What dedicated bike lanes and bike paths can do to transform Chicago and cut its emissions.

Cyclists riding in a protected bike lane in downtown Chicago. Photo by William Frankel.

On June 2, 2022, a 2-year-old boy named Raphael Cardenas was killed on his neighborhood street. A car using the street as a cut-through struck him while he rode on his mini-scooter. On the same day, Bike Grid Now hosted their first bike jam advocating for safer infrastructure by blocking lanes of traffic. Their goal was to protect pedestrians and cyclists from traffic-related injuries and, in the worst cases, deaths.

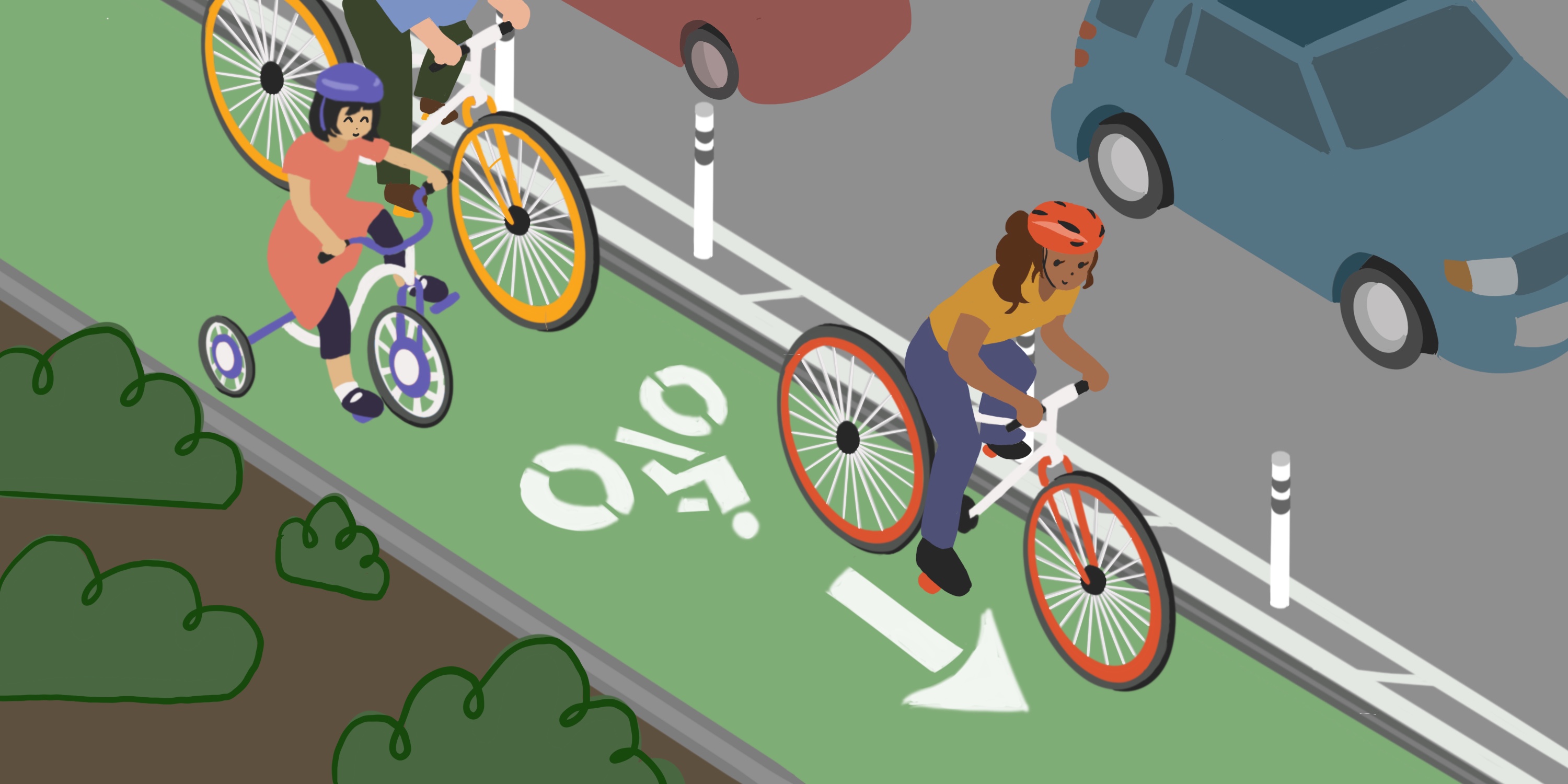

As the desire for cycling as an alternative mode of transportation to cars increases in Chicago, activist groups are pushing the agenda for safer and more practical street design. Learning about the different types of bike-friendly infrastructure and how they benefit the cyclists as well as the drivers is important to understanding why certain activist groups are hoping for a revamp of Chicago roads.

How divided paths from the street create a safer environment for cyclists, pedestrians, and drivers. Photo by William Frankel.

Cyclists face struggles that force residents off the road who wish to participate in zero-emission transportation. “I definitely feel safer on the lakefront trail,” explains DePaul student Puck Hubbman, who uses their bike as transportation. “On the road, especially in Chicago, car drivers tend to be aggressive.”

Bike Grid Now and Better Streets Chicago are two organizations that are fighting for the redesign of Chicago streets. Organizers at Bike Grid Now hosted an event on October 8 that created a human divider that blocked the bike path from the street on the 1800 block of North Halsted. This is one of many movements that they organize to bolster their slogan: “Paint is Not Protection.”

