In the ‘80s, lesbian bars flourished all around the U.S. While only a fraction of those establishments still exist, they have an important purpose for the community they serve.

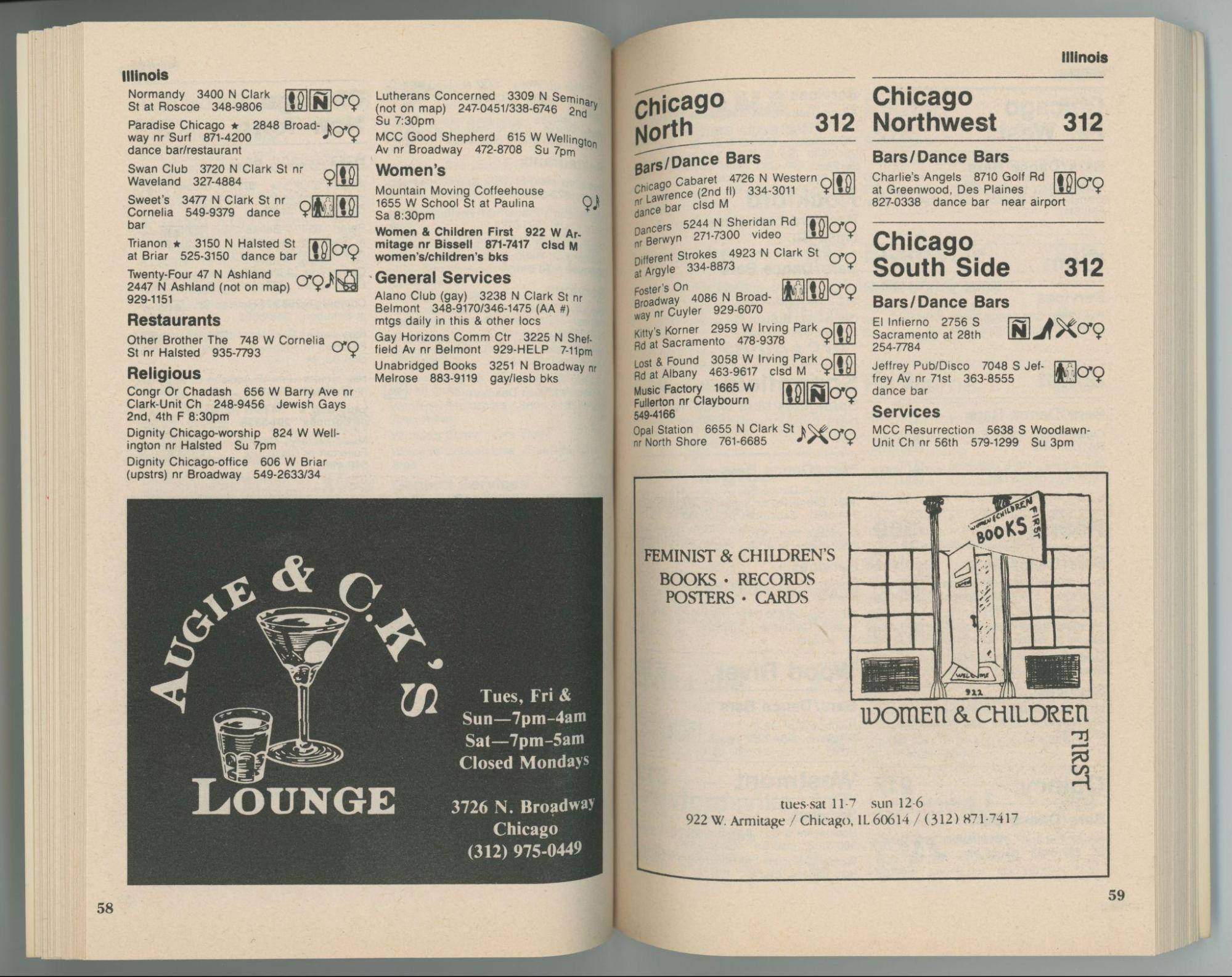

In the ‘80s, lesbian nightlife in Chicago was bustling. Every weekend, queer women gathered at Augie & C.K’s Lounge, The Ladybug, Swan Club or one of the many other lesbian bars dispersed throughout the city. But one by one, those spaces began to disappear.

According to the Lesbian Bar Project, there were once over 200 lesbian bars in the U.S. In 2024, that number has dwindled to a mere 33. Lesbians haven’t vanished. If anything, broader acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community has made it easier for queer women to realize their identities. So why have spaces dedicated to these women been mostly lost to history?

