“Working in a law library inside is really the closest most prisoners will get to having a lawyer help them.”

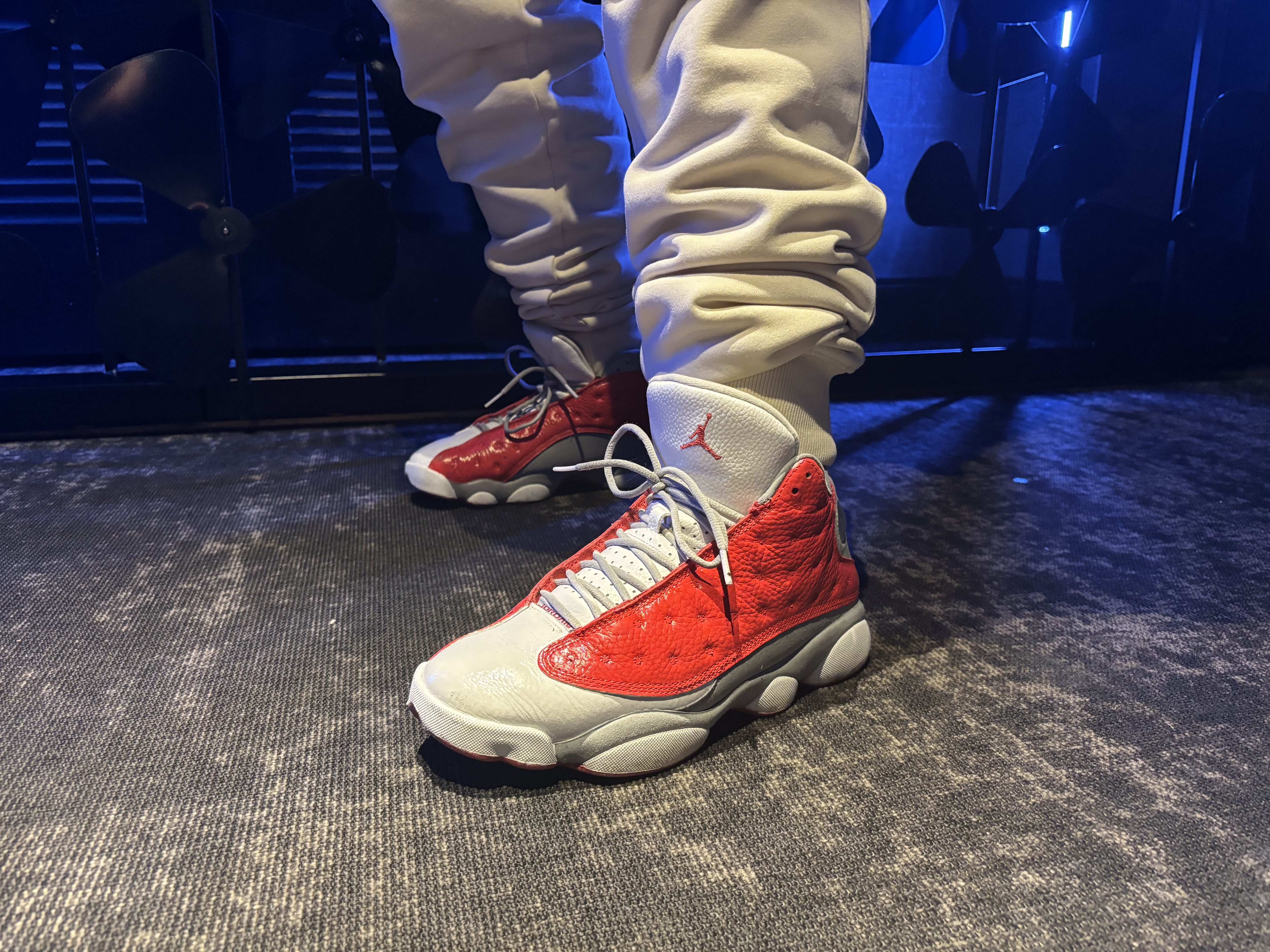

James Lenoir customizes shoes.

