Federally Funded All-Stations Accessibility Program is 20 Years Too Long

“All I remember is crossing the street, blinking, and when I open my eyes I see a nurse in front of me asking me where I was, what had happened.”

DePaul junior Julian Aparicio experienced a serious brain trauma injury in 2005 after sitting on the top of one of his friend’s cars as a joke, and, as a prank, his friends decided to drive off. Aparicio was in a coma for three weeks. Since the accident, he has been using a wheelchair.

Aparicio returned to school and work, but navigating the city on public transportation with a wheelchair has been more challenging than expected. The main source of his frustration comes from the unpredictability of the elevators.

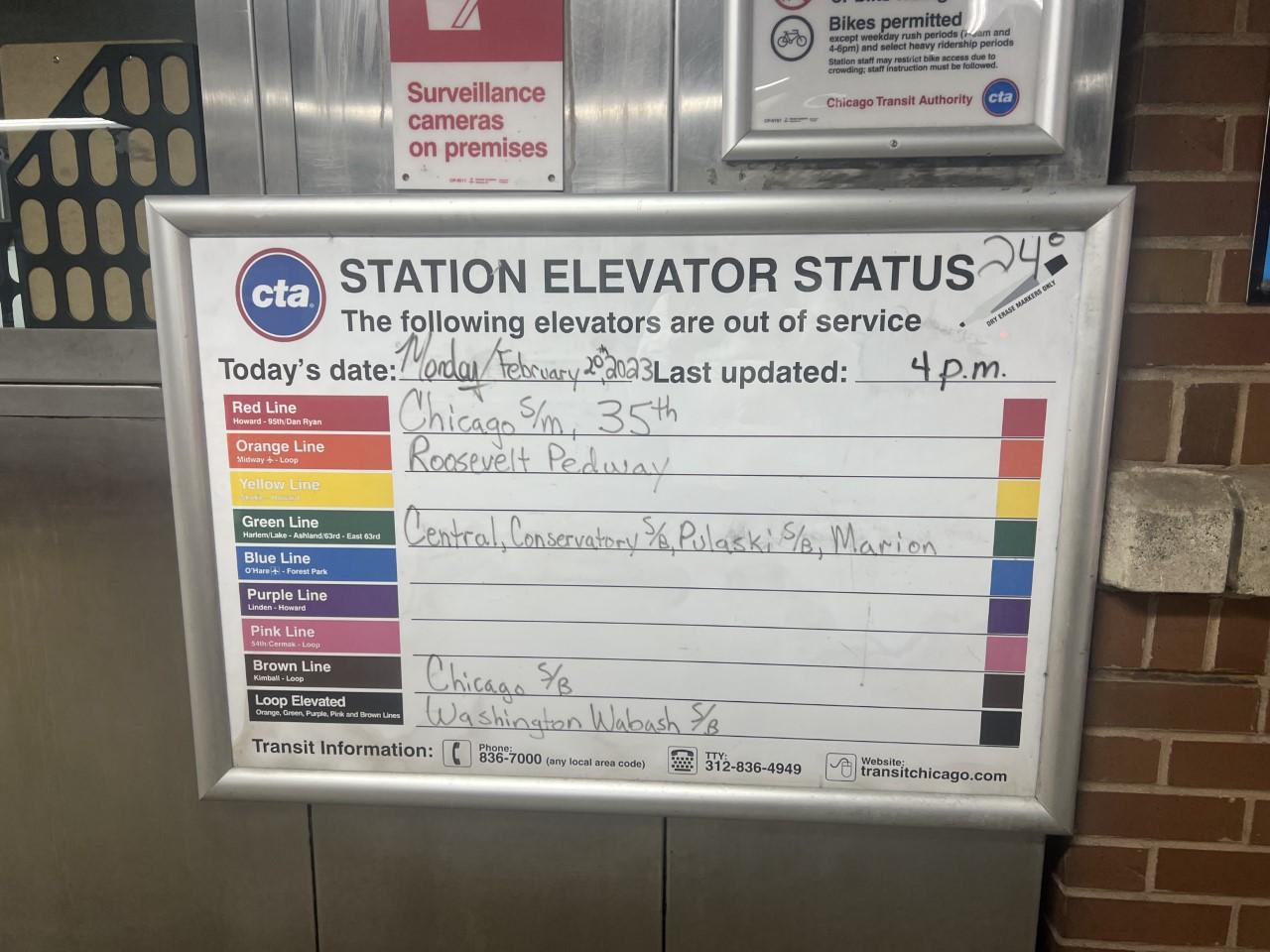

Station Elevator Status at Harold Washington Library Station. Photo by Alexandra Murphy.

“One of the problems that I sometimes face are the elevators are out of order,” Aparicio said. “The sudden malfunctioning of elevators makes it hard.”

