Gaby Kuhn’s journey to find meaning through balancing motherhood and hustle.

Gaby Kuhn was sitting beneath the drapes of her 1898 Chicago apartment. The lace inner curtains remained drawn, allowing daylight to enter while offering her a view of the blurred city. Her newly born baby girl, Mina, was nestled in her arms when the phone suddenly rang. Upon answering, Gaby was asked to handle the wardrobe for Michael Jordan’s new McDonald’s commercial. Gaby was still nursing, but she was partial to her work and figured it would be a quick job.

“Michael Jordan was just making it, you know, he was being talked about,” Gaby said. “And I thought, ‘Oh, that’s okay, let me try that.’” So, she went, leaving her mother to take care of Mina.

Jordan brought a duffel bag of his own clothes, which made Gaby’s job quick, and she did not have to stay all day. But after a few hours, she felt an all-consuming panic: “Oh my goodness, I have to feed her.” Despite finishing the job, she promised herself she would not leave Mina’s side for a while after that.

“After I got home, I thought, I can’t do this. I just can’t do this. I don’t want these kids growing up like somebody else,” she said. She could work later.

“It’s okay, you can stay at home if you want to,” her husband told her. “We can make it.”

In 1954, before Gaby had been born, her mother, father and older sister moved from Germany to Detroit – with hopes of living a comfortable life in America. Gaby lived a rather traditional childhood as she learned from her grandmother, who was a midwife, and her mother, who stayed at home to raise Gaby and her sister. So, from a very young age, Gaby learned how to do it all, from sewing to cooking to yard work.

“My mom can do everything, so we were brought up doing everything from my mom’s side and all those sports and things from my dad’s side … and the art actually from my dad, but my mom was very clever,” she said.

Her father, John, worked as a sculptor and painter, primarily doing religious statues for churches; this helped him land his job doing clay modeling at General Motors Design Studios for 40 years. He was also really into gliders – those engineless planes with only one seat but a wingspan of about 40 feet – and built them in the garage. He eventually made it into the Soaring Hall of Fame with his competition number being 32.

Gaby remembers her father coming home after he was out flying. He would pull in the driveway with the glider sitting in an open bed trailer and have Gaby and her friend sit on the back of the trailer while he pulled the glider up the driveway to put some weight on it, so the tongue wasn’t too heavy for him.

“And that was special,” she said. “I think dads kind of do that to make you feel like you’re helping.” And many years later, she did the same with her three girls.

With hopes of a new beginning in a grander city, Gaby moved away from her home in Detroit after high school and settled in Chicago in 1975, when she was 18 years old. She had four interviews in one day. First, she visited Saks Fifth Avenue to apply for a job designing their display windows, which went smoothly. She then had two more successful interviews before attending one at an accounting office.

In the office, Gaby’s decorated hands were folded on the desk of the hiring representative, who sat in front of a floor-to-ceiling glass window within the clouds of the Windy City. After a seemingly successful interview, the hiring woman complimented Gaby’s rings and Gaby proudly told her that she had made them. The woman fixed her gaze on Gaby, her expression suggesting a mix of concern and sincerity, and told her, “I don’t think you’d be happy here because you seem like you’re very creative.” Her concern quickly gave way to enthusiasm as she proceeded to tell Gaby about a friend who was a writer over at Leo Burnett, suggesting she should go there to interview instead.

On that day, Gaby got all four job offers, but the words of the hiring woman lingered with her. Consequently, she turned down all four offers and set her sights on working for Leo Burnett. She got that job, too, and spent five years in TV production at the company. She was now much more acquainted with the city and got to know many of the directors and producers in town. Every Friday, her colleagues would meet at a bar for disco night, and little did she know, her future husband, Chuck, was a part of the group.

As Gaby and Chuck – who kept running into each other at the Prudential Plaza Bank – began going on movie dates here and there, their bond grew stronger. However, Gaby had already decided to spend the year of 1980 in Germany to be with family. She left her job at Leo Burnett, packed a suitcase and worked at her uncle’s Toyota dealership repair shop while also fixing up an old Goggomobil – a two-seater microcar that was first developed in the late 1950s in Dingolfing, Germany.

Towards the end of her stay, a letter arrived at her uncle’s house from a friend back in Chicago. All within Gaby’s one year abroad, Chuck had dated a girl for six months and was married to her by the end of the year. With this news, Gaby figured that the potential of a love affair with Chuck was over.

