Former Irish president Mary Robinson visits DePaul

Mary Robinson, the first female president of the Republic of Ireland, visited DePaul last Friday, February 28, following her donation of close to 900 books of Irish poetry, prose, plays and literature from her personal library to the university’s John T. Richardson library.

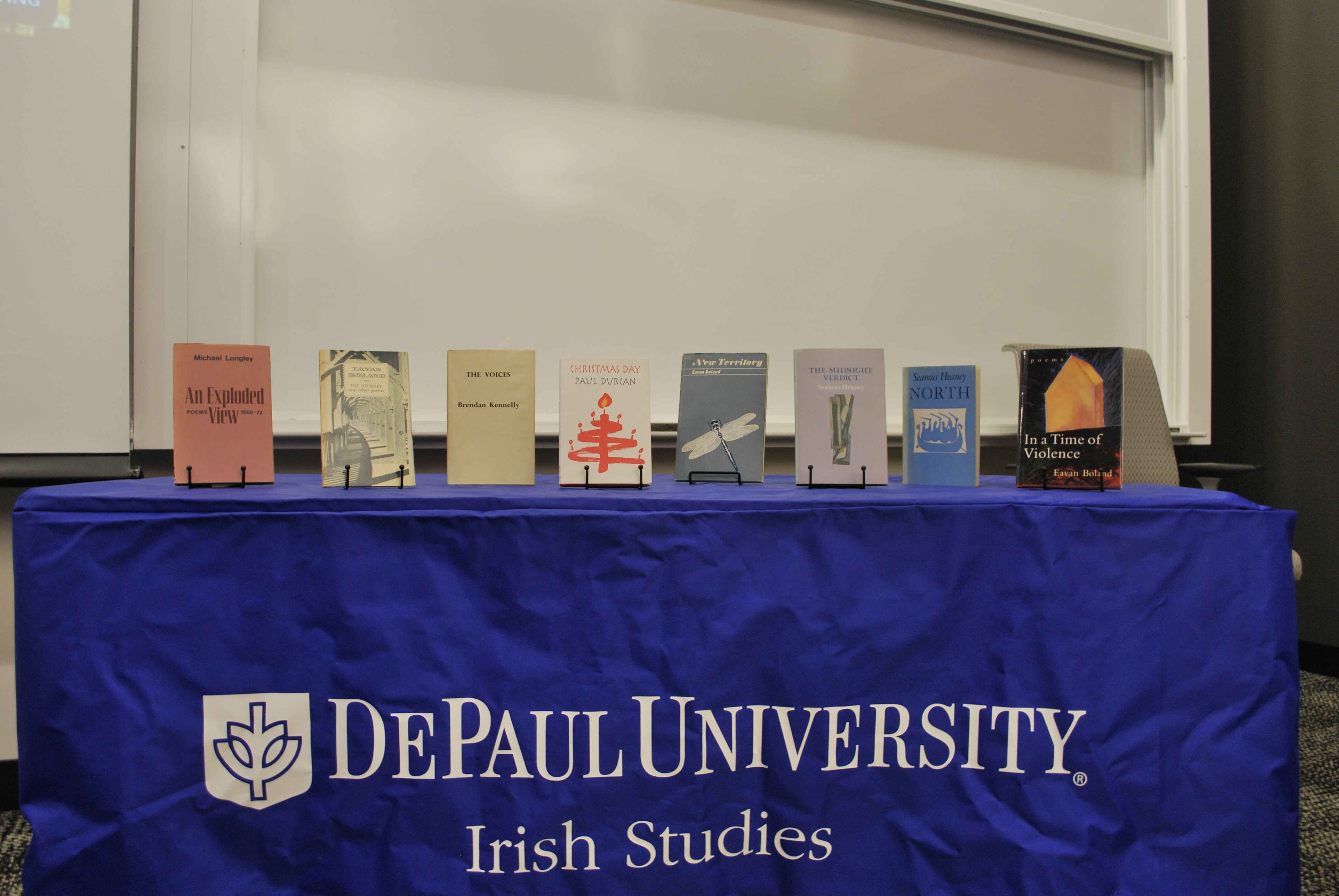

The collection being donated includes the works of W.B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney — each of whom received the Nobel Prize in Literature. The collection also includes works by poet Eavan Boland, a close friend of Robinson from her time at Trinity College Dublin. The two remained friends until Boland died in 2020, and Robinson expressed her desire for the collection to be named the “Eavan Boland Collection.”

According to Robinson, Boland was a huge inspiration for young poets, especially women. She had “an incredible presence for them, an incredible mentor, incredible leader, somebody who had really broken through and opened up the space for a different kind of writing.”

