As DePaul University celebrates its 125th anniversary and history, Vincentian values are at the forefront. Can it reconcile these values with a legacy of white supremacy?

Content warning: This piece includes photos of blackface minstrelsy and descriptions of racist actions and performances, as well as derogatory language in primary source documents.

When DePaul University first welcomed students 125 years ago as St. Vincent’s College in 1898, it laid out a fundamental mission: educate the Catholic men of Chicago in the Vincentian tradition, using the guide of St. Vincent de Paul’s teachings and faculty who were priests trained through the Congregation of the Mission, the formal name of the Vincentian religious order.

But when it was incorporated formally as a university in December 1907, it became broadly inclusive compared to many other Catholic universities at the time.

“No test or particular religious profession shall ever be held as a requisite for admission to said University,” a paragraph in the articles of incorporation read.

In its first fifty years as a university, DePaul provided an education not just for the Catholic men of Chicago, but also for women and Jewish students, refusing to set admissions quotas for these groups at a time when such policies were commonplace. The institution also admitted veterans, non-Catholics and a small contingent of international students, pushing inclusivity as both a business strategy and a core value.

However, one group was not welcome for decades: Black students. Through restrictive admissions practices and hostile school-sponsored activities like blackface minstrel shows, DePaul’s leaders created an environment that was not as welcoming as its origin myth.

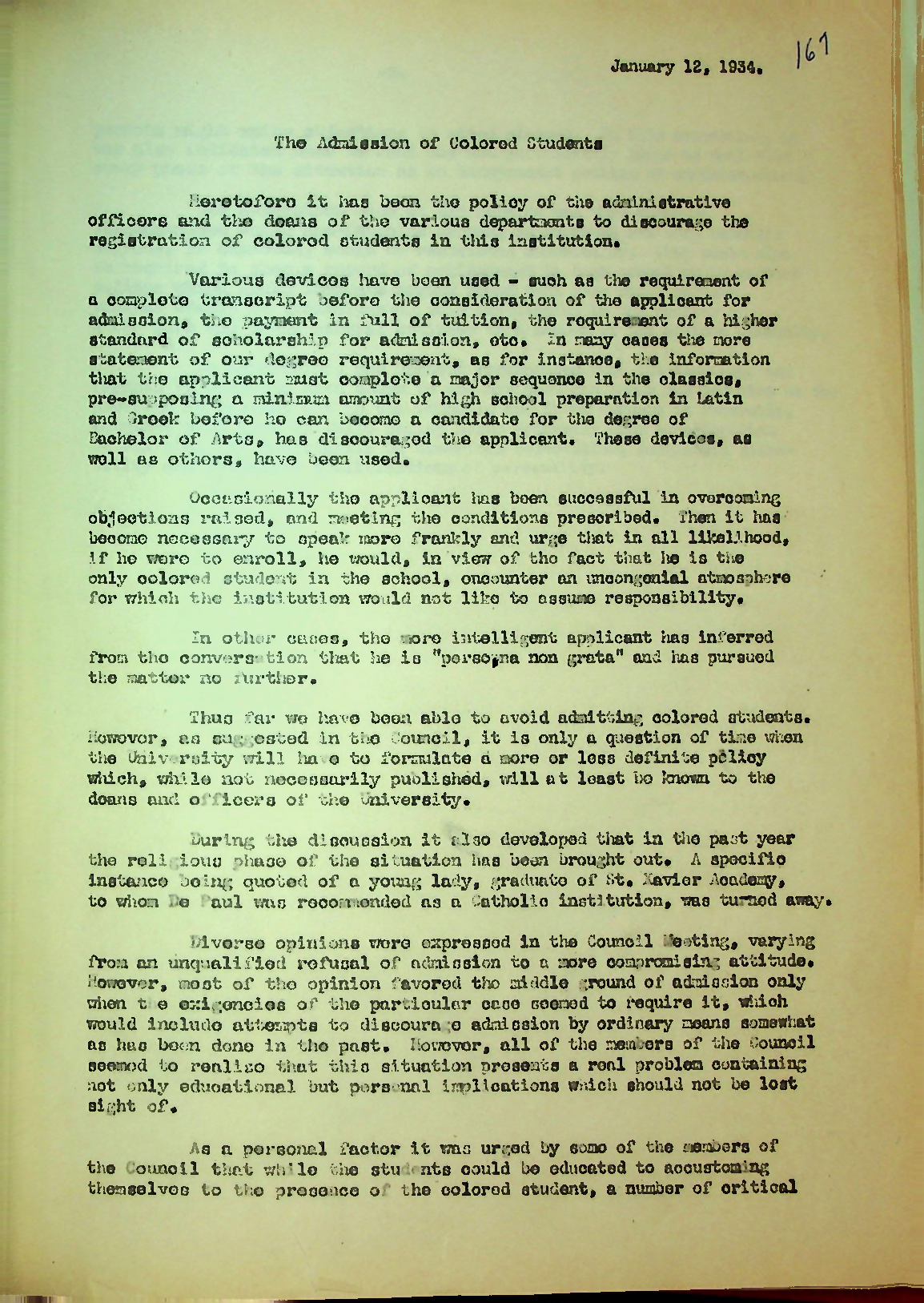

A memo from the January 1934 meeting of DePaul’s University Council detailed the ways in which administrators discouraged Black students from enrolling. The group included five members of the Congregation of the Mission, along with deans, department heads and other leaders at the university. (DePaul Special Collections and Archives) [Click to enlarge.]

In early 1934, during the height of the Great Migration, a university committee made up of DePaul leaders recorded the methods used to prevent Black students from enrolling in the university.

In a one-and-a-quarter-page memo, the committee described racist practices that had been an open secret, acknowledging that it had been, in the words of the memo, “the policy of the administrative officers and the deans … to discourage the registration of colored students in this institution.”

Barriers for prospective Black students that the committee described included requiring students to pay tuition in full at the start of the term, as well as requiring “a higher standard of scholarship” for applicants, with a comprehensive “sequence in the classics,” including studies in Latin and Greek.

If applicants met those standards, university officials would reportedly have a conversation with the student about the potentially “uncongenial atmosphere” they would face due to being at a school with an almost exclusively white student body, according to the memo, “for which the university would not like to assume responsibility.”

These methods proved effective. “Thus far, we have been able to avoid admitting colored students,” they wrote.

Some members of the council, the memo noted, argued that while white students “could be educated to accustoming themselves” to Black classmates, the university’s hesitation to admit Black students lay within the potential reaction from white parents, who “might raise objections to mixed classes.”

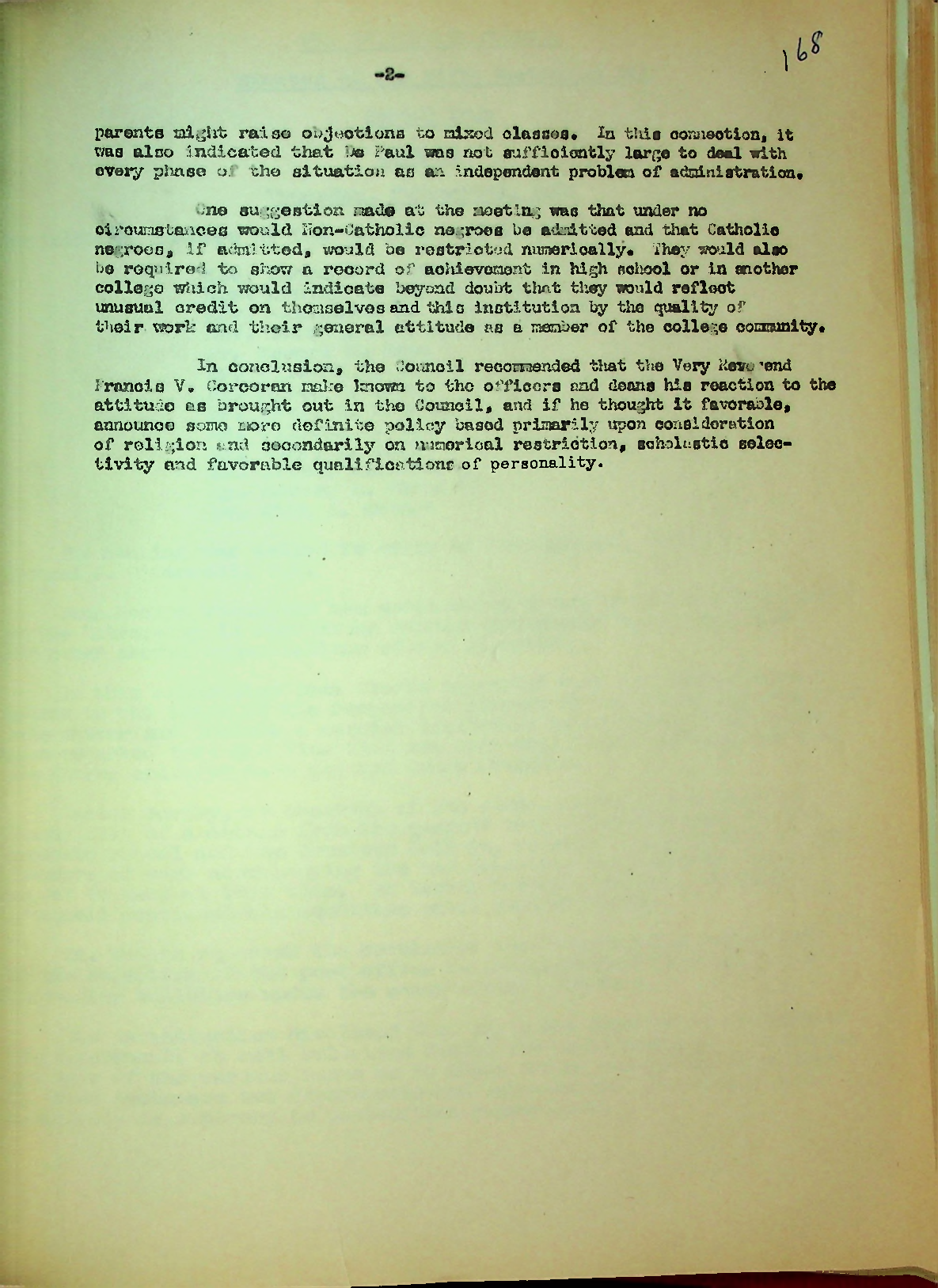

The committee, known as the University Council, consisted of Vincentian priests, members of the presidents’ cabinet and deans of various colleges within the university. In 1934, it also included Rev. Michael J. O’Connell, a future president of DePaul from 1935 to 1944. The council, similarly to the Board of Trustees today, advised then-President Rev. Francis V. Corcoran on the day-to-day needs of the university.

