The intrigue and importance of disappearing handmade crafts and art forms

It’s no secret that throughout human history there has been an intrigue within nostalgia. I mean, the word itself is derived from the Greek words “nostos” (return) and “algos” (pain or grief) some 300 years ago. I’d like to argue that nostalgia inevitably influences every facet of life, from comparing one past experience to the next, to recalling memories to make everyday decisions. It’s an idea that surrounds us, albeit perhaps a little differently than it did throughout previous generations.

In order to hear other people’s experience and stories regarding these ideas of nostalgia, I wanted to focus on crafts and art forms that are rapidly disappearing all around the world amid rising consumption rates and mass communication. Chicago has dozens of these craft makers all throughout the city, working day-in and day-out to create, repair and breathe life into objects that are slowly becoming obsolete among the world’s fast paced, consumerist lifestyle.

For this first installation of “Before It’s Nostalgia,” I talked to Kaspar Yardley, the owner of Stereo Rehab — a specialty repair shop for vintage audio equipment — and Simon Epelman, a longtime watchmaker who works out of Jewelry Row’s iconic Mallers Building, in an effort to explore the importance of keeping traditions surrounding crafts and art, both within the micro-scale of my own life as well as the larger avenue of human history.

Transcript:

I’m not totally sure if I can pinpoint the exact point in my life that I remember first thinking to myself, “Oh, old stuff is cool.” My dad always used (and continues to use) cameras as ways to remember things, and most of my mom’s old records are still in perfect condition. And thank god she also kept most of her old clothes because it was the first step I took towards building my own style. My grandpa is still able to fix anything at his apartment while my grandma’s sewing machine and cooking ware are old enough to have their own hours-long feature documentary. I only bring these seemingly mundane things up because they acted as a sort of doorway that helped me understand my family better while making sure that a past time wouldn’t be forgotten.

But it’s not about the idea of feeling and seeing something “retro” or saying some ridiculous phrase like, “I was so born in the wrong generation,” but rather, my intrigue of life is somewhere along the lines of “What is going to last?” and “What is going to happen when it’s gone?” I’ll leave it at that before I get too existential.

This being said, I wanted to talk to people who work with their hands, specifically those who work to repair, rebuild and sustain things. The experts whose crafts might seem underappreciated within the modern trend of rapid consumption and constant intrigue of the “new.” I like to say Chicago’s got everything, from modernity to tradition, and these “disappearing” crafts and dying art forms aren’t an exception. As they’re still around, I want to explore the importance of younger generations being aware of that, especially before it’s too late.

Kaspar Yardley: “So when somebody, your generation, or even let’s say 10 years out, They’re going to think, much like cell phones, iPods, and everything, it’s designed to be thrown away. Once a good design, always a good design, is my philosophy. So, if it was made properly in the first place, it will always be proper. If it’s made like crap, which most of it is, it’ll always be crap.”