Now, things were changing. “You’re at a point in your life and you think, ‘Where am I going,’” she said. So, her grandmother baked her a man made of flour instead, hoping it would ease Gaby’s worries about finding a human one just for a little while. She kneaded the dough, carved out a few men from the soggy yeast and slid them into the oven. And then they ate them. “That put us in charge,” Gaby said.

In 1981, Gaby returned from Germany as a single woman. It was then that she ran into Chuck at the bank once again. He told her he had gotten a divorce, and they picked up right where they left off; more movie dates, more dinners and an escalating enamorment with one another.

“Things come later in life,” she said. “It will get there and just don’t be discouraged.”

Her connections from Leo Burnett helped put her on the radar and her heart was now set on becoming a stylist. It seemed like the perfect fit for Gaby to be involved in wardrobe, the sets and props and maybe even makeup for talent. “That was me,” she said, raising her voice. “Please just hire me, just hire me once,” she said even louder.

She recalls once building a pair of high heels out of bread dough, except she couldn’t use real bread because the set lights would have ruined it. Instead, she made them out of a salt dough recipe that resembled bread. She then brushed and glazed the heels with an egg wash, perfectly replicating the appearance of real bread. Her innovative approach reflected her commitment to excellence in her craft, as always.

“If you’re good at what you do, then people will find you,” she said.

Her dedication didn’t just stop with work. In 1985, Gaby and Chuck finally got married, and in 1986, they had their first girl, Mina. After only a few more years, two more baby girls were lying beneath the bay windows.

“Five years brings a whole lot,” Gaby said. “Without even knowing it was going to happen, I got married and had three kids … it was all in five years and I didn’t even foresee that was going to come and then that goes by fast.”