The council recommended that Corcoran respond to the discussion and consider announcing a sanctioned policy, and noted that the absence of one could cause “a real problem” for the university. Corcoran’s response isn’t indicated in the meeting minutes, if he responded at all.

The memo also notes that while some members called for complete refusal of admission to Black students, others had “a more compromising attitude.” The majority leaned toward a case-by-case review of Black applicants and continuing the discriminatory practices already taken by the university.

A nearly hidden history

For John Rury, who was a professor of education at DePaul from 1987 to 2003, the existence of a memo describing how Black students had effectively been barred from attending DePaul didn’t come as a surprise. In fact, he had written about it in the Centennial Essays and Images, a collection of oral and written histories created for DePaul’s 100th anniversary in 1998.

Rury examined DePaul’s longstanding practice of marketing itself as an inclusive institution. “Part of this big project back in the ‘90s was exploring some of that mythology and poking holes in it,” he said.

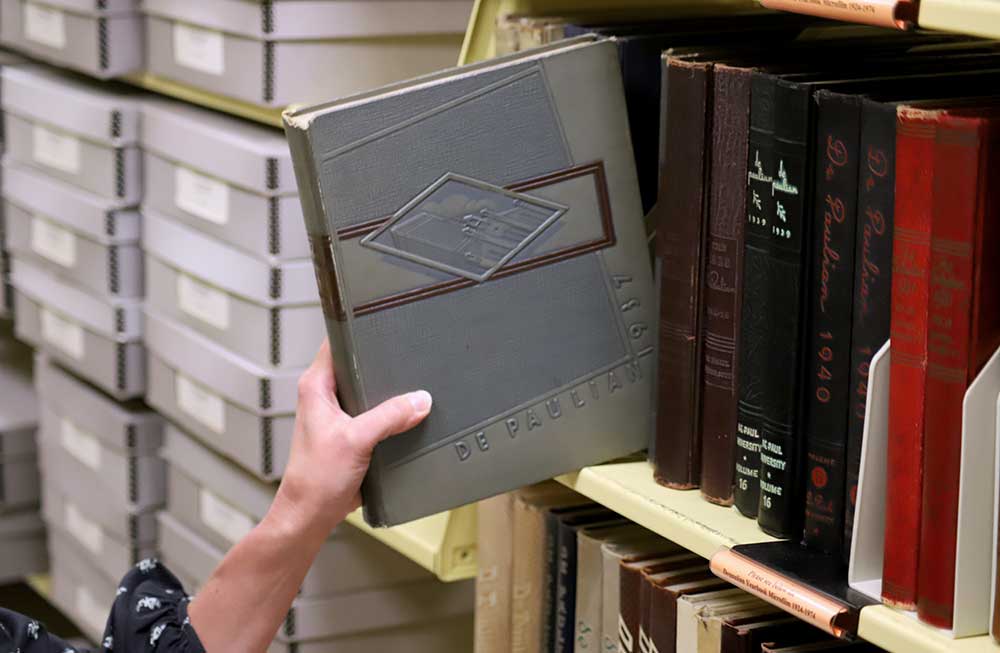

He and a small team of historians and university officials worked to create a comprehensive look at the university’s first 100 years, from student life and athletics to DePaul’s finances. They reviewed historical enrollment data, looked at yearbook photos and pored through correspondences to get a full picture of campus culture and climate. The resulting history, almost 375 pages, includes analyses of DePaul’s student body, especially how underrepresented students were treated as they began to be admitted.

The 1934 memo, Rury and contributor Albert Erlebacher explained in the book, didn’t outright ban Black students from attending, but it instituted incredibly high bars — and hostile environments — for them, effectively creating an almost all-white institution in the process.

These barriers, in addition to the misconception that the University Council, largely made of Vincentian priests and other high-ranking university officials, had about the impact of Black students, are irreconcilable with Vincentian values — a “contradictory nature of DePaul’s emphasis on religious education,” Erlebacher wrote.

While DePaul admitted more than just white students, including small contingents of nonwhite international students mainly from countries where the Vincentians had overseas missions, it used inclusivity as a sound business strategy during a period of financial difficulty, according to Rury. The decision paid dividends during the Great Depression, with Catholic women studying nursing, secretarial or education studies, and Jewish students largely studying at the law and business schools.

DePaul president Rev. Francis V. Corcoran hands out diplomas to graduating students in 1934. That same year, the University Council, which consulted with and advised Corcoran in major policy issues, detailed the ways in which they discouraged Black students from enrolling. (DePaul Special Collections and Archives)

The practices of admitting female and Jewish students “were both by necessity,” Rury said, and not necessarily on the basis of principle. “They needed enrollment as an institution, and they were the stepchild; Loyola was the favorite institution, and DePaul had to scratch its way up.”

The behind-the-scenes decisions that effectively barred Black students seemed less prominent after World War II, according to Rury. Enrollment of nonwhite students, including Black students, increased in the late 1940s into the mid-1950s. According to Rury, World War II was a turning point for race relations on college campuses, including DePaul.

“I think what this shows is that DePaul is not leading the change,” said Rury. “DePaul is very much in step certainly with Catholic America, and that’s largely immigrant America.”

“Catholic America is very a) status conscious and b) status insecure,” Rury added, saying that for an institution that was so enrollment-dependent like DePaul, administrators weren’t sure what reaction white parents would have to the admittance of Black students. “What they’re really saying is that they’re worried if they admit African Americans, it’s going to make the university less attractive to that constituency, because of their status.”

While working on the histories, Rury recalls being told by a Vincentian administrator to leave out sections about the university’s discriminatory behavior against Black students. Rury said that he and other members of the committee pushed back.

Rury said that Richard Meister, then the executive vice president for academic affairs, made the call to include the passages about discrimination. Rury and former Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences Charles Suchar, who co-edited the essay collection, argued in favor of keeping the sections, according to Rury.

Meister said he did not recall experiencing such pushback. Suchar denied that an administrator had a specific opposition to including sections about discrimination at DePaul, and in an email, said that more than two decades later, he doesn't remember any pushback to any part of the drafts of the Centennial Essays, and stands by the integrity and accuracy of the facts documented within it.

"We, the editors of the volume, kept a pretty tight control over the contents and made sure the contributors fact-checked key assertions such as the ones you mention," Suchar wrote. "We stood by those assertions."

“Given the times, and similar policies at other universities that had restrictive administrative means of limiting or controlling enrollment for various groups, I guess I wasn’t surprised,” Suchar added about the documents they fact-checked for the sections, including the 1934 memo. “By contemporary standards, such practices are inexcusable, but so it was back then.”

‘Blacker Than Black’

