What Tetris, a 5K and a 350-year-old math problem taught me about the long road to getting better

Jayne Secker’s on-air remarks about Willis Gibson, the first player to beat Tetris – Sky News

Lakefront Trail at Fullerton Ave. Photo by Varun Khushalani.

Running just sucks. There’s just no point to it. It’s a constant string of voluntary pain, all to get right back where you started, just a little bit more tired. In 2023, I worked outside all summer on the tennis courts off Waveland Avenue, watching runners drift by all day. I didn’t understand what could be at the end of their journey that was so worthwhile.

But I’ve known a lot of runners in my life, all sharing this deep connection to a pastime that fulfilled them. Running made sense to them. One day that summer, I wanted to find out why.

On that first run, I went a lot further than I expected. I slowly began to fall in love with running in the warm sun, long stretches slowly gliding past tall buildings towering above me. And it hurt like hell every time. During the week, I was consistently running the Lakefront Trail, picking fights in my brain, trying to find more gas in the tank. After a particularly good run, I wanted to push myself. If I could go at my usual pace for two miles longer than my previous best, it was possible to run 13.1 miles in two hours; 6.55 miles up and down the coast from Fullerton Avenue. The next day I went out and tried.

By mile five, a sharp pain had crept into the front of my left foot while the other drifted in and out of consciousness. 6.55 miles gets you past Navy Pier, down the length of Grant Park to Roosevelt Road. It was fun looking off in the distance at places I’d always taken the train to. By mile nine, my left foot felt as if it were stepping repeatedly on a nail and my right foot was numb up to my shin. But I knew I could go a little longer.

Miles 10, 11, and 12 I don’t remember at all; my brain strategically shutting down to stay focused. I was desperately searching for a rhythm, pushing down the pain as best I could.

My brain turned back on as my running app told me I had 1.1 miles to go. I love finish lines. At the end of this ordeal, I was reaching the stretch I had begun to run in my dreams, sprinting up the last slight curve to the fountain at Fullerton Avenue, past the short trees and rude ducks.

“13 miles completed. 0.1 mile left to go.” The end was 528 feet in front of me, in a spot I couldn’t see; all I knew was that I had to give it everything. I didn’t feel my shoes touch the ground until I heard the last alert.

I slowed to a jog, my body decelerating on its own accord. I rummaged through my pockets for my phone. It took me far too long to find my time. 1:59:41. I took a breath and raised my hands in the air, my heartbeat slowed down as I turned to walk home

~~

In October of 2023, I did almost everything to sign up for a 5K in November. After the half-marathon, I wanted some proof it wasn’t a fluke. I picked another goal to reach: a 5K (3.1 miles) run in under 18 minutes. I don’t know how I got that calculation, but it felt like the right finish line to motivate me. I paused at the checkout page for weeks, though. I didn’t want to pay unless I knew I could run that fast.

I downloaded a four-week 5K training plan in my running app. The first day was an interval run that was boring and difficult, but I trusted that the app would lead me in the right direction. The second run was supposed to be a recovery run. I had consulted a physical therapist for a growing sharp pain on the side of my right foot, but it was only inflammation, just painful until warmed up. To loosen everything, I set a timer for 25 minutes. No mile or speed goal, just running — that’s when it was the most fun.

The first mile, every sluggish step felt like a punch to the body. I began to slowly accelerate, hoping that maybe going faster would feel better.

As 15 minutes passed, I realized I was reaching a pace I’d never attempted long-distance, and still, slowly accelerating. If you were in DePaul’s Ray Meyer Fitness and Recreation Center, on the fourth-floor indoor track, at around the time I was pushing for the last ten minutes, you would have seen the entire skyline of Chicago light up while the orange sunset slowly slid off the highrises. In the last five minutes, I wasn’t feeling pain anymore, I just wanted to see how fast I could go.

After my timer went off, I knew somewhere in that dangerous exercise was 3.1 miles where I was moving faster than ever before. I stopped sharply on the track and stopped my cooldown early.

“Congrats, you have earned your PR in the 5K.” 17:53. I felt a strange sense of relief as I paid my 5k entry fee. After that run, I only did one more lesson of the four-week training program. What else was there to do?

A month later, I left a Diwali party in Oak Park early because at 6 a.m. the next morning, I had to be in Grant Park for my adventure. The sunrise from the Uber was nice to watch; stepping out it was a little breezy.

