It was the morning of my fifth birthday party, and my mother struggled to get me dressed. She pulled a spaghetti strap black dress over my head, and the pastel-colored triangles and rectangles that covered the front became soaked with my tears as I protested. I hated the way the straps felt against my skin. But even more, I hated the way the dress exposed my chest.

I spent the rest of the day running around my party with my arms crossed, covering my chest. I didn’t understand exactly why I was so uncomfortable at the time, but I knew I felt a sense of shame and embarrassment with the way I looked.

Now, I can pinpoint the root cause of those feelings because I feel them every day and understand them all too well.

My fifth birthday party was the first time I felt gender dysphoria.

Gender dysphoria describes the discomfort people may feel when their sex assigned at birth differs from their gender identity. The American Psychological Association (APA) and the American Medical Association (AMA) both recognize gender dysphoria as a documentable form of psychological distress and support the use of gender-affirming care to treat it in adolescents and adults.

When I was a teenager, I began to understand that the familiar feeling that crept into my mind throughout childhood was in fact gender dysphoria. I didn’t know what being transgender was when I was a child, so I tried to rationalize my chronic discomfort.

Maybe I just liked wearing boys’ clothes.

Maybe I was just copying my older brother, Sam.

Maybe other girls wished they had been born as boys too.

My two-year-old self picking blueberries on a farm in Michigan. Summer 2003.

