The Chicago Covenants Project is working toward identifying all racial covenants in Chicago and Cook County

In the basement of Chicago City Hall, there are thousands upon thousands of pages of housing contracts for all of Cook County. Contained in white books that are 12 inches by 18 inches, the books sit on brown, wooden shelves, waiting to be inspected by volunteers and researchers from the Chicago Covenants Project. Photography is not allowed in the records room.

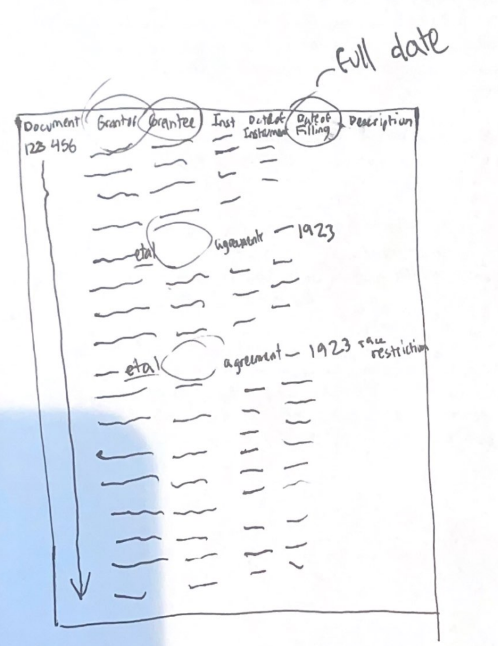

Example drawing of a page from the record books. Drawn by Lauren Sheperd.

Each book is labeled with the city and the book number. There are typically around 400 pages per book of contract records, though the number of filled pages varies book by book.

There were 12 volunteers in the basement on October 6, all of whom were given a book and a piece of paper to record each racial covenant they found. The goal for the volunteers is simple: identify every racial covenant in Cook County.

Covenants as a whole are not the problem – those are just agreements between two or more parties put on land that tell property owners what they can and cannot do with it. Covenants become an issue when they include language and intentions that are considered racial. “A racial covenant – also known as restrictive covenants – are agreements put in place, both by developers and by neighbors,” said Chicago Covenants Research Coordinator Maura Fennelly.

These covenants were created in the late-19th and early- to mid-20th centuries, and “specifically prohibited specific groups of people from residing in certain areas,” Fennelly said. In Chicago, those restricted were mainly of the Black community.

The project began in the Spring of 2021, and since then, researchers and volunteers have gone through about 20% of all real-estate index books covering the City of Chicago. So far, they have located approximately 1,000 covenants covering 100,000 parcels or plots of land.

Specifically, they have finished looking through all parcels in Hyde Park, Beverly and Greater Englewood and are partially through research on Back of the Yards, Kenwood, Woodlawn and Park Manor. The Chicago Covenants Project is just starting their research into Evanston, Rogers Park and Roseland.

There is a detailed map of the covenants that have been found on the project’s website.

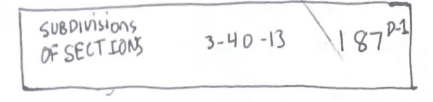

Hand-drawn example of the spine of one of the records books kept in the City Hall basement. Drawn by Lauren Sheperd.

What do racial covenants look like?

Upon arrival, volunteers were given instructions by Fennelly. The instructions are to help volunteers identify each racial covenant in the book they were given.

There are a couple of indicators within the contracts that are important for volunteers to look out for. The first is a blank space under the grantee – the recipient of a property – section of the contract. This indicator stands out most to volunteers who are just scanning the page because there is a blank space where the name should be.

The next indicator of a racial covenant is found in the grantor – or the seller of the property – section. Typically, this section will include just one or two names. However, if the contract is a racial covenant, it will include a name and then “et al.” This means that multiple people – usually from the same block or neighborhood – signed onto the covenant to keep those of “undesirable” racial and ethnic groups out of their areas.

