DePaul students consider the future of futurology.

Inside a retired movie theater on DePaul University’s Lincoln Park campus, a small audience — students, parents, a smattering of suits and a couple of professors — gathered Saturday morning to do the impossible; they wanted to look into the future.

The event was organized by a local chapter of the political science national honor society Pi Sigma Alpha and revolved around a series of “InsTED” talks. Possible copyright infringement aside, the presentations operated in the same spirit of their namesake with a format split between presentation and discussion. On Saturday, four political science students from across the Midwest spoke via video on the future of “X”; in this case, the future of education, politics, health and commerce.

But five minutes into the first presentation, I found myself distracted by a word that popped up periodically for the rest of the day: futurology, or to be more specific, futurologist.

I was distracted because it sounds made-up; like a discipline for college dropouts with an affinity for tarot cards, or something. Does Harvard have a School of Futurology? Do futurology degrees exist? How do you study something that hasn’t happened?

After a weekend of diving down rabbit holes, I came away with a few observations. First, the field is about as organized as you’d imagine. On the Wikipedia page for “Future studies,” the second sentence admits that “there is a debate as to whether this discipline is an art or science.” Some stick with “futurology” and “futurologists,” others call it “futurism” and themselves “futurists.” The University of Hawai’i Manoa has the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies, while the Association of Professional Futurists constitutes a group of loosely affiliated academics from across the world. At any rate, futurology’s low profile seems to suggest that is has something of a branding problem.

Jules Verne (right) and H.G. Wells (left). Image compilation courtesy of the Society of Satellite Professionals International.

That said, they exist! Some futurologists draw their field’s origin to a source that’s as surprising as it is obvious: science fiction. Writers like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells were among the first and most prolific to draw a line from the technological advancements of their time to a vision of the future, using the trends of science and society to drive their readers’ imagination upward and onward. Wells’ “Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life” is remarkable in retrospect for how much it got right. Published in 1901 and written in the form of correspondence from 2000, Wells predicted the population shift away from urban centers via trains and cars, the sexual revolution following the advent of birth control, a pre-cursor to the European Union, and an American-led world order — in his words, “a great synthesis of the English-speaking peoples.… the head and centre of the new unity will be the great urban region that is developing between Chicago and the Atlantic.” Of course, he also got plenty wrong.

“It doesn’t look pretty,” DePaul senior Michael Mulligan said, “but it doesn’t look ugly either.” Inside the Schmitt Academic Center, a video of Mulligan speaking behind a podium played, presenting his prognosis for the future of education. After listening, I had to disagree; it sure sounded ugly to me.

With the world’s access to information expanding every day, Mulligan argued, it was impossible for our country’s current model of higher education to survive. While he and the rest of the speakers stayed conspicuously clear from time-specific predictions, he pointed to present evidence to illustrate the dilemma; a reliance on online classes and adjunct professors suggested cracks in the traditional format of college classes, while the increasing commercialization of education would encourage specialization and splintering. One of his most interesting predictions was the arrival of a “market-based” university, where the business world would invest in personal education pipelines to funnel in their future employees straight from graduation day.

Then came the future of politics, courtesy of Purdue University’s Michael Turinetti. Following the previous discussion on education that featured the sentence, “I’m anti-artificial intelligence because I want to survive,” Turinetti’s vision of political future was remarkable in its lack of radicalism. He described the “global scaling effect,” the idea that increasing globalization would bring the world closer and gradually move the power from the local level of government up towards an institution at the international level. Eventually.

“How it looks,” he told the room more than once, “I don’t know.”

From the outside, Turinetti’s prediction for international order looked like a slightly buffed United Nations — sans the Security Council with some actual taxation power. Of course, when the discussion portion rolled around, he and his research partner were asked in as many words if they’d actually been following the news for the past six months: with Brexit and the results of the 2016 election, it seemed like the world was just about done with globalization for the time being. Their response was that we were experiencing a pendulum; while the world was swinging to the right today, we’d be back on track in due time.

It was around this point that I began to wonder why I’d shown up today. Not because I wasn’t enjoying myself, nor was I unimpressed with the talks themselves; the ideas were interesting and the discussion was stimulating. At the same time, I couldn’t escape the sense of futility. We were, after all, just sharing guesses. On top of that, we were students; it’s our job to not actually know things. What were we really learning?