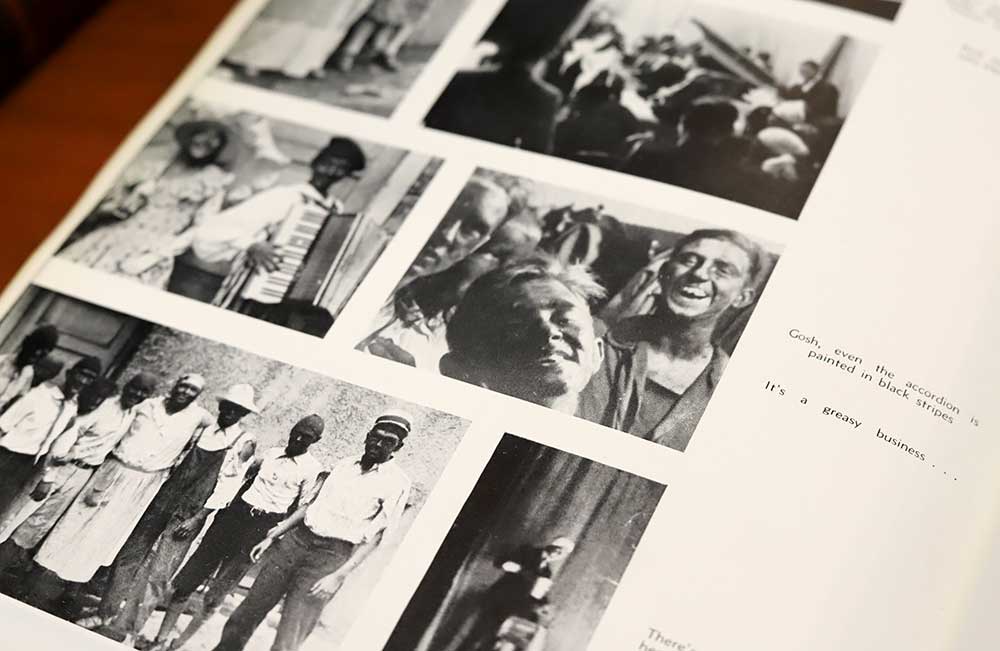

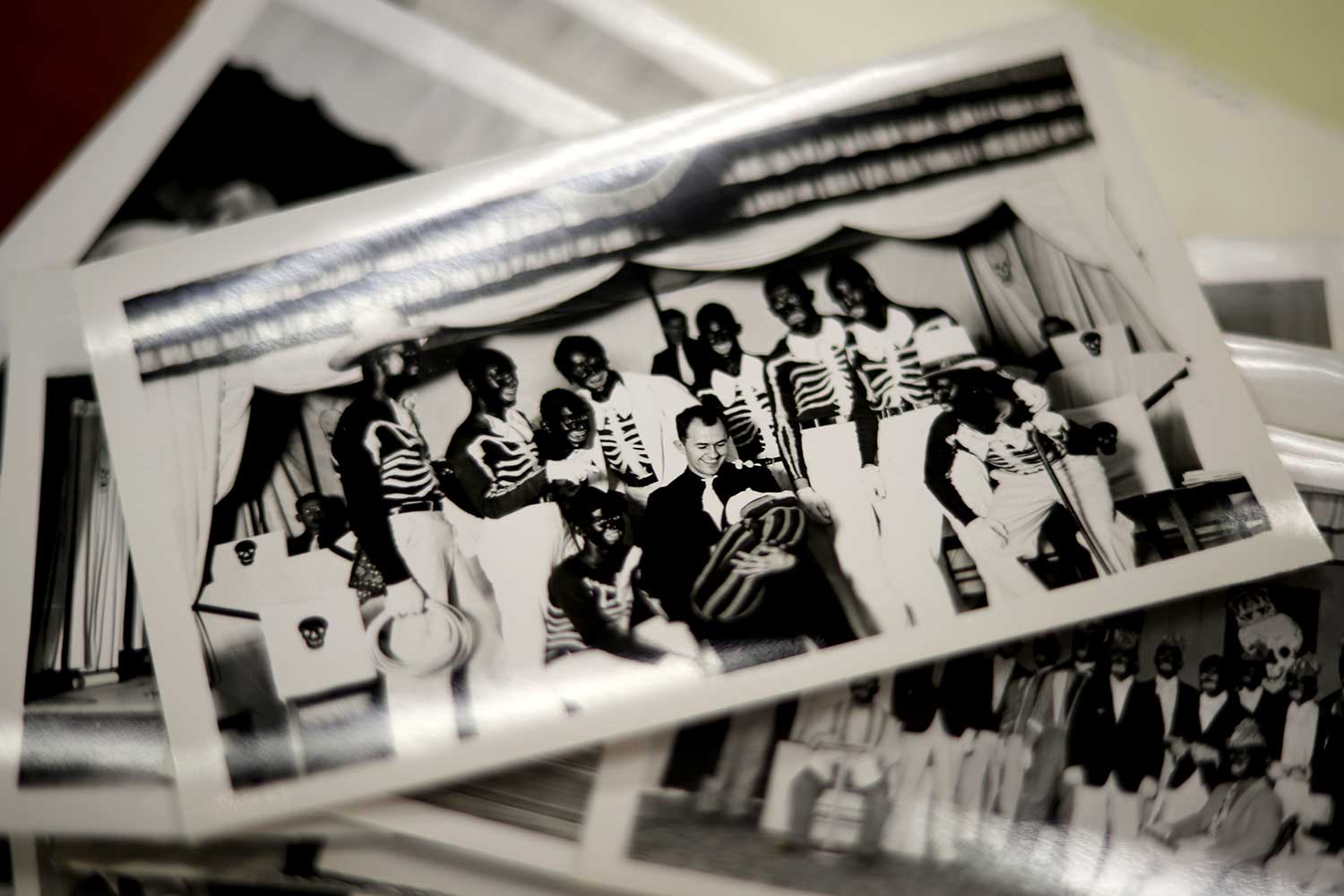

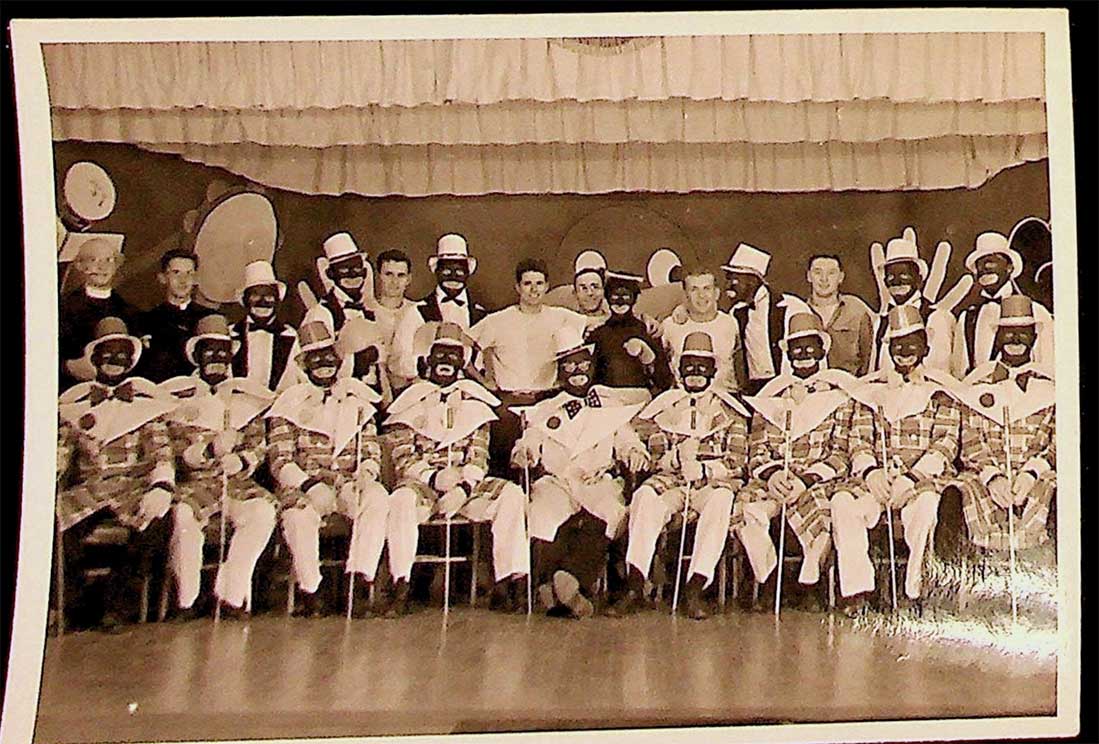

Institutional racism and white supremacy didn’t just manifest in the form of admissions discrimination at DePaul, but extended to entertainment and campus life. For decades, from the start of the university’s growth in 1920 through at least the late 1950s, blackface and minstrelsy were present on the Lincoln Park campuses of DePaul University and, from the 1930s into the 1940s, at DePaul Academy, the all-boys high school that used to occupy what is now Byrne Hall. These performances were examples of a larger culture of white supremacy, and specifically anti-Blackness, not just at Vincentian institutions, but in the country as a whole.