According to Euan Hague, the director of DePaul’s School of Public Service, those restricted in Chicago were typically Black or Jewish. Hague is also affiliated with the geography department, and his studies focus on urban planning, development and policy.

“What would normally happen was that you’d have a threshold – let’s say, 95% of the property owners on the block – had to sign and agree to it,” Hague said. “If they finally agreed to it, then that was now considered a law.”

Other indicators that a contract is a racial covenant are the instrument of the contract and the date the contract was filled.

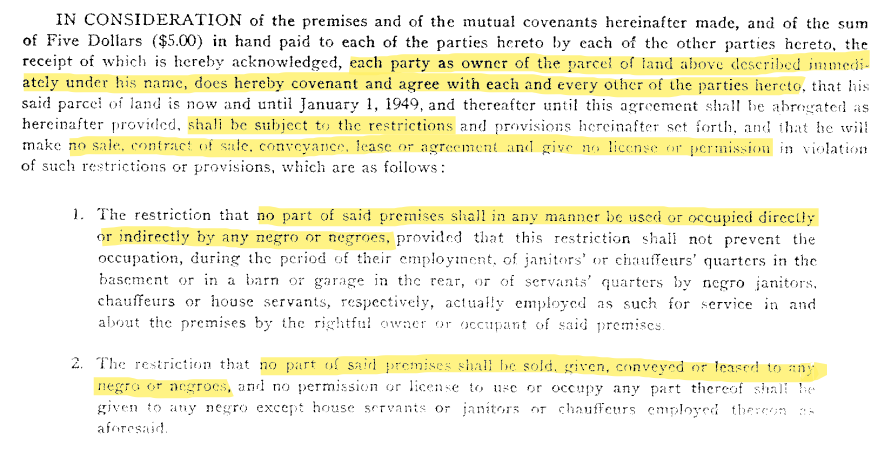

Excerpt from a covenant contract. Provided by Maura Fennelly.

The instrument is the type of contract that was filed. In the case of a racial covenant, the instrument will be an agreement for deed – signified by the letters (AGRT/D). According to an abbreviation sheet given out to volunteers, an agreement for deed is “an agreement between the owner (seller) and the purchaser (buyer) concerning a parcel of real estate.”

The date of filling is also key when identifying a racial covenant. According to Fennelly, volunteers are supposed to look for filling dates between 1880 and 1950.

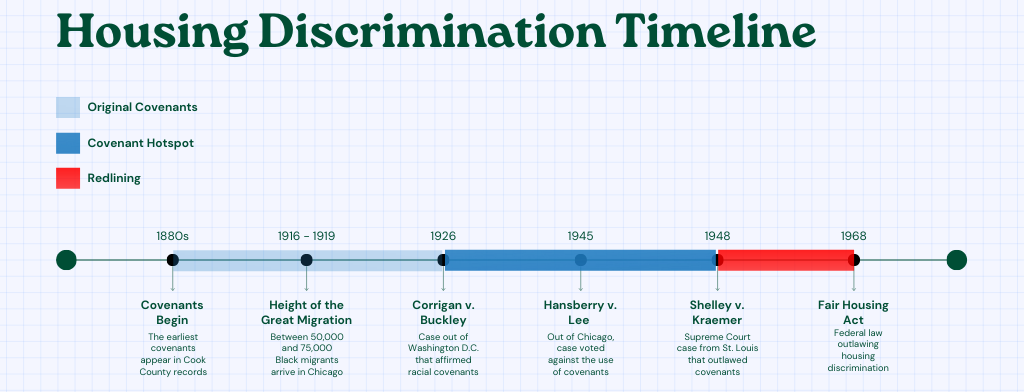

“There’s a really important Supreme Court case that you may or may not be familiar with – Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) – that happened in 1948 that deemed that covenants were unconstitutionally enforced,” Fennelly said.

The handwriting on the contracts can often be hard to read, which is why Fennelly suggests volunteers look for 1950 instead of 1948.

Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) was a Supreme Court case out of Missouri decided in 1948. In St. Louis, a Black family – the Shelleys – moved into a neighborhood where a racially racial covenant had been put in place in 1911. A resident of the neighborhood – Louis Kraemer – brought a lawsuit against the Shelleys to enforce the covenant. The Missouri Supreme Court ended up enforcing the covenant in 1945. However, the case was eventually brought in front of the United States Supreme Court three years later, when they decided in favor of the Shelleys. This set the precedent that banned the use of racially racial covenants in the United States.

The final and most clear indicator of a racial covenant is found to the far right of the page in the description. If the covenant is racial the description will directly read “race restriction,” or something similar.

After identifying these contracts, volunteers write down the document number. Fennelly and other researchers then go to the Cook County online database to find the full contract to study and publish on their website. Though the project is not even close to done, the Chicago Covenants Project has estimated that 80% of Chicago’s homes were covered by racial covenants.

Timeline by Lauren Sheperd.

The History of Housing Discrimination: Where Do Covenants Fit In?

Racial covenants are just a small part of a long history of housing discrimination and segregation.

A rough start for when housing discrimination began in the city is the 1880s – which, according to Fennelly, is when racial covenants begin to be seen in public record. This follows patterns of migration of recently freed Black Americans fleeing the South to northern cities such as Chicago following the collapse of Reconstruction.

According to an article written by James Grossman, a researcher at Northern Illinois University, nearly 25,000 Black “Exodusters” began to move west to Kansas. This movement began what is now historically referred to as the Great Migration.

Though racial covenants began to pop up in records in the 1880s, they became far more common in the 1920s, according to Hague, when the Great Migration really picked up speed. According to Grossman’s article, “approximately 500,000 Black southerners between 1916 and 1919” moved north. Between 50,000 and 75,000 of these migrants came to Chicago.

Also before the 1920s, housing discrimination was built directly into a city’s zoning laws. However, this changed after the 1926 Corrigan v. Buckley Supreme Court case. “Although some of them [covenants] predate the 1920s, the real boom was the 1920s and ‘30s, which is really the kind of peak period of use of this type of legislation,” Hague said.

Corrigan v. Buckley (1926) upheld the constitutionality of racial covenants in the United States. The case came about when a Black family bought a home in the Dupont Circle area of Washington, D.C. – violating the racial covenant that was in place. Just one year prior to the Curtis family purchasing the home, white residents signed a covenant that read that no property was to be sold or rented to “persons of the negro race or blood.” The case was brought in front of the D.C. Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the covenant. The NAACP had taken on the case and tried to push it to the United States Supreme Court. However, they declined to hear the case because covenants were contracts between individuals.

Before the Supreme Court banned racial covenants in Shelley vs. Kraemer (1948), covenants popped up all across the city of Chicago and Cook County. During this time, the Black Belt of Chicago formed in what is now Bronzeville down Indiana Avenue.

“You’ve got more and more people living in the same amount of space, which obviously leads to deterioration of property conditions, and deterioration of housing,” Hague said. Even though wealthier Black residents wanted to move out of this area, they were unable to due to racial covenants across the city, especially in neighborhoods such as Hyde Park and Englewood.

This led middle class Black Chicagoans to fight against these covenants. Hansberry v. Lee (1940), which came directly out of Chicago, was one of the first wins for a Black resident fighting against the covenants. While no legislative changes were made until eight years later, Hansberry v. Lee (1940) helped expedite the fight against racial covenants.

Hansberry v. Lee (1940) directly challenged covenants in Chicago. According to Hague, the case came up when Hansberry, a Black man, attempted to buy a house in the Hyde Park area, where a racial covenant had been signed. While the majority of property owners in the area agreed to and signed this covenant, the requirement of 95% of property owners was not met. Based on this issue, the court ruled in favor of Hansberry. While this case did not outlaw the use of racial covenants, it did assist greatly in the movement to get them legally banned.

Even after covenants were made illegal, housing discrimination in Chicago and across the United States persisted. “Once covenants become no longer legally enforceable, after 1948, you begin to see what is called blockbusting,” Hague said. “This is the beginning of white flight as well.”

