Many of us choose nicknames for fun. Some of us choose them for survival. Kwok Ging Huie — also known as Shu H. Ng, Gary Huie Shu and my great-grandfather — made a life for himself in America through aliases. Such a life is that of a paper son.

Paper sons were Chinese men who circumvented anti-Asian exclusion acts via fraudulent citizenship from 1882 to 1943. They assumed the identities of legal Chinese residents in America by purchasing their documentation from legal Chinese citizens or receiving it from relatives/friends from their village.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act limited the selection of those who could immigrate to the U.S. from China during the late 19th century to mid WWII. In fact, it was the first U.S. law to explicitly target a specific nationality and was passed to maintain “racial purity.” Those who could immigrate were merchants, students, teachers and diplomats. Paper sons did not fit those categories, so they were forced to bypass laws for a better life in America. Most entered through the immigration port Angel Island in San Francisco Bay.

“Some people [Chinese residents in America] might have had extra certificates,” said Soo Lon Moy, immediate past president of the Chinese American Museum in Chicago and co-editor of Chinese in Chicago: 1870 -1945. “They sold them to people from their village or people who were related to them. Sometimes, they would just give it to people who are part of their family and help them in the business they’re in.”

My great-grandfather as a child with his mother in Canton, now known as the Guangdong province in Hong Kong. He was born in the city of Shunde.

My great-grandfather obtained one of these certificates. He left his wife and child in Hong Kong and wouldn’t see them again for over 20 years. He assumed the identity of someone named Shu H. Ng and suppressed his real name, Kwok Ging Huie, underneath.

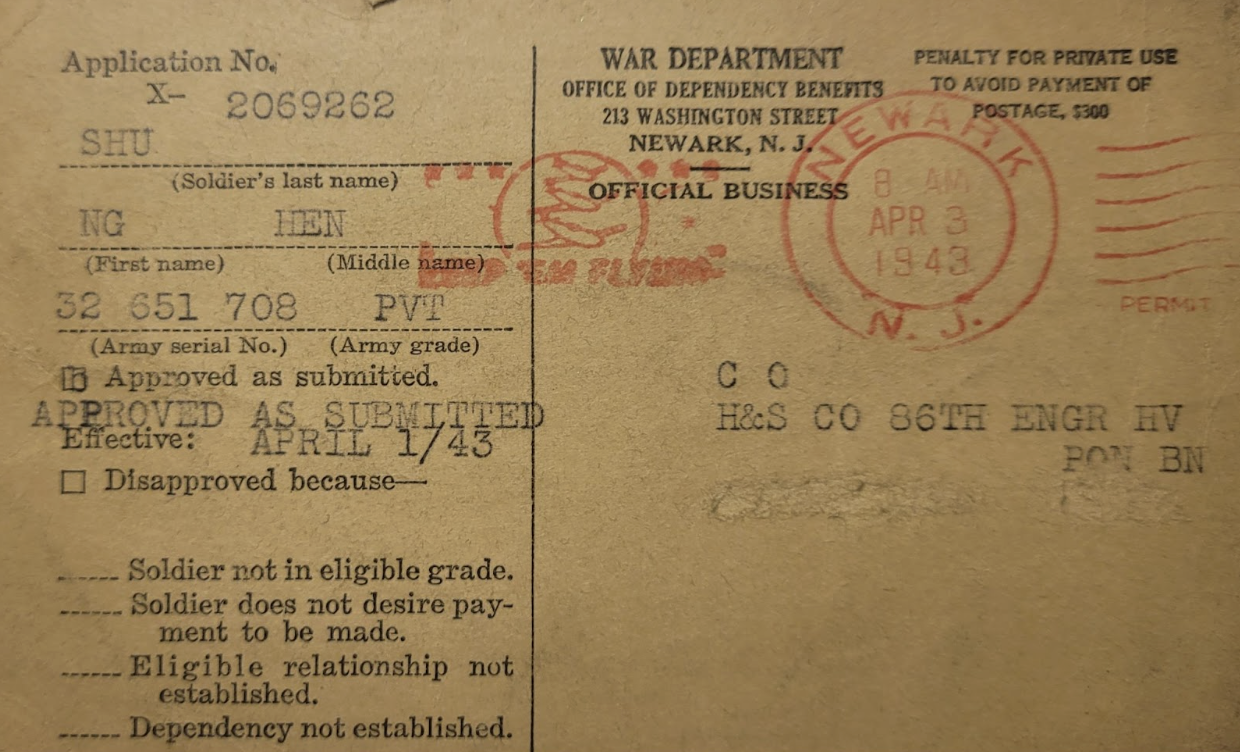

My great grandfather’s original benefits registration card during WWII. The card used his fake name, “Shu Hen Ng.”

