How the presence of Honduran identity has morphed and expanded in Chicago across decades

Nearly 60 years ago, my abuelo arrived in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood, where an apartment attic would become his new home. A few months later, my abuela and tio would accompany him in the vast, unfamiliar territory of America.

My abuelo knew at an early age that he’d immigrate to the United States for the “better life” that many immigrants seek. Through family connections, he obtained residency here after a rough transition from his homeland, Honduras. Learning English took him six months of night classes while caring for his wife and son, who both only spoke Spanish at the time.

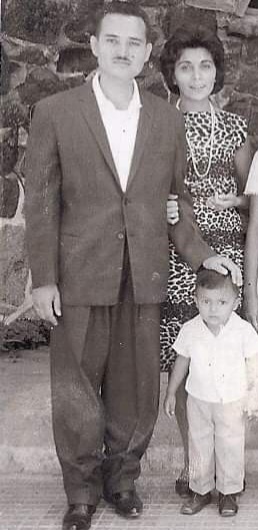

My abuelo, abuela, and uncle in Honduras circa 1963. Photo courtesy of Arnold Diaz.

Although my abuelo was an immigrant, he built one of the strongest Honduran communities in Chicago. In 1975, he founded the Honduran Society of Chicago, which sought to unify the small population of Hondurans in the city through cultural festivities and philanthropic work, specifically during Hurricane Mitch in the ‘80s.

His charisma and passion for maintaining his Honduran roots in Chicago would sadly not live to see many changes, as he passed away the year before the turn of the century in 1999. Nevertheless, our people still establish their strong presence here in the city today.