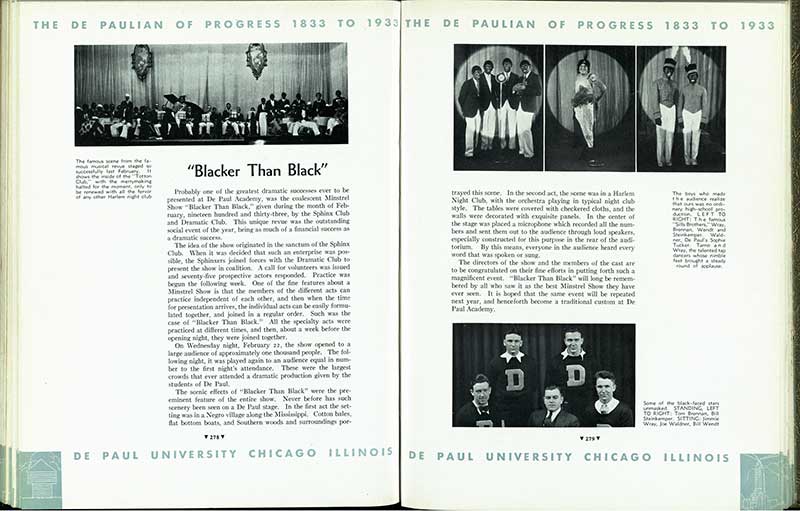

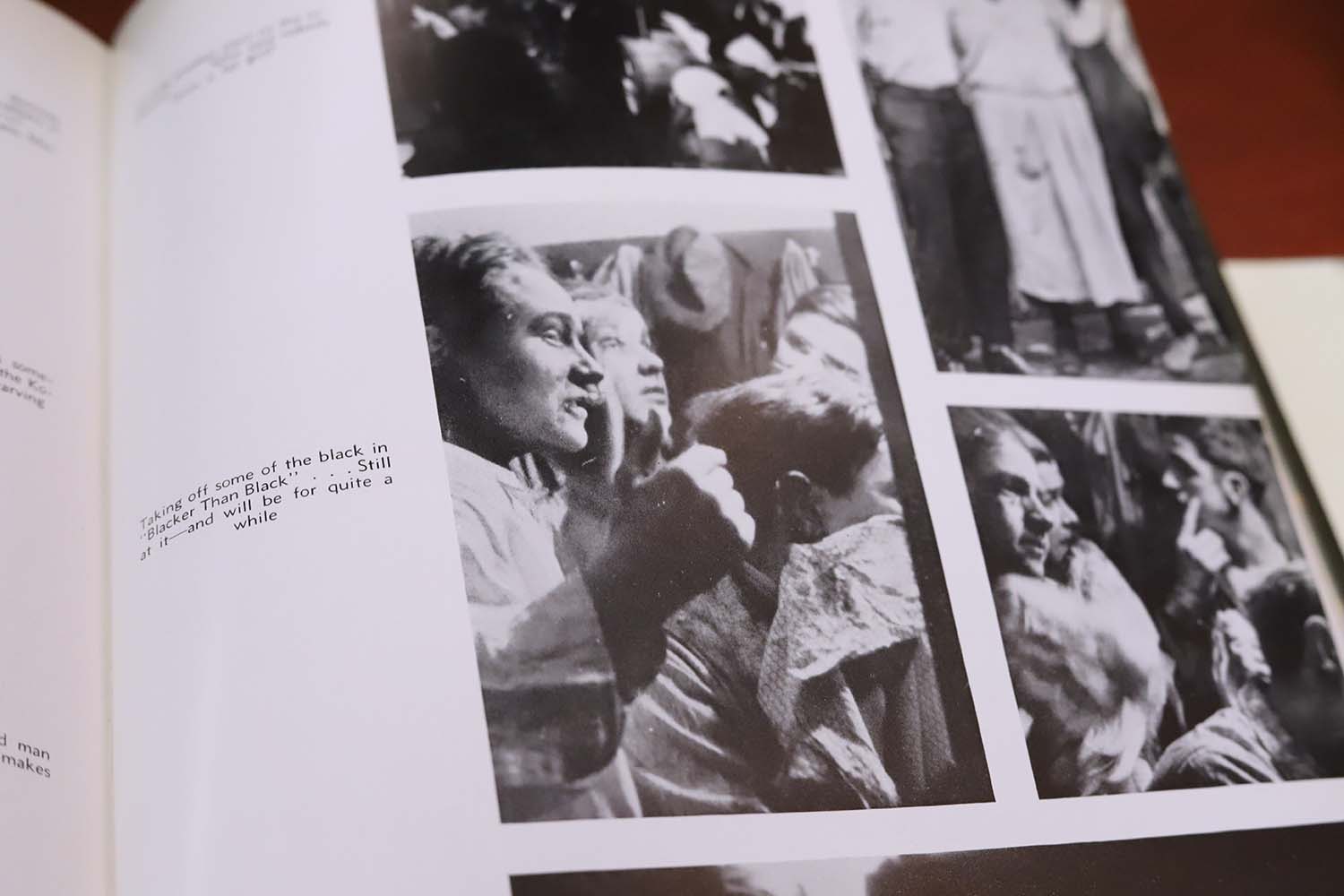

One show at DePaul Academy, in February 1933, titled “Blacker Than Black,” was heralded as one of the preeminent social events of the season. According to the recap in the DePaulian yearbook, nearly 2,000 people attended the performance across two days, with 75 students reportedly wanting to participate. Tickets were 35 cents apiece, or about eight dollars today, with proceeds going toward the athletic fund.

“The unique revue was the outstanding social event of the year, being as much of a financial success as a dramatic success,” the yearbook reads. “These were the largest crowds that ever attended a dramatic production given by the students of DePaul.”

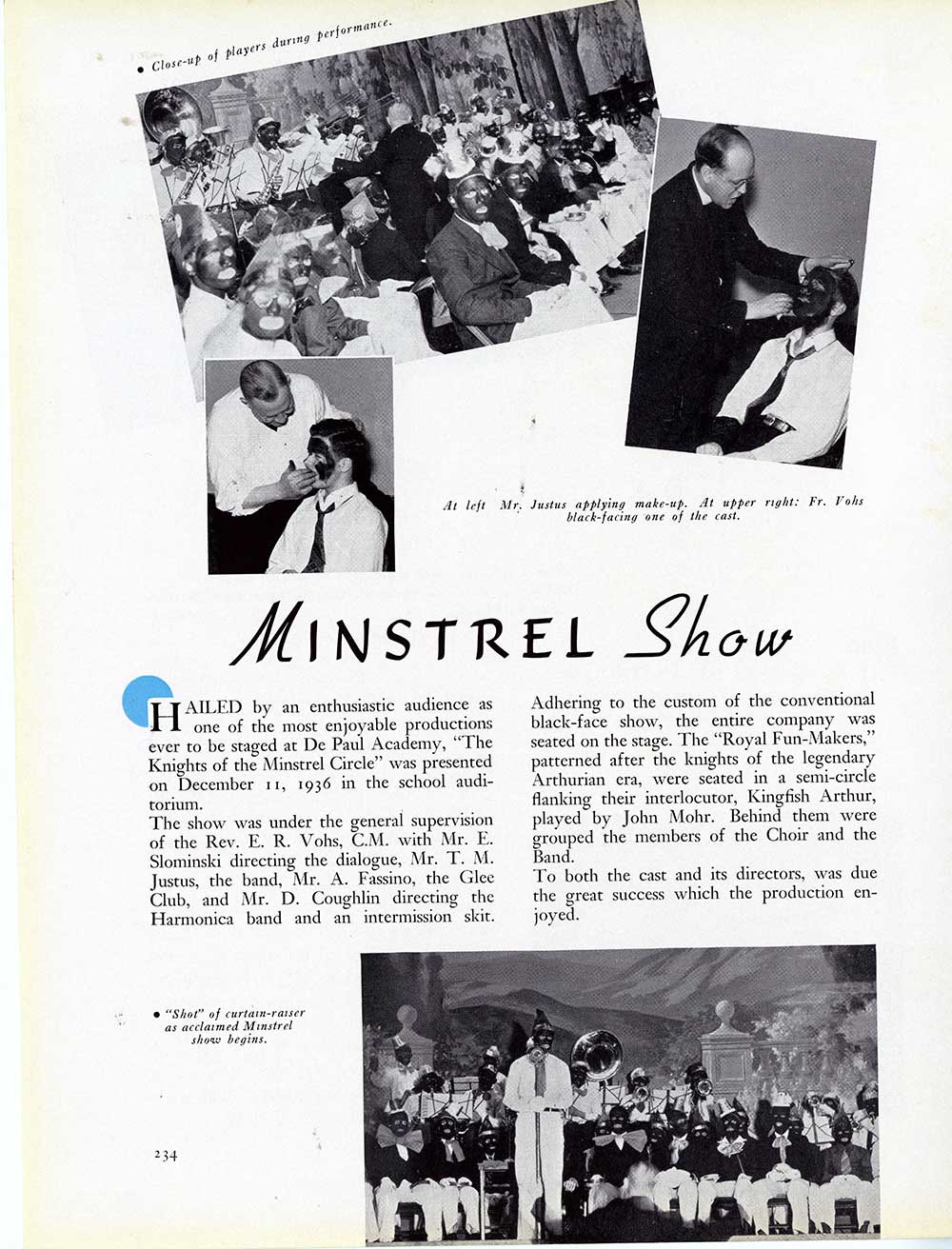

A page from the 1937 DePaulian yearbook shows priests and teachers at the DePaul Academy smearing blackface makeup on students. Materials in the archives show that blackface minstrel shows took place on the Lincoln Park campus of DePaul Academy from at least the 1920s through approximately 1940. (DePaul Special Collections and Archives) [Click through to see additional images.]

Blackface – the act of white actors, mostly men, donning black paint or cork soot in order to caricature and demean Black people as a form of entertainment – has been present in American entertainment for more than 150 years. This is especially true in minstrelsy, a structured variety show that often involved touring companies of white men who performed music and skits in blackface, with the sole purpose of emulating disparaging stereotypes of Black people and culture.

The shows were most popular in Northern industrial cities like Pittsburgh, Boston, Philadelphia, and, of course, Chicago, where exposure to Black people and culture during the Civil War period and immediately after was often limited to working-class white immigrants, who then capitalized on their interpretation of Blackness and the South, writes Eric Lott, author of Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class.

Blackface minstrelsy could sometimes have a starring role in fundraising events, primarily for all-white audiences. Local VFW halls, Rotary clubs, and the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal organization, often held minstrel shows to raise money for their organizations.

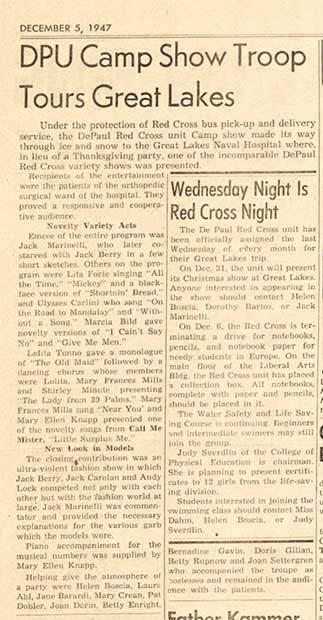

In 1947, the DePaul University Red Cross Club put on a variety show at the Great Lakes Naval Hospital. The show included "a blackface version of 'Shortnin' Bread.'" (The DePaulia)

This normalization of blackface minstrelsy entrenched the performances into social calendars and understandings of race and stereotypes in the 1900s, Lott explains. As more Irish, Italian, Polish and “ethnic white” immigrants began coming to the United States, minstrelsy gave them the opportunity to buy into a unified white identity, particularly in the face of pushback on the basis of ethnicity.