At the starting gate, I looked up at familiar buildings and daydreamed about sunny days. I had spent the last 30 minutes before doing everything to warm up; I wanted to find the right rhythm when I got off the line. As we lined up, I queued the 18-minute-long playlist I’d made with songs placed at strategic moments for energy. (Not wanting to tempt fate, I padded the playlist to 20 minutes.) The first group went out and we took their spots. Those last moments were painfully quiet as everyone put their heads down, quickly searching for something within themselves before the gun went off.

All of a sudden, runners were bumping into each other and the walls started closing in. The first tenth of a mile was pure chaos. The skyline disappeared as I ran down into tunnels I’d never seen before, blocked off for just this race.

As I hit the first mile marker, I knew I was going at least a minute and a half slower than I needed to be. My running app wasn’t telling me anything and I was hitting the one thing I’d never experienced in this city: elevation changes. Just to try and go faster, I picked out runners in the crowd and chased them down. But even then, I was speeding up and then slowing down, destroying myself just to try and make it to the next street.

And I still wasn’t going fast enough. “Gonna Fly Now,” the theme from Rocky by Bill Conti (my victory song), ended before I hit the third mile marker. I yelled at myself, begging to go faster. I needed to be going faster. Before the last turn at the end of the third mile, I had nothing left in the tank.

But one more corner, though, and I knew I would have a finish line to chase — that was my moment to recover. I picked one last runner in front of me, some high schooler in a gray hoodie. Turning left onto Columbus Drive, the third mile marker finally appeared, and 528 feet behind it stood the final stretch. I just wanted to be at the end, to be done with this painful exercise. Sprinting to the line, I pushed to what I know is 100%.

And I was still too slow.

I didn’t beat the kid to the finish. I looked up at the timer and saw 22:something. That couldn’t be right. I texted my family for my real score. 21:22.

Someone handed me a medal that I stashed in my pocket on the walk back home. I didn’t earn it. I was supposed to be able to run three minutes and 30 seconds faster. I put on a jacket to cover my race bib. I was supposed to run past the line with my hands in the air, but I sat alone in Grant Park, 22nd in my age group and 132nd overall. I would have to do it again, I told myself on the depressing walk home; the only way to move forward was to try again. I threw my shoes in my closet, took a cold shower and a long nap. I was done for the day.

It’s March now. I’ve run a few times on the treadmill since. Every time, I’ve slowed down a few miles before I reach my goal, which gets shorter and shorter each time. But what can I say, I’m not a runner. I hate running.

Photo by Varun Khushalani.

***

Fermat’s Last Theorem

“the first seven years I had worked on this problem I loved every minute of it however hard it had been. There had been setbacks, things that had seemed insurmountable but it was a kind of private and very personal battle I was engaged in” — Andrew Wiles, in the BBC documentary, Fermat’s Last Theorem”

In June of 1993, Andrew Wiles, a British mathematician, presented a lecture series at Cambridge University. He was about to prove the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, an idea posed 30 years earlier by two Japanese mathematicians who had found a connection between two very separate fields, the study of shapes and the study of whole numbers. For the seven years before these lectures, Wiles had been working on the cutting edge of 20th-century mathematics. Under any other circumstance, changing the fabric of math would be a career-defining achievement. But when he finished his series, he wrote a statement at the end of his proof that would change the legacy of mathematics forever:

“implies FLT.”

In 1637, Pierre de Fermat, a French lawyer with a deep reverence for mathematics, wrote in the margins of Diophantus’ Arithmetica that: “It is impossible…for any number which is a power greater than the second to be written as the sum of two like powers [x^n + y^n = z^n for n > 2].” If n=2, then the equation has an infinite number of solutions, as stated in the Pythagorean Theorem. For any whole number greater than 2, no combination of x, y or z would make the equation true. He writes in this book, “I have a truly marvelous demonstration of this proposition which this margin is too narrow to contain.”

Fermat dies before he can reveal his proof. His son, Clement-Samuel, published the notes and unsolved proofs from all his father’s books to the public. Mathematicians had proven almost every single one of Fermat’s unsolved proofs, but this seemingly simple claim was becoming so ubiquitously unsolvable, that it earned mythological status in the world of mathematics.

Fermat’s Last Theorem. FLT.