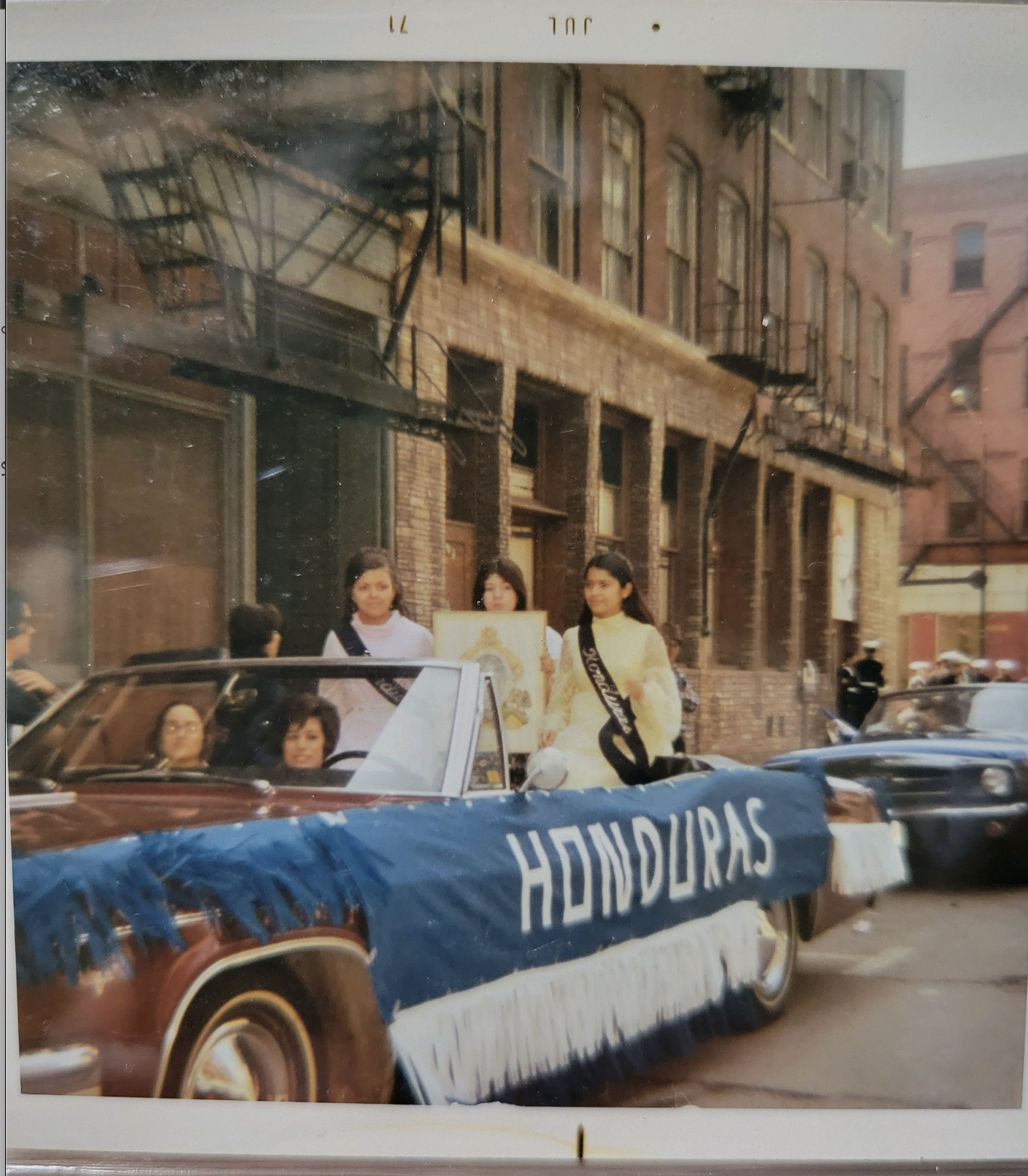

Members of the Honduran Society of Chicago. Photo courtesy of Arnold Diaz.

One of his most cherished family friends, Amalia Guzman, still lives to recount the decades of history and life she’s lived here in Chicago. I smell Honduran tamales every time my dad comes back from visiting her and her daughter, whom he considers a little sister.

“I arrived in Chicago in October 1970, when the cold season began,” said Guzman. “I came with my daughter and husband, and I was eight months pregnant with $30 in my bag.”

As is for many Central Americans, adjusting to the frigid temperatures of cities can be one of the most difficult challenges of immigrating, especially in the heart of winter. Many immigrants in Chicago are currently preparing for the icy winter ahead. Finding a community with a similar ethnic background can be even more of a challenge in this isolated season, as the need for secure housing, food and income overshadows the time to find companionship.

Guzman recalls many financial and emotional hardships shared with her husband Wilfredo when they first arrived in the winter.

“We slept in a twin bed, Wilfredo half his body in the air,” she said. “They were very difficult times, and we felt lost and very sad for having left our land.”

Fortunately, she was able to find a place for her Honduran roots to thrive in Chicago when she befriended my Abuelos.

“It was a friendship that lasted a lifetime,” Guzman said. “Your grandfather was incredibly special, and we used to go to parties in the Honduran Society.”

Since those nostalgic gatherings in the ‘70s, the landscape of Honduran Chicagoans has gone through many cultural changes, yet the community remains strong.

Restaurant owner Carlos Romero sat with us and recalled the intense journey to opening up the place. He fled from Honduras to Chicago eight years ago after his mother pursued political asylum residency.

As a Honduran-American myself, I always felt lost when navigating my Latina identity, often finding myself the only one with an inadequate level of Spanish skills or the only Honduran in a flora of Mexican, Dominican, Puerto Rican and Cuban communities in Chicago. I always yearned to find a rich presence of other Hondurans here in the city.

I was ecstatic when I heard of a new Honduran restaurant opening up in Chicago. I had never tried Honduran food except for inside my home or the country itself. There aren’t many Honduran restaurants around here, so of course, I had to take a trip down there and speak with the owner.

Opening earlier this year, Delicias del Catrachito, which roughly translates to “Pleasures from the Catrachito,” is a humble and cozy place to indulge in the best Honduran dishes. The menu serves an array of items such as pollo frito (fried chicken), platanos (plantains), classic mondongo and seafood soups, and my personal favorite — semitas (a type of sweet bread).

I brought my Honduran cousin to eat with me, as she has missed her homeland food since enrolling as a freshman at DePaul University, miles away from her home in San Pedro Sula. We both enjoyed hefty plates of pupusas and pollo frito, finishing the night with warm pan de coco (coconut bread).

Bright blue walls ornamented with traditional Mayan wood carvings and hand-painted suns complemented a large Honduran flag pinned against one corner. Hundreds of tiny names in Sharpies also scattered the walls, tracking every customer who has eaten at the restaurant. My cousin and I had the pleasure of adding ours, too.

Restaurant owner Carlos Romero sat with us and recalled the intense journey to opening up the place. He fled from Honduras to Chicago eight years ago after his mother pursued political asylum residency. Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador compose what is known as Central America’s “Northern Triangle,” a trio of countries facing immense government corruption and violence, prompting over two million people to flee since 2019.

Carlos Romero and Delicias del Catrachito Crew. Photo courtesy of Carlos Romero.

