Shedding Light on Environmental Racism Within Chicago

“We’re so normalized to living in a dumping ground for the city,” Oscar Sanchez, the cofounder of the activism group Southeast Youth Alliance, told the Natural Resources Defense Council.

It is no secret that Chicago has a lot of racial and economic inequality between neighborhoods, as seen through the continued gentrification and the lack of investment in Chicago’s West and South Sides. However, there has been research portraying environmental inequality. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says African American and Hispanic individuals are more likely to be vulnerable to environmental factors, like extreme temperatures.

Professor Rosa Cabrera is the director of the Latino Cultural Center and an adjunct professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Cabrera defines the term “sacrifice zones,” which are areas that have a history of ample industrialization that cause the highest environmental contamination and levels of air pollution.

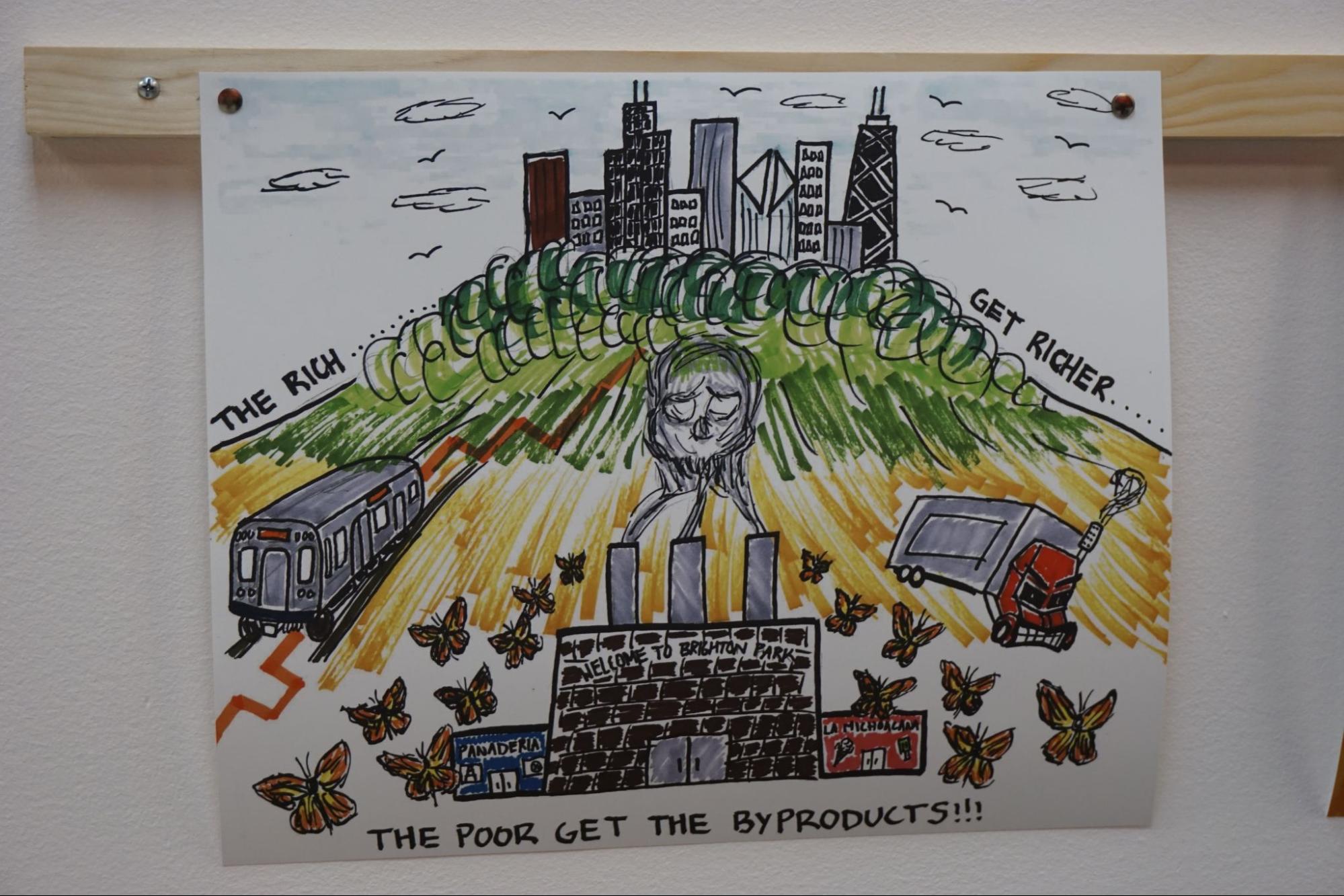

An infographic showing sacrifice zones in Chicago at the Climate’s of Inequality: Stories of Environmental Justice exhibit in the Chicago Justice Gallery. Photo by Gia Clarke.