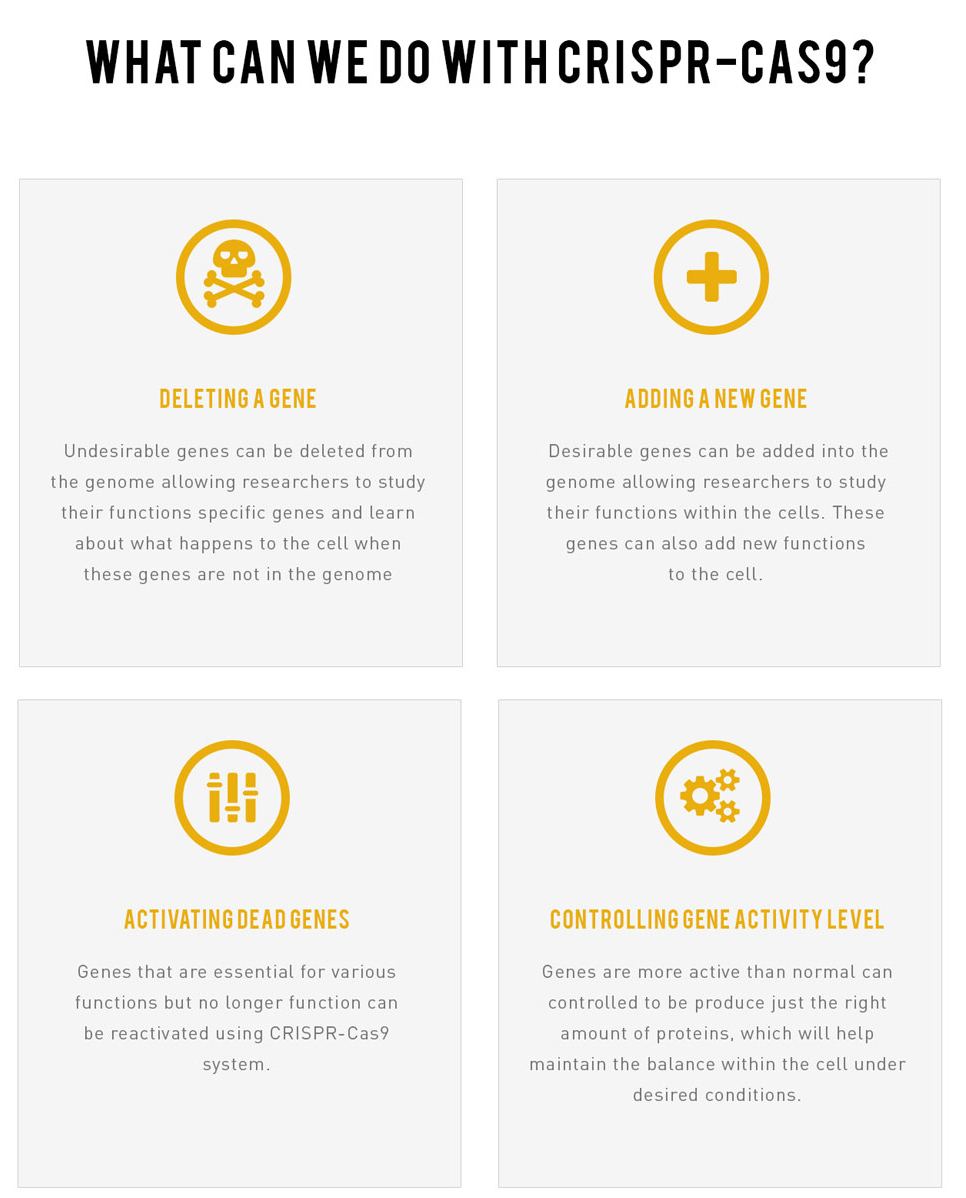

The day went on. After lunch, Jared Koehler of North Park University presented the future of health by ruminating on CRISPR-Cas9 — a gene editing tool that Koehler claimed is the biological equivalent of what Google Maps was for cartography. The ideas and information behind DNA manipulation have always been there, but the execution — and more importantly, simplification — was game-changing. Being able to edit genes in other animals, plants and eventually humans would change the nature of life on earth, whether it meant the end of disease or the advent of “designer babies,” like the 1997 movie Gattaca. This future in particular was so massive in both its promise and danger, it was hard to do anything but marvel at its potential.

Infographic courtesy of Futurism.com

As his video presentation began to wind down, Koehler also echoed the day’s theme, perhaps better (or more infuriatingly) than any other speaker. “If I’ve left you with more questions than answers today,” Koehler said, “I’ve done my job.”

Finally, the day ended with the future of commerce. Presented by DePaul’s Robert Kearney, his prediction seemed more concerned with the immediate future than that of twenty or thirty years down the road. According to Kearney, we could expect shopping trips and even delivery services to become a thing of the past; in-home 3D printers with cartridges of all possible materials would allow us to create the things we bought, like renting a movie that would expire after it had been watched. He didn’t know if we could expect that kind of access for all products — a sweater is somewhat easier to manufacture than a computer, for instance — but he wouldn’t rule it out either.

Obviously, this profound change to our longstanding notion of supply-and-demand would create unimaginable shockwaves. What would the world look like without industrial manufacturing? This, like a lot of the other ideas the group spent the day wrestling with, suggesting the oncoming “democratization of everything,” as Koehler said during discussion at one point. On its face, as a sort of buzz-wordy, movie-title-sounding phrase, it sounds pretty cool. But would it be? Then again, did it matter how we felt about it if it was going to happen anyways?

Once the event was over (and after some obligatory networking), I had a chance to talk to Professor Richard Farkas. After teaching political science at DePaul for over 40 years, he helped organize the talks as the faculty advisor to the local chapter of Pi Sigma Alpha. And, when I asked him the question I’d been mulling over all day — “what was the point?” — he looked at me with an expression that somehow captured all of the following: bemusement, disappointment, skepticism of my skepticism, and a twinkle.

“My reaction is almost visceral,” he responded. “I think there is nothing that has a greater point.”

He gestured to the wall behind me.

“Would I like to see a mile past that wall? Of course I would,” he said. “I’d like to see as far in front of me as I can. Imminent danger; I’m paddling down a river. The next bend could be a waterfall, could be rapids — could be a monster.”

Then, a story from his classroom: “I would pick out the biggest, strongest guy in my class,” Farkas said. “And I said, ‘I’ll race you. If I win, you all will have to be happy with your grades. If the student wins, I’ll give you all A’s.’”

“I never lose,” he said. “Ever.” The catch, of course, was that the student would have to run the race backwards.

He waved his hand to the empty room, as if to repeat the question: the point?

“The point is to get you facing forward,” he said. “I’m not sure what you see versus what she sees and what he sees. But I don’t much care about that. I want you to see whatever you’re looking for.”

NO COMMENT