Wiles discovered Fermat’s Last Theorem at the age of 10. When walking home from school, he discovered a book called The Last Proof detailing the story. Even at that age, he could understand the basic foundations of the deceptively simple theorem. Thirty years later, Wiles had strung together a sequence of complicated, new and abstract ideas in mathematics, finally answering one of the greatest questions in mathematics. Unknown to him, it was all about to be ripped away.

~~

In August 1986, at the International Congress of Mathematicians, Ken Ribet, a math professor at Berkeley, had a stroke of inspiration connecting Taniyama-Shimura and Fermat. Ribet found that proving the conjecture would inevitably prove the ancient theorem. “There were thousands of mathematicians at the International Congress,” recalled Ribet, “and I sort of casually mentioned to a few people that the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture implies Fermat’s Last Theorem. It spread like wildfire and soon large groups of people knew, and they were running up to me asking, ‘Is it really true you’ve found a link to Fermat’s Last Theorem?’ And I had to think for a minute, and all of a sudden I said, ‘Yes, I have.’”

When Goro Shimura and Yutaka Taniyama proposed their conjecture in 1955, they didn’t realize that their idea of connecting modular forms to elliptical curves would be one of the most important breakthroughs in the 20th century. This abstract idea was the basis of an ever-growing world of mathematics, but up to that point, mathematicians had been unsuccessful in proving the connection that Taniyama and Shimura had proposed decades before. Top academics, including Ribet, didn’t pursue the difficult path to solving the conjecture: “I was one of the vast majority of people who believed that the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture was completely inaccessible. I didn’t even think about trying to prove it. Andrew Wiles was probably one of the few people on Earth who had the audacity to dream that you can actually go and prove this conjecture.”

~~

“You enter the first room of the mansion and it’s completely dark. You stumble around bumping into the furniture but gradually you learn where each piece is. Finally, after six months or so, you find the light switch, you turn it on, and suddenly it’s all illuminated. You can see exactly where you were. Then you move into the next room and spend another six months in the dark. So each of these breakthroughs, while sometimes momentary, sometimes over a period of a day or two, is the culmination of, and couldn’t exist without, the many months of stumbling around in the dark that precedes it.” — Andrew Wiles, in the BBC Documentary “Fermat’s Last Theorem”

The day after his lectures, Wiles was on the front page of the New York Times. People named him one of the 25 most intriguing people of the year. His name was about to be etched into history. But when his work was reviewed by Professor Nick Katz, a colleague of Wiles’ at Princeton, an issue was found in his expansion of Kolyvagin-Flach, the portion of the proof used to connect Taniyama-Shimura and Fermat. After abandoning his previous graduate studies on Horizontal Iwasawa Theory, Wiles had been working on extending this newer approach for nearly three years — he thought it would be more effective at proving the necessary conditions for the problem. It wasn’t, and no matter how hard Wiles tried to fix the whole problem; it needed new thinking in mathematics.

“Somehow the expectation was, ‘You prove Fermat, and anything less you’re in trouble,’” — Peter Sarnak, a Princeton math professor and a friend of Wiles.

After months of no progress, Wiles employed the help of one of his former students, Richard Taylor, another expert in elliptical curves and number theory. They kept trying to fix the approach with localized attacks and fixing small problems, but according to Peter Sarnak, a trusted colleague of Wiles, the work of trying to go back and fix Kolyvagin-Flach was like trying to fit a large carpet in a small room; every time a solution came in one corner, problems arose elsewhere. Wiles described the problem as so abstract that, “Even explaining it to a mathematician would require the mathematician to spend two or three months studying that part of the manuscript in great detail.” Rumors were spreading about the potential errors in his proofs; other mathematicians began pressuring him to release his work so others could collaborate.

“I decided to go straight back into my old mode and shut myself off from the outside world. For a long time I would think that the fix was just around the corner, but as time went by it seemed that the problem just became more intransigent.”— Andrew Wiles

~~

On September 19, 1994, Wiles sat down at his desk to look over his work. He had faced almost a year of scrutiny at that point. He wanted to take one last look at his Kolyvagin-Flach approach and pinpoint what went wrong. He was checking over his work before the possibility of sending it out into the world, letting other mathematicians try to solve what he could not. Noam Elkies, a professor at Harvard University, had even proposed a counter-example to Fermat, which, if true, would render all of Wiles’ work useless. It was close to the end of his childhood dream.

And then, suddenly, the end found him.