“I’m a strong believer in presence,” said Lenoir. “Like, make your presence known….know it’s a world to be known by somebody.”

He gets lost in the process, listening to music and painting bright speckled patterns on white sneakers.

It’s one of Lenoir’s many remarkable abilities, and one that he picked up while in prison.

Lenoir was incarcerated at 18 years old in 2003 and did time in various Illinois Department of Corrections facilities. He began working at the law library.

From there, he began his paralegal certification, which he later completed at Stateville Correctional Center. Paralegals are legal specialists who typically work under the supervision of a lawyer, researching cases and drafting briefs.

For many people in Lenoir’s situation, being in a position where he could learn the law was not just a source of empowerment, but a necessity.

From our few meetings, it’s clear he takes his appearance and presence seriously. He often sports similarly bright white sneakers alongside a snapback hat and a friendly grin.

“I told my judge at the time of the motion that I’m fighting for my life and I want to know what’s going on,” Lenoir said. “I can’t get an understanding of the law once every three weeks,” which was how often he was able to speak with his lawyer while incarcerated.

Photo courtesy of James Lenoir

Through his work and studies on the inside, however, he was able to eventually obtain an associate degree, along with valuable life advice.

While incarcerated, James Lenoir met a man named Brian Beals, who became his mentor.

“Count on yourself to get you out, by teaching your lawyer what you need them to do to get you out,” Beals told Lenoir. This inspired Lenoir to start thinking differently about his situation.

Lenoir’s role as a paralegal on the inside meant he was able to give legal advice to his fellow prisoners, according to Alan Mills, executive director of the Uptown People’s Law Center.

“Working in a law library inside is really the closest most prisoners will get to having a lawyer help them,” said Mills.

Lenoir’s situation is not unique, either. Anthony Jones, another returning citizen who now works with the Illinois Prison Project, found a similar sense of agency from working in the law library while incarcerated.

Jones found that meaningful work, like that of a paralegal, is a good way for those in the system to push back against what he calls the “sheep mentality” that pervades newly incarcerated people.

Lenoir’s work and eventual degree gave him power in a system that offers very little in the way of genuine rehabilitation. But he struggled to find a similar role in the outside world.

Lenoir grew up in the affordable housing project St. Stephens on the West Side. He was the youngest of six siblings, who all had a close relationship.

After he was out, Lenoir’s family struggled at first to understand how he had grown and changed on the inside.

“A lot of family and friends didn’t know the knowledge, the models I was building and gaining,” said Lenoir. “I was trying to share it, but they was disregarding it as if it was jail talk.”

Being incarcerated for 20 years has meant that Lenoir wasn’t able to keep up with changes in technology or make industry connections, the types of things that make a difference for someone pursuing a career in law.

“I had to learn how to use an email or PDF file,” said Lenoir. “someone had to teach me these things … you can’t expect everybody to just come out and rebalance their lives to the lifestyle that everyone else is living.”

In addition, law firms typically don’t allow paralegals to give advice on the cases in the same way they do on the inside, said Mills. And many law firms are hesitant to hire those who were previously incarcerated.

“I think in general, people who are jailhouse lawyers, particularly good jailhouse lawyers, are pretty frustrated when they come out, at the limitations that they find on what they can do,” said Mills, using a term to refer to incarcerated people who give legal advice.

However, Lenoir has been able to volunteer with Parole Illinois, an organization working to reinstate parole in the state and take speaking engagements, though they don’t always pay well.

Between all these obstacles, Lenoir has tried to maintain that same drive that drove him to become a paralegal in the first place: that desire to help himself and others improve their situation.

“The next person, I can tell them some of the hurdles that’s going to come up, and I can tell them some of the pain that’s going to come up,” said Lenoir.

Header by Julia Hester

NO COMMENT