Aparicio also struggles with having to re-plan his routes depending on which stations are accessible with working elevators and which ones are not. Additionally, getting a service worker to recognize that Aparicio needs help getting on and off the train also proves to be difficult. To enter the car, Aparicio needs to wait until a CTA employee sets up a ramp on the platform.

Aparicio tends to avoid the Red Line because of CTA workers’ lack of patience, and of the fast-paced atmosphere of the train itself. He often rushes to get onto the platform. Aparicio prefers the Brown Line as his main method of transportation because the CTA staff is more gracious.

“In the past couple of weeks, I haven’t been feeling well, I’ve been really weak,” Aparicio said. “So, I’ve been taking the Brown Line instead of the Red Line because I know with the Brown Line there is more patience.”

All Stations Accessibility Program

Currently, Chicago has 103 of 145 CTA stations in Chicago that are accessible to people living with a disability, leaving 42 rail stations that are inaccessible. Over 520,000 Chicago residents or 10.1% report having a disability, according to the city of Chicago website. Even with the number of stations accessible, many of the promoted accessible features on public transit have issues, including the inconsistency of the elevators, lack of elevated ramps, and overall support to get up to the platforms.

As a result, in 2018, CTA introduced the All-Stations Accessibility Program (ASAP) and later passed it into federal law in July of 2021. The 20-year-long program received $118.5 million in federal funding. According to the City of Chicago website, the program makes all transit stations fully accessible for those who are disabled. However, the four-phase program has not made urgent changes despite the large amount of federal funding given to the city of Chicago.

The Quincy stop is one example of an accessible station that has recently been updated with new elevators and ramps. Photo by Alexandra Murphy.

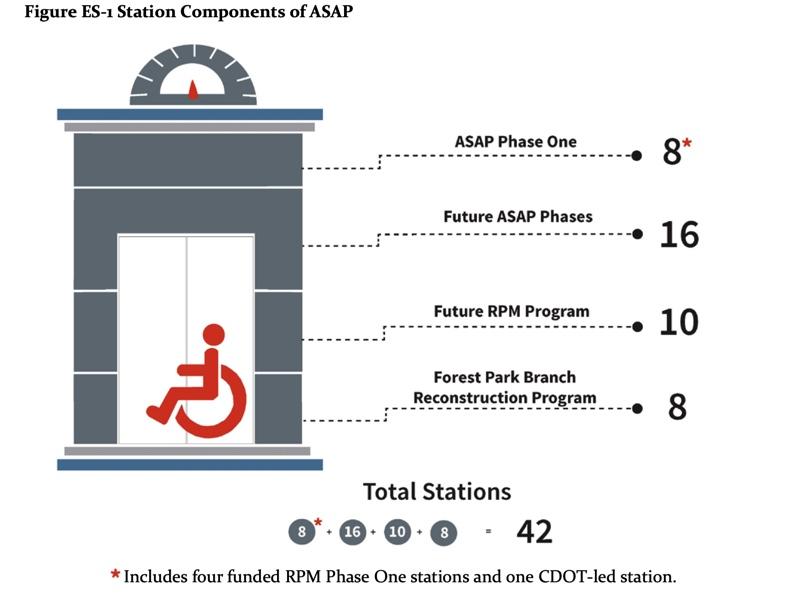

The ASAP program is split into four stages. The Transit Chicago website only laid out in detail phase one. This phase will update eight stations and the following phases will update the remaining 34. The last two phases include the RPM (Red and Purple Modernization) Program and the Forest Park Branch Reconstruction Program, set to happen much later down the line in the 20-year-long ASAP program.

Austin (Green) stations, Montrose (Blue), and California (Blue) lines will be the first accessible stations in Phase 1.

Photo credit: The Chicago Transit website.

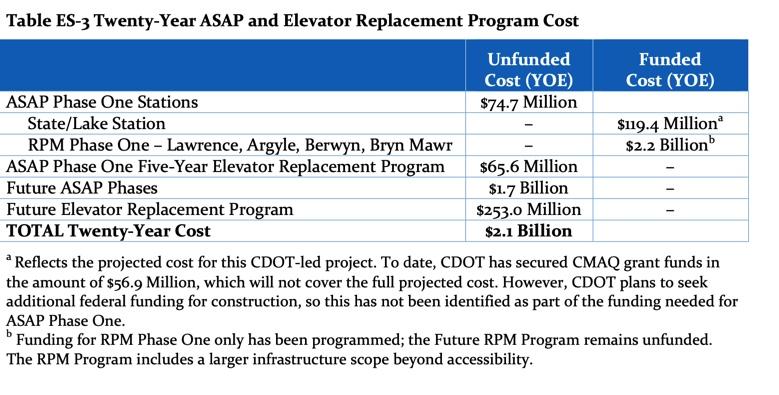

The projected cost of Phase 1 phases in comparison to the future ASAP phases, with the expected cost being $74.7 million. Future phases – that will not be made accessible for a while – have a projected cost of $1.7 billion. For the 20-year program, including the RPM phase cost and Elevator Replacement Program costs, the unfunded amount totals $2.1 billion.