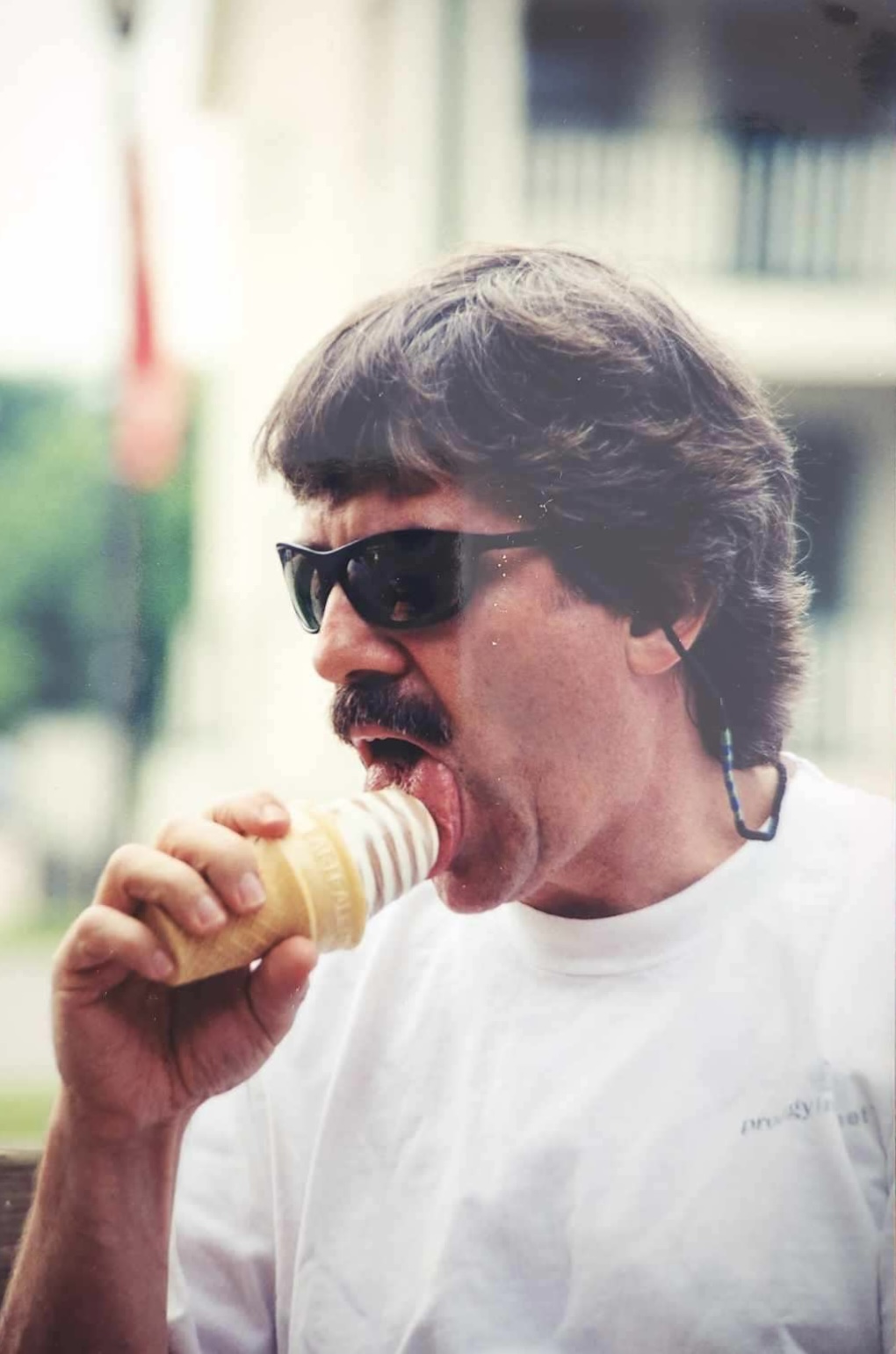

- Gaby (left), 46 and Chuck (right), 55 eating ice cream.

- Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

Gaby made the decision to stay home and raise the children. Chuck reassured her, promising that all the bills would be paid, as he was now working as a financial planner. Before getting married, Gaby had only ever worked to pay the bills. All she wanted to do after high school graduation was work; she skipped college and all the drinking and partying. It just wasn’t her style, but she always had the drive to work.

“I never once thought that I’d be a stay-at-home mom,” Gaby said. “I don’t think I ever thought not to ever have them with me.”

It was a relief to no longer feel burdened, now able to stay at home and raise her girls, which is something she felt essential. Gaby understood that her hustler’s mindset must be put to rest, at least for a little bit.

“I thought, I can make things for people at home and then deliver them,” Gaby said. “Just change the direction a little bit but stay in the industry.”

In 1989, Mina was three and Amanda was one. Amid the diapers and tantrums, Gaby received a call from her old assistant, Aimee, who did not have children and was now a prop master. She asked if Gaby could make 42 palatial gold bows for the set of Home Alone. But Gaby could not find any ribbon quite wide enough, until she found a certain crinkled roll. If you stretched and stretched and stretched the ribbon, it would become straight and suitably wide enough to create an impressive bow.

“Now, this is what makes it so exciting, when somebody comes to you and says this is what they need, and it is not available, that you can deliver … and she called me and my girls,” Gaby said. “It did feel good to get a call to do something from someone who knew what you could do.”

The only way she could do any work was by including the kids, so her two girls, enamored by the crinkled noises that filled their ears, assisted Gaby in her creations and began to stretch the ribbon themselves.

“For the girls it was fun, you know, they’d open up this crinkly ribbon … and it made a lot of noise when you did it … and then I’d run it down the house and tape all those things together till I got it big and then I would construct these huge bows with the tails,” she said.

After a few afternoons of stretching, knotting and hanging the ribbons, Gaby’s entire house was sprung with gold. When she was done, she put each bow on a piece of furniture and then the next one on another piece of furniture. Her house was hidden beneath all the bows.

7/42 gold bows for “Home Alone.” Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