Jen Dentel, the community outreach and strategic partnerships manager for Chicago’s Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, has some theories.

“Because there’s more acceptance in the larger community, people go to spaces that are not just their own bars,” Dentel said. “But I think it’s more complicated than that.”

Dentel says that in past decades, lesbian bars existed as one of few safe spaces for queer women. But even then, there were risks involved with seeking out community. Gay and lesbian bars were often subject to raids, and those who did not escape the establishment at the time were arrested with their names printed in the newspaper the very next day as a way to shame those who dared to exist outside of the binary. Police used a section of the Chicago Municipal Code that banned cross-dressing — known informally as the “zipper ordinance” — to justify these arrests.

“It used to be that women’s jeans had buttons on the back, not the front,” Dentel said. “So, if you were wearing fly-front jeans, you could be arrested because they were men’s clothing.”

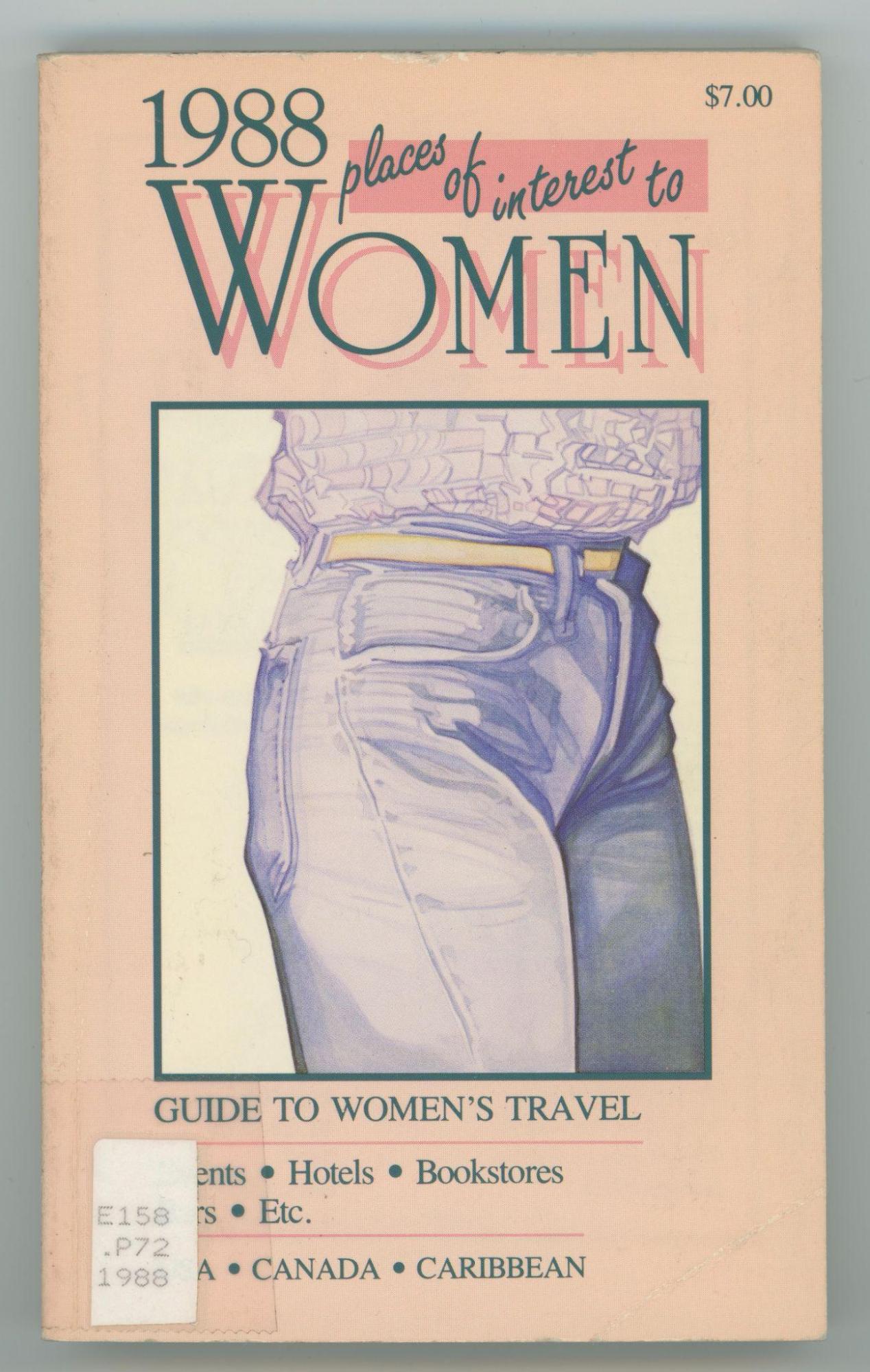

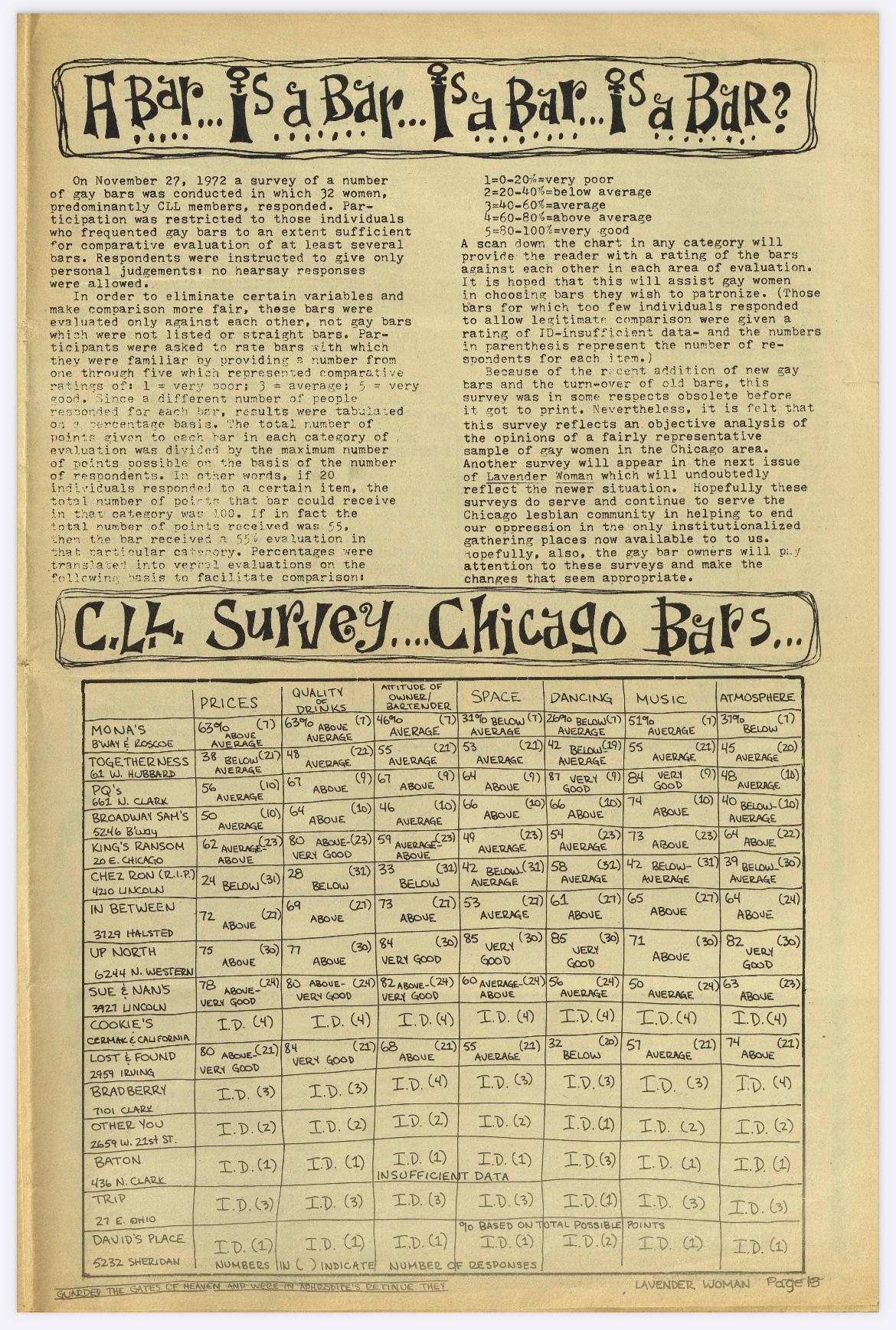

Despite the occupational hazards, lesbian bars thrived. Because these businesses couldn’t exactly advertise with billboards and commercials, lesbian travel guides were created to advise “friends of Dorothy’s” on which bars, bookstores and other gay-friendly venues they should make a point to visit. Valerie Taylor, a lesbian pulp fiction author, would include the locations of real Chicago gay and lesbian bars in her books to help lesbians find accepting spaces.

Now, however, times have changed. Lesbians no longer need to frequent bars and bookstores to form a community when that community exists loud and proud around them. With an ever-growing increase in support and allyship for the queer community, people no longer need to use code words and clandestine bars to find others like them.

