The power of images in telling the story of a genocide

Editor’s Notes: This story includes descriptions and visual representations of war and genocide.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 14 East.

“Photographs have replaced the stories of our ancestors. It’s enough to see their faces. We don’t really need to know their stories, the details of their lives. It’s enough to see them, as if they’re living, to look into their eyes, to see a person. We are there with them, yet not.” writes American writer Susan Sontag, in her collection of essays, On Photography.

Man-Made Horrors

In the aftermath of World War II, images demonstrated their power to disturb. Photos of people and spaces in recently liberated concentration camps and ghettos throughout Europe detailed the grim reality of the Holocaust and exposed the barbarity of the further atrocities in which Nazis engaged. Similarly, the image of the mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki further illustrated the depths of human depravity and the willingness to commit mass murder. When a viewer feels something through images of another’s destruction, they’re reminded of their first, and most important, allegiance, that to the world.

Destruction of a housing block (Vernichtung eines Häuserblocks) during Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Photo by unknown photographer.

In her essay “Regarding the Pain of Others,” Sontag examines the multiple responses to images of horrors. She writes that,

“As objects of contemplation, images of the atrocious can answer to several different needs. To steel oneself against weakness. To make oneself more numb. To acknowledge the existence of the incorrigible.”

From this, one can turn to the narratives of the atrocious before the time of photographs. Photography was in its infancy as the United States committed heinous acts of genocide against native populations who inhabited the lands before them. Without easy-to-use cameras, it was difficult to capture the horrors perpetuated by the US government. When photography emerged, it was almost too late. Photographers like Edward Curtis had to travel far West to capture a lifestyle that was long removed from its origin, to see the effects of crimes that had already been committed.

Because of this absence in our visual language, students can only learn of these events from reproductions and stories. As they are interpretations, reproductions lie. They cannot capture the abject horror of reality. The emotions may affect us. They may cause us to shy away from the truth, but we can’t see the people, only recreations by people. With spoken stories, listeners can only hear events as passed down by generations and distanced from the experiences that they relay.

These are the stories that remain. While they need to be valued, documented, and seared into our memories, written and spoken languages are a one-dimensional tool—they can only do so much. As each generation of Americans grows more removed from that which happened before we lose ourselves to complacency, to an aching regret.

On December 29, 1890, the US military executed the Wounded Knee Massacre, killing around 300 Lakota men, women, and children at the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. This massacre remains the largest mass shooting in American History. For qualities such as “gallantry” and “bravery” at Wounded Knee, 20 U.S. soldiers received the Medal of Honor, America’s highest military decoration.

The camera was present to capture the aftermath of that event. It ensured that history will always document that horrific day. The blood and tears have washed away, and the American history books have forgotten the truth of this struggle. Instead, we must reckon with the few photographs that remain of this settler colonial violence. These photos tell the stories of a specific history of the United States, even if it is one that is fading rapidly.

Three weeks after the Wounded Knee massacre, with several bodies partially wrapped in blankets. Photo credited to George Trager and Frederick Kuhn.

English cultural thinker John Berger, in his essay Uses for Photography, writes,

“The faculty of memory led men everywhere to ask whether, just as themselves could preserve certain events from oblivion, there might not be other eyes noting and recording otherwise unwitnessed events. Such eyes they accredited to their ancestors, to spirits, to gods or to their single deity. What was seen by this supernatural eye was inseparably linked with the principle of justice. It was possible to escape the justice of men, but not this higher justice from which nothing or little could be hidden.”

