I spent two years researching and reporting on the legacy of the Vincentians and its relationship with DePaul’s history — here’s what I learned.

Content warning: This piece includes photos of blackface minstrelsy.

For a complete bibliography, scroll to the end or click here. (Though I’d recommend reading the whole thing.)

I never intended to work on a story like this, or for this long — I quite literally stumbled onto it, and I’m so grateful I did. A year into the pandemic, in March 2021, while researching in DePaul’s archives for a different story, I came across pages and pages of blackface, minstrelsy and racist displays at DePaul Academy, on DePaul’s Lincoln Park campus.

I knew the photos were shocking, but I also knew it was evidence of a larger culture and period of history, for Chicago, the country, DePaul and the Vincentians — and that it was an opportunity for accountability and reconciliation. So, from there, I jumped into research and got digging.

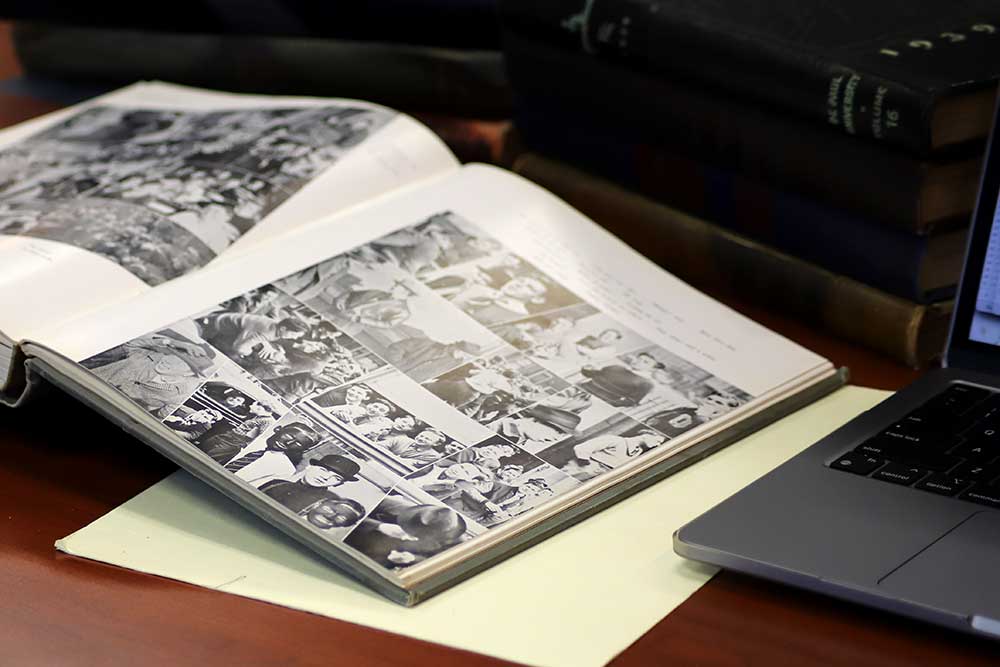

The 1933 DePaulian yearbook, with photos of high school students in blackface, sits open on the reading room table with other yearbooks that gave insight into DePaul’s student life at the time. (Cam Rodriguez)

The problem? Campus was closed, the city was reeling from wave after wave of COVID-19, and I had no idea where to start when it came to searching through DePaul’s archives. Months later, at the end of 2021, I began digging through the digital collections of DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives, looking for more context and evidence of how deep white supremacy ran in DePaul’s early history.

What I found from cursory searches in between Zoom classes and up-until-3-a.m. deep dives included mentions of blackface minstrelsy present in DePaul’s archival collections of The DePaulia, as well as multiple yearbooks that documented both DePaul University and DePaul Academy, the all-boys high school on DePaul’s campus from 1898 until 1968, which I knew very little about at the time.