“The minstrel show was, on the one hand, a socially approved context of institutional control; and, on the other, it continually acknowledged and absorbed Black culture even while defending white America against it,” Lott proposes.

Protestants rallied around membership in the Ku Klux Klan, with Chicago having one of the largest and most active chapters for a metro area in the 1920s. For Catholics, whom the Klan rejected, minstrel shows were an insidious way that racism and anti-Blackness revealed themselves.

In the 1933 DePaulian yearbook, DePaul Academy students are shown after a performance of “Blacker Than Black.” The caption beside the photoset reads: “Taking off some of the black in ‘Blacker Than Black’ ... Still at it — and will be for quite a while.” (Cam Rodriguez / DePaul Special Collections and Archives)

“By putting on the blackface mask for the stage, Catholics could be white and American when they took it off,” writes ethnomusicologist George Blake, who studied the connection between white Catholic identity and minstrel performances held by Catholic organizations. These organizations emphasized “religious solidarity over ethnic solidarity, even as they excluded Black Catholics,” Blake adds. Their practices allowed Catholics to “gain a footing” in a country that looked upon them “with suspicion.”

In a collegiate setting, blackface was all too common. While DePaul was staging blackface minstrel shows in the early-to-mid-1900s, so was Georgetown University, another historically Catholic institution. Like DePaulians, Georgetown students staged shows as fundraising events and for special occasions, with institutional backing and a large turnout. And while not Catholic, the University of Wisconsin-Madison also frequently put on minstrel performances and parades for the university and the city.

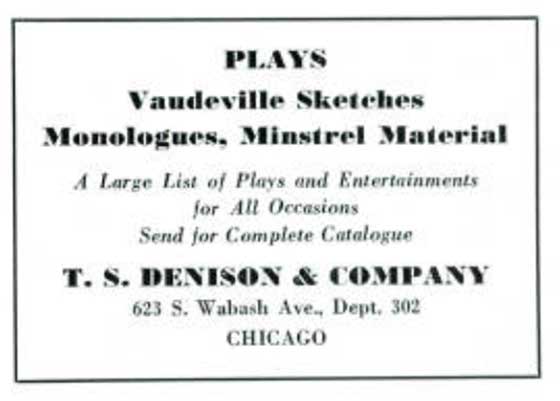

Companies also profited off the rising popularity of minstrel shows in the North. One publishing house, the Chicago-based T.S. Denison & Co., sold catalogs of ready-to-ship materials for minstrel shows, for theater troupes, school plays and other organizations like the Knights of Columbus. Those looking to put on a play could purchase not just scripts and musical scores, but a variety of props and makeup — including soot and greasepaint for blackface — as well as posters and paper cut-outs for programs and advertisements. Advertisements for T.S. Denison appeared in DePaul yearbooks, advertising a full mail-order catalog “for all occasions.”

Often, organizations with some arts experience would write their own minstrel shows, riffing on the body of work popularized by publishers like T.S. Denison. Minstrel shows became even more popularized by films like D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, which inspired an additional wave of the Ku Klux Klan, and shows like Amos N Andy.

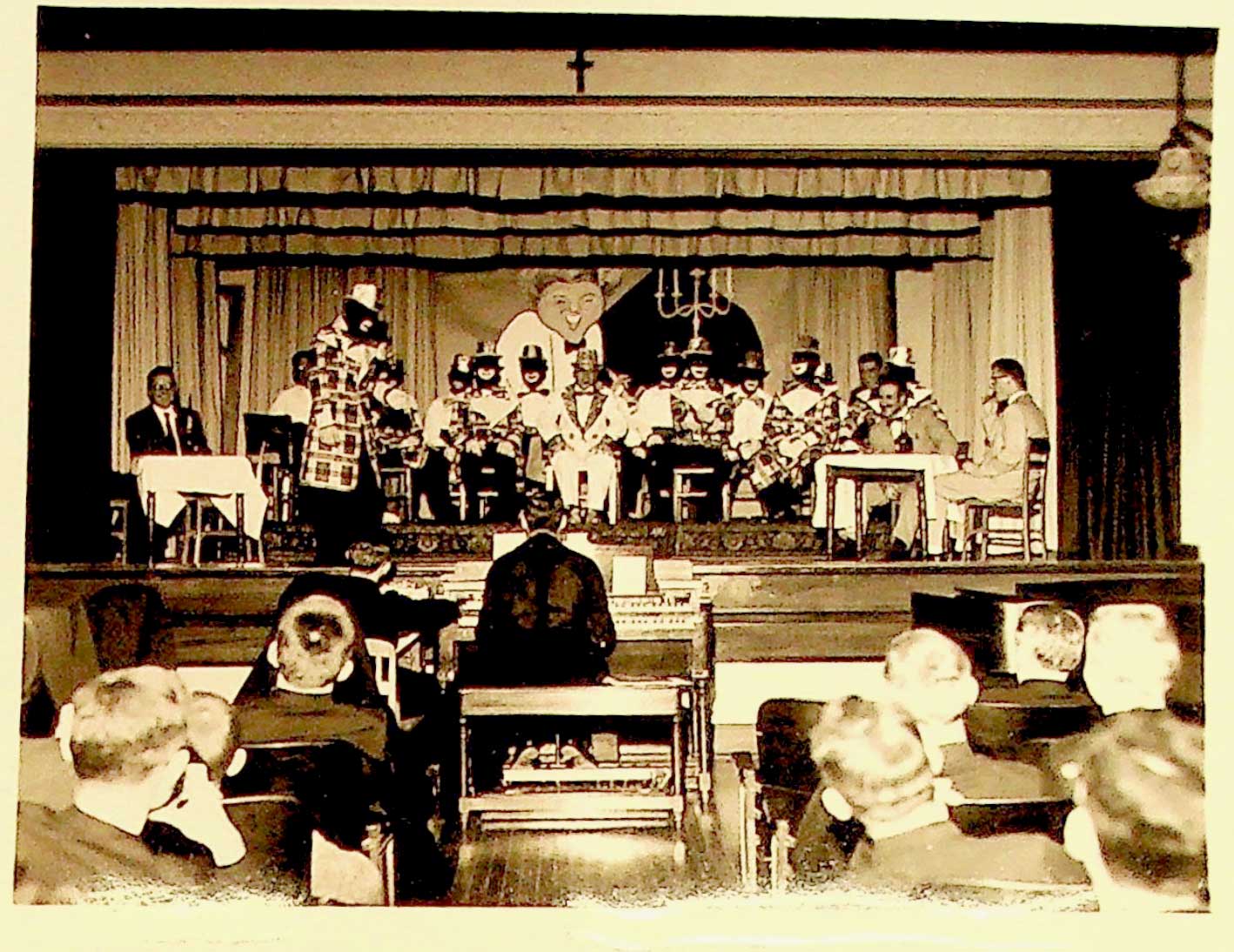

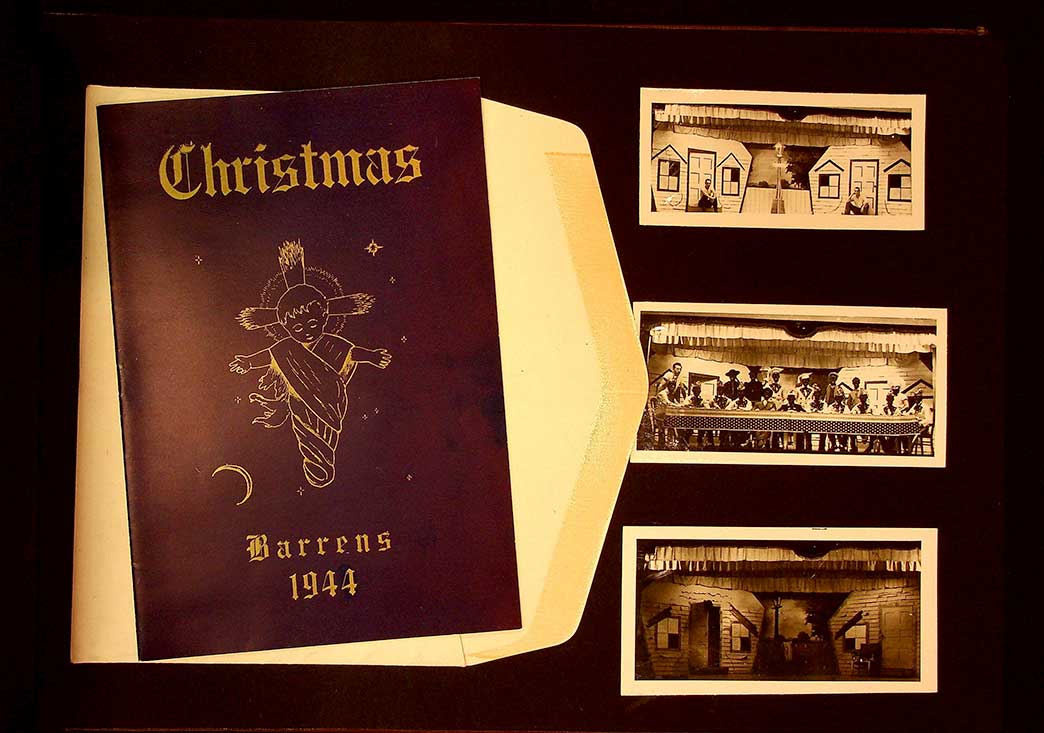

In the historic home and training ground of the Vincentians, at St. Mary’s of the Barrens Seminary in Perryville, Missouri, about a two-hour drive from St. Louis, priests and trainees of the Congregation of the Mission wrote, acted and performed in minstrel shows into the early 1960s, putting the shows on within the seminary.