As he looked down at all the work he had done on Kolyvagin-Flach, he realized that all the work expanding it to no avail had trained him to fix the same issues in Horizontal Iwasa Theory, the approach he initially abandoned. By implementing all the techniques he had picked up over years of tenuous effort, he could go back to the original work he had been developing since college. His proof could now be finally complete. After nearly eight years of work and a lifetime of mathematics inspired by a 350-year-old question, Andrew Wiles found the last piece of his impossible puzzle by going the wrong way.

I discovered Wiles after hearing him discuss his revelation in a BBC interview. He sits at an unruly desk; piles of papers surround him. He looks like you’d imagine any British mathematician would — unassuming. But as he spoke about his achievement, he had to stop for a moment, the words almost stuck: “… suddenly, totally unexpectedly, I had this incredible revelation. It was the most important moment of my working life. Nothing I ever do again will ever be as important … it was so indescribably beautiful, it was so simple and so elegant, and I just stared in disbelief for twenty minutes, then during the day I walked round the department. I’d keep coming back to my desk to see it was still there – it was still there.”

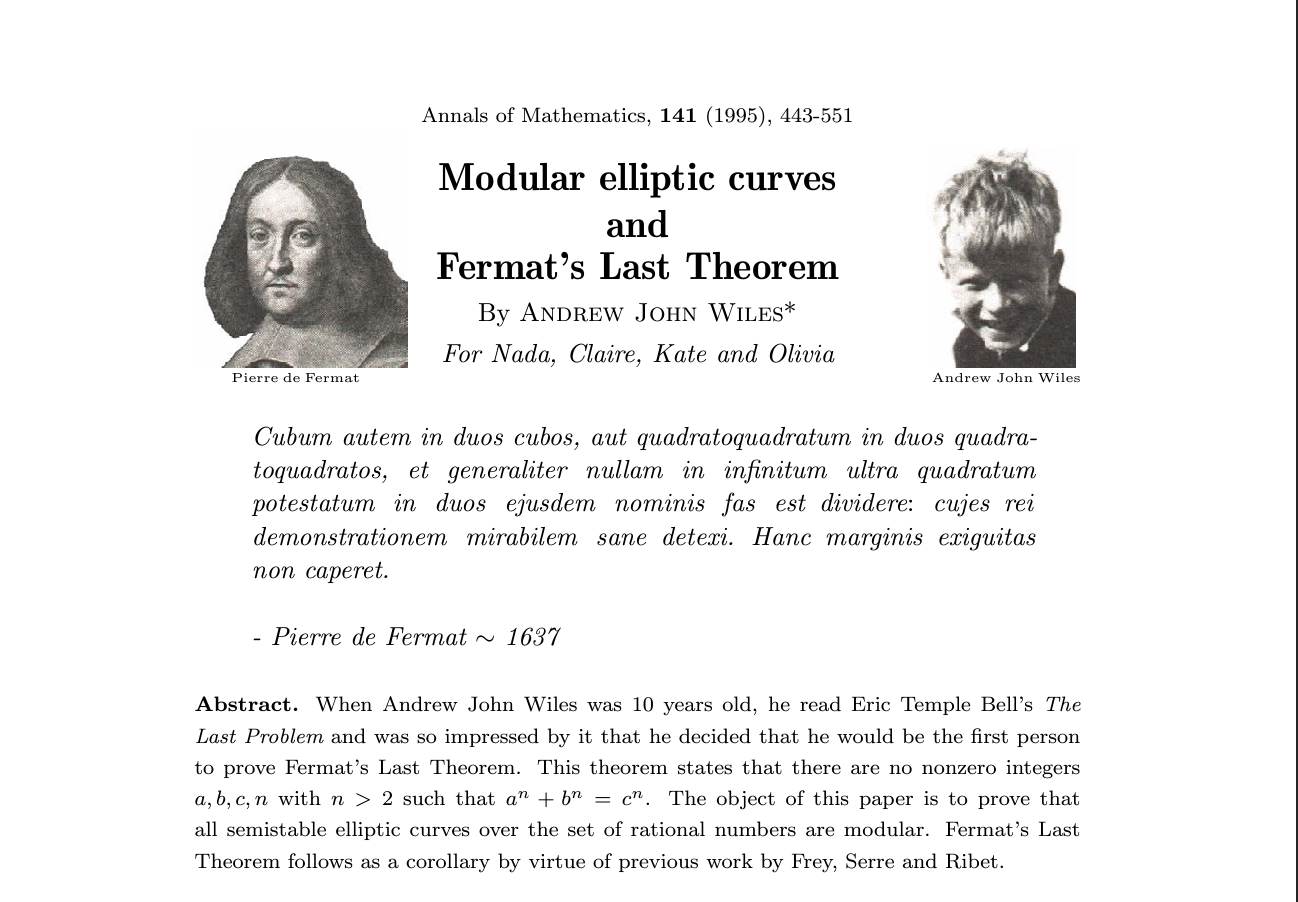

The front page of Andrew Wiles’ proof in the 1995 Annals of Mathematics

***

Life Goals

“Maybe I led you to believe that basketball was a God-given gift, and not something I worked for every single day of my life” – Michael Jordan

It’s the 2018 finals of the Classic Tetris World Championship — seven-time champion Jonas Neubauer versus the underdog, 16-year-old Joseph Saelee. Neubauer was the first champion of this event in 2010, as well as one of the first to achieve a “max out” score of 999,999, where the six-digit score counter can’t advance further. In 2018, he set another world record of 1,245,200 points, but this was not to last. Saelee was the new kid on the block, having popularized a new technique called “hypertapping.” The vast majority of Tetris users, including Neubauer, played with the common play style called Delayed Auto-Shift, or DAS: holding the arrow buttons down to move a piece from side to side. Conversely, hypertappers, like Saelee, rapidly tap the button to move pieces faster. Before then, it was nearly impossible for players to get past the “kill screen” of level 29, where pieces drop faster than DAS players could move them. Hypertapping allowed players to hold on at the speed of post-level-29 play. World records began to creep into the mid-30s, a few of them earned by Saelee. In the finals of his first appearance at the tournament, Saelee took every single game on his way to being the youngest player to ever win the CTWC. He won $1,000, a gold trophy and the future of competitive Tetris. I immediately downloaded a Tetris emulator right after. Saelee’s young skill made me curious to see how far I could get in this simple game.