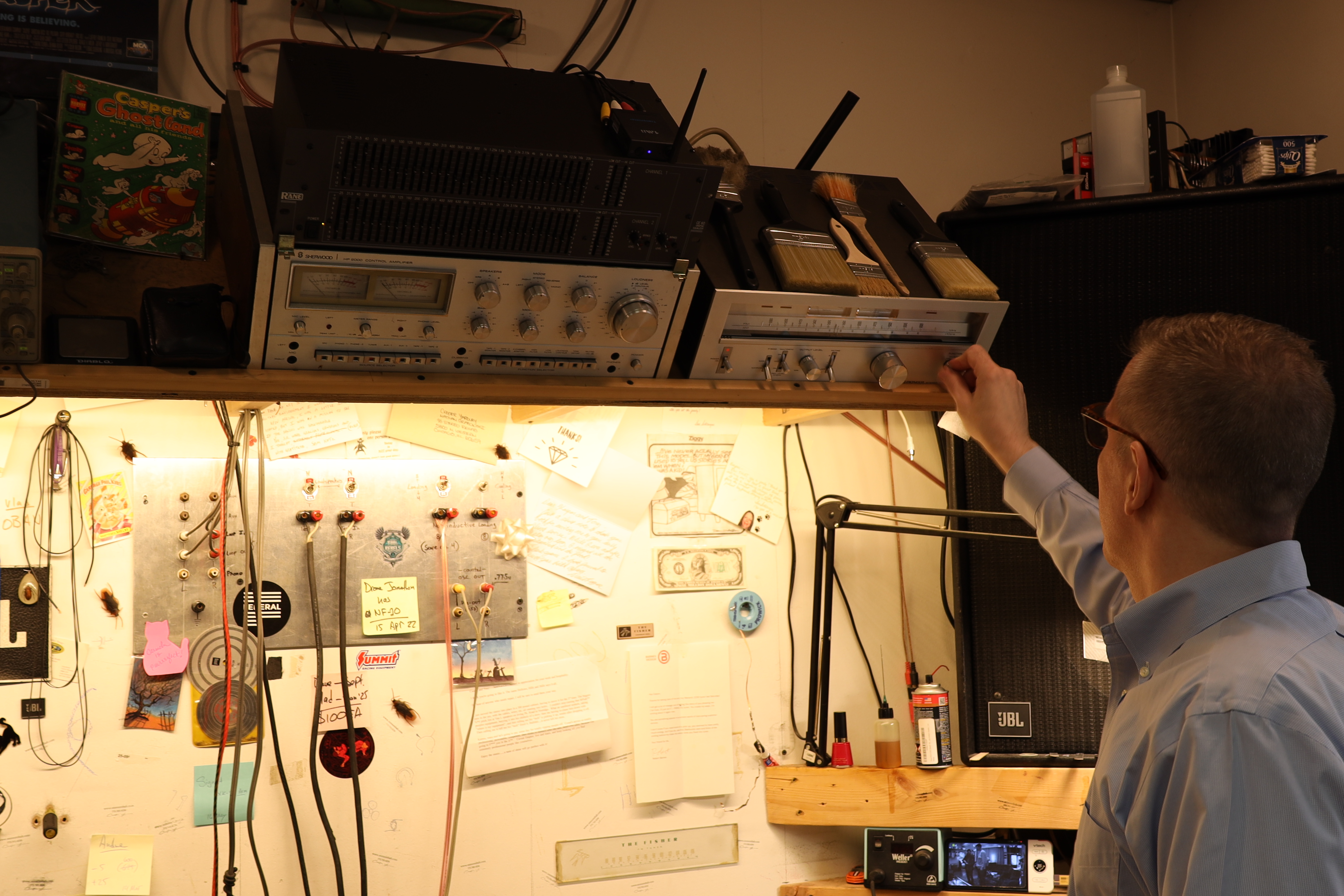

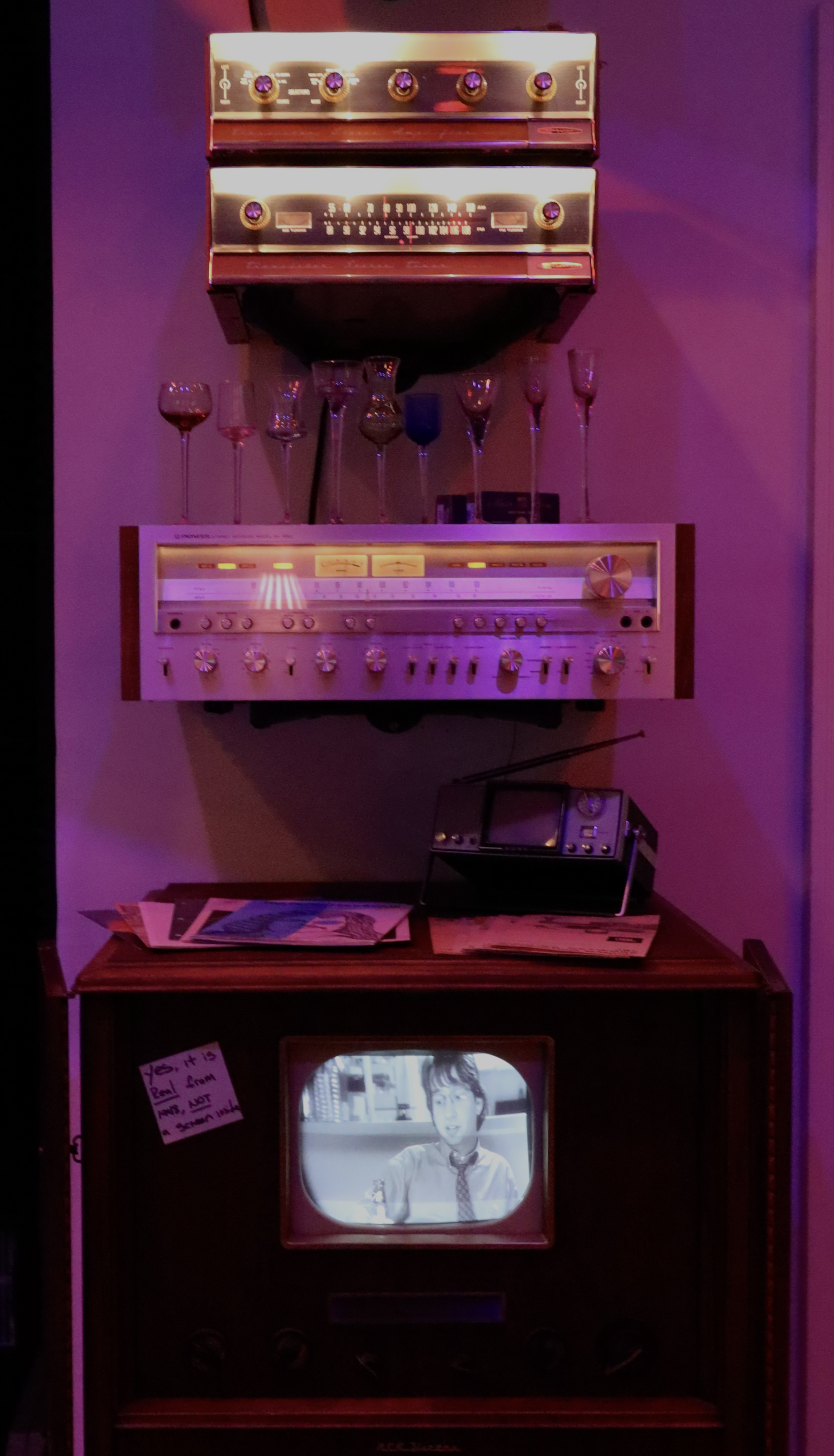

That’s Kaspar Yardley, the owner of Stereo Rehab, a restoration service for collectible and vintage audio equipment located on Western. Don’t try and look for some chichi storefront, though, because it’s after you walk through the blacked-out glass windows that face the sidewalk that you enter a room set up as a living room. It’s a dark room illuminated by pink hues, full of lit candles, vintage audio equipment, a couch, numerous tables and various knick-knacks that feature everyone’s favorite friendly ghost.

KY: “There’s a lot of customers when they come in, I ask them, why did you buy this piece of equipment? And they all, almost invariably when I was a kid, my uncle had it. When I was a kid, my dad had, so it’s human nature to want to kind of relive your past. It’s a kind of a comfort food thing, if you will. So a lot of times people will buy equipment now they have the means. You know, they’re grown up and now they can afford to buy this stuff that they coveted when they were a little boy and they looked up to, like, this thing sitting to our right, this receiver from ‘64. Um, people want it because they can buy it now and they want to kind of relive their past is the bottom line.”