They also put on an annual Christmas minstrel show, including the performance as part of a multi-day, faith-driven celebration for a largely white audience.

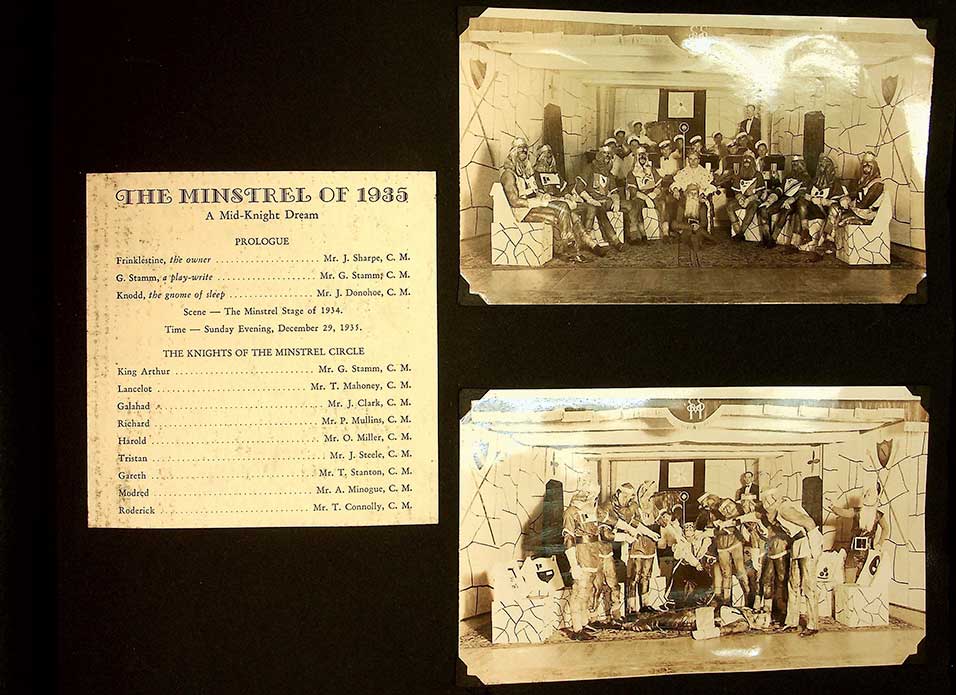

In one 1935 show, “A Mid-Knight Dream,” Vincentians in blackface donned Arthurian outfits and dressed as “the Knights of the Minstrel Circle,” likely a reference to The Knights of the Golden Circle, a pro-slavery, pro-Southern secret society that wanted to create a circular human trafficking system between St. Louis, Texas, Mexico, Cuba and Southern cities.

A scrapbook page displays the program and scenes from "A Mid-Knight Dream" and “Knights of the Minstrel Circle” at the St. Mary’s of the Barrens seminary in 1935. A show with many similarities was later performed at DePaul Academy as “Knights of the Minstrel Circle” in 1936. (Cam Rodriguez / Vincentian Archives)

The following year, in 1936, the “Knights of the Minstrel Circle,” a show with similar themes, structure, layout and cast, was performed at DePaul Academy with school-aged children in blackface overseen by Vincentian priests.

Original documents in DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives, including photos, scrapbooks and seminary publications, show evidence for performances at St. Mary’s of the Barrens stretching from 1909 to 1961, with shows at DePaul Academy spanning approximately 1932 to the 1940s. At DePaul University, evidence of blackface minstrel shows in The DePaulia and the DePaulian and Minerval yearbooks indicates that minstrel shows hosted by student organizations, including sororities, happened on and off campus from 1920 well into the late 1950s, after DePaul began admitting Black students in higher numbers.

Blackface minstrel performances were often hailed as being the highlight of the year’s theatrical productions in The DeAndrein, a student publication written and produced by Vincentians studying at St. Mary’s of the Barrens, with consistent mentions of minstrel shows from the start of the archival collection in 1930 until the mid-1950s.

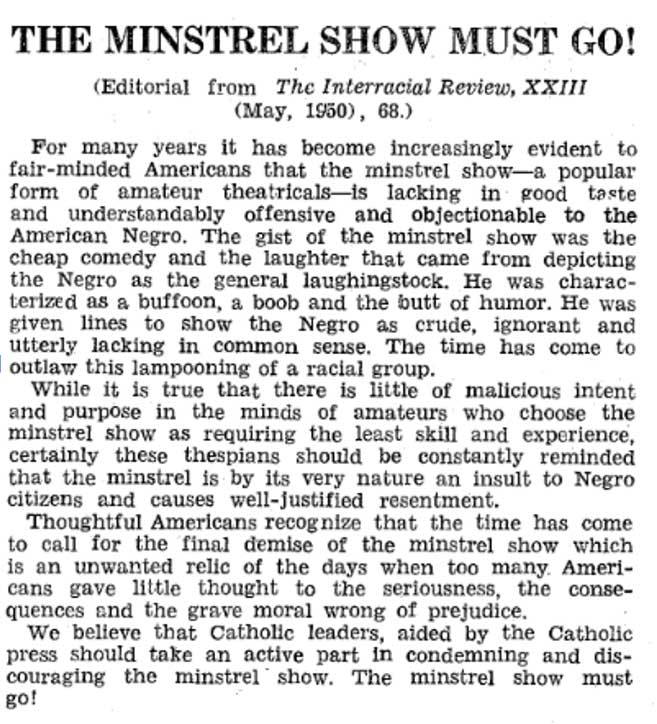

Not all Vincentians agreed with minstrelsy’s popularity. In November 1951, The DeAndrein published an editorial from the Catholic Interracial Council of New York’s publication The Interracial Review, stating that “the minstrel show must go” due to its offensive nature and that Catholic leaders should take a stance against it. Despite that, in January 1952, a full writeup and photos of the minstrel show from Christmas were published, starting with a tongue-in-cheek jab at the editorial.

A 1950 editorial reprinted in 1951 in The DeAndrein, a student publication at the St. Mary’s of the Barrens seminary, called for an end to minstrel shows due to their offensiveness. The school continued to put on minstrel shows for another 10 years. (The DeAndrein / Vincentian Archives)

Traditions from the seminary carried into DePaul Academy had high school-aged boys performing in minstrel shows produced by their teachers. Faculty involved in the performances included Fr. Edmund Vohs, the principal of DePaul Academy in 1936. While faculty assisted with the performances, based on yearbook accounts, shows were planned and run by a collection of student organizations. These organizations included the “Sphinx Club,” and the high school’s drama club and choir, all of which Fr. John Egan, who attended DePaul Academy from 1931 to 1934, belonged to as a student.

A statue of Fr. John Egan stands outside the DePaul Student Center. Egan was a student at DePaul Academy from 1931 to 1934, and was a member of multiple clubs that put on blackface shows, although he is not identified in any photographs of those performances. Egan went on to become a leader in the civil rights movement, calling for housing equality and speaking out against programs like urban renewal. (Cam Rodriguez and 1934 DePaulian yearbook)

Fr. Egan, whose legacy is honored at DePaul in the form of a statue and the Egan Office, was a Chicago diocesan priest and longtime civil-rights organizer who pushed for equal treatment of all races in the Catholic Church, spoke out against urban renewal and housing inaccessibility, and was one of the clergy who marched alongside Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, Alabama.

There are no explicit images of Fr. Egan in the yearbook participating in minstrel performances or in blackface, though he is listed as being a member of the student organizations that put on those shows while he attended DePaul Academy, and he appears on pages highlighting minstrel shows in the DePaulian yearbook. All of his activism, Egan Office director John Zeigler says, “doesn’t exonerate” Fr. Egan from what racist things he may have been engaged with as a teenager, but it adds to the complexity of his work.

“Even if he was complicit, he changed a whole hell of a lot somewhere along the line. Even if he was that guy, even if he was one of the blackface [performers], and I'm hoping and praying that he wasn't that, at some point, he made a huge change in his own life and how he looked at this work,” Zeigler said.

To Zeigler, this larger interrogation of DePaul’s history stands as an example of Sankofa, a Ghanaian principle of looking to things in the past in order to move forward in the present.

“I think it just puts another focus on what racial equity and social justice looks like,” Zeigler said. “I think about this whole thing around Sankofa — ’to go back in order to move forward.’ How do these stories have us, as we look back and look at what’s the damage that it’s done, how do we move forward with that? So, it’s a sort of Sankofa process of healing.”

DePaul president Rob Manuel speaks at his “Designing DePaul” event on January 26. (Michelle Edwards / 14 East)

President Rob Manuel, who joined DePaul from the University of Indianapolis on Aug. 1, 2022, said he was saddened by the evidence of behavior departing from the Vincentian values touted by the university, including the 1934 University Council memo, as well as evidence of discrimination and minstrelsy.

“I am a history major, and recognize the value of knowing the things that happened in our past, especially as they require us to craft a future to plan moving forward,” he said in an interview with 14 East in November, when presented with the memo and evidence of blackface at different Vincentian institutions. “I'm saddened by all of this, as anyone would be, but can see it as a way for us to realize how to live into the mission.”

“Addressing the painful history”

In August 2021, an email from the Office of the President, then under Manuel’s predecessor, A. Gabriel Esteban, arrived in the inboxes of DePaul students, faculty, staff and some recent alumni.