Unlike my abuelo’s journey, Romero hurdled many more obstacles before landing here in the heart of Kimball. After his father passed away, Romero recounted the feeling of losing everything and the panic which led his family to search for a better life in America. Through all the dangerous situations he faced, his determination never faltered.

“It’s been a long trip,” said Romero in Spanish. “I was kidnapped in Mexico, and then after that, I crossed a river. The immigration [officers] caught me, and I was two months imprisoned. My mom was here [in Chicago], and she had an excellent lawyer who paid the bail. That’s how I was able to get released.”

Despite his entry into America, Romero still had many challenges to overcome in America such as cultural adjustments and the search for a stable income.

“You look for the American dream,” Romero said. “Which then converts into the American nightmare. That course that a human being can go through is the worst. There, you confront your worst fears.”

What began as survival at home blossomed into a pollo frito business inside Romero’s Chicago apartment, where he made around $1,000 a week selling chicken to neighborhood customers.

The “American nightmare” Romero refers to is the antithesis of the “American dream,” what most people associate with suburbia and white picket fences. It promotes the idea that the United States is a place where upward mobility and economic success are equally achievable for everybody regardless of race or birth country, though this privileged mindset is not true, especially for immigrants of color.

Many Black and Hispanic immigrants thus seek this false American dream of easy economic stability and better working opportunities when settling in the United States, but experience generational poverty, workplace racism, higher unemployment rates, healthcare barriers, citizenship barriers and fears of being deported. Upward mobility is an immense challenge for people of color born outside of the U.S., and many times, it is not possible. Learning a new language, adopting Western traditions, accepting low wages and worrying about basic needs are many of the aspects of the American nightmare.

Fortunately, Romero triumphed over his American nightmare and now releases his passion for cooking everyday. Cooking has been a passion of his since he was a child and his father loved his seasonings so much that he said Romero cooked better than his mother.

“I started cooking when I was eight,” Romero said. “When my mom got sick, someone had to cook… my dad loved the flavors of my cooking… so I continued cooking.”

What began as survival at home blossomed into a pollo frito business inside Romero’s Chicago apartment, where he made around $1,000 a week selling chicken to neighborhood customers. He saved money from various service-industry jobs and eventually opened up Delicias del Catrachito with the support of his mother, friends and family.

“I always had an objective to open up a business,” he said.

Catracho identifies any person of Honduran background, whether you’re here in America, Honduras, or elsewhere. For me, it’s a warm feeling to spot another Catracho in a city where we are far and few.

As of 2016, there are only about 5,000 Hondurans living in Chicago compared to almost 600,000 Mexican residents, so we are a niche Hispanic population, though Romero says he has a whole community of Catrachos living kitty corner from his restaurant.

“On the walls [of the restaurant], there’s a lot of signatures from Hondurans,” Romero said. “They all come here to eat… they come here for the festivals, and there’s a lot of groups.”

Tensions between established and new immigrants have been on the rise in Chicago, as many long-time Latin American immigrants and other Brown communities feel the focus on helping recent immigrants is unfair. The Hill staff writer Rafael Bernal explains that misinformation may be a large factor in this divide, as there isn’t an established difference between the recent asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants. Asylum seekers are immigrants fleeing home countries due to political persecution and human rights crises, while undocumented immigrants may experience less necessity and pressure to leave their home country, often doing so by choice.

Many Black and established Mexican immigrant communities are also upset over the quick plans to shelter new asylum seekers, with a plan to build a shelter causing a protest in Chicago’s Brighton Park. Due to environmental safety concerns, the plan has been canceled.

Romero believes solidarity is what helps combat the xenophobia many new Hispanic immigrants are facing in Chicago from other Latin Americans. He finds that solidarity between different Latines during his immigration journey is scarce in America.

“It would be good if all Central Americans and Latinos joined together because there’s strength in unity,” Romero said. “When I came over here, immigration would try to chase us and send us back, but we ran. I ran into a swamp, and you know, when you run into a swamp, it pulls you down, so this man grabbed my arm and said, ‘Brother, let’s go!’ There, that’s truly when you see the unity of Latinos.”

In Honduran culture, contemporary dance isn’t a widely practiced dance form, as traditional dances such as “punta” and “ballet folklorico” are most common.

Romero boasts happiness and pride for his Catracho heritage despite his arduous journey to Chicago. Catracho is a special word for Hondurans, including myself, because it is exclusive to our culture. Catracho identifies any person of Honduran background, whether you’re here in America, Honduras, or elsewhere. For me, it’s a warm feeling to spot another Catracho in a city where we are far and few.