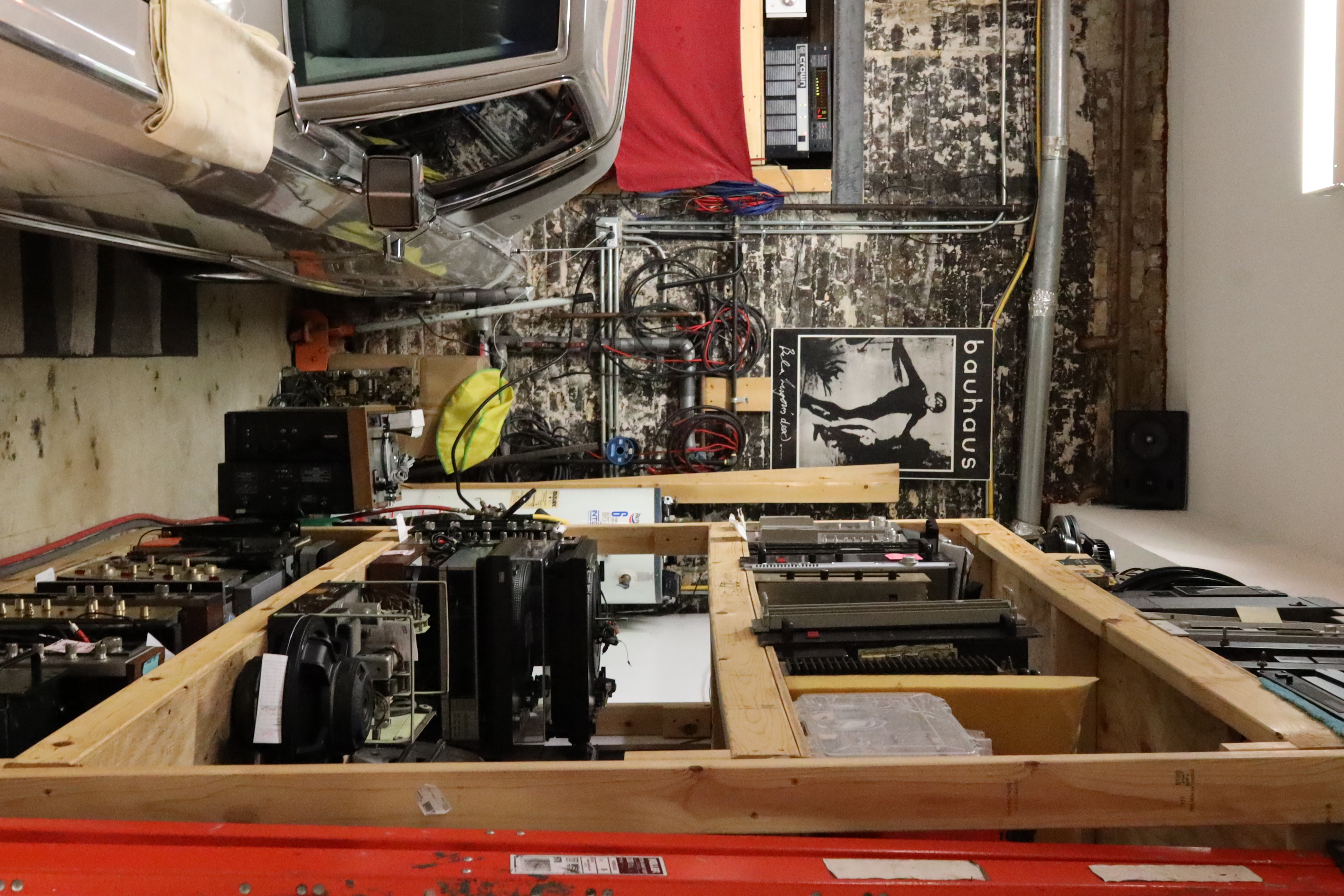

The phrase “once a good design, always a good design” itself can be argued that it’s becoming absolute with time. I mean, after all, an item that has a limited warranty isn’t ever gonna pride itself on being long lasting. Take a turntable that was made during a time when vinyl was still the primary medium for audio. When it wasn’t just companies that knew the value of speed consistency, control of the stylus in the groove and mechanical isolation. Unlike the trendiness of quote-unquote vintage vinyl today, well-made turntables weren’t just about seeing a machine that has something touching a spinning disc.

KY: “That turntable will be something that you can pass down to your kid and it will still be working with normal maintenance, belt, bearings, drying up, stylus and everything wearing out, which is normal versus something that’s designed to meet the expectations in the moment. But when it fails, they want you to throw it away and buy a new one. It’s not designed to be serviced. And the companies oftentimes won’t even warranty. They won’t stand behind the unit after the warranty expires. It’s designed to fail after that and then they don’t care. There’s no support. And it’s not economically feasible to service it because it’s not meant to be serviced.”