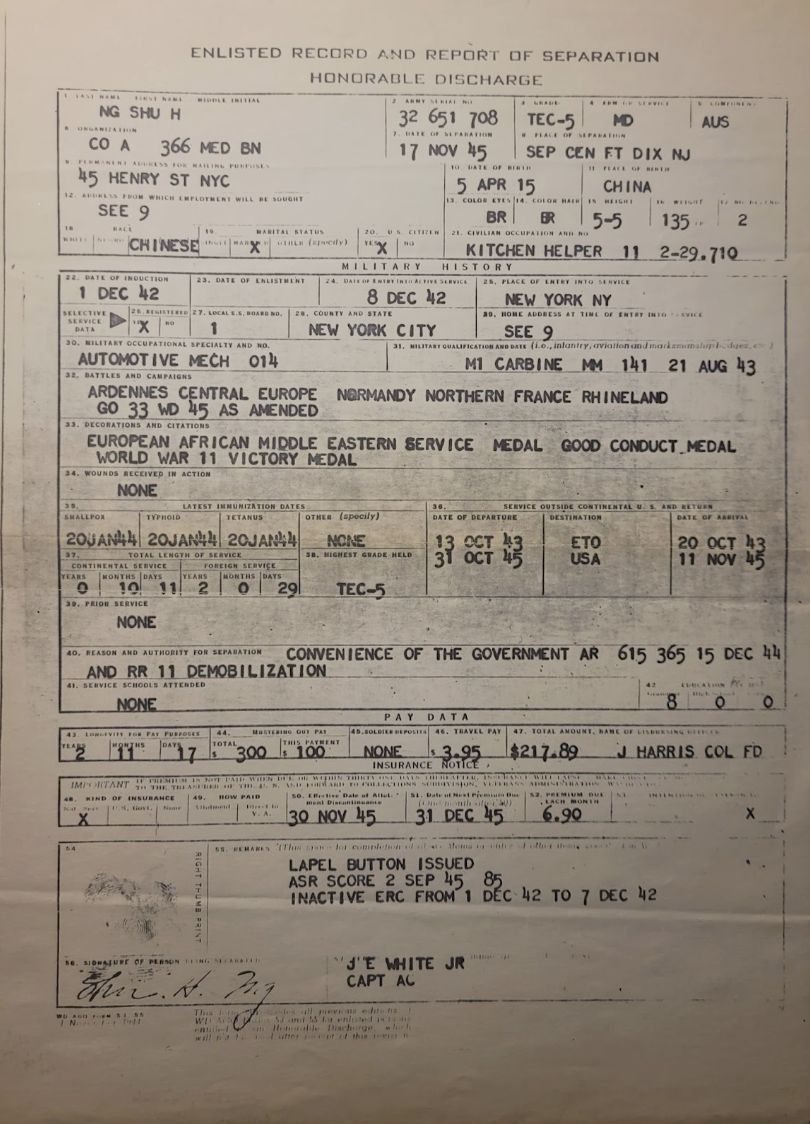

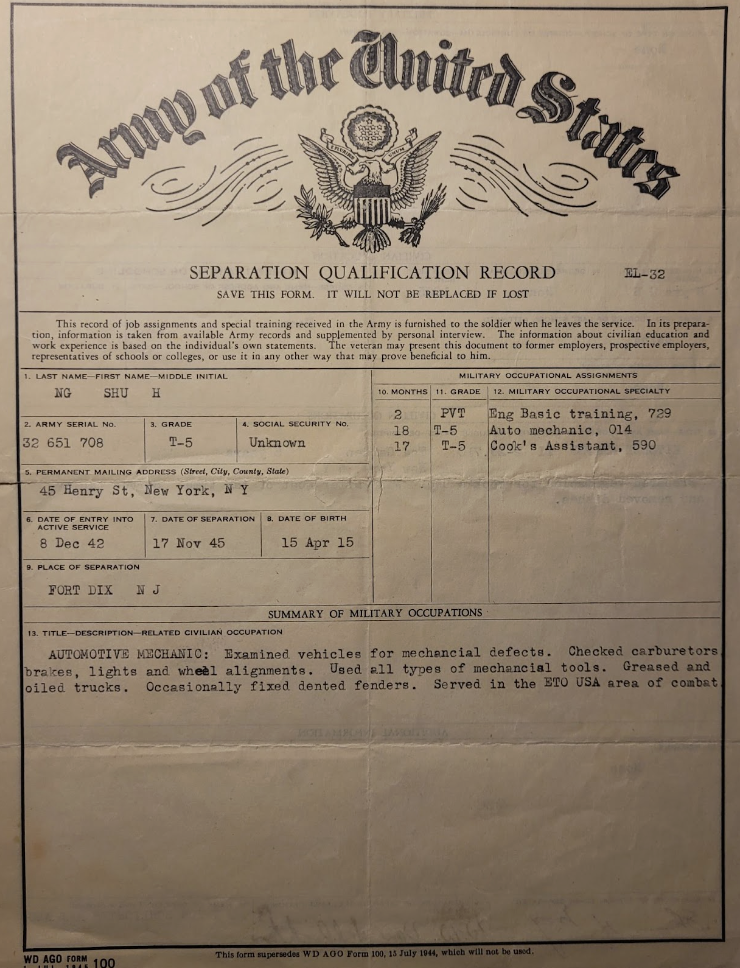

He worked in the laundry industry in New York City with the goal of earning enough money to bring back to his family in Hong Kong but ended up serving in WWII in Normandy, France. From 1942 to 1945, my great-grandfather was a tech corporal automotive mechanic, decorated with a European-African-Middle Eastern Service Medal, Good Conduct Medal and World War II Victory Medal.

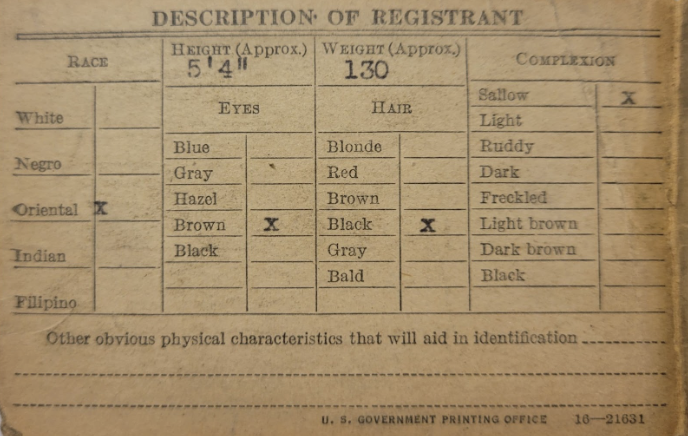

My great grandfather’s WWII benefits registration card, which lists his race as “oriental” and his skin as “sallow.” Indian and Filipino were considered separate racial categories at the time.