Cabrera said the sacrifice zones in Chicago are Pilsen, Little Village, McKinley Park, Altgeld Gardens, the Southeast Side and Calumet River. These neighborhoods are in the South and West Sides of Chicago, which are primarily where Black and Latine communities live, Cabrera said.

White people are more concentrated in the North Side, Latine people are more concentrated in the West Side, and Black people are more concentrated in the South Side, according to South Side Weekly’s interactive map.

“There is a very clear correlation between environmental harms in places where people live and race, and that’s why it has been called environmental racism,” Cabrera said.

The term environmental racism was coined by Rev. Benjamin Franklin Chavis Jr., former executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

He defines environmental racism as the “racial discrimination in environmental policy-making, enforcement of regulations and laws, and targeting of communities of color for toxic waste disposal and siting of polluting industries,” according to a speech Chavis Jr. made in 1982.

Environmental racism is seen here in Chicago, especially with where the city chooses to allocate the industrial areas. The North Side, which is predominantly white, has fewer issues with the city wanting to build large factories.

For example, there was a big push to move the General Iron factory from Lincoln Park to the Southeast Side of Chicago. It was only with continued citizen protest and pushback that stopped the move from happening, according to Brett Chase’s report from the Chicago Sun-Times.

This is a problem especially because “those communities [Pilsen and Little Village] are burdened with asthma and other respiratory health problems,” said Jill Hopke, an associate professor specializing in climate communication at DePaul University. Hopke said Pilsen and Little Village are primarily Latine.

Another issue that affects low-income neighborhoods in Chicago is the lack of tree coverage and green space in the South and West Side of Chicago.

Mark Potosnak is a professor in DePaul’s College of Science and Health who specializes in air quality and climate. Potosnak says Chicago has many urban heat islands, which are areas that don’t have a lot of trees or green space.

“Imagine a blacktop… It’s a solid surface, and the color black means you absorb sunlight, so all the heat from the sun goes into absorbing. A tree has the power to be able to suck water through it,” Potosnak said, “By the tree evaporating water, it can cool itself off and the surrounding areas…The urban heat island effect is just that added up over all of Chicago.”