CeCe Wacht, a Chicago resident, says she is in favor of having more spaces dedicated to queer women, even if the need for them isn’t as tangible as it was several decades ago.

“It’s just really special to be able to walk into a space and know that there’s a lot of other people with the same or similar identity as you,” Wacht said.

Although Chicago is home to a vibrant queer community, one which includes one of the most famous gay neighborhoods in the U.S., many of the city’s queer spaces seem to cater mostly, if not exclusively, to gay men. While the number of gay bars in Chicago has dropped over the past few years, they still outnumber lesbian bars by quite a large margin.

Even though she frequents Boystown, Wacht enjoys having spaces that align more accurately with her identity. It may be easier to find community with other queer women now than it was 50 years ago, but the desire for lesbian spaces is still alive and well.

“I feel like that’s very needed in the lesbian and queer women community because it can feel so, so lonely,” Wacht said.

The idea of wanting a space separated from men, even queer men, is not new, but with less lesbian bars existing nowadays, it can be hard for queer women to find these spaces. Chicago’s gay bars are welcoming of every queer identity, but Wacht believes that there is not as much of an emphasis on the wants and needs of queer women as there is on queer men.

“I feel like it just continues the pattern of things just being surrounded by men,” Wacht said. “It’s weird, because I feel like it’s just another subsection of the patriarchy. Even within the queer community, it’s still so male dominated.”

Chicago is home to two official lesbian bars: Dorothy, which is located in Humboldt Park, and Nobody’s Darling, which is located in Andersonville. Both bars opened after 2020 to celebration from the communities that they serve.

The interiors of the bars are starkly different. Dorothy has a laid-back atmosphere, with everything from the walls to the furniture drenched in orange to evoke a 1970s ambience, and it hosts events ranging from raucous drag shows to silent book club meetings. Nobody’s Darling, which was named after the Alice Walker poem titled “Be Nobody’s Darling,” sports a sleek black interior and loud, upbeat music with a patio for guests to relax on.

In addition to creating a safe space for queer women, Nobody’s Darling also emphasizes itself as a safe space for queer people of color. The bar is owned by two Black women, Renauda Riddle and Angela Barnes, and over 90 percent of the spirits they stock in the bar are Black-owned, POC-owned or women-owned.

Dentel says that in the past, women of color were often excluded from Chicago’s lesbian bars. Non-white patrons would often be asked for multiple forms of identification in order to be granted entry, a caveat that was not enforced for white patrons. Although lesbian bars populated by women of color did exist on Chicago’s South Side, they aren’t as documented as the primarily white lesbian bars on the North Side, leaving a gap in Chicago’s lesbian history.

“There’s the idea of archival silence, and who is represented in an archive and who is not, and some of it is very intentional exclusion of people,” Dentel said.

Casey Groulx, a regular attendee of Nobody’s Darling, says that it filled in a gap for her that she didn’t know she was missing.

“I’ve always spent a lot of time at gay bars, but I didn’t realize how much better I would like going to lesbian bars,” Groulx said.

This seems to be a common thread for customers of Dorothy and Nobody’s Darling: they didn’t know what they were missing out on at other queer bars.

“I like the atmosphere a lot,” Groulx said. “I feel like at other gay bars the music is always so loud, and it’s more of a club vibe. But at Nobody’s Darling, it’s a lot less intense and you can get to know new people better.”

Although the reception of these bars has been positive, other patrons have some critiques.

While Wacht has enjoyed the time she’s spent at Chicago’s lesbian bars, she wishes that there were more lesbian spaces that catered to a younger audience. At Dorothy, it seemed to her that everyone was either already coupled up, or within their own group of friends, making it more difficult to meet new people, especially ones her age.

“I feel like especially now … people are coming out and realizing they’re queer sooner and sooner in life nowadays,” Wacht said. “So, I think it’s really important to have younger queer spaces, too.”

Although Dorothy wasn’t exactly the experience she was hoping for, it still provided a space for her to be completely herself, which she counts as a win.

Although lesbian bars have dwindled, the ones that exist now are still serving the purpose that they were originally created for: to give queer women a chance to find a community for themselves in space dedicated to their happiness and safety. Lesbian bars are not just bars, but rather a love letter to queer women that says, “You are welcomed, you are loved and you are not alone.”

An ad for Augie & C.K’s bar inside a lesbian travel guide. Photo courtesy of Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

The cover of a lesbian travel guide published in 1988. Photo courtesy of Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

A ranking of Chicago lesbian bars published in the Lavender Woman periodical. Photo courtesy of Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

Header by Alexis Phelps

NO COMMENT