Each year, hundreds of cyclists are involved in severe traffic collisions that are incredibly dangerous, while drivers are left unharmed. The plea for safer infrastructure derives from incidents like these as well as general interest in making cyclists feel more comfortable on the streets.

“Something we don’t have a lot of here in the city are protected intersections,” Courtney Cobbs, a representative from Better Streets Chicago, described. “This is where barriers are kind of placed to slow drivers down when they’re making turns. It helps shorten the distance where pedestrians are exposed to car traffic.” Adding barriers that separate cars from bike lanes and sidewalks make cycling and walking safer, in turn creating a street focused on accommodating everyone rather than primarily cars.

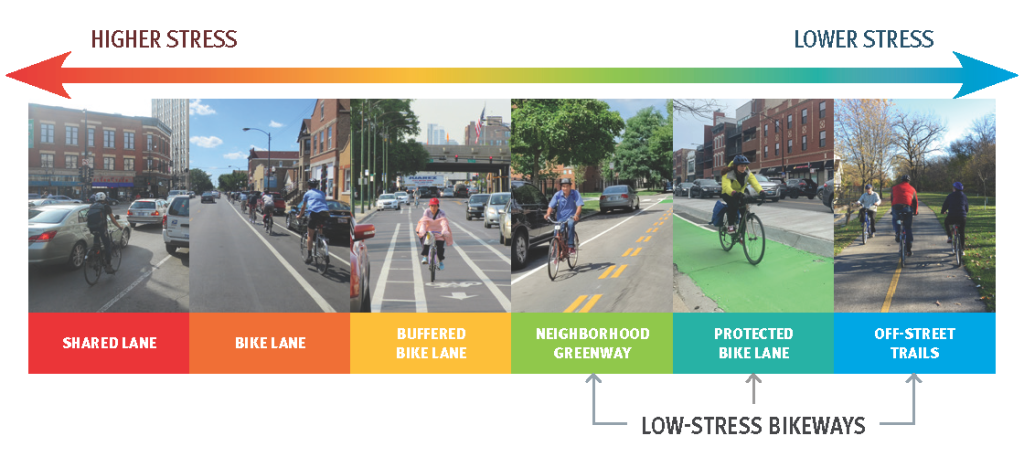

Different types of bike infrastructure. Retrieved from Chicago Department of Transportation.

One of the major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions throughout the world is transportation. Shipping far distances, air travel, and daily excessive car use are the main reasons why transportation emissions are so high. The only solution is reduction.

As there are substantial amounts of greenhouse gas emissions from cars, cycling seems to be an efficient and sustainable mode of transportation. In 2013, Chicago began the implementation of the Divvy bike-sharing program which has furthered the need for bike-centric road design. In the ten years from Divvy’s beginning in October 2013 to October 2023, Chicago partnered with Lyft to add 870 stations. There is additionally an increase in ridership. Ten years ago in October, Divvy saw a total of 174,694 riders and there were 452,696 riders this past month.

It is very difficult to measure the total number of cyclists on the street, so Chicago doesn’t record the data. The best quantification of active cyclists in the city is obtained from Divvy ridership which also shows the majority of users are members rather than one-time riders.

Woman uses Divvy bike sharing system in downtown Chicago. Photo by William Frankel.

Because citizens want to ride bikes for various reasons, the accommodation for that desire is a growing issue. “We’re really advocating for the vulnerable who can’t get out there and use the streets because the streets aren’t safe,” Carl Beien, a representative from Bike Grid Now, described. Cars can be very expensive to own and operate for an individual, including costs for gas, insurance, registration, repairs and sometimes monthly payments. When the options for transportation without cars are minimized, it ostracizes people who can’t afford these costs.

The main concern brought up when discussing the redesign of Chicago streets to be safer for those outside of cars is the cost. While creating protected bike lanes or raising crosswalks to slow cars would be expensive, it is not nearly as expensive as infrastructure made for cars.

Car blocks bike path where dividers are missing due to an alleyway entrance. Photo by William Frankel.

Illinois and the city of Chicago recently completed the Jane Byrne Interchange intended to reduce traffic and speed up travel times into the city. This infrastructure advancement cost the city $804.6 million. “When it comes to paying for vehicle infrastructure, blank check,” explains Beien, “but then when it comes to paying for safe streets infrastructure, we pinch pennies.”

Often when cities introduce infrastructure that is safer for cyclists and pedestrians, car drivers appreciate the change as well. People in vehicles often worry about accidents involving cyclists and pedestrians. Having a more divided space eases the stress they face when driving down streets with lots of foot and bike traffic.

Cyclists manage the intricacies of current intersections even with dedicated bike paths. Photo by William Frankel.

Another solution that Chicago has implemented quite well, but could use improvement, is diverting car traffic to arterial roads designed specifically for cars. According to Beien and Cobbs, allowing cars to pass through neighborhood streets or roads with lots of commercial activity increases the dangers for those not in vehicles. This is solved by one-way streets in neighborhoods and decreased accessibility for cars on streets with many businesses. However, for this solution to function adequately, it’s crucial that cars have access to alternative routes—that are often quicker than neighborhood and commercial streets—to get to the same destination.

To prevent more traffic accidents causing injury or death, a change must be made. The death of Cardenas is not isolated and similar events happen more frequently than they’re reported. Helping the cause to create safer streets for everyone is easier than some think. Given you are able, Beien says, for journeys that travel fewer than one mile, walk. For journeys fewer than three miles, ride a bike. “The number one best thing you can do is get out of a car,” according to Beien. “Do not participate in car culture as much as you possibly can.”

Header by Sophia Johnson

NO COMMENT