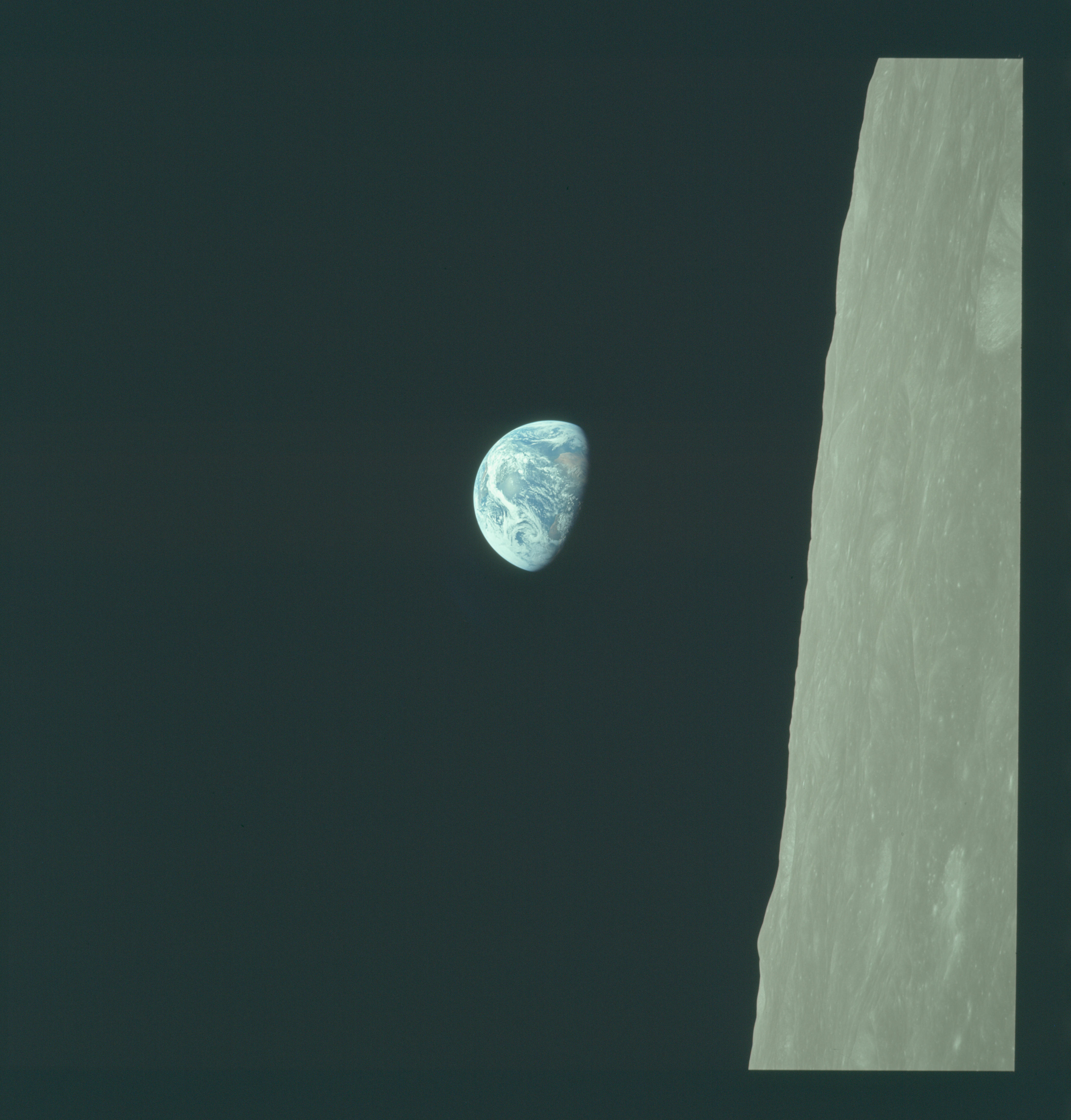

Earthrise

As the crew of Apollo 8 rounded the Moon on Christmas Eve, 1968, and saw the Earth rising out of the lunar horizon, they captured an image that no one had ever witnessed before. Orbital missions had captured the curvature of the Earth and satellites took distant, low-quality pictures, but this was unlike any other.

On the fourth lunar orbit, commander Frank Borman executed a roll maneuver, rotating the spacecraft 180 degrees. As the Command Module turned fully around, astronaut Bill Anders noticed the small, blue Earth, rising in the window. He rushed to get his camera ready. Raising his modified Hasselblad 500 EL, he captured Earthrise, both in black and white and in color.

When a viewer encounters an image, like reading a sentence in a novel, they create the story for themselves. In a book, one sentence will follow another, but with photographs, the story continues long after it’s put down. Graphic images bring intense pain because there is no choice but to feel what they recognize through the violated. Likewise, photos of joy or happiness can generate those same feelings as seen in the image. One can sympathize, empathize, and understand so much of what they see through a photo because they interpret the visual language themselves.

NASA understood the importance those images would have on humanity when they contracted Hasselblad and Kodak to make cameras and film to take to the moon. These were scientists, but they were also explorers, seeing a new universe, one they had an obligation to show to the world. The image and camera build had to be of the highest quality, so when astronauts captured what they saw, they left little to the imagination.

“They should have sent poets and not astronauts, because we couldn’t capture the grandeur of what we had seen” – Astronaut Frank Borman, Commander of Apollo 8

AS08-14-2383 (21713574299), the original photo from which Earthrise was cropped. Photo by NASA/Bill Anders.

At its core, that photo taken more than 230,000 miles away represents humanity at its best, which is why it’s crucial to contrast it with the photos of humanity at its worst. They need to be seen in conversation with each other, and give context to what the other really means. For Earthrise, we understand that despite the faults of humanity, its disputes are inconsequential compared to what it’s capable of. For the rest, despite the advancement of our species, for all the grand steps taken, humans are faulted creatures, stuck with the evils we’ve committed.

All of these images come back to Anders’ Earthrise, the glorious and the god-awful. Images of the extraordinary and the atrocious need to be preserved in the records of human history because they show that humans will live and die with the choices made here on this planet—all of them.