“Catracho is the pride,” Romero said in Spanish. “My hair, my color, that’s an aspect you don’t lose…Our culture is spectacular regarding the food, our music, our drinks… Where would I be born again? I’d want to be born in Honduras.”

On the opposite spectrum of traditional cooking, professional dancer Wilfredo Rivera offers a particularly unique perspective on growing up as a Catracho immigrant. Co-founder and artistic director of Chicago’s Cerqua Rivera Dance Theatre, Rivera migrated from San Pedro Sula to New Orleans, then to Chicago at age 12 with his parents. Coming from a musically inclined family, embers of dance and art always kindled within him.

“I come from an artistic family,” said Rivera. “From a young age, I showed abilities for movement, a very natural instinct.”

In Honduran culture, contemporary dance isn’t a widely practiced dance form, as traditional dances such as “punta” and “ballet folklorico” are most common. Rivera says integrating modern dance styles allowed him to explore new horizons for telling his personal stories through movement.

In 2019, he opened his show “American Catracho,” which follows his migration story through dance. He plans on reopening it in February 2024 to remind Latinos in the city that there is no one way that immigration stories and experiences look.

“American Catracho is semi-autobiographical,” he said. “Opening up this conversation about the different layers and complexity of immigration and what it means emotionally, intellectually, and physically.”

Not only does the choreography of his dancing relay the emotions behind his story, but the music as well. Rivera believes his show provides a more intimate and engaged experience with theater.

“Latinicity comes into play like that…that feeling of the song, the voice — when you hear the violin, when you hear that percussion, the floor rumbles beneath you,” he said. “Those elements make you feel connected to what’s going on in front of you as opposed to just a spectator. You feel like you’re part of the experience.”

Building upon this idea, Rivera aims to introduce younger audiences to the beauty and importance of making theater accessible for the people its stories are about. He said he wants Latinos and all people in Chicago to experience an intimate performance of storytelling through his dancing.

Broadway in Chicago and New York has become a place for beautiful masterpieces. Still, many shows are expensive. As an avid musical theatergoer, I’ve spent well over $100 to see my favorite musicals. While I have the privilege to do so, many BIPOCs cannot afford to see performances about their own cultures.

American Catracho. Photo courtesy of Leni Manaa-Hoppenworth.

“One of the challenges is to bring the larger community… these folks that normally don’t know that they are welcome in the theater, that they are embraced by companies like us,” Rivera said.

He draws from his own isolation as the only Honduran dancer growing up in his dance world, recalling the pivot he intends to make from this experience.

“All of my professional training and my professional life, I’ve always been the only Latino, and for sure the only one [Honduran],” Rivera said.

With this in mind, he also says there’s the benefit of endless exploration and ownership of his stories.

“For us to take our narratives and have agency over them, to build them into real stories and pieces of art,” he said.

Whether it be through delicious food or lively dance, Catrachos young and old remain culturally embedded in Chicago’s ethnic history. We make up a small percentage of Hispanics here, but we make our mark.

For Rivera, being a Catracho holds many deep layers and explorations of selfhood that differ from person to person. As is reflective of the complex and challenging path to America, the cultural adjustment and search for identity can be just as daunting in a country where Western assimilation is encouraged in the “melting pot” of America.

“When I was in my late teens, early twenties, there was a substantial division between American whiteness and being an immigrant and Latino, and all the baggage that came with that,” said Rivera. “This continuous search for identity and us, the acceptance and complexity of our identities, is beautiful.”

Though I am American-born with only 15% Mayan blood, being a Catracha (feminine conjugation) means holding onto that 15% tightly, even if my Spanish is broken and my Iberian roots are larger.

I love visiting the homeland because my tias (aunts) still give me cheek-to-cheek kisses, because the mangos that hang from the trees are the juiciest ever and because of how beautiful the rows of pink pastel homes look climbing the mountains. I love holding macaws on my arms and visiting the cerulean seas of Roata; I even like watching the bats fly inside the muddy caves despite the heart palpitations it gives me. I love being a Catracha.

Whether it be through delicious food or lively dance, Catrachos young and old remain culturally embedded in Chicago’s ethnic history. We make up a small percentage of Hispanics here, but we make our mark.

For older generations like Guzman, forgetting home is still something she considers often, a deep yearning despite her appreciation for moving here.

