Reconnecting With Our Lost Heritage

Lorena Buñi,who works as facilitator for Anakbayan Chicago, a mass group for Filipino youth, asks the crowd at APIDA’s (Asian Pacific Islander Desi American) Baybayin Workshop how many people know anything about the colonization of the Philippines. Silence deadens the crowd as the majority-Filipino audience keeps their hands down, searching around to see if anyone has the answers.

Centuries upon centuries of colonization by the Spaniards, the Japanese and the United States have tried to displace us and stomp out every vestige of our individuality: punishing our ancestors’ way of living and worship, burning our history written on bamboo and destroying our cultural artifacts.

Due to this, some Filipino immigrants and Filipino Americans tend to feel disconnected from their culture, including myself. As I was growing up in my suburban town, I was typically the only Filipino in my class. Almost all my friends were people of color, but even then, I still felt out of place. So, I tried to assimilate. As I described the nature of my upbringing to Buñi, her eyes lit up and she nodded.

“I cannot tell you how many times I have heard that story from many Filipino immigrants,” Buñi said.

Attempting to reconnect with my culture, I attended the Baybayin workshop held by the APIDA Cultural Center, DePaul University’s Asian student organization. The workshop was held in partnership with Anakbayan, a student youth organization aimed at mobilizing Filipino youth to stop the dictatorships in the Philippines.

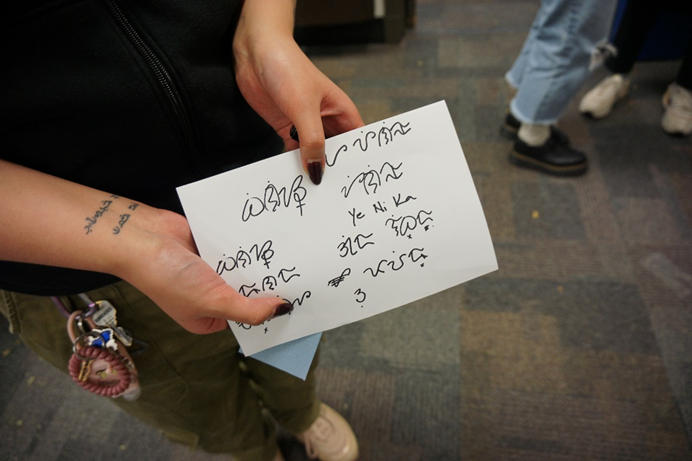

According to the workshop, Baybayin is an ancient Filipino written script. It was used during the 16th and 17th centuries before being replaced with the Latin alphabet due to Spanish colonization. Going into the workshop, I had no idea that Baybayin even existed, and I was intrigued. But a lot of people wanted to learn Baybayin and did not know where to access the information, according to Buñi.

Baybayin Writing. Photo by Sarah McFeely, 14 East Contributor.

“I was interested in learning Baybayin, and other people wanted to learn it, but there was very little information,” Buñi said.

Marcela Erickson, the APIDA community engagement assistant/social media coordinator. said she wanted to organize an event to educate others about Filipino Indigenous culture, as she is half Filipino herself. Erickson helped plan the Baybayin workshop.

“Coming into a higher education space, I found it really important to connect with my culture,” Erickson said, “I think we have such a beautiful heritage and culture.”

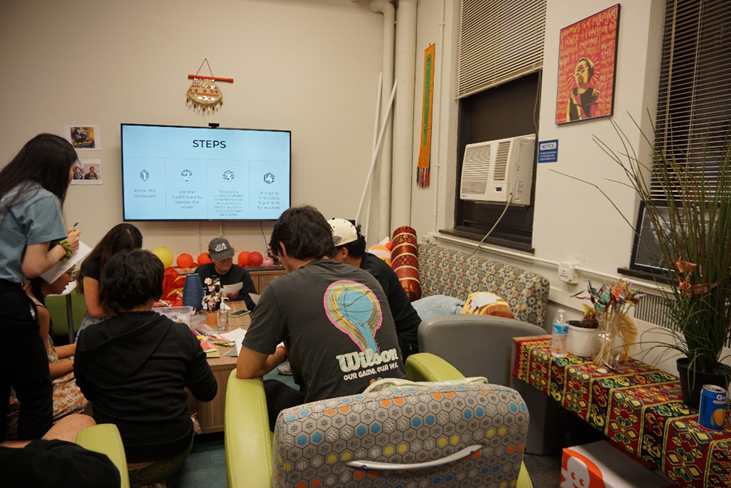

The first hour was spent socializing and eating Filipino food: lumpia, pineapple juice and pancit. The APIDA Cultural Center at DePaul had a very warm and inviting feel to it. Any anxiety and imposter syndrome that I had walking in washed away as I was surrounded by pillows, stuffed animals, blankets and my native food. I was at home, despite trying so desperately to run away from it all my life.

