The defacement of the Abraham Lincoln stature in Chicago is a recent example of activists damaging art to call attention to a problem.

What Occurred

Behind the Chicago History Museum, a statue of Abraham Lincoln was vandalized on Indigenous Peoples Day on October 10 by an anonymous group to draw attention to the negative history of the 16th president of the United States.

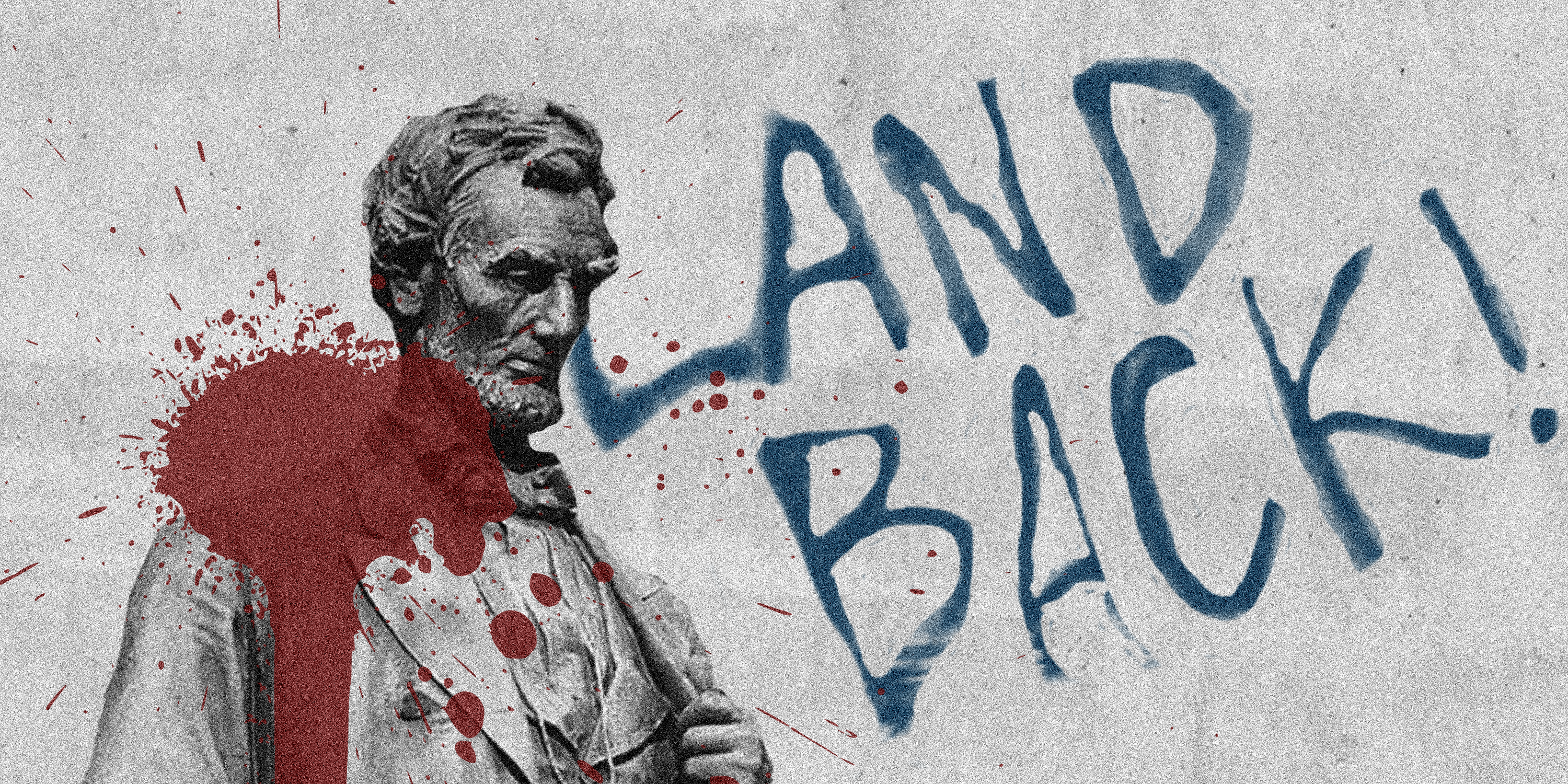

The statue was smeared with red paint on the coat jacket and hands, and the statements “Dethrone the Colonizers,” “Land Back” and “Avenge the Dakota 38” were spray painted in blue at the base.