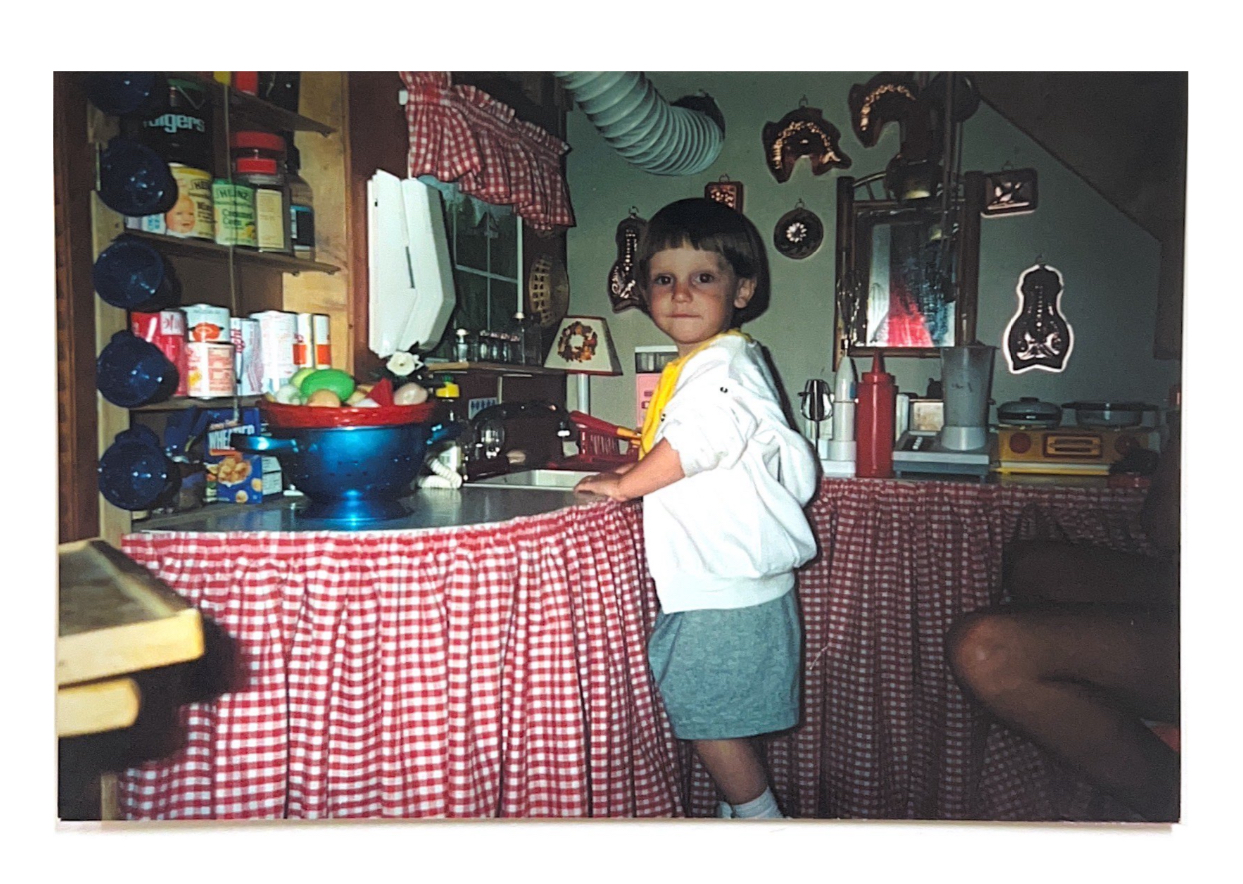

“Everything was a craft at our house,” Gaby’s eldest daughter Mina recalled as she reminisced over the play kitchen Gaby crafted for her underneath the basement staircase.

This kitchen was not merely one of those little plastic playhouse kitchens – everything was real. Red and white gingham fabric spread across the countertops, with a toaster oven mounted into the wall so it would open like an oven. A painting of a landscape with trim surrounding it acted as a window, just like how a backyard would look. There was a steel sink and a real faucet, but no running water. Cans of soup and boxes of cereal lay atop the beams of the wall. It truly was a real kitchen, and Gaby had thrifted it all.

“Her crafts could be anything from sewing to building something with power tools, which feels much more than a craft,” Mina said.

A friend in the little kitchen underneath the staircase. Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

The little space beneath the staircase not only housed this lavish kitchen but also acted as a hub for Mina, Amanda and Coco to explore other careers. There was a hospital bed with dolls and stethoscopes and a desk with office supplies where Gaby and Chuck’s nameplates from Leo Burnett sat. Gaby felt it was necessary to show her girls that women have many career options beyond solely being a mother.

“I can’t say that I missed work,” Gaby said. “I don’t think I had a longing.”

Mina’s Halloween costume Gaby had made from a thrifted dress. Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

And so, Gaby figured out other ways to channel her craftiness. For Halloween one year, she made a costume from a gold dress she had thrifted, cutting it up and sewing it so it would fit a four-year-old.