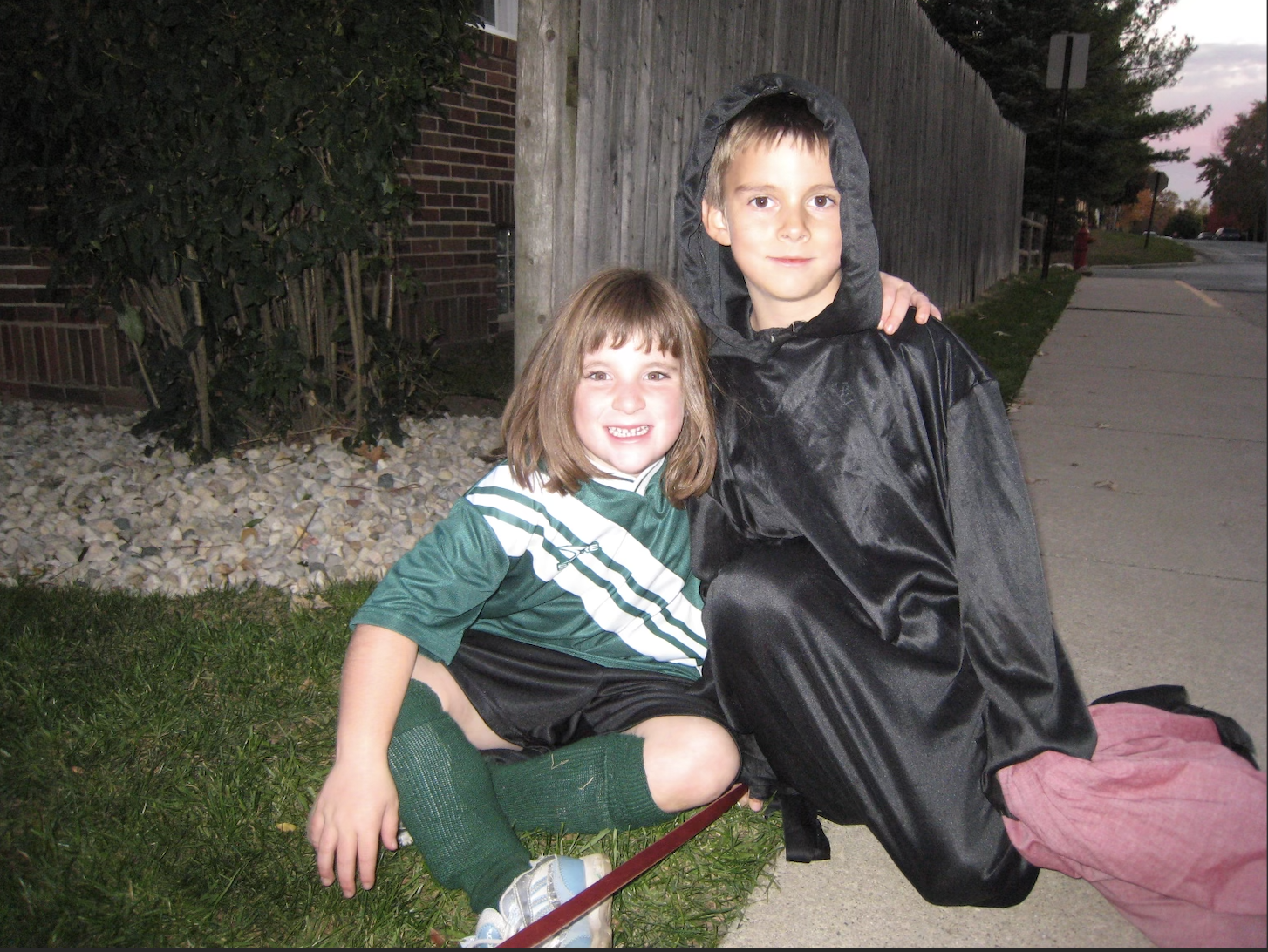

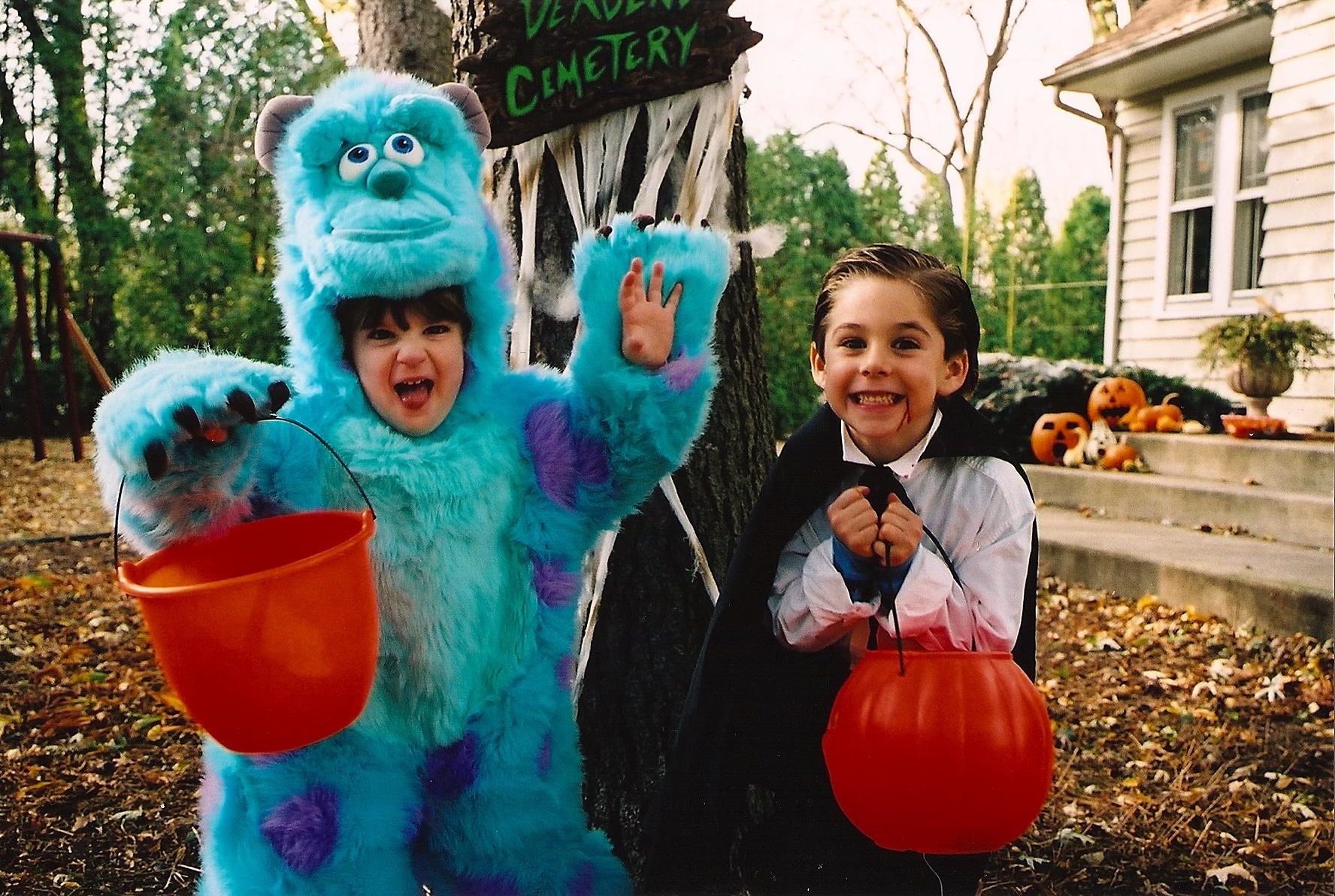

My favorite holiday growing up was Halloween. It was the one day of the year where I had complete autonomy over what was put on my body.

I used my costumes as a vehicle to protect myself. I could hide behind them while trying to understand what it felt like to be comfortable in my own body.

My costumes provided me with a unique sense of liberation that even my soccer jerseys and softball pants couldn’t provide me with. I was free for one day of the year.

My gender dysphoria continued to escalate as I grew up, and the persistence of my distress consumed my entire life by the time I was a senior in high school.

I was certain of three things.

One: I hated my chest because I had gender dysphoria.

Two: I had gender dysphoria because I was a trans man.

Three: I was terrified.