There were a lot of parts about DePaul’s history that I hadn’t known about until this project began. I’m a big fan of “always reading the plaque” — that is, always reading the signs posted outside buildings, parks, monuments and more — and as I continued my digging into the context around the images I found, I became more attuned to the pieces of the university’s history that hide in plain sight around campus, including parts of DePaul’s history intertwined with the Vincentians. Another part of that Vincentian history was revealed via email in August 2021: that Bishop Rosati, one of the first Vincentians in the United States, enslaved people.

A monument on DePaul’s Lincoln Park Campus, just outside Arts & Letters Hall, reads “1816-2016: celebrating the 200th anniversary of the arrival of the Vincentian fathers and brothers in the United States.” (Cam Rodriguez)

From the arrival of the Congregation of the Mission (the formal name of the Vincentians) and their establishment in Perryville, Missouri, in 1818 until the end of the Civil War, priests were enslaving and selling whole families and building their congregation with that labor; the first person recorded as being purchased by Bishop Rosati was an 8-year-old boy.

This revelation, which I later learned was an open secret in the Congregation of the Mission that had been acknowledged multiple times before, pushed me into reporting and moving on this information that I hadn’t known how to contextualize.

When we were able to return to campus in person, I made many trips to the library and to Special Collections, amassing a pretty impressive cart of boxes filled with yellowed onionskin papers and photos over the course of months. The process was solitary and isolating, but with headphones and the archivists to keep me company, I cycled through sheaves of enrollment data, album after album of photos, stacks of yearbooks, oversized boxes of artifacts and records, musty leather-bound books and piles of correspondences, with the goal of highlighting larger, systemic patterns of racism and discrimination at the start of the university’s history and in the Congregation of the Mission.