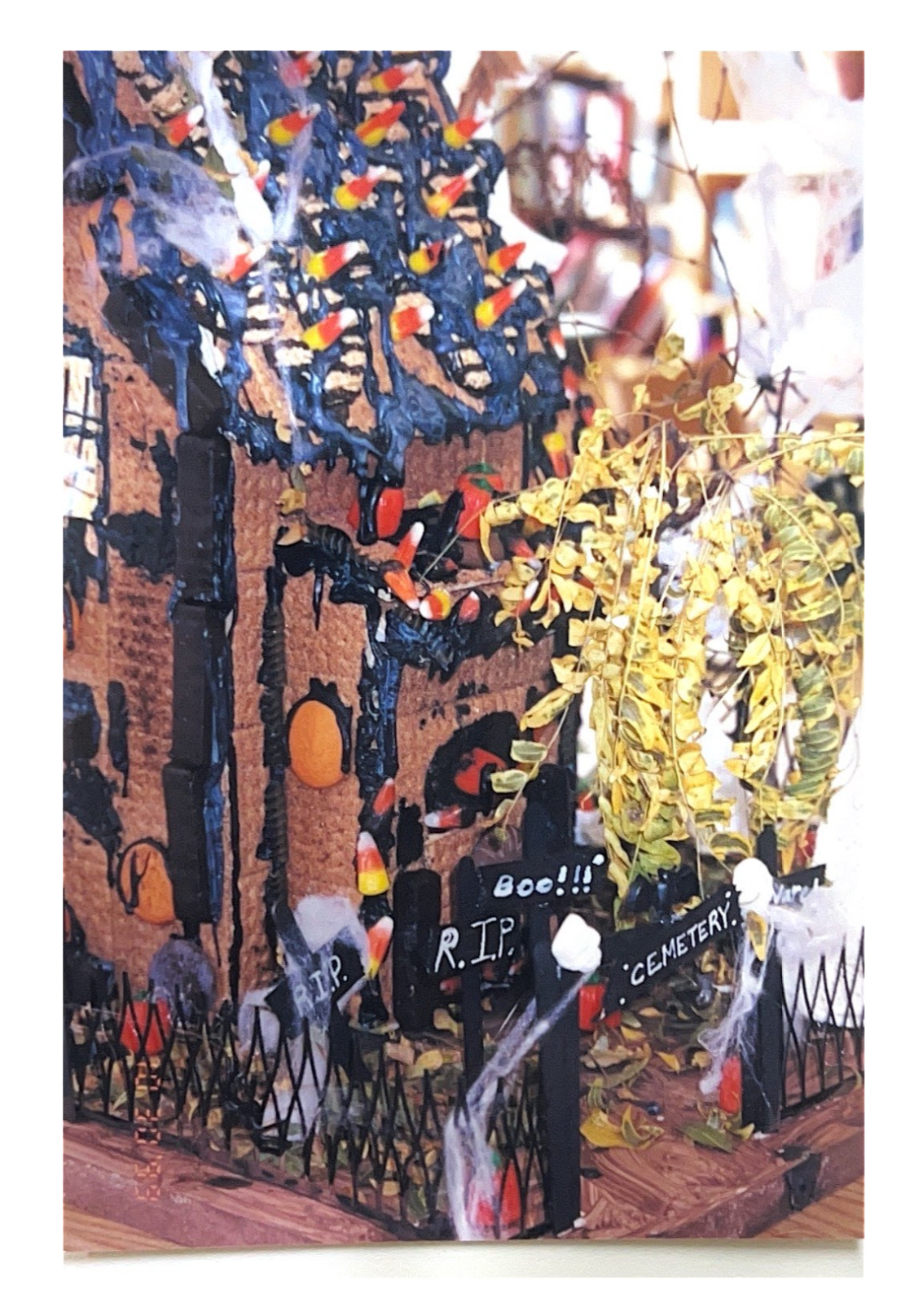

Every Halloween, Gaby and her daughters would build a haunted house made of graham crackers. They would take green strawberry cartons and spray-paint them black to act as a fence around the house. Deep purple and black superglue dripped down each corner, and the roof was consumed by striped candy corn. Sometimes they would even take the dead bushes from the front yard and use them as trees. Now, Mina carries on the tradition by making a graham cracker haunted house with her own children every year.

Graham cracker haunted house. Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

As her girls grew older and began schooling at the Latin School of Chicago in 1996, Gaby started teaching crafts and sewing twice a week to the first through fifth graders; she also spent much of her time making costumes for the theater productions.