Humans had stepped out into bleak nothingness and had turned around to see the Earth in its entirety, so small, so far away. Plastered across newsstands globally, Earthrise revealed for the first time a completely new perspective to humanity and offered a sense of what it was and where it had gone. The photo is one of the most stunning images of all time. It is a testament to the stunning power imbued in those images, as well as that blue planet standing so quietly alone in the harsh darkness of space.

The Weight of the World

American police murders of innocent people are not a new phenomenon. But now, with an incredibly powerful camera in everyone’s pocket, we see it so much more often. The democratization of the camera helped us see more of the world, its good, but especially its bad. One doesn’t need to be an expert in photography to capture an injustice, or a tragedy, or a genocide. The only task is to aim and shoot.

View this post on Instagram

While the images of horror emanate from around the globe, people forget the names of the photojournalists who took them. It takes courage to point a camera at injustice, and those who do it so often go unknown. Such is the nature of photography—unless investigated further, the author isn’t exposed. Especially in the case of war, the trauma of an image is enough to hide the fact that the observer looks through another’s lens. Photographs aren’t paintings. They’re documented moments of reality. Photographers don’t sign their work. Rather, they speak through their photos. The signature of their gaze is enough. In the crystal-clear images shot in the depths of destruction, we share in terrible moments from all angles and focal lengths. But, the terror shines through, all the same, haunting the viewer and the photographer.

View this post on Instagram

Survival is one thing, but the ability to capture the evil as it occurs takes immeasurable courage. For example, brave Palestinian photojournalists document the violence their communities suffer, even while their homes are razed. Why? Because it’s their job. It’s what’s needed. They do this also because, without their documentation, the world wouldn’t see a crater where a hospital once was or the lifeless body of a child where there was once a smiling face. There are few things more honorable than stepping into an active war zone armed with nothing but a camera. It’s the most important job there is in a war. How will history look back on this plight, on this struggle for life? They are the ones who give us the answer, who will tell the story in spite of their oppressors. They are the ones who tell their truths to history.

View this post on Instagram

In 1993, Kevin Carter took one of the most iconic photos of all time, Starving Child and Vulture, depicting the famine-ravaged Sudan. On July 27th, 1994, four months after the South African photojournalist won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo, he committed suicide. He left us with the words; “I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain … of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, or killer executioners”

A Knife’s Edge

Images of violence will forever exist in the archives of human history, but archives are passive collections. The viewer must go out and contend with history. The question that remains is: how do we deal with the photos to come?

The instant these images are revealed, they place the viewer on a knife’s edge. If they fall to either side, they will land inevitably on to the side of the uninitiated or the side of the fanatic. You can choose to care, entrenching yourself in what you believe. Or you choose to move from one echo chamber to the next. Neutrality does not exist — the act of avoidance is taken the instant a viewer scrolls away.

Social media has made it so easy to move past the uncomfortable. The act of turning away has become habitual. We see enough to know the story, and as we run away from it, we’re slightly relieved that we can move on with our lives. The user glides easily through these images, uninitiated. To slow down and pay attention to just one requires monumental effort. To hold an image in our consciousness for longer than an instant can feel like a strain. But the exertion is not a function of the saturation of our world with images. It is rather a cost of the saturation of our world with the news.

The more often these images emerge in our daily lives, the more the stories portrayed in them grow mythologized in the sphere of cultural consciousness. The people in any image become ghosts as they transform into a symbol of a greater issue. Why has Israel cut off internet access to Gaza? For the same reason Derek Chauvin and his accomplices were so publicly indicted in the killing of George Floyd. Because witnessing a genocide has never been easier. These images of genocidal violence trigger reactions — governments don’t want you to see the mangled, unidentifiable bodies that can so capably indict them.

Whether or not an intended outcome, the State of Israel has guaranteed that the photographs of their action against Palestinians will mythologize them. It will be forever intertwined with the people of Palestine, just as the US with the Native Americans they systematically dehumanized, displaced, and murdered. When all the images have been compiled, the people in these photos will become fossilized as remnants of a past. The names blend together as the cause becomes more potent. It crystallizes a problem viewers can either identify with or ignore. For some, these images will convert them like a religion. For others, they will remain a forgotten memory.

As we interact with images of the ongoing genocide, we need to be aware of our position on this edge. We must also be cognizant that we will inevitably fall one way or the other. Avoidance isn’t a sin. All of us fall on that side at more points than many of us would care to admit. There is no way to hold all of this inside of us. But, we do this from the safety of our warm homes, comforted by a world undisturbed by the horrors of war and genocide. We mustn’t misconstrue the balance between preserving sanity and the cost of complacency. We can turn away all we want, but children are being bombed and unarmed civilians are being brutally killed right now—if Israel reduces a school to rubble, and no one wants to look at it, did it happen? If they have already killed 10,000 and not enough people care, who’s going to stop them from killing so many more?

Earthrise. Photo by NASA/Bill Anders.

The header image is a public domain photo by NASA/Bill Anders.

NO COMMENT