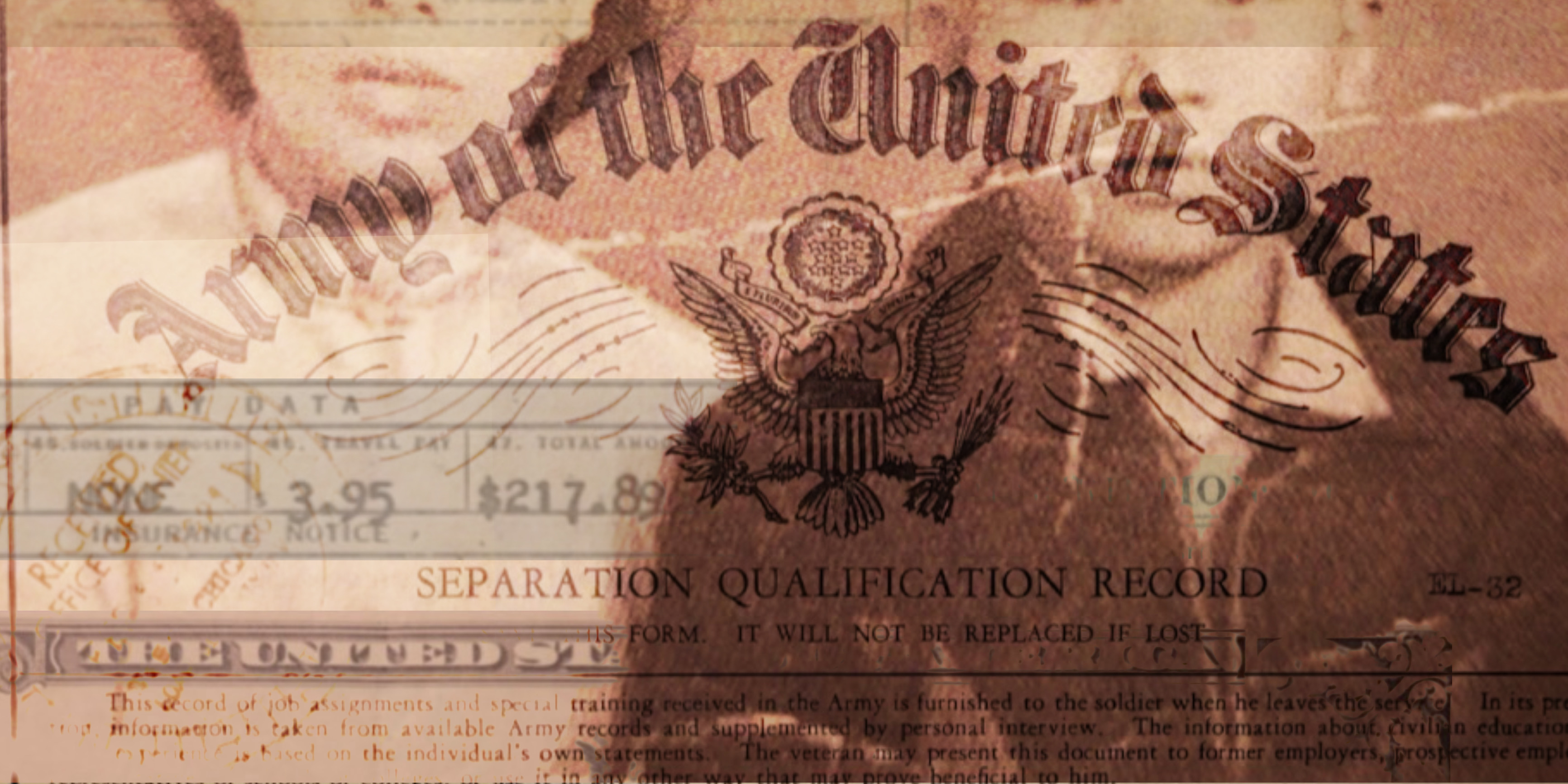

A copy of my great grandfather’s honorable discharge papers at the end of WWII. It lists his awards and lists his fake name, Shu H. Ng.

“There were so many men that went into the service,” Moy said. “They joined the Army because they really loved the United States even though they were treated so poorly. They still had a lot of loyalty.”

My great-grandfather’s separation qualification record for WWII, which describes his job duties as an automotive mechanic.

My great grandfather left WWII with honorable dedication to the U.S., but an ambiguous identity. His honorable discharge certificate is in the name of his paper son identity, and he would juggle this fake name with his real one until 1968.

After President John F. Kennedy’s proposed 1965 Immigration Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, border restrictions opened up to Chinese laborers and family members of current Chinese citizens in America.

“The act had what they called a ‘confession’ if you wanted to confess that you were a paper son,” Moy said. “If you wanted to establish your surname, you were able to do that.”

Many paper sons revealed their status as an illegal resident in exchange for naturalization.