Photo credit: The Chicago Transit website.

All Access Living, a Chicago-based advocacy group for the disabled community, agrees that the 20-year-long program is 20 years too long.

Laura Saltzman, the policy analyst on transportation at All Access Living, agreed that there should be a push for urgency when it comes down to quality of life for disabled riders. “We would of course prefer if the plan to meet the standard was faster,” Saltzman said. “The ADA was passed 30 years ago.”

When asked about some of the improvements that can be made for the stations to be more accessible, Saltzman expressed the need for making even the surrounding area of the sidewalks on each train station more accessible. Especially during winter, traveling in the snow can be a struggle for people with disabilities.

“The city needs to make sure people can get to the train by making sure there are accessible sidewalks everywhere. That means timely sidewalk repair, installing ramps where there are currently no ramps and plowing the sidewalks in the winter so they are not covered with snow or ice,” Saltzman said.

Aparicio also noted the lack of accessibility on the sidewalks for two reasons. One, the sidewalks getting off some of the train lines have a bumpy texture that makes it difficult for any wheelchair to roll smoothly on. Additionally, the snow and ice on the surrounding sidewalks during the winter makes it challenging to arrive at the stations while using a wheelchair. During this time, Aparicio said his only solution is to ask the train conductor for help.

“Sometimes I do my best to get the first train car because then the train conductor can see me,” Aparicio said. “Then, they are aware that I’m on the train.”

Inaccessibility on the CTA for people living with invisible disabilities

Other disabled riders face additional hidden challenges posed by Chicago’s main transportation system.. Autism, an invisible disability, poses many sensory challenges when the elevators are often left unkept, and there are no strict regulations set in place for smoking in train cars.

David Hupp, a DePaul University student and member of the Student Government Association, grew up with autism and experienced many sensory issues, along with chronic fatigue and chronic pain. For Hupp, the CTA failed him with limited train cars available to escape the constant overload of stimulation with any strong fragrances or smoking. He expressed the frustration of getting on the train with the high likelihood of inhaling smoke.

A No-Smoking Sign posted on the Quincy station train platform. Photo by Alexandra Murphy.

“About five years ago, people started smoking regularly on the CTA. This did not used to be a thing. I’ve been riding the CTA for like 20 years, and prior to about five years ago I could have counted on one hand how many times I’d encountered someone smoking on the CTA,” he said.

This is one example of many issues that have come up for individuals who experience sensory issues.

According to a Chicago Tribune article about the Blue Line, the University of Illinois at Chicago’s School performed a 2017 study which found that this is the loudest stretch of the track in the system with “cars growing to a deafening roar” and the “screech of wheels grinding on the tracks.” This makes it near impossible for just about anyone to travel without discomfort, let alone someone who lives with a disability that poses a sensory issue.

Not Only a Chicago Problem

Chicago is one of many cities in the U.S. that has little accessibility for people with disabilities.

New York City has one of the worst accessible public transit systems out of any that exist in the world. The NYC Metra system has been criticized for inaccessibility, and only 126 of the 472 total stations, or 27%, are considered accessible to those with disabilities. As a result, the city recently proposed a change to the Fast Forward Plan, which includes the installation of more elevators in the stations. Fast Forward plans to reach the maximum possible accessibility in 10 years. Even with the 358 stations that are left inaccessible, NYC still has a faster plan in mind to make public transit more accessible for the disabled community.

On the other hand, in other large cities like Seattle and Boston, the public transit systems are already extremely accessible by ADA’s standards.

Other cities can look to Seattle’s successful transportation infrastructure, including a system that has street cars, buses and water taxis to get around. According to the Seattle Department of Transportation, the Seattle streetcar is “accessible and easy to board for all users.” The department also explained there are wheelchair ramps that automatically deploy upon the press of a blue button on the inside or outside of each streetcar.

Boston is the runner-up to Seattle with 98% of their “T” stations accessible for people with disabilities. According to a Washington Post article, the Boston “T” may be accessible for riders, but there have been issues with elevator uptime.

Where Chicago Stands Today

Currently, the All-Stations Accessibility Program is still in Phase One of the 20-year-long project to make all rail stations fully accessible by 2038. Today, the majority of the four phases included in the ASAP program remain unfunded, and the disabled community continues to be directly affected by the lack of accessibility on the CTA.

Header by Mei Harter

NO COMMENT