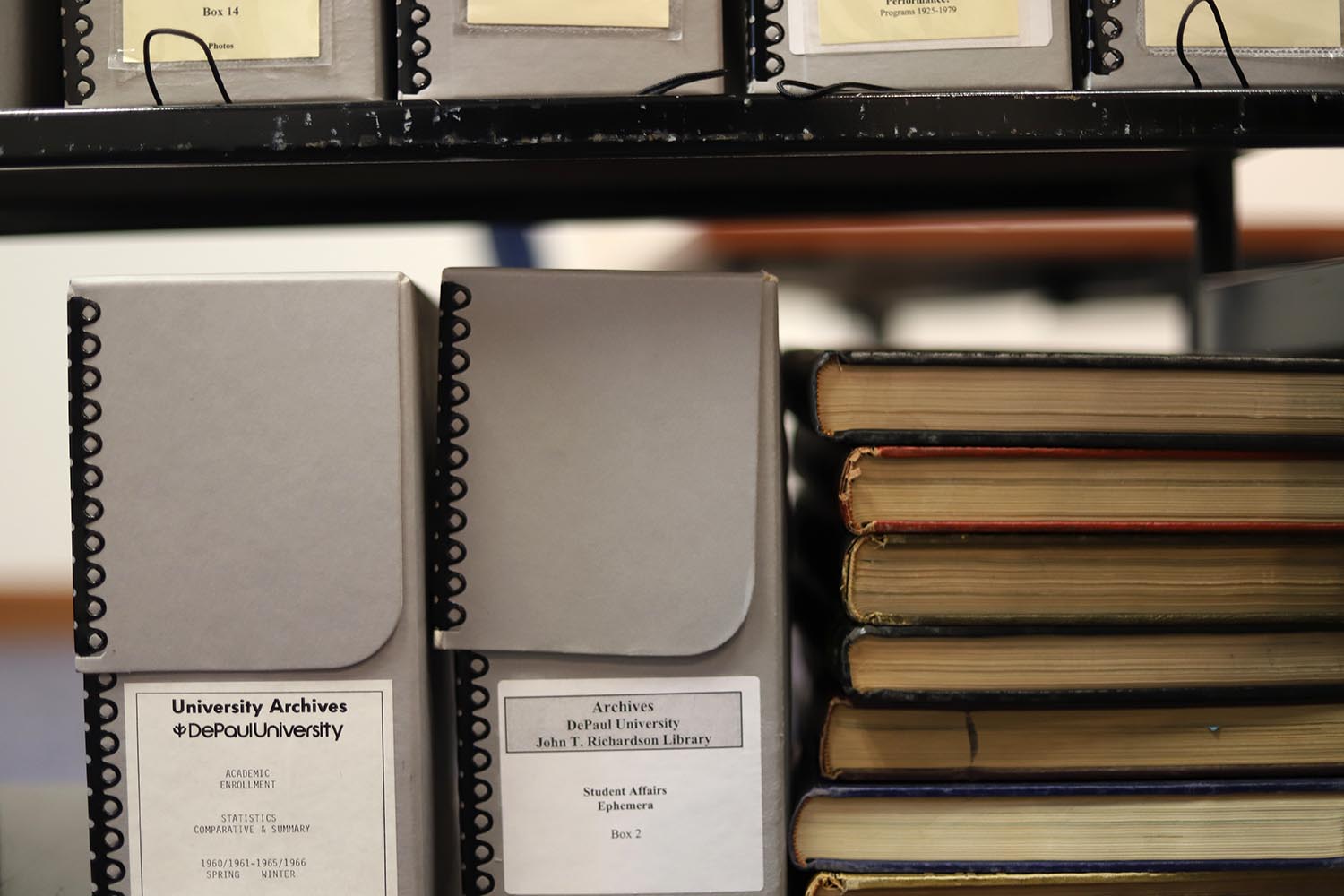

After only a few weeks of research in the archives, I was upgraded to a larger cart in order to accommodate the thousands of original documents across different collections and decades that supported this piece. (Cam Rodriguez)

It was not fun. Nothing like this ever is. Opening an envelope to find fifty photos of priests in blackface, only to have the next be a hundred photos of the same, will never not be jarring. As much as I love when research and history — and how extremism, history and acknowledgements of that history — intertwine, the process was overwhelming and hardening. It felt like every corner I turned opened up another rabbit hole of white supremacy and its manifestations with Vincentian institutions. In the months leading up to graduation, I felt pessimistic and slighted about the institution I was about to get a second degree from and had spent five years growing to love.

In my last quarter at DePaul, in Spring 2022, I undertook an independent study alongside photojournalist and professor Robin Hoecker, who documented the cycle of Black student protests at Penn State while she herself was a student. Our discussions about the primary documents, how to frame them, and what context was needed to provide historical and cultural insight were the bedrock of this reporting process, further supported by the scholarship and work of others. During the independent study quarter, I spent multiple days a week in the archives, surrounded by documents and oversized boxes; quickly, my cart was upgraded from a small to a larger one, as the scope of my research changed based on what I read and watched for class.

After a six-hour day in the archives, I’d come back to my apartment and turn on breakdowns of Amos ‘n’ Andy, a wildly popular radio and, later, television, show that was one of the most normalized broadcasts of audio and visual blackface in the early/mid 1900s, or a video essay about Birth of a Nation, one of the first major motion pictures that featured blackface and racial violence. It was screened at the White House, where Woodrow Wilson claimed it was akin to “writing history with lightning”; it later sparked a second resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

When working with sensitive material, I spoke with not just Hoecker about how and why we wanted to display the images, but with others who had handled similar archival material for their stories about deeply racist histories, including Logan Jaffe of ProPublica and Simon Levien of The Harvard Crimson. Both Logan and Simon published meticulous stories of the racist history of places, with corresponding archival material displayed, and both recommended providing as much context as possible for the images that are included in a story — including adding descriptive captions, showing the images as objects instead of isolated (an approach that Logan took with a series about racist memorabilia in the New York Times) and creating a sort of buffer to keep people from being blindsided.

For the story, I sorted through and scanned hundreds of photos of priests-in-training in blackface within the Vincentian Archives, which previously had been named for Bishop Rosati until the announcement in August 2021. (Cam Rodriguez)

Those approaches, particularly the point about not showing things in isolation, were ones that I was deeply focused on while doing research and taking photos. In addition to the scans of the documents and photos — of student life, of blackface, of enrollment data — I made sure to also capture the photos themselves, if not for use in the story, then to show me the magnitude of the research I had been combing through.