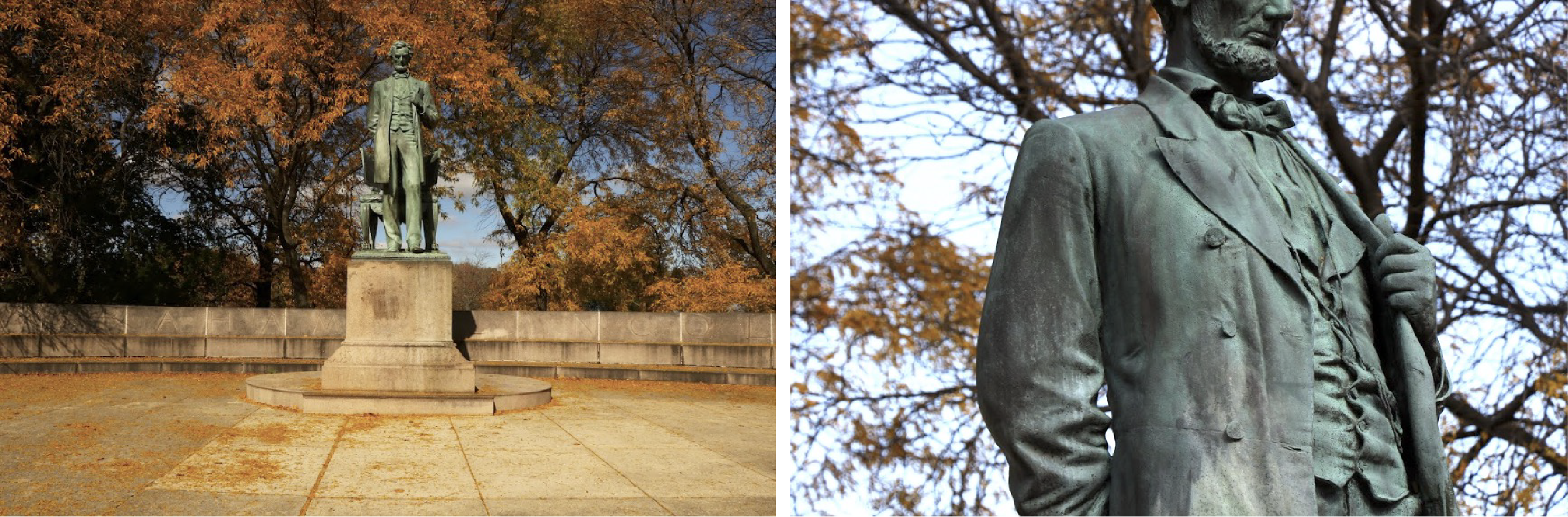

The Statue of Abraham Lincoln stands in Lincoln Park since being vandalized on October 10, by an anonymous group. It was cleaned shortly after the incident. Photo by Hailey Bosek, 14 East

The messages referenced a massacre of 38 Dakota men in 1862 after the U.S.-Dakota war. Lincoln was asked to review the conviction of 303 men, and signed off on the execution of 38.

The Dakota 38 was the largest mass execution in United States history, and the anonymous group said it wanted to draw attention to this incident as a part of its anti-colonialism efforts.

According to Block Club Chicago, the group also wrote that they seeked to “tear down the myth of Lincoln as great liberator and expose his complicity in the genocide of Indigenous peoples and theft of their lands.”

Within the week, the paint was cleaned from the site. Some hues of red paint on Lincoln’s shoulders remain as well as discoloration where the messages were painted at the base.

Recent Events

The defacement of statues has been a common form of activism. Statues that are seen to promote colonialism, racism and imperialism have been removed or toppled around the world. In 2004, a group of protestors toppled a Christopher Columbus statue on the Day of Indigenous Resistance in Venezuela. In 2015, a statue of the colonialist businessman Cecil John Rhodes was removed after frequent protests in Cape Town, South Africa. These demonstrations have also gotten violent. One person died when white nationalists and counter protestors clashed at the infamous Charleston “Unite the Right” protest.