I didn’t want to tell anyone how I felt because I could barely even accept myself. I never wanted to come out and believed that I would keep these certainties to myself for the rest of my life.

My grandmother Judy, older brother Sam and me on Halloween. My mother created my lamb costume from scratch. October 2003.

Emerson Echols was also a child the first time he felt gender dysphoria.

“Before you realize you’re trans or have the language for it, you don’t really know why you’re uncomfortable with certain things,” he said.

Echols, 20, is a trans man who has pursued a medical transition, something he had his mind set on since his sophomore year in high school, he said.

“My dysphoria was always chest-based because that was one thing that, no matter what, was always there,” Echols said.

He had his top surgery in December 2022.

Echols grew up in Taiwan and moved to the U.S. when he was 10 years old. He struggled to wear a skirt everyday as part of his elementary school’s uniform, and he loathed wearing the different dresses required for photos the day he graduated from the school, he said.

The photographers eventually let him choose one outfit.

“I picked this tacky Robinhood costume. They still put lip gloss on me, but I was just so happy to be able to hold this shitty little plastic bow and for once be wearing something that wasn’t a dress,” he said.

Echols and I reminisced about the times we were allowed to wear costumes as children. It’s incredible to me how cheap fabrics and pieces of plastic provided such immense comfort.

I began to seriously consider a medical transition when I was 19, but the only person I told that I was transgender was my best friend, Archie.

We’d been friends since we were in preschool, and he’d always been supportive of my transness when others in my life were not.

I even remember him asking me if I was trans one day when I was 14. I panicked and said no even though the thoughts clouded my mind daily.

My best friend Archie and I on Halloween where I had dressed as a soccer player for the third year in a row. October 2007.

I waited until I was 20 to tell my family that I was trans. I came out on the morning of Thanksgiving and was not met with the support I desired. My mother was particularly disturbed by my announcement, and I was told that I ruined the holiday.

At that point, I accepted the fact that I would never be supported if I pursued a medical transition, but I couldn’t continue to live the way I did.

I couldn’t leave my apartment without having a panic attack because I was scared I was going to be attacked for looking visibly trans.

I couldn’t look at myself in a mirror because I hated how feminine my face looked.

I couldn’t shower with the lights on because I cried whenever I looked down at my body.

I was surviving, not living.

I felt a strong desire to begin hormone replacement therapy to alleviate my gender dysphoria that continued to worsen, but I desperately wanted my mother’s approval first.

Even when her words hurt me, I loved her.

I wanted her to support my decision. I wanted her to be proud of me. I wanted to hear her say, “I’ll love you no matter what.”

It took months of tearful conversations and arguments for me to finally start feeling the support I craved.

She began to listen to me, and she began to learn. As she understood my identity more, our relationship improved. I felt proud of her growth, and I finally felt like she was proud of me.

My mother and I at Wrigley Field for a Cubs game on Mother’s Day. May 2005.

I started taking testosterone the summer after I came out to my family.

I desperately wanted top surgery too, but the process of undergoing the procedure is filled with social, economic and physical barriers.

Every surgeon I reached out to had a waitlist multiple years long.

My insurance wouldn’t provide me with a clear answer of what expenses would be covered.

Cisgender psychiatrists and physicians evaluated me and dictated whether or not I should be allowed to have this procedure.

The process was confusing and frustrating, but I was eventually able to book a consultation with a surgeon I liked and was offered a surgery date for June 2023.

I went through the process of securing and scheduling my top surgery throughout 2022, and I can gladly say that it’s now eight days away.

By the time this story is published, it will have already happened.

Hormone replacement therapy alleviated much of my gender dysphoria and improved my mental health overall, but I’ve eagerly been counting down the days until my surgery since I booked it over a year ago.

I’m ready to finally feel better, and I wish I could tell my childhood self that I would eventually feel better one day.

I wish I could tell him that it’s normal to feel angry when his friends that were born boys could take off their shirts, but he wasn’t allowed to as a child.

I wish I could tell him to ignore the bullies who made fun of him for wearing his brother’s hand-me-down clothes when he was in middle school.

I wish I could tell him that it’s okay to cry when he had to start wearing bras because he was going through the wrong puberty.

I wish I could tell him that he wasn’t mentally ill when he realized he was trans his senior year of high school.

I wish I could tell him that he was brave when he wore a suit to his prom, and some of his classmates stared and laughed at him.

I wish I could tell him that one day he’ll feel strong enough to tell his family that he’s trans, and he won’t have to live the rest of his life hiding.

I wish I could tell him that he’ll be able to start hormone replacement therapy when he turns 21, and his family will support him throughout his transition.

I wish I could tell him that he will persevere and have his top surgery three days after graduating from college.

I wish I could tell him that I understand all those feelings now.

I wish I could tell him that one day he’ll feel like it’s Halloween every day.

My brother and I on Halloween when I wore my favorite costume as Sully from the movie “Monster’s Inc.” October 2005.

Header image by Bridget Killian

NO COMMENT