With the thoughts about contextualizing primary source documents as much as possible bouncing around in my head, I used that principle to guide my reporting and who I spoke with. I didn’t want this story to be a flat piece about blackface being found in the yearbook, because that wasn’t the point. Early on, when talking with sociologist Tia Noelle Pratt, based at Villanova, about the photos, she asked me something that I frequently returned to months later in my notes: “Is this about the photos, or is this about what the photos represent?”

It was about what they represented, not about the pictures themselves, and my goal as a journalist would be to figure out how to convey that point, along with other documents, over decades’ worth of DePaul and Chicago’s history.

“Is this about the photos, or is this about what the photos represent?”

Through the process, I was able to have illuminating and invigorating conversations with researchers, professors, priests, mentors, administrators, journalists, students and community members that reminded me just how critical the work was. This included months of rewarding — but intense — conversations with the members of 14 East’s all-student staff, who worked tirelessly on the editing, fact-checking and production of the piece, bringing their different experiences and skills to the table to help me best convey a fuller history about DePaul and the Vincentians that needed to be told.

Everything about the process felt isolating, but after I was able to share my work with confidence, I was reminded how grounding community-centered journalism is, especially on stories as unwieldy as this. Putting in the work, and sharing the work with the community, is at the heart of this piece.

The reading room, located on the third floor of the John T. Richardson Library in the Lincoln Park campus, was where I often spent multiple days a week researching, scanning and digging through yellowed pages of documents and stacks of glossy photos. (Cam Rodriguez)

With that said, from the very start, it was clear to me that I had been coming across objects in DePaul’s collections that had been seen by likely very few people — or had been seen by many, but not in a long, long time. I kept meticulous notes about where I found everything, not just to help out the fact-checkers here at 14 East, but so it could be shared, especially with DePaul’s Task Force to Address the Vincentians’ Relationship With Slavery, which has been active since August 2021, and with other researchers and students interested in exploring institutional racism and its manifestations in their schools.

Since I started work on this piece, DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives has even put a “harmful content notice” on their homepage, something that other schools have done with items in their collection that are racist or graphic, and something we did with the piece I reported. My hope is that with the publishing of a full bibliography, this story can not just shed light on previously unacknowledged history, but also act as a tool for others.

In Fall 2022, I shared this research with members of DePaul’s administration for the first time, walking them through a slice of the photos and the 1934 admissions memo. I was grateful for the amount of time that Fr. Memo Campuzano, the vice president of Mission and Ministry and a Vincentian priest, gave me, and the amount he shared about his ministry — and the conflict that had entered his life from revelations about Vincentian slaveholding and, now, blackface minstrelsy.

After my conversation about the findings with the soon-to-be-inaugurated president Rob Manuel in November 2022, he reportedly went soon after to the archives, where he viewed some of the documents, including the primary documents being combed through by the task force about people that the Vincentians enslaved and sold. In January, Manuel publicly acknowledged DePaul’s involvement with blackface minstrelsy and admissions discrimination, making DEI a priority for his administration. As a now-alum, I can only be optimistic about the change that may be coming to DePaul with regards to diversity and inclusivity, true to its mission, in whatever form that takes.