Aside from the donation of the collection, Robinson also gave a talk that took place in McGowan South and lasted about an hour.

John Kaiser, a senior at DePaul and part of the Irish Studies program, attended the talk. “First, I want to thank President Robinson for one, donating her literary collection to our John T. Richardson Library for the use of students and the community, and two, for coming out, giving such a thoughtful, insightful, hope-filled talk,” he said.

Kaiser was impressed by attendance, but expressed frustration that DePaul President Rob Manuel did not attend.

About 140 students, faculty and community members attended the talk, some of whom traveled from out of state.

Robinson began her career studying law at Trinity and then Harvard University in the U.S. in the 1960s. After completing her masters in 1968, she returned to Ireland to practice law, inspired by the American Civil Rights Movement. In 1969, she became a Senator in the Seanad Éireann and a part-time junior lecturer of law at University College Dublin (UCD). Both positions awarded her small salaries, allowing her to practice whichever type of law she pleased.

“I really wanted to use law as an instrument for social change,” Robinson said. “I didn’t want to make money from law. I wanted to make change.”

This philosophy would follow Robinson for the rest of her life and career.

In early 1971, Robinson began a legislative fight for family planning in Ireland. This was not only a fight against societal and political norms, but also the Catholic Church as 93.9% of the country was Catholic in 1971, according to census data.

“Clearly, women needed reproductive health,” Robinson said. “We proposed to introduce a bill to amend a criminal law that criminalized condoms. Little did I understand that I had tapped into something. I was talking about sexuality. I was talking about relationships, and it was hugely unpopular.”

Nine years later, in 1980, the Health (Family Planning) Act was signed into law allowing the sale of contraceptives by registered pharmacists to those with a valid medical prescription. In 1985, after much debate in the Dáil — Ireland’s main legislative branch — and major pushback from the Catholic Church and the conservative Fianna Fáil party, the law was amended to allow non-medical contraceptives available to those over 18 in pharmacies.

Robinson stepped down from Seanad Éireann in 1989 and was elected president in 1990 with support from both liberal and conservative constituencies. She served as president until 1997, and was instrumental in the peace process in Northern Ireland that resulted in the Good Friday Agreement, formally ending The Troubles.

“Going into West Belfast helped,” Robinson said. “It was very controversial, but was also clearly trying to make peace, and making peace means you take risks. You make peace with your enemy, not with your friend.”

West Belfast was an epicenter for violence during The Troubles, and Robinson’s visit included a meeting with controversial Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams. The meeting in 1996 became known as the “historic handshake,” as it was the first time an Irish head of state had ever publicly shook hands with Adams.

Kaiser was particularly struck by this part of the talk, especially in what he considers a very divided world.

“We can’t find a solution if we’re unwilling to approach each other with humility, dignity and, most importantly, empathy,” he said.

Following her presidency, Robinson joined the United Nations as High Commissioner on Human Rights. During her tenure from 1997 to 2002, Robinson focused on integrating human rights into all UN activities and monitored conflicts in Yugoslavia. She also traveled to places like Rwanda and South Africa and became the first high commissioner to travel to China.

While she did not initially focus her work in the UN on climate, she eventually came to recognize the intersectionality of the issue. “I then understood that the climate and nature crisis was very serious, but there was another part of the UN dealing with it,” Robinson said.

In her mind her commission was focused on human rights, gender equality, rights of people with disabilities and the rights of Indigenous people.

“I didn’t connect it with climate at all,” she said.

However, on trips to different African countries in 2003, she came to recognize how climate change went hand in hand with the issues she had been working on for her entire career.

“They were already feeling the worst impacts of the climate shocks and the rainy seasons weren’t coming. There were long periods of drought and then flash flooding that destroyed the whole village, and no insurance, no anything, and it was happening all over. And women were saying to me, is God punishing us? What is happening?” Robinson said.

Now, Robinson is a member of The Elders, an organization founded in 2007 by Nelson Mandela as an “independent group of global leaders working for peace, justice, human rights and a sustainable planet.” According to Robinson, the group focuses its work on existential threats, which include the climate crisis, nuclear weapons, public health, artificial intelligence and even threats to democracy worldwide.

According to Robinson, The Elders are focused on “promoting long-view leadership,” meaning leadership that focuses on the future, rather than the immediate present.

Working on these issues requires cross-generational collaboration, something Robinson strongly supports.

“We do need different generations at the table now,” Robinson said. “I was very pleased to see that the future gave a lot of hope for young people to be more at the table.”

Header photo by Jana Simovic

NO COMMENT