“Addressing the painful history of slave ownership within the Congregation of the Mission,” the subject line read.

In 300 words, it promised atonement and reconciliation from the dark history of Vincentian priests owning and enslaving African Americans. In particular, it noted the participation of Bishop Joseph Rosati, who was among the first Vincentian priests to arrive in the United States. He founded the Vincentian order in Perryville, Missouri, and ultimately became the bishop of St. Louis.

But in 300 words, the email also created distance.

“While Bishop Rosati is clearly connected to the Vincentians who sponsor DePaul University, he has no direct connection to DePaul University. In fact, his actions took place more than 75 years before the founding of our university,” read the email, which was signed by Esteban and Fr. Guillermo “Memo” Campuzano, the vice president for Mission and Ministry. “However, our university is part of the Vincentian family, and we therefore acknowledge that these facts are connected to the history of our sponsor.”

The email explained that spaces named after Bishop Rosati – Room 300, a reading room on the third floor of John T. Richardson Library, as well as a collection of Vincentian records in Special Collections and Archives – were to be renamed. A later community-wide email, in December, announced that the university would launch a task force to further investigate the relationship between Vincentians and slavery.

Director of the School of Public Service and geography professor Euan Hague poses for a portrait in Room 300. Hague is a member of the task force established by the university to address the Vincentians’ relationship with slavery. “I think one thing that has maybe slowed the task force down is a determination to get things right.” (Cam Rodriguez)

Euan Hague, a DePaul geography professor and director of the School of Public Service, who sits on the DePaul Task Force to Address the Vincentians' Relationship with Slavery — the group mentioned in the email — remembers the moment he found out the room name would be changed. He rushed to campus to document the displays of Vincentian history that had hung on the walls, to document what would likely be removed in the wake of the announcement.

He photographed exhibits — reproductions of Vincentian materials that had been hanging in the room — that had already been taken down, as well as the signage outside.

Hague researches postwar commemoration of the Confederacy, revisionist American histories and white supremacy. The timing of the dedication of the room to Bishop Rosati and the rapid decision to strip the name both caught his attention.

The Rosati Room, now known as “Room 300,” had its name changed in August 2021 following the discovery by the Archdiocese of St. Louis that Bishop Joseph Rosati enslaved people. The paint has been scraped off a sign on the third floor indicating the location of the room, and taped over on a directory sign near the elevator banks on each floor. (Cam Rodriguez)

“Why is this happening now?” he said about the original dedication of the room. “Why in 1993 are we putting up a room to honor Rosati?’”

Now, the room’s walls are largely smooth and undecorated; the sign outside reads “Room 300,” with no other adornment. A single sign, a recent addition, describes the history of the renaming process of the room, including when and why the room had been dedicated.

A monument on DePaul’s Lincoln Park Campus, just outside Arts & Letters Hall, lists the names of Congregation of the Mission members involved with DePaul Academy and University, including Francis V. Corcoran, Michael J. O'Connell, Daniel McHugh, Alexander P. Schorsch, and Martin V. Moore, and DePaul Academy principal Edmund Vohs. (Cam Rodriguez)

The task force, which transitioned from an ad hoc task force to a full committee earlier this year, is made up of faculty, staff and students, with a research focus specifically on the Vincentians of the Congregation of the Mission’s relationship with enslavement and the slave trade. This includes reexamining DePaul and the Vincentians’ history and digging into primary documents, mainly between the Vincentians’ establishment in Perryville in 1818 and the end of the Civil War in 1865.

“The task force I set up during my presidency focused on important issues — both to me personally and the university community at large,” former President A. Gabriel Esteban wrote in an email to 14 East. “Working with the Vincentians and the university community, we addressed the early recommendations from the task force as they were identified.”

The history of the Vincentians’ relationship to slavery is hidden in plain sight, according to Morgen MacIntosh Hodgetts, another member of the task force. MacIntosh Hodgetts has worked as an archivist for nearly 20 years with DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives, handling and processing records transferred from the Vincentian archives in Missouri.

“The Vincentians, from their perspective, believe they’ve never hidden this, and that they’ve written about it,” she said. “And they certainly have.”

For over 20 years, Morgen MacIntosh Hodgetts has processed and handled materials in DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives, including materials transferred from the Congregation of the Mission in Perryville, Missouri. (Cam Rodriguez)

In Church and Slave in Perry County, authored by two Vincentian priests, the Vincentian ownership of enslaved people is included with the Congregation of the Mission’s history and development. But reproductions of primary documents, like receipts and ledgers, are relegated to a footnote and an appendix.

“The readership of a publication like this from the 1980s is very small, and it’s not widely distributed,” MacIntosh Hodgetts said. “When you read that, it’s very much a fixture of a time where we’re still in this white paternalistic, colonial … kind of mindset. So, it’s not hidden, but there’s context there that isn’t lifted out as it should be.”

What must be done?

Brittan Nannenga, a former DePaul archivist who left the university in 2022, said the existence of racist documents in the university’s archives wasn’t a surprise to her or other archivists, and it shouldn’t be a surprise to the task force or Vincentian leaders.

“Being on this task force, and within the archives, they’ve been aware that those records exist and that something should be done, and have been for a while pressing for something to be done,” said Nannenga.

Brittan Nannenga, who had been an archivist in DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives since 2019 and left in summer 2022, says that archivists have a responsibility to collect and maintain all history about an institution, not just the parts that make it look good. (Cam Rodriguez)

MacIntosh Hodgetts sat on the task force, providing insight into archival materials and sharing what the Vincentians had in their collections, including the documents, ledgers and receipts of sales of people that Vincentians enslaved.

“When people engage with the actual documents and see handwritten receipts of individuals being bought and sold, it does a hell of a lot more to somebody,” MacIntosh Hodgetts said.

According to Fr. Memo Campuzano and a statement from the university, based on the research that the task force has conducted so far and recommendations made from the group, some changes will be made on campus to better reflect the full history of DePaul and the Vincentians, including the renaming of multiple spaces and more funding put toward efforts furthering diversity and inclusion.

Though the committee was recently formalized from an ad hoc status, MacIntosh Hodgetts said that at some point, the research and recommendations on the specific topic of Vincentians and slavery will eventually have to come to a close.

“This task force work has to end, and then another group would have to take up the more recent history,” MacIntosh Hodgetts said. “That’s the nature of the task force — it isn’t like a committee or working group, a task force has a discrete end point.”

Multiple members confirmed that because of the task force’s charge and scope, it has not looked into more recent ties to white supremacy in the university’s history.

That scope should change and widen, according to Fr. Memo, not just for the sake of the university, but for the Congregation of the Mission as a whole.

“If we don’t do that, we’ll be living in denial,” he says. “This is critical for our identity ... so we need a game plan to be sure that there is nothing in our present time that anybody in the future will need to apologize for. We need to research all archives, to be sure that we recognize and identify all practices that should be denounced.”

As part of his DEI recommendations following his January “Designing DePaul” event, President Manuel announced funding for a “Presidential Scholar” for the upcoming school year to “increase our ability to understand DePaul’s connections to racism.” This, alongside funding for additional archival displays and a renewed focus on DePaul’s history, makes MacIntosh Hodgetts optimistic.

“I think the current climate is certainly one where it's a lot more receptive to doing research that's closer to home and closer to the more recent past,” MacIntosh Hodgetts said. “We, here in the archives, remain interested to help people access these materials and make them available and point them to places in the archival records that can help draw these connections. That’s our commitment, and it’s always been that.”

Institutions seeking reconciliation

As campuses across the country reckon with racist elements of their history and complicity in white supremacy, different paths forward have been forged for reparations and reconciliation.

The labor of enslaved people enabled the growth of the Vincentian order, which arguably provided resources that helped establish DePaul. While the university had no direct involvement with slavery, other universities, particularly some Catholic ones, did.

Georgetown University, one of the oldest Catholic universities in the country, is actively reconciling with its history of enslaving and the sale of 272 women, children and men in 1838, after a working group began researching the history in 2015. Georgetown’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation is made up of members across the university community, specifically acknowledging the descendants who were harmed in the process, though some descendants have made it known that more engagement is necessary.

After student protests, Georgetown renamed two of its buildings in 2015 to honor Anne Marie Becraft, one of the first Black Catholic nuns, and Isaac Hawkins, the first person listed on a manifest of enslaved people. The buildings previously had been named for people, both priests, who were responsible for the sale of humans whom they enslaved and sold.

Tia Noelle Pratt is a sociologist of religion and the assistant vice president for mission engagement and strategic initiatives at Villanova University, which was founded by Augustinian Catholics in 1842. Faculty, staff and students at Villanova have been closely looking at its history, and specifically at relationships that allowed the university to prosper in Pennsylvania.

Renaming buildings and structures, Pratt says, addresses issues of representation and empowerment on campuses, as buildings are highly visible and ubiquitous in campus life.

Georgetown’s decision to rename two buildings, Pratt says, “makes perfect sense: to honor and encapsulate the history, to recognize that history and continue to recognize that history, but not to honor the ones who orchestrated the sale, but the ones who felt the brunt of it.”

Many Catholic schools likely have elements of their history where they overlooked the contributions or labor of people of color, including at Villanova, according to Pratt.

At Villanova, graduate student Angelina Lincoln dug through archival materials and found records of William Moulden, a Black man who had been an indentured servant. Unlike enslaved people, indentured servants in principle could work off their debt and, in some cases, earn their freedom. However, their rights were extremely limited, and they were often poorly treated. After the Moulden family had secured their freedom, they were acquainted with the Augustinians that ran the university and eventually willed their property to Villanova itself, with the agreement that Mr. Moulden’s wife and daughter could continue to live on the land for the rest of their lives.