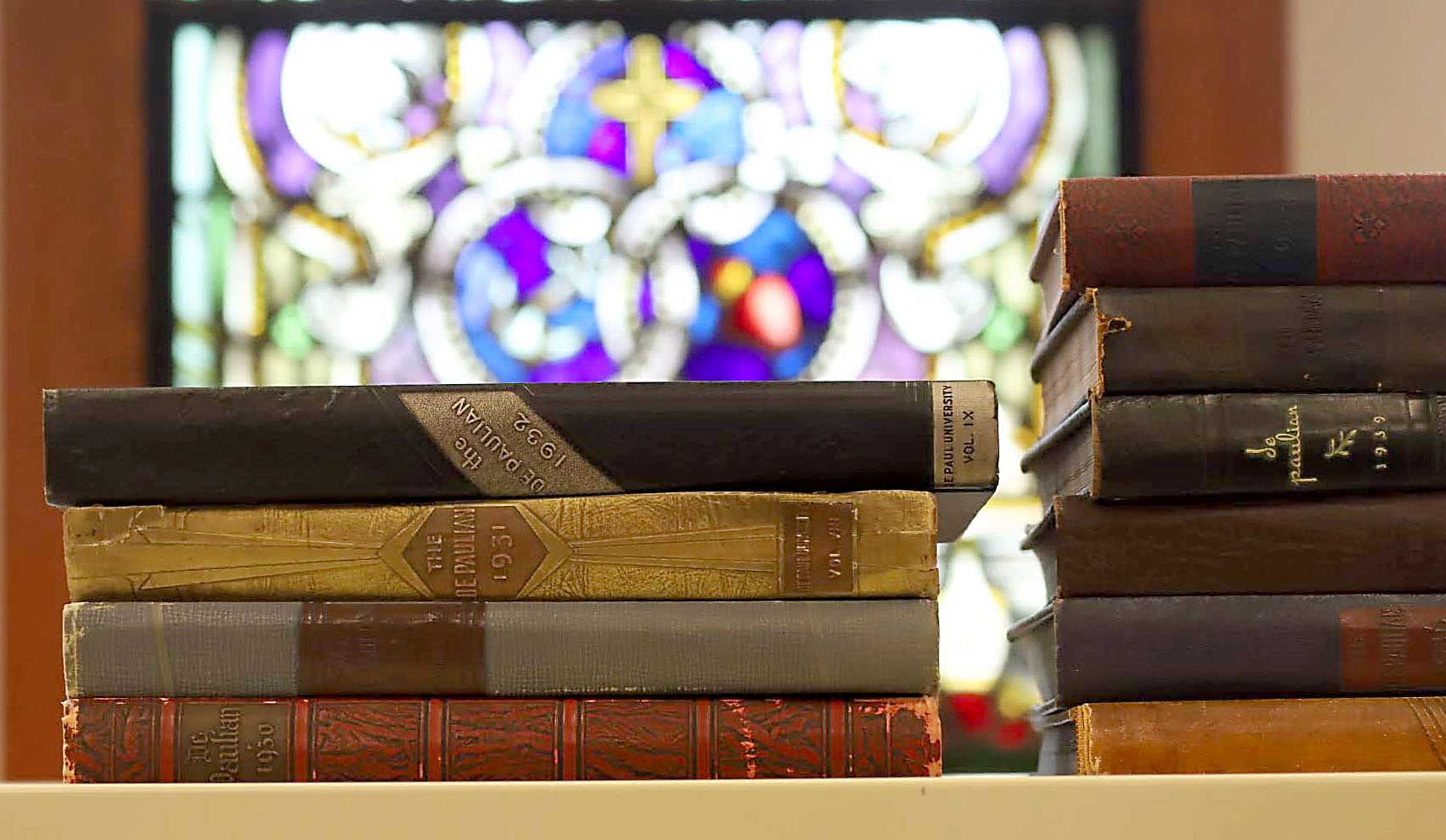

A stack of DePaulian yearbooks sit on a cart in the Special Collections reading room. (Cam Rodriguez)

This research extends far past just one piece or project; I’ve felt deeply connected to it, especially based on my experiences of racism and discrimination and the experiences of my friends at Catholic educational institutions, and I hope that investment shows. I still feel fondly about my time at DePaul, and I hope that this is a step in the right direction for acknowledging the past, bringing it into the present, and reconciling — not just reckoning — with that history.

Bibliography

Archival material

DePaul Special Collections and Archives had a massive impact on the brunt of the work I did and the amount of primary documents I came across. Thank you to the entire staff past and present, especially Derek Potts, Morgen MacIntosh Hodgetts, and Brittan Nannenga, for your assistance, experience and moral support.