“You can be the fly on the wall as your kids are growing up, you know exactly what’s going on and who is doing what,” she said.

Gaby found that she could be more involved with the school and in her daughters’ lives this way. All the kids knew her as Mina, Amanda and Coco’s mom, and her girls liked that.

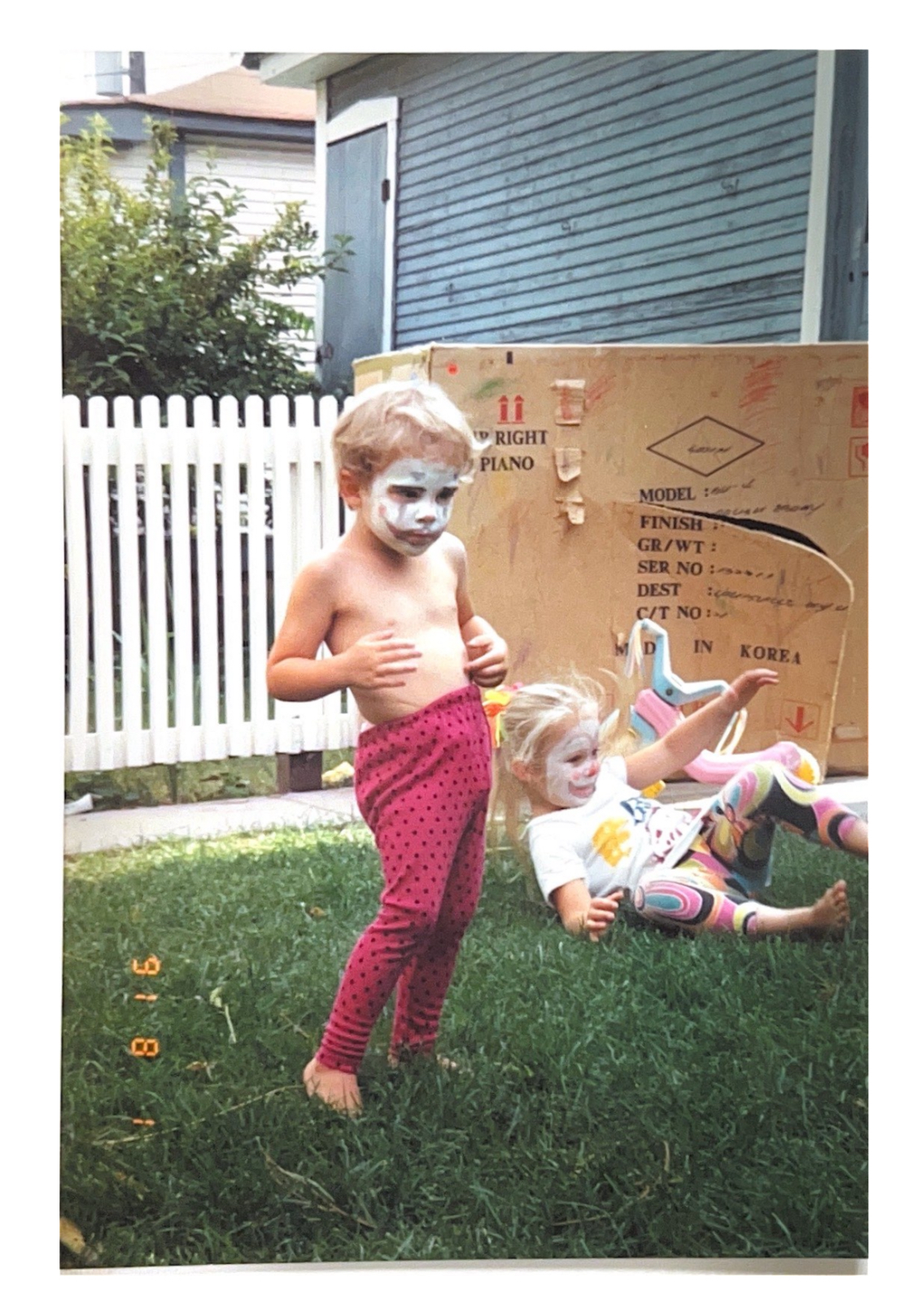

“We always had friends over dressing up and doing creative activities because of all the amazing things she had at our fingertips to spark our imagination,” Mina said.