“We parents of foreign birth continue to fight to help and protect what we built in a foreign land and we never stop missing what we left behind,” she said in Spanish. “I thank this country for all the opportunities it gives us every day.”

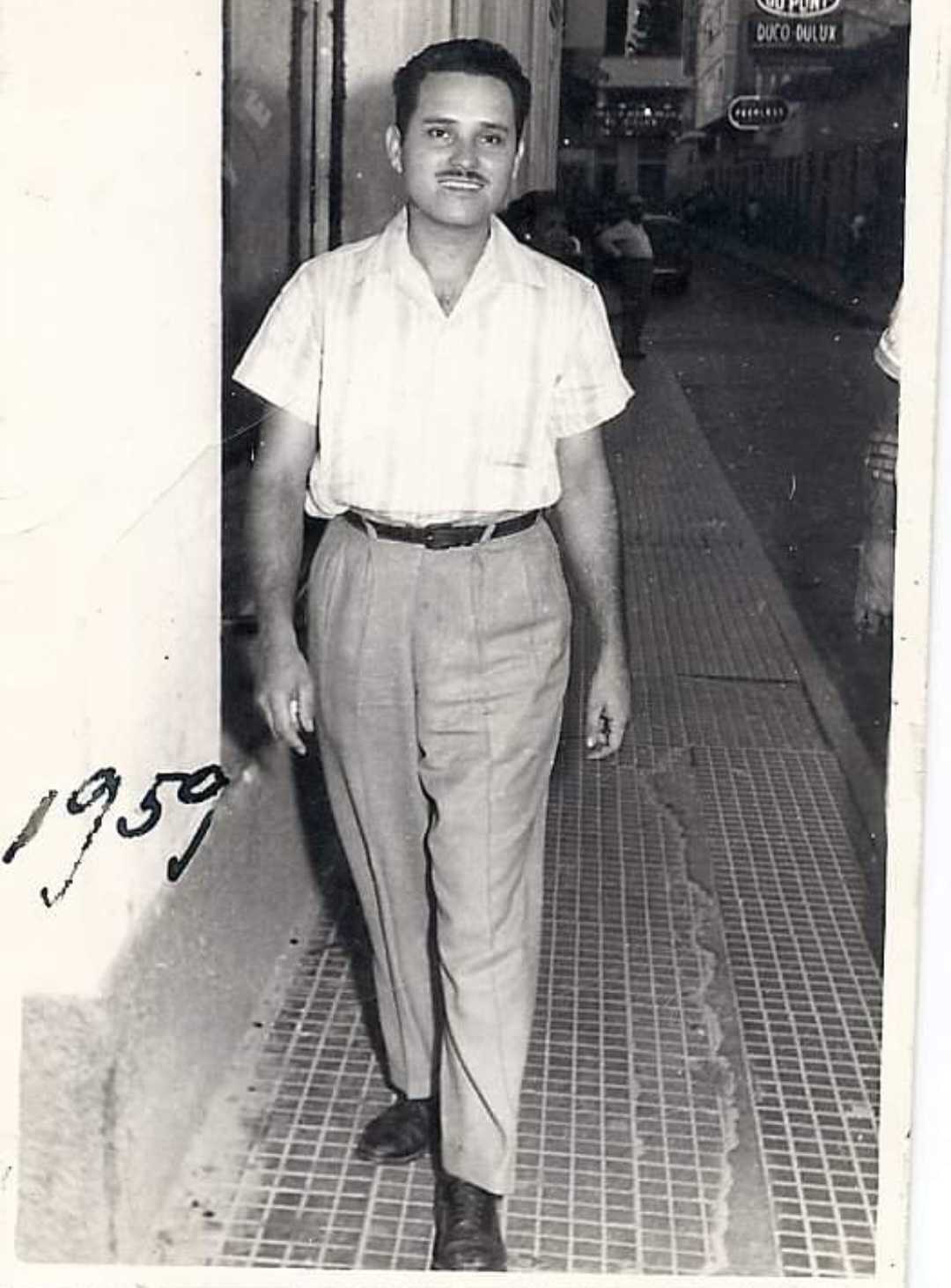

My abuelo in Honduras, 1959. Photo courtesy of Arnold Diaz.

Though I could never meet my Abuelo, my father tells me of all the immense pride he felt for being a Catracho among a sea of different cultures here in Chicago. He received many awards for his service in the Honduran Society, and while the organization has dissipated, its cultural legacy still fills the hearts of Catrachos all around Chicago.

Header by Rafa Villamar

NO COMMENT