Vincentian Archives

Saint Mary’s of the Barrens boxes

Rev. Edward Furlong photograph collection

DePaul Academy boxes

The DeAndrein archives

DePaul University Collections

Enrollment data

Student Affairs archives

The DePaulia archives

Black Student Union archives

DePaul History archives

Correspondences

University Minutes

Yearbooks, including The Minerval andThe DePaulian

Photography/Student Life archives

Scholarly research

In order to provide context and understand the historical settings of this, I turned to the body of work amassed by researchers and scholars at other institutions and at DePaul; their expertise helped me understand the magnitude and impact of the primary documents. While not everything is directly referenced in the piece, if you’re interested in learning more about racism at educational institutions, minstrelsy and popular culture, white supremacy in the Midwest and beyond, and more about DePaul’s history, these are a great place to start.

Books

“Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy & The American Working Class,” by Eric Lott, 1993.

“Sundown Towns,” James W. Loewen, 2005.

“DePaul University Centennial Essays and Images,” edited by John Rury and Charles Suchar, 1998.

“An Alley in Chicago: the ministry of a city priest,” Margery Frisbie, 2002.

“Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop,” Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen, 2012.

“Burnt Cork: Traditions and Legacies of Blackface Minstrelsy,” ed. Stephen Johnson, 2012.

“Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism,” Eric Lott, 2017.

“Church and Slave in Perry County,” Stafford Poole and Douglas Slawson, 1986.

“The American Vincentians: A Popular History of the Congregation of the Mission in the United States 1815-1987,” John Rybolt, 1988.

Articles

“The Legend of A-N-N-A,” Logan Jaffe, ProPublica Illinois, 2019.

“The Crimson Klan,” Simon Levien, The Harvard Crimson, 2021.

“The Story Behind the Failed Minstrel Show at the 1964’s World Fair,” Vicky Gan, Smithsonian Magazine, 2014.

“Every Time I Turn Around: Rite, Reversal and the end of blackface minstrelsy,” Jim Comer, Ferris State University Jim Crow Museum.

“Archdiocese’s research into history with slavery reveals three bishops, priests as slaveowners,” Jennifer Brinker, St. Louis Review (Archdiocese of St. Louis), 2021.

Journal pieces

On blackface minstrelsy

“Love and Theft: The Racial Unconscious of Blackface Minstrelsy,” Eric Lott, 1992, Representations.

“A strictly American institution: Neil O’Brien, blackface minstrelsy, and the invention of white Catholic identity,” George K. Blake, 2019, Popular Music.

“The Knights of the Golden Circle: a Filibustering Fantasy,” C. A. Bridges, 1941, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly.

“Black Politics but Not Black People: Rethinking the Social and "Racial" History of Early Minstrelsy,” Douglas A. Jones, Jr, 2013, TDR.

“Black English in Early Blackface Minstrelsy: A New Interpretation of the Sources of Minstrel Show Dialect,” William J. Mahar, 1985, American Quarterly.

“"Jim Crow," "Zip Coon": The Northern Origins of Negro Minstrelsy,” Alan W. C. Green, 1970, The Massachusetts Review.

““Simple Devices are Always Best”: An Examination of the Amateur Play Publishing Industry in the United States,” Kevin Byrne, 2014, The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America.

On Catholic slaveholding and Vincentians

“Slavery and the Shaping of Catholic Missouri, 1810-1850,” Kelly L. Schmidt, 2022, Missouri Historical Review.

“American Slavery, American Freedom, American Catholicism,” Maura Jane Farrelly, 2012, Early American Studies.

“"Though Their Skin Remains Brown, I Hope Their Souls Will Soon Be White": Slavery, French Missionaries, and the Roman Catholic Priesthood in the American South, 1789-1865,” Michael Pasquier, 2008, Church History.