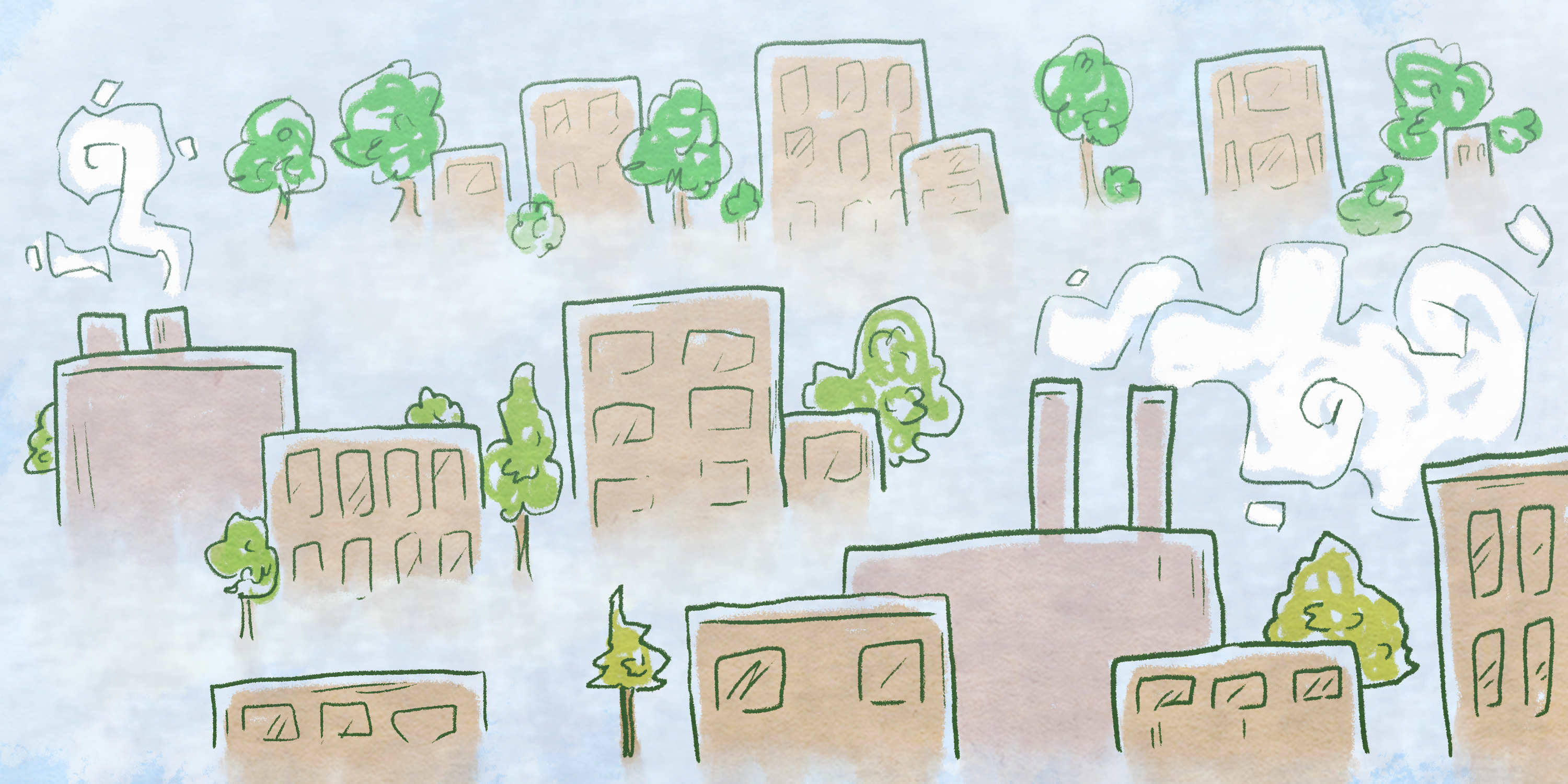

As shown in the graphic above, green space is mostly concentrated in the North Side of Chicago, while the South and West Sides have very limited tree coverage. Potosnak says the reason for this lack of tree coverage is because neighborhoods like Lincoln Park have the means to fund green space, while neighborhoods like Pilsen and the Southeast Side don’t.

“Wherever we walk in Lincoln Park, we see nice trees. A lot of stuff on the South Side, not nearly so many trees,” Potosnak said.

Potosnak also states it’s not enough to simply plant more trees, because in order for those trees to stay alive, neighborhoods need more resources to invest in upkeep and maintenance.

“In under-resourced neighborhoods, they’re under-resourced. They don’t have the social capacity, they don’t have the population density, a lot of factors they don’t have; and the trees die,” said Potosnak.

Even in the limited green spaces under-resourced neighborhoods have, the city will continue to abuse those parks, Cabrera said. Cabrera says Riot Fest is one of the main examples of this. Riot Fest is a yearly music festival held in Douglass Park, which is located in North Lawndale and parts of Pilsen.

Professor Rosa Cabrera at Climate’s of Inequality: Stories of Environmental Justice exhibit in the Chicago Justice Gallery. Photo by Sarah McFeely.

Cabrera says the residents near Douglass Park have been protesting for years to move Riot Fest somewhere else, as the event causes two problems; residents cannot access the park, and festival goers leave a lot of garbage on the ground that doesn’t get picked up often.

“Some people in certain neighborhoods obviously are more valuable than others to the city,” Cabrera said, “[Riot Fest] is one example of the inequities. Inequities in investment that the city puts towards some neighborhoods more than others.”

Drawing from Unnamed Artist at Climates of Inequality: Stories of Environmental Justice exhibit in the Chicago Justice Gallery. Photo by Sarah McFeely.

Header by Julia Hester

NO COMMENT