Blockbusting was perpetuated by real-estate agents looking to make money, according to Hague. As soon as one Black family would move into a certain neighborhood or onto a certain block, real-estate agents would tell the white residents that their area was on the decline and convince them to sell for much less than their property was actually worth. White families often ended up moving out to the suburbs after this.

However, real-estate agents would not sell the properties they collected. Instead, they would rent them at high prices to Black families who – because of mortgage discrimination – were often unable to become homeowners.

While Black families were moving out of the Bronzeville area at the time, they stayed relatively close, creating Chicago’s predominantly Black South Side.

Modern-Day Implications

Chicago was named the most segregated city in the United States in June, according to Brown University data. This is not a new trend, and Chicago has been ranking either first or high up on the list for decades. Brown used three measures to analyze housing segregation in American cities: dissimilarity, exposure and isolation.

According to a WBEZ analysis of this data, Chicago’s 2020 dissimilarity index is at 80.04%. The dissimilarity index is defined as “a measurement of the percentage of either group, in a given pair, that would have to move in order for the two groups to be evenly distributed in any given area.”

“Racial covenants are one of the ways in which the current patterns of segregated racial segregation in Chicago were set,” Hague said.

Because the Black population had been restricted to such a specific part of the city, they built up communities in this area. Even when they were able to move after the banning of racial covenants, many stayed close to where they or their families originally settled. “Typically, you move to the next neighborhood over because you want to go to the same school, you want to keep going to the same church,” Hague said.

According to Fennelly, racial covenants also have led to the extreme racial wealth gap we see in Chicago and the rest of the United States. According to data compiled and explained by Prosperity Now, the median household income for Black Chicagoans is $30,303 a year. For white Chicagoans, the median household income is $70,960 per year.

This pattern translates to home ownership, as well. While 54% of white households own their homes, only one-third of Black households do.

The cause of this gap has to do not just with present-day disinvestment, but also historical factors including the racial covenants.

According to Hague, because Black Chicagoans were unable to buy a home, they would just continue to rent in the Black Belt of the city. Black Chicagoans “would not have been able to build up the generational wealth in that property,” and would not have been able to eventually pass that property down to their children and grandchildren.

“That’s really where some of these issues really kind of resonate today,” Hague said. “One of the things that obviously is important to somebody’s finances is inherited money.”

One of the easiest and most common ways to build familial investments and wealth was through real-estate transactions kept within the family. “What restrictive covenants did was deny that entry point for many African Americans, really until the 1950s,” Hague said.

So, What Now?

Fennelly and her team of research assistants have been hard at work, and they aren’t even a third of the way through the record books.

“The main goal is to identify where every racial covenant is in Cook County,” Fennelly said.

She added that it is also important that her team documents the extent of racial covenants. They want to document how “profound and expansive it was.”

Hague also stressed the importance of locating every covenant contract. Because of how housing records and contracts are created, those that had racial covenants decades ago still contain that language today. “In the racial covenants, it would also say ‘cannot be sold to a member of the Negro race’ or something like that,” Hague said.

Projects across the country – include the Chicago Covenants Project – have been working to find and eliminate this language. “There’s been efforts to basically find and there’s probably what some part of the project here is to kind of find that, and then raise it and then highlight it, and then make sure future contracts don’t contain that language,” Hague said.

Fennelly and other researchers are also hoping that their work will help to spur the movement for racial financial reparations. According to the Movement for Black Lives, reparations are “ the act or process of making amends for a wrong.” When it comes to reparations for housing discrimination, they will typically be financial.

“This project also supports the need for more reparations in terms especially as it relates to housing discrimination,” Fennelly said. “Across the US, it was people of various different groups, prohibited from owning homes within quality housing and things like that. Whereas many, many, many white people were able to do so.”

Fennelly hopes that as the Chicago Covenants Project continues to progress, their work will be further recognized and assist in making Chicago a more equitable city.

The Chicago Covenants Project is always looking for more volunteers. More details can be found here.

Header by Ally Ohr

NO COMMENT