“The Northern Catholic Position on Slavery and the Civil War: Archbishop Hughes as a Test Case,” Charles P. Connor, 1985, Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia.

“Jesuit Education And Slavery In Kentucky, 1832—1868,” C. Walker Gollar, 2010, The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society.

“The Decline and Fall of Saint Mary's of the Barrens: A Case Study in Contraction of An American Catholic Religious Order - Part One,” Richard J. Janet, 2001, Vincentian Heritage Journal.

“Missionaries Extraordinaire: The Vincentians from Saint Mary's of the Barrens Seminary,” Patrick Foley, 2001, Vincentian Heritage Journal.

“Three Pioneer Vincentians,” John Rybolt, 1993, Vincentian Heritage Journal.

“The Era of Boundlessness at St. Mary’s of the Barrens, 1818-1843: A Brief Historical Analysis,” Richard J. Janet, 2012, Vincentian Heritage Journal.

On Catholic higher education

“Meeting Multiple Demands: Catholic Higher Education for Women in Chicago, 1911-1939,” Ann Marie Ryan, 2009, American Catholic Studies.

“Gender, Coeducation, and the Transformation of Catholic Identity in American Catholic Higher Education,” Susan L. Poulson and Loretta P. Higgins, 2003, The Catholic Historical Review.

“A Half-Century of Change in Catholic Higher Education,” Philip Gleason, 2001, U.S. Catholic Historian.

On Black parishioners in the Catholic Church

“Black Catholics in Nineteenth Century America,” Cyprian Davis, 1983, U.S. Catholic Historian.

“The Holy See and American Black Catholics. A Forgotten Chapter in the History of the American Church,” Cyprian Davis, 1988, U.S. Catholic Historian.

“Beyond Parish Boundaries: Black Catholics and the Quest for Racial Justice,” Karen J. Johnson, 2015, Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation.

“Another Long Civil Rights Movement: How Catholic Interracialists Used the Resources of their Faith to Tear Down Racial Hierarchies,” Karen J. Johnson, 2015, American Catholic Studies.

“Black Catholics in the United States: A Historical Chronology,” Ronald L. Sharps, 1994, U.S. Catholic Historian.

“We've Come This Far by Faith: Black Catholics and Their Church,” Diana L. Hayes, 2001, U.S. Catholic Historian.

Films and media

“Amos ‘n’ Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy,” dir. Stanley Sheff, 1983

“Exterminate All The Brutes”, Part 2: “Who The F*** Is Columbus?” created by Raoul Peck, 2021

In addition to the scholarship above, I’m also grateful for the professors, historians, journalists and other students I spoke with for this piece who shared so much work of their own with me over the phone, over Zoom, and in person:

Dr. Tia Noelle Pratt, Villanova University (creator of the #BlackCatholicsSyllabus)

Euan Hague, DePaul University, Geography department, director, School of Public Service

John Rury, University of Kansas; formerly of DePaul University’s College of Education

Brittan Nannenga, School of the Art Institute of Chicago; formerly of DePaul’s Special Collections and Archives

Morgen MacIntosh Hodgetts, Vincentian Archivist, DePaul University Special Collections and Archives

Simon Levien, Harvard University

Logan Jaffe, ProPublica

Robin Hoecker, DePaul University, Journalism program

Valerie Johnson, DePaul University, Political Science department

John Zeigler, The Egan Institute, DePaul University

Fr. Memo Campuzano, C.M., Vice President for Mission and Ministry, DePaul University

And for everyone who worked with me on the production of this story:

Mariah Hernandez, fact checker

Robin Hoecker, visual editor

Bridget Killian, managing editor

Amy Merrick, faculty advisor and editor

Monique Mulima, editor-in-chief

Billie Rollason, fact checker

Cam Rodriguez is a journalist and DePaul alum, and was formerly managing editor at 14 East. Her piece, on DePaul's history and legacy of white supremacy, can be read here. Have questions, comments or tips related to this story? Get in touch with Cam at heycamrodriguez@gmail.com

NO COMMENT