APIDA Cultural Center. Photo by Sarah McFeely.

Many people who attended the workshop talked about their struggles with connecting to Filipino culture. Emily Hutarte, an attendee of the workshop, said she never learned how to speak Tagalog, despite being Filipino.

“I’ve always wanted to learn Tagalog because I never knew how to speak it,” Hutarte said.

Hutarte is not the only one who experienced a cultural disconnect. After my family immigrated to the United States, the kids they had, including myself, never learned Tagalog or struggled to speak the language.

My cousin, Erin Baltazar, immigrated to the United States when she was five years old, and only spoke Tagalog. Now, she struggles to speak her native language because she needed to learn English.

“Since I haven’t practiced speaking it as much, I have a hard time responding in Tagalog,” Baltazar said.

In my family, there was such a strong pressure for everyone to assimilate into the American lifestyle. I remember my mom telling me to not stay out in the sun too long because it would turn my skin dark. I remember circling “white” on all my forms for school because I thought being Filipino was a mark of shame. A mark that I could never wash off because no matter how much I listened to rock music and ate pizza, I would still be brown.

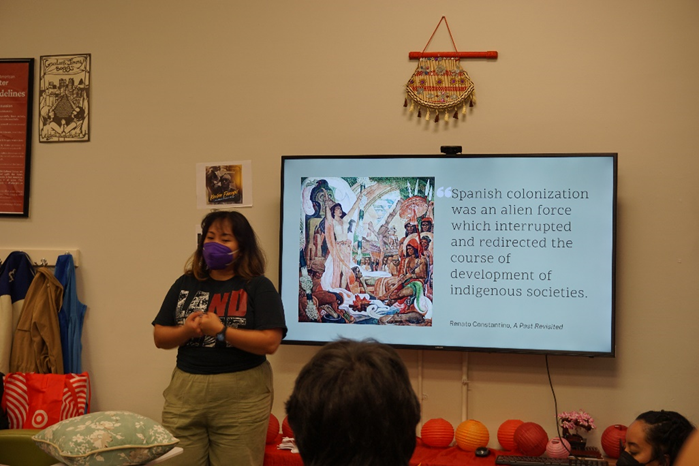

One point they emphasized during the history lecture is that Indigenous communities still exist in the Philippines, and they are still struggling to hold onto their land to this day. At the workshop, they said the increasing number of deadly typhoons are directly caused by climate change and the constant excavation of the Philippines’ natural resources.

Janessa Juntilla (Yellow jacket) presenting Indigenous Filipino communities. Photo by Sarah McFeely.

“Resources mined from Indigenous land don’t stay in the Philippines, they go elsewhere,” Chicago Anakbayan Facilitator Janessa Juntilla said.

China, Japan and the U.S. have all taken natural resources from the Philippines, and the Filipino natives are paying the price.

In 2011, Buñi’s grandparents and their cousins got hit by Tropical Storm Sendong, while she was still in the U.S. She described the logs piled on top of mountains rolling down, causing landslides and crushing people.

“If you were asleep around 11 p.m., which most people were, chances are they didn’t make it,” Buñi said.

Many people lost their lives, and others were never found again.

“You were lucky if you were able to find your loved one, because a lot of the bodies got washed away in the shore and some bodies weren’t found,” she said. “And some bodies were covered under debris, water, soil and logs.”

Buñi’s grandparents survived, but her first cousins twice removed did not make it. The hardest part for Buñi was not realizing she was seeing her cousins for the last time.

“They said, ‘Don’t say goodbye, we’re gonna see each other again,’ and the next time I saw them they were already in coffins,” Buñi said.

Feeling helpless and defeated, Buni went back to the Philippines to be there for her family. “I promised myself when the next typhoon hits, I would do my best to go back home on a medical mission.”

When she went back, she met an Indigenous community that changed her life.

Lorena Buñi presenting at the workshop. Photo by Sarah McFeely.

“I took away more than I thought I would from the people that taught me so much,” she said.

From that moment on, after meeting the Indigenous community, she became very passionate about Indigenous Filipino rights, children’s rights and environmental justice. She felt it was important to educate others, which is why she started Anakbayan.

Despite the killing and the rampant displacement of many Filipinos, the resistance is strong. People like Buñi, Juntilla, Erickson, the Filipinos who attended the event and the Filipino Indigenous communities actively protesting are all fighting in their own ways to not let Filipino culture fade away.

Now I wear my Filipino mark proudly on my brown skin, struggling to make up for all those years of whitewashing and brainwashing. Resources like Anakbayan and the APIDA Cultural Center have been a good first step, as other Filipino immigrants come together and learn more about our shared, beautiful heritage.

During her presentation, Buñi shared what she wanted people to take away from it, “Growing up in the Philippines, I remember learning that if it wasn’t for the Spaniards, we wouldn’t be a civilized country. We want to change that narrative.”

Header by Julia Hester

NO COMMENT