Since we’re talking about the essence of time, I’ll take this moment to introduce Simon Epelman, a watchmaker and repair specialist who has been practicing the craft for nearly 40 years. His shop is in the Mallers Building on Jewelers Row in the Loop. It’s one of those Chicago architectural gems — pun intended — that transport you back in time to the 1920s with Art Deco detailing lining the walls and faint cigarette smoke wafting through the hallways, peeking into storefronts.

Simon Epelman: “I like old stuff. Old stuff was made much, much better. And some people have the same watch, like, for 20, 30 years. And, uh, if I can fix it and [a] person’s gonna enjoy to wear the watch, I’ll do it. And they happy when it’s ticking, especially if it’s a sentimental value left from [a] grandfather, grandmother, or father. And that’s, that’s when I have a satisfaction, when they happy.”

KY: “It’s rewarding and quite frankly, no b——t, when you see a customer sit down and listen to their equipment, it’s an experience because not only are they listening to music, but you’re actually watching them kind of go back in time.”

KY: “It’s something that’s imparted to you from a family member or somebody in your family who did it and it’s, it’s like the old world. It’s like a baker, you know. You know, I’m gonna teach you how to take this: You’re gonna take this cup, you know, whatever, but it’s something you have to pass along and that is deemed as being unnecessary and irrelevant in today’s culture and the elders, though I love– when I was a little boy I used to hang out with older people and, and that’s how you learn s—t. If you surround yourself with a bunch of idiots, you’re all going to be in the same field. You must concede and surround yourself with people that are smarter than you, that have something to offer because it’s the only way you can elevate yourself.”

There’s something about the wealth of knowledge that these kinds of crafts and art forms have the ability to impart on people. It’s not the actual need of learning about the intricacies of audio equipment repair or watchmaking but rather about the fact of appreciation. Finding the time to place yourself within the role of not only a consumer but as someone actively living out a story, might just be a small aid that can be employed in our rapidly changing world. For Kaspar Yardley, that story started by hanging around TV and audio repair shops as a kid and learning skills from their owners. For Simon Epelman, after emigrating from Russia and before moving into his current storefront in 1985, he learned from his uncle through a year-long apprenticeship.

SE: “To be a qualified jeweler or watch repairman, you need to study. You need not, not only practice, you need a theory. So, it’s very hard to find really good jeweler or really good watchmaker. So, and that’s unfortunately every year gonna be less and less.”

SE:“I have so many times [a] customer call and say, I have a watch from my father, my grandfather, and it’s [an] old mechanical watch. And I ask, uh, few people and nobody can fix it. I always say, listen, I don’t want to promise you by phone, but if you come, if I can fix it, I can fix it. Uh, very rarely, very rarely, I say, ‘customer, it’s time to get new watch.’ But otherwise, you know, I was lucky enough, you know, in the mid ‘80s, uh, uh, we was buying old equipment, old watches, old parts, old movements, so right now I kind of fix, I can fix everything.”

KY: “They have a finite lifespan and there will come a point where those parts are no longer available, and that’s going to be a problem. I’ll be dead by then. So, I’m not worried about it. But, like, mechanical things like this, that doesn’t wear out. It’s parts that are actually working that are what would eventually wear out. And there’s going to come a point, like I said, where you’re going to have a hard time getting things that are correct and proper. Then you’re going to invite people doing jerry rigging and improvising, and then you’re going to open the door to failures because it’s not operating the way it’s designed to operate.”

SE: “30 years ago, you can see people wearing bracelet, rings, chains. Man was wearing the chains and bracelet. Right now, you cannot see man wearing the chain. It’s very, very rarely. It’s just because everything changed for our kids, for a younger generation, jewelry and watches kind of obsolete because, uh, they have a Apple phone. They have a Apple watch, they have a time on a phone, and jewelry, they kind of not on, uh, on their mind. All the gimmicks, all this technology stuff, yes, they are. But, uh, jewelry is dying.”

Perhaps it might be a way to understand yourself better or rather it’s simply the idea of supporting a craft; these tactile experiences are key in preserving identities and history — especially now, before it’s too late.

Header by Jana Simovic

NO COMMENT