Amanda (front) and Mina (back) playing in the backyard. Gaby had painted their faces. Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

Oftentimes, Gaby would plant and pot in her garden while Mina, Amanda and Coco frolicked around in the backyard with the neighbors. And then they would all run over to Gaby, panting in exhaustion, ready to absorb her gardening wisdom.

“The whole neighborhood kids could be included in the learning process of plants and flowers and rocks and bugs, and then I still got something done … because I didn’t always like sitting on the step chatting, which seems like unbelievable,” Gaby said.

She always found a way to include her girls, in whatever it was she did.

In 2000, increasingly more movies were being filmed in Chicago, and Gaby got a call from Aimee to work on Return to Me. She only worked on set for three weeks, but of course, Amanda, Mina and her friend were all extras in the movie.

Being Mary Jane in 2012 was Gaby’s first major project since the girls were born, and it required her to be in Atlanta for three months at a time. With Mina and Coco moved out, and Amanda, 20, still living at home, Gaby felt comfortable entrusting her to look after Chuck. While working on set, Gaby traveled to Atlanta for a few months to work on a season, then returned home for a month. After getting back in her groove, if Aimee called, no matter where, Gaby would go. Everyone was rooting for her.

By 2017, Gaby stumbled upon a charming storefront available for rent in a tucked-away corner of a Lakeview neighborhood. With longstanding dreams of owning her own shop, Gaby saw this as the perfect opportunity to bring Studio 32 to fruition. She found that many people wished to learn skills like sewing and knitting, which they hadn’t been taught by their parents, just like she had. So, Gaby taught classes and rented out the store as a maker’s space for those who needed a place to work but lacked the room at home. Just a couple of years later, she was forced to close Studio 32 during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, once 2021 came around, Gaby was eager to reopen as something new.

“I would like to take all the stuff that I have accumulated, or that I’ve fixed, you know I have it all stored at home, or that I collected … and just open up to a thrift store. That’s how Studio 32 Thrift Store was born,” she said.

But, Studio 32 coined its original name in 1995 when Gaby was making props. Chuck, being a financial guy, insisted Gaby needed to incorporate the name for invoicing purposes. Since 32 was her father’s competition number, it became Studio 32.

Gaby’s Chevy Astro, with a taped ‘32’ on the back window. Photo courtesy of Gaby Kuhn.

Now, Gaby spends her days sourcing new inventory for Studio 32, making old things new again, and of course, with her grandchildren. She hopes for a larger space next, but it’s challenging to part ways with the place she has fashioned so intentionally. Each little room brings the shopper a new feeling or vision, with nothing cluttered or stuffed to overwhelm their imagination. Soft lighting from lampshades casts a gentle glow in every corner, and a finger never touches the switch to turn on the harsh ceiling lights. Within her space, there is purpose with every detail.

Amid her daily endeavors at Studio 32, Gaby is the epitome of gratitude and pride for the life she has made and the place she is in. She especially gleams knowing she has Chuck and her three girls beside her. But every now and then, she is pierced with the words her father’s good friend once told her.

“He had said, ‘If your father would have stayed here and never had a family, he would be a famous artist,’” Gaby whispered, her voice quivering. “I don’t think he ever thought, ‘Oh, if I just didn’t have these kids, that I could be somebody.’”

Gaby knew that her father did precisely what he wanted, much like she did with her own family. It wasn’t a matter of choosing one over the other; she never had to decide whether she should attain her dreams or leave it all behind to become a mother. And neither did her father.

“I always found a way to do both … sure, you might put things on the back burner, but if it’s something you really want, that all comes back,” she said. “And we are all somebody, just like he was.”

As we sat behind the desk of Studio 32, enveloped by the yellow glow of the lampshades, a sudden, sharp knock on the door halted our conversation. Gaby wiped away the tears beneath her eyes and opened the door to a comforting presence. It was Chuck.

“What are you guys doing? I thought you would be home at 10:30,” he said, casting a glance in my direction. “What are you talking about?”

“Oh, yes, just talking about dad,” Gaby replied.

Chuck smiled at her, a half-smile that lifted only the right side of his mouth, then pulled her into a warm embrace. “It’s going to be okay,” he assured her.

Gaby returned to her seat opposite of me, her eyes meeting mine. “See, it all works out,” she said softly.

Header by Julia Hester

NO COMMENT