You may know the rules of Tetris, but I challenge anybody to play a version of classic Tetris, made in the Soviet Union, by computer engineer Alexei Pajitnov, and later developed for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in 1989. There is no holding piece and the blocks are stiffer, immediately locking in place after touching down. Every 10 lines cleared, another level brings a new color palette and faster-dropping pieces (called tetrominoes for your information). At the end of your run, when you inevitably lose, you just have to restart and try again.

You lose a lot in this game. It’s addicting.

During the pandemic, locked in my room for 23 hours a day, I spent quite a bit of time playing this mindless game. Every turn, you chip away at a number you know will never matter; there’s absolutely no pressure, just progress. That’s when it’s the most fun. After a while, I was scoring in the mid-300,000s, by no means impressive stuff, but it felt gratifying to fight through each brutal run. Anytime I wasn’t playing on a screen, I found myself playing in my mind, trying to practice moves to use in the game. (Fun fact: This is a documented phenomenon called the Tetris effect, or in a broader context, the game transfer phenomenon. When playing this game for a long time, players begin to see blocks falling anytime they close their eyes. So, no, I’m not insane.)

I was particularly bored during one stretch of time in the pandemic, so I decided to enter a Jstris tournament (a different attacking/defending variation of the game) It was exciting being part of something like this with others who’ve found the same outlet.

The buildup was intense, and I practiced desperately before, trying to warm up.

It was silent in my room before the first matchup, a moment I never enjoy; it’s just me in my head, trying my hardest not to think about anything. Before the first match, I take a deep breath and stretch my fingers. It’ll be fun. Just like any other run.

In that first matchup, I lost four straight games in a row. I don’t even think it took 20 minutes. Take a wild guess at how much Tetris I play now.

~~

That was almost three years ago and while the game holds a symbolic spot on my already cluttered desktop, I completely disconnected from the world; I didn’t hear that an even newer technique of play style called rolling was evolving the game faster than hyper tapping. I didn’t hear that Saelee retired from competitive Tetris at the age of 20, holding 54 world records for the highest score achieved, the most held by any player to this point. I was shocked and saddened when I heard that Jonas Neubauer died of a heart attack at the age of 39. I was halfway across the world when I found a kid from Stillwater, Oklahoma, had beaten it.