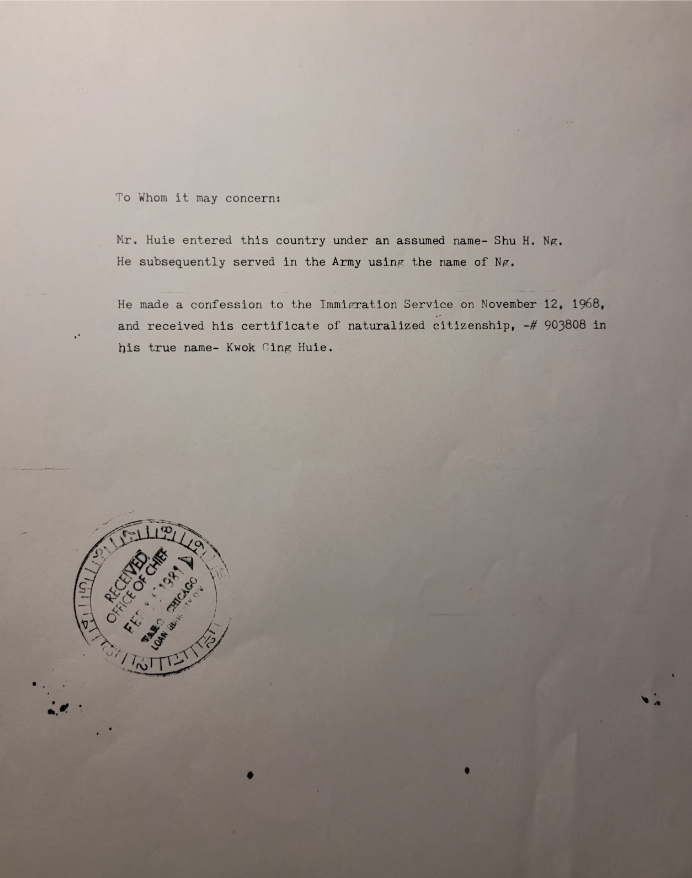

An unaddressed letter — presumably from the Immigration Service — to my family reads:

Mr. Huie entered this country under an assumed name- Shu H. Ng. He subsequently served in the Army using the name of Ng.

He made a confession to the Immigration Service on November 12, 1968, and received his certificate of naturalized citizenship… in his true name – Kwok Ging Huie.

A copy of the letter immigration services sent to my family regarding my great grandfather’s admission of illegal status.

After decades of living as another man under the risk of deportation, my great-grandfather finally reclaimed his identity. He brought his wife to America and reunited with my grandfather after over 20 years of no contact. His little boy was now a grown man with five daughters of his own.

My grandfather’s original, legal citizenship documentation. He was naturalized under his real name, Kwok Ging Huie, in 1968 after 20 years of living under a false identity.

Moy says the years fearing deportation have left scars on the few paper sons alive today.

“They don’t want to go through those memories,” Moy said. “It was very scary for paper sons when they first came … that’s why some are so secretive. Their wife didn’t know, even when they had kids. They didn’t tell them at all. Many of them took that to their grave with them.”

Despite the trauma that came with being a paper son, their legacy lives on through their descendants and “paper children.” Though Moy’s family were not paper sons, her grandfather sold his papers and welcomed a paper son into their family.

“He’s [the paper son] no longer alive, but his two sons … everytime they see me, we would laugh and say, ‘Here’s our paper cousin,’” Moy said.

As one of the most prominent families in Chicago’s Chinese circle, Moy also says her family were among the many that helped paper sons build community in Chicago. She still sees many of her “paper cousins” today because they are all part of the Moy Family Association, the largest family association in Chinatown.

“They [paper sons] were very loyal and had this feeling about giving back to the community,” she said. “They established not only associations, but they had Chinese schools for kids to maintain their culture.”

A portrait of my great-grandfather during his service in WWII.

Though he relinquished part of his identity for years and served a country that thought less of him, my great=grandfather always remembered where he came from.

My great grandfather (first row right) with his wife, my grandfather, grandmother and their six children, including my mother (bottom right)

Kwok Ging Huie was Shu H. Ng at one point in his life, but never lost who he was inside. He fought in the war, contributed to the legacy of paper sons and, most importantly, reclaimed his name for future generations of Huies to come.

Header by Anna Retzlaff

NO COMMENT