The land, which was later sold, allowed the Augustinians to financially sustain the growth of the university at a cash-strapped time, but Mr. Moulden and his family went largely unacknowledged in the university’s canon and campus. Now, there’s a building on campus named after the Moulden family, according to Pratt, and “there’s more work that’s going to be done around that.”

Pratt also looks at ways that Catholic institutions can act to commemorate those in Catholic history who are overlooked. Loyola University in Maryland renamed a dorm building after Sister Thea Bowman, the first Black Franciscan nun who, due to her work advocating for equality and empowering Black Catholics, has some Catholics pushing for her canonization.

Members of DePaul’s task force are taking a similar step. Belden-Racine Hall, a residence hall on campus, will be renamed to commemorate Aspasia LeCompte, a woman enslaved by Bishop Rosati who sued him for her freedom. He sold her in response, and she subsequently sued her new enslaver and won her case.

The decision to rename Belden-Racine Hall was announced by Manuel soon after his “Designing DePaul” event following the approval of the Board of Trustees, according to Fr. Memo. The process to select LeCompte as the namesake had started in January 2022, and had previously been approved by outgoing president Esteban before pausing due to the presidential search.

Fr. Guillermo Campuzano, vice president of Mission and Ministry, has been a Vincentian priest for decades. “Can we open our eyes and become aware if there is anything we are doing, promoting, or permitting, that generations of the future will be ashamed of, and embarrassed by? Because this… wow.” (Cam Rodriguez)

“We want to make her a visible symbol of our collective resistance to racism … may that renaming [be] the symbol of healing resistance,” Fr. Memo said about choosing LeCompte. “Those movements in humanity that embrace the best of all of our collective being … in connecting that with the best of our Vincentian mission, the unquestionable, unnegotiable, undeniable recognition of the dignity of every human person.”

Though there are no known paintings or photos of Aspasia LeCompte, Fr. Memo said there will be opportunities for students and the university community to contribute to murals on campus in remembrance of her. One space where students will be able to commemorate that history will be in “a student-driven art display” in Belden-Racine Hall, according to a statement sent to 14 East from the university.

Previously, Room 300, or the former Rosati Room, was going to be renamed after LeCompte. Choosing a new name for the room is in progress, though Fr. Memo suggested it “will be dedicated to all the people that were enslaved by the Vincentians,” with space for exhibits and displays about history. Another building, a “Vincentian-owned residence” at 2210-2212 N. Racine Ave. known as the Rosati House, will also be renamed.

DePaul political science associate professor and interim associate provost for DEI Valerie Johnson has pushed for inclusive dialogue and curricula for her entire career. Most recently, she successfully passed a Faculty Council resolution to require the use of euphemisms in the place of racial epithets in the classroom, as well as changes to language indicating grounds for dismissal for employees. (Cam Rodriguez)

For Valerie Johnson, DePaul political science associate professor and Endowed Professor of Urban Diplomacy in the Grace School of Applied Diplomacy, this is an all-too-familiar discussion. “Naming buildings, that’s fine,” she said. “But there’s got to be more than that, and there has to be an apology and acknowledgement of harm, and a form of redress.”

As interim associate provost of diversity, equity and inclusion, Johnson oversees and recommends institutional changes to curricula, works with the college diversity advocates, and supports recruiting and retaining a diverse faculty. As a member of DePaul’s task force, she has debated the idea of what reconciliation looks like to not just settle the past, but to also not carry the harm into the present.

The essential components of an apology that Johnson identifies are lacking from DePaul’s original acknowledgement of the Vincentians’ involvement in slavery, because the acknowledgement denies the financial and social connections between it and white supremacy. But Johnson holds out hope for a proper apology and commemoration of the university’s full history.

“People’s lives were absolutely erased,” Johnson said. “I’d like to see a discussion on how the Vincentian identity needs to be reinterpreted in light of this information.”

The university aims to rename both Belden-Racine Hall and Room 300 in May, according to Fr. Memo, coinciding with plans for an “interfaith celebration of repentance, resilience, accountability” and “forgiveness.” The ceremony, which will be held on DePaul’s Lincoln Park campus in the Student Center, will focus on reconciliation, with the head of the Western Province of the Congregation of the Mission visiting the university to apologize on behalf of the Vincentians.

A few weeks after the interfaith celebration, there will be two public ceremonies to recognize the renaming of each space, a process that Fr. Memo said will be a precedent for the future of new spaces and buildings on campus.

“This is introducing a conversation. How are we naming? What names? For what reason?” he added. “Usually the naming of buildings at DePaul was under Vincentian historic figures. Now we are introducing another concept, which is very powerful.”

Murals by art instructor and Vincentian Br. Mark Elder decorate 25 posts underneath the Fullerton 'L' stop that cuts through the Lincoln Park campus, commemorating the university's history from its beginning in 1898 to now. Included in the faculty- and student-led art project are murals honoring the university's first Black female graduates, a law graduate and civil rights activist and the 50th anniversary of a sit-in by the Black Student Union. (Cam Rodriguez)

In his “Designing DePaul” speech to the university community in January, Manuel indicated that additional funding would be provided for fellowship and staff positions to further university-wide DEI efforts, and that the school would support recommendations put forth by the Black Equity Initiative and the task force.

“We, the Black community at DePaul, the faculty, staff, and students, had the recommendations that were ignored previously,” Johnson said. “I feel that by making DEI a top priority, that it suggests a significant change in the attitude around DEI. I think previously, it was very difficult to argue that there was a priority when you are ignoring a whole community.”

Part of the speech, and Johnson’s ongoing work in her time at DePaul, addresses student retention and graduation rates — particularly for Black students. Black and Latine students routinely have lower rates of retention and graduation than other groups on campus, with the four-year graduation rate for Black students sitting at 44% in the 2021-2022 school year, according to data from DePaul’s Institutional Research and Market Analytics department, compared to 55% for all students.

First-year retention, or the measure of how many students remain after their first year at DePaul, was lowest for Black students, according to data presented by Manuel that was released in January. Only 75% of Black students were reported to have stayed through their first year in 2021-2022, compared to 87% of white students.

Manuel said he wants to directly address DePaul's shortcomings in engaging with and listening to its Black students, faculty and staff. He also said he plans to address ongoing issues of retention and satisfaction among faculty, as well as concerns that DePaul's programs are not diverse enough given the changing racial makeup of its student body.

“It's not very difficult to see the differences in achievement in those spaces. This is the case with faculty representation, with staff representation, and we need to solve for this, not just understand and engage,” Manuel said during his speech in January. “This is only one representation of a problem that we will solve. This is one of our biggest obstacles to relevance and value going forward.”

When asked how discriminatory admissions practices and a culture of white supremacy, which enabled blackface minstrel shows for decades on campus, may still affect the DePaul community today, the university did not respond directly to the question of ongoing impact. 14 East received a statement via email that read in part:

“Both these instances [of discrimination and minstrelsy] represent times when DePaul did not live up to its Catholic, Vincentian values. DePaul has a long history of engaging questions of equity and developing new initiatives to support our diverse community of learners. The university is fully committed to continuing its work to make DePaul a unified and equitable institution.”

The Western Province of the Congregation of the Mission in Perryville, Missouri, when asked about the harm of the practices and shows that were largely facilitated by Vincentians, sent 14 East a statement that read in part:

“It is saddening that DePaul was not immune to the attitudes and practices around race that were the rule rather than the exception in American higher education at that time, especially at private schools in the South and Midwest. Similarly and unfortunately, minstrel shows were also relatively common during the timeframe indicated in your reporting, as attitudes about race were not nearly as evolved in the U.S. as they are today. Our current provincial leadership was not aware of the referenced minstrel shows at DePaul Academy and St. Mary’s of the Barrens.

“While these attitudes and practices were sadly prevalent in the U.S. at that time, they are not an accurate indication of who the Vincentians are as a community, nor do they coincide with the charism of our founder, St. Vincent de Paul. We look back on those actions with great sadness, but we are also very proud of the work we have done to serve the poor in marginalized communities throughout our 200 years in the United States, including communities of color in many cases.”

St. Vincent's Circle sits just outside the Richardson Library, which contains the Vincentian Archives. It features a bronze statue of the 17th century saint conversing with two contemporary students. Inscribed in the ground are the words "education," "community," and "dignity." (Cam Rodriguez)

In his “Designing DePaul” speech, Manuel further indicated his feelings about revelations that blackface minstrelsy occurred on campus and by Vincentians, and about discussions of discrimination against prospective Black students.

“There are times when we’ve corrected that course, but there is also evidence that we have continued work to do,” he said. “I am deeply sorry for those moments. And I recognize there are still remnants of racism on our campus. Our job is to eliminate it.”

Cam Rodriguez is a journalist and DePaul alum, and was formerly managing editor at 14 East. She began researching and reporting this story in 2021, which you can read more about here. Have questions, comments or tips related to this story? Get in touch with Cam at heycamrodriguez@gmail.com.

Correction: In a previous version, Fr. Egan was listed as being a Vincentian priest; he is actually a Chicago diocesan priest. Additionally, Brittan Nannenga was listed as being a member of the task force; she only served as a University Archivist. These have been corrected.

![In 1958, the DePaul University College of Physical Education class of sophomores put on a “show in the minstrel fashion, compete [sic] with blackface and white gloves.” (The DePaulia)](http://fourteeneastmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/1958_0321_DePaulia_MinstrelShow.jpg)

NO COMMENT