~~

On December 21, 2023, 13-year-old Willis Gibson, known online as “BlueScuti,” was having the run of his life. Forty minutes in, and he had played nearly perfect Tetris to get to this point. Even on the livestream, you can see eyes darting up and down the screen from behind the glare coming off his thick, slanted glasses When he reached level 154, he had gotten further than any player in history, beating his own record of 153. He was over 100 levels and five million points ahead of Neubauer’s forgotten world record. No one else had ventured this far before. There was no sound in the room, except for the constant looping soundtrack that sticks in the head and refuses to ever come out.

Rolling meant players could play nearly twice as fast as the fastest hypertappers, giving them the ability to play consistently past level 29. Since the pieces never go faster after that point, now it was just a matter of how far players could go in a game trying to make you lose, forever.

Well, almost forever. Computer programs playing the games had found certain glitches in Tetris when they pushed the ancient game long past where it was designed to go. Level 29 was called the kill screen, but only because it was the closest thing to it; it was thought to be impossible to pass. These players and bots were going far past 29, exploring the infinite expanse of the never-ending stack trying to find one of the most private and oldest secrets of the game — where it ends.

Computer programs found the secret first. They were going so far, and so fast, that at certain points, there was a chance the game crashed. Since the code begins to die out after level 155, all a player has to do is play perfect Tetris at the highest possible level for 40 minutes straight to get to a point where the game can crash. Once they do that, they would have to then hit the perfect combination of piece clears to force the game to stop running off code, and switch to RAM, where it would immediately crash. If you miss that combination, the game keeps on running until you eventually lose, or find another perfect combo. Bots were playing games up to levels in the mid-200s. No fatigue for robots. Human beings were just getting strong enough to push into triple digits.

~~

Willis knew, just like every other Tetris player attempting this challenge, that going into level 155, he needed a single line clear to cause a game crash. But at 154, he messes up a little. These pieces are moving faster than you or I could think; Gibson’s just playing, trying to minimize, strategically burning lines to clear his stack down to the bottom.

He did it too well, scoring a triple line clear to move forward to level 155. His first chance to crash the game passed. “I missed it,” Gibson said. He gets through 155 relatively easily, but he’s in the dark now. He has to search around, just playing perfectly until he hits the right transition.

Or until he loses.

At 156, he pleaded with the game to crash. The pieces were falling perfectly so far, and the game still hadn’t crashed. He got to level 157, and his stack had risen a little higher than it should. He made two short mistakes, on either edge of the screen, forcing him to make a couple of quick moves, all landing in the perfect places. But Gibson hadn’t cleared any lines, just filled gaps — he needed clears to advance. He was at the end of the record-breaking run, and he knew it. He quickly moved a J piece all the way to the left and looked up for the next piece. It didn’t fall.

The theme song that had so reliably played for the whole run flatlined. A blank space loomed where Gibson placed his last piece. His goal for that stream was two million, posted under his face cam, written on the side in a simple white font. After that last clear, he reached a score of 6,850,560. It took him just under 40 minutes to clear 1,511 lines. For the first time in history, a player finished a game of Tetris without losing.

***

I went for a run the other day. It was just so nice out and I wanted to feel the sun and wind on my back again. I went on my usual path, down the Lakefront Trail from Fullerton Avenue, touching a point at Navy Pier, and then running back.

It was so difficult. I was searching desperately for a rhythm that I couldn’t find. I was going at my old long-distance pace, but I couldn’t sustain it. When I reached the halfway point, I was done. I couldn’t muster the strength to turn back.

Right before the trail crosses the river through Navy Pier, there’s a small beach hidden under the massive shadows of the city. I’ve seen it many times before, but I’d never stopped and stayed. I slowed down and walked down the ramp to the beach. My feet dragged as I morosely walked over the packed sand. The lake gently swayed, undisturbed by the sunlight gleaming brightly off it. I kneeled in front of the calm water, digging my feet a little deeper into the damp sand. I splashed some cold water on my face and my arms and legs. I was avoiding thinking about how much harder I had to work on the way back. But the slow, constant rhythm of the waves distracted me. My heartbeat calmed down and I took a breath. After a while, I waited for my body to instinctively stand up. It took me a couple more moments to remember I had to do it all by myself.

On a run in Marseille. Photo by Varun Khushalani.

****

Header by Varun Khushalani

NO COMMENT