As of late the destruction of art and paintings has started to become a more popular form of protest, as climate change activists have targeted museums and famous paintings to draw attention to the climate crisis. Two protestors from the activist group “Just Stop Oil” threw two cans of Heinz Tomato Soup on the famous Sunflowers painting by Van Gogh in London.

“We are using these actions to get media attention because we need to get people talking about this now,” said the Just Stop Oil protestor Phoebe Plummer in a TikTok video. This sentiment is shared by the president of the American Indian Association of Illinois, Dr. Doreen Weise.

“Activism draws media, and as someone once told me, any media is good media, because we’re invisible,” said Weise. “We want to be visible.”

Weise explained that the controversy surrounding the defacement or the removal of statues is a way to call attention to the often erased history of Native Americans.

“It gives the people a chance to tell their story, because unless there’s some controversy, the media doesn’t care about your story,” said Weise.

She felt that people don’t know about Dakota 38, and the continued oppression has occurred because we are not taught about the bloody history behind the oppression of Native Americans. She calls this erasure “continued genocide.”

Activism and art

With the vandalization of the Lincoln statue and several other artworks, it raises the questions: is art activism effective?

The graffiti on the Lincoln statue was intended to draw attention to the Dakota 38 massacre in United States history and critique the president who signed off on it.

Slight remnants of stains remain on the statue. Photos by Hailey Bosek, 14 East

“Maybe the point is not to convert anybody, or to wake up anybody. It’s to get the microphone, basically, and that I have a big sympathy for,” said Mark Pohlad, an art history professor at DePaul University and a Lincoln expert.

According to David Maruzzella, collection and exhibition manager at the DePaul Art Museum, some forms of art activism are more effective than others.

“The question, to my mind, isn’t, ‘Should we or should we not vandalize art?’’ but rather something like, ‘Why do we appear to value art more than the planet?’ This is why I found the Van Gogh action interesting: the work wasn’t harmed (since it was protected), but it nonetheless provoked such a dramatic response,” said Maruzzella.

Maruzzella continued, “In other words, the action staged precisely the problem of value and justification. Why does it appear that we value a painting more than the planet? What justifications or reasons do we have? I suspect whatever the reasons are, they might not be very good!”

The soup itself resembles the cost of living crisis due to the unaffordability of fuel. Many families cannot afford to heat a can of soup, said Plummer in her speech during the incident.

The vandalization of the Lincoln statue, on the other hand, is less closely tied to the work of art itself. While the red paint on the Lincoln statue symbolizes blood, the graffiti could have been done anywhere, and the overall message is slightly less effective, according to the art community.

“By pretending to ‘harm’ the painting and provoking a dramatic response, the protestors were able to draw a parallel between harming art and harming the planet (one of which they clearly think is more serious!). To put this differently, I think the Lincoln statue event didn’t address the statue part of things, but just that it shows Lincoln,” said Maruzzella.

The Van Gogh piece was not harmed during the protest. The Lincoln statue remains discolored after the vandalization. But that’s a sacrifice many are willing to make to bring attention to an issue.

“From an activist standpoint, you have to do so much just to capture people’s attention, there’s just so much news, so much media, such an online kind of noise universe, that it might not be such a horrible idea,” said Pohlad. “If your point is to attract attention. And in our age, just getting the attention of people is really difficult. So I understand that.”

Going Further

Weise said that she finds it hard to care about what the art community feels in regards to destruction.

“I guess I can’t be that sympathetic to it because, really, native art has never been celebrated,” said Weise. “We’re still relegated to something that is termed primitive, and so no one really cares about or values the work that our artists do.”

She believes that in order to move forward the history of Native Americans have to be recognized, along with their art.

The Lincoln statue stands behind the Chicago History Museum. Photo by Hailey Bosek, 14 East

Where these statues are

The Chicago Monuments Project is an organization that works to address unacknowledged history related to Chicago’s monuments and provide a way to appropriately recognize Chicago’s racial history. The advisory committee created a report that includes a list of statues under review for potential removal. The listed sites can be viewed via this map.

“Critique is easy in the 21st century—a quick Google search of any president, political leader, or public figure will turn up a laundry list of horrible things they either did directly, influenced or turned a blind eye to,” Maruzzella wrote in an email. “The question thus becomes: who or what do we want to memorialize (if anything!)? What values or events do we want to celebrate and which do we want to condemn? And how are we to reckon with our past?”

Header illustration by Magda Wilhelm

NO COMMENT