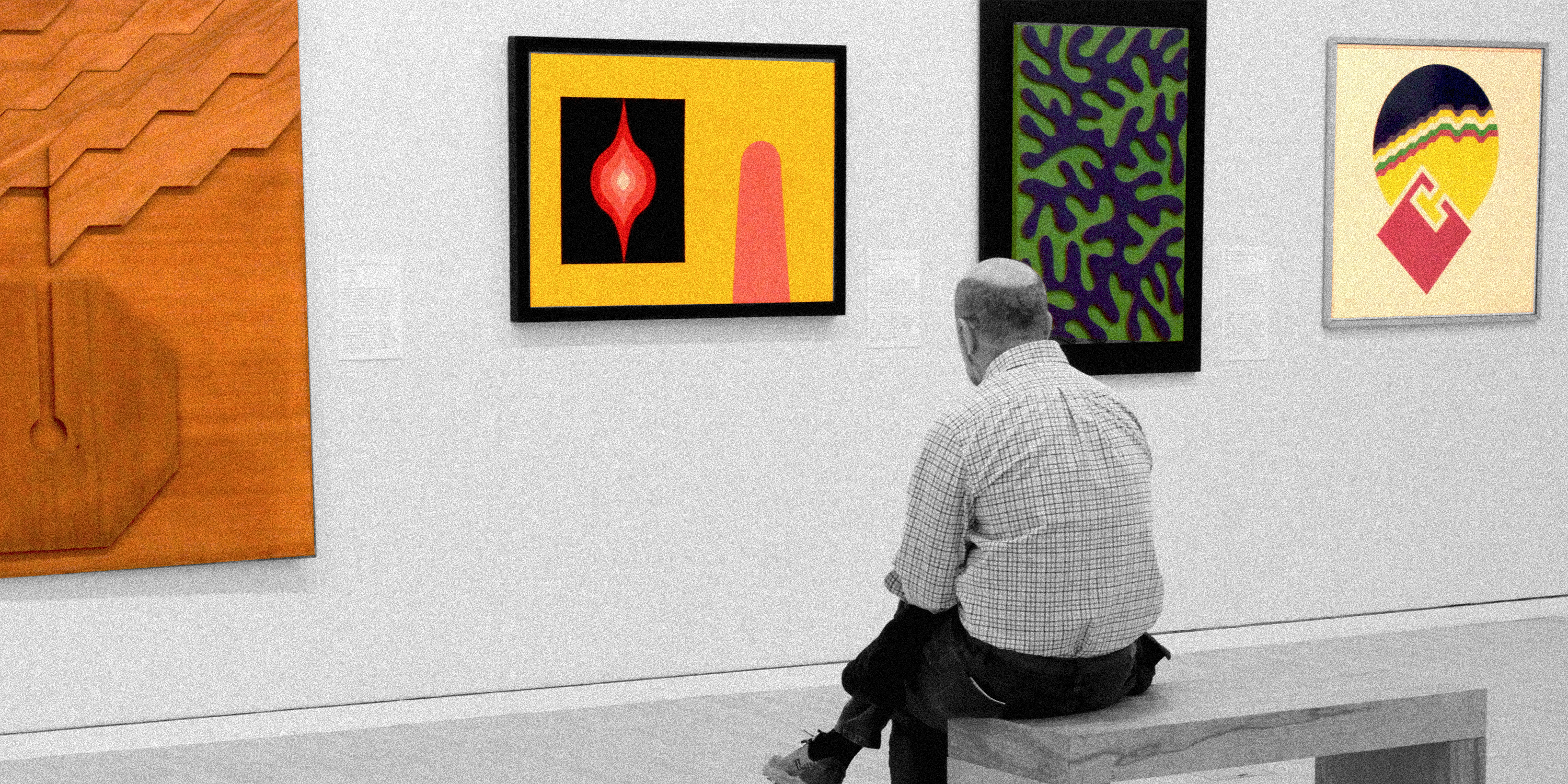

Abstraction is characterized as breaking through artistic boundaries and ambiguity, and the curatorial choices support this theme. In the exhibition, there is a great use of open space to draw the viewer’s attention to the art. The openness allows the art to take up the space with its vibrant colors and expressive forms.

“I was kind of thinking when I first came here, I was comparing the space to how they used it in an exhibition last year,” said Jaharia Knowles, a student associate of the Block Museum. “The last exhibition was a little bit smaller, and there were a bunch of different walls covering things.”

Each piece is accompanied by a thorough yet concise summary of the artist and history. The summaries help the viewer understand the different geopolitical and social backgrounds of a work. None of the pieces were covered by glass, which enhanced the texture and overall experience of abstract art.

“I guess it’s like a little bit more open, which makes sense with the theme of abstract art. Like to have an open space, you know, to not be bound by too many walls,” said Knowles.

The art itself is striking, and people were captured by its remarkable boldness. Knowles’ favorite piece in the exhibition, Al-Tamazzuq (Torn) by Hamed Abdalla, depicts a brightly painted center with a blue-cracked background, revealing a layer beneath it.

“There’s such a huge range of styles being employed. Over there is very strict line form and then over here you have more of an exploration of color, which I think is really cool. I just love that,” said Knowles.

Sean Evans, another observer at the exhibition, offered his own perspective on one of the pieces called Alphabet by Hussein Madi, which depicts a series of 30 black graphics.

“I think it’s interesting having, you know, the Islamic prohibition on figural representation, combined with the abstract kind of graphic design of the era. They work together,” said Evans.

A museum guest walks past the art on display at Northwestern’s Block Museum. Photo by Sam Freeman, 14 East

For many, this was one of the first exhibitions they attended that showcased non-Western abstract art.

“Abstract arts have always interested me, but I’ve also only seen mostly American abstract art and European art. And I feel like that extra added element of Middle Eastern culture and Middle Eastern history is really, really cool to see,” said Knowles.

Our lack of knowledge about Arab abstraction comes from art historical canons. When we think about abstraction, we often refer to Western European artists, such as Vassily Kandinsky, Ernst Kirchner and Henri Matisse. Our perception of art – and of the world – is generally limited to the Western hemisphere.

“We in the Western world are blinded by our own canon (accepted highlights of art). We tend to measure everything by that with which we are familiar. We may discover—we will discover—that there are artists and artworks that deserve a place in what we teach, admire, and buy (in other words in our canon),” said Pohlad. “As we discover artists, we should look for the same diversity—especially women artists’ works—that we now aspire to in Western canon.”

When efforts are taken to diversify the art that we’re consuming, people learn more and their knowledge expands beyond the narrow scope of Western art. Exhibitions like Taking Shape challenge traditional art historical canons, and introduce an important perspective to the art world.

Header illustration by Magda Wilhelm

NO COMMENT