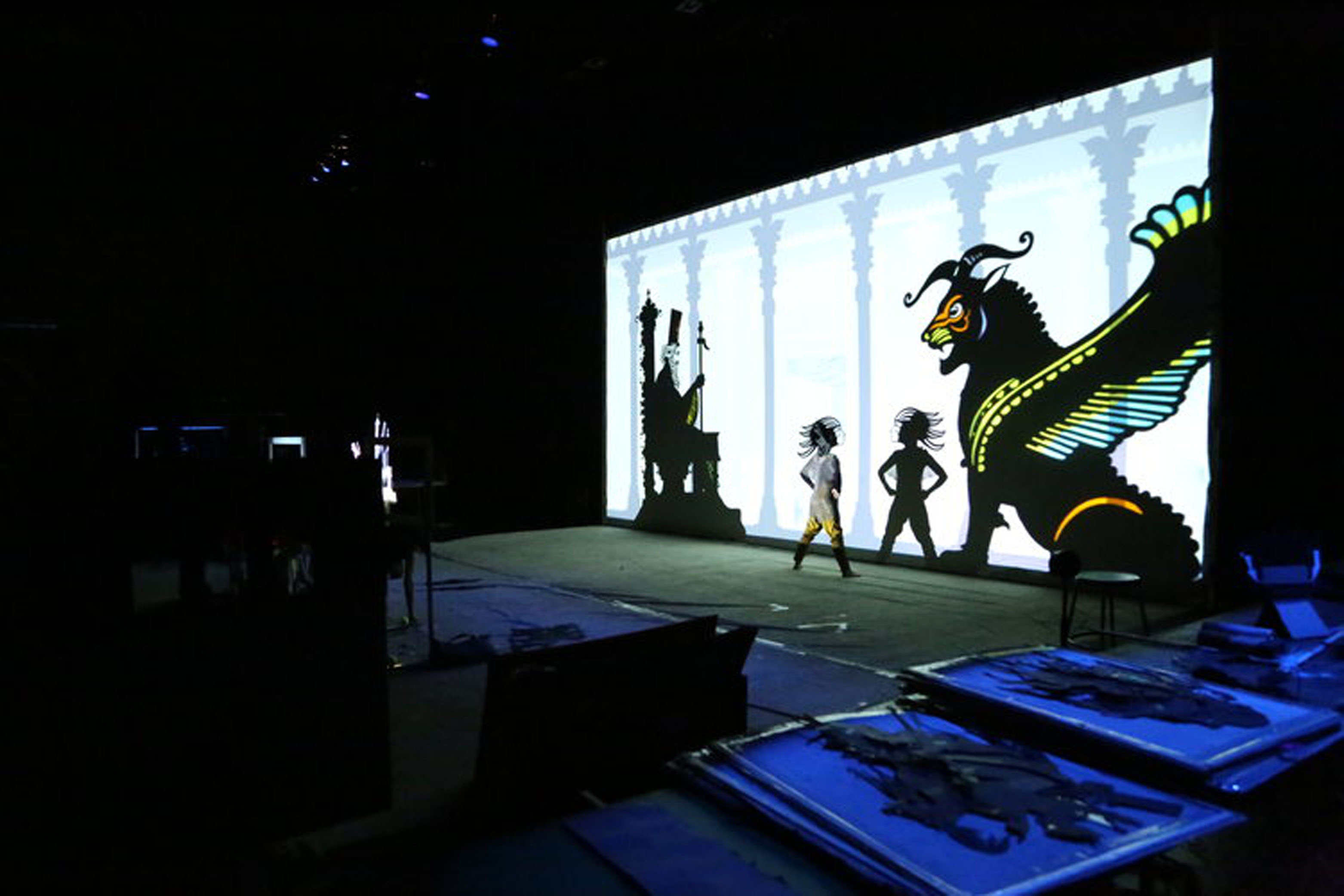

When trying to explain the many unique sequences in Hamid Rahmanian’s shadow puppet epic “Feathers of Fire,” it’s hard to narrow down one that stands out as the definitive takeaway. Do you speak of the incredible action sequences that combine live performance with handcrafted cutouts and stellar lighting and shadows? Do you attempt to recount the narrative, a fusion of Shakespeare and Persian myths brought to life through music, colorful backdrops and performers? Or do you look to the comedy, with 2-D puppets shifting and flailing around their human co-stars? For all these moments of visual and storytelling splendor, there was one moment that drew the most awe and applause from the audience, and that was after the show was over.

The lights dimmed, the curtains rolled up, and Hamid stepped out onto the downstage area to speak with the audience, proclaiming that he had something to show everyone. Suddenly, the crew moved back into place, this time with clarity into how the entire production was made possible. It was possibly an artist’s ideal response from a crowd, as we all sat there watching the puppeteers and performers reenact several scenes without a veil. We had transitioned from thinking, “Oh my God, how did they do that?” to, “Wow, now I want to do that.”

Photo courtesy of kingorama.com

“Feathers of Fire: A Persian Epic” is a shadow puppet live performance created, directed and written by Hamid Rahmanian and hosted by the Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival. The festival is an international bi-annual showing that brings a variety of puppeteers to the city. The play was inspired by the myths and legends found in Shahnameh: the Persian Book of Kings, described by Mr. Rahmanian himself as the “Persian Odyssey.” The story that followed was one that was clearly meant to be understandable and enjoyable to audiences of any age, yet also managed to tackle several engaging subjects, such as man’s relationship with Earth and the immortal beings that rule it, as well as bitter tribal rivalries interfering with the affair of two young lovers.

The central protagonist is Zal, the son of a renowned Persian general, whose birth causes his mother to die. Zal’s birth is thus seen as a bad omen, so his father takes him away into the mountains. From there the story shows the developing life of Zal, and how he overcomes struggle of escalating war with other Persian armies as well as the perils of mythical beasts. But this isn’t just a plot about battles and giant monsters; it is about family and the sacrifices one must make for their kin. It asks whether someone should be more loyal to their state and title or to their own family, and if “family” is limited to people related by blood. It’s a warm and uplifting tale told in a dark mythological world, something that just about anyone could find catharsis in, in some way.

Even more impressive than the story, however, is the way it is told. The world the audience becomes absorbed in was arguably more visually striking than that of some recent animated films, and this is all done live. Now, the actors, cutout puppets and overlaying backgrounds were placed in front of two projectors which were placed in the back casting shadows on the large screen in front of the audience. An actor running in place in front of an animated backdrop with hand drawn armies gave the sensation that a character was charging headfirst into battle. On the other hand, an actor or puppet placed very close to the projector upstage gave the illusion of a towering figure overlooking another when viewed by the audience. The two projectors upstage run at separate times, and the puppeteers and performers would play out one scene while the next scene was set up with the other projector. Thus, one projector could be turned off and the other turned on almost simultaneously, creating a new series of shadows cast from the actors and puppets that the audience saw. With all this, which constituted over 1000 different sound and transition cues, it managed to transport the viewer into the world of these characters seamlessly.

The puppets, handmade by Neda Kazemifar and Spica Wobbe, gave an incredible amount of humor as well as drama into the story. Whether it’s a stationary kneeling peasant, who, when asked to rise at the request of Zal, replies, “I’m actually quite comfortable holding this position your majesty,” or an intricately designed sea monster with multiple moving parts and booming sound effects accompanying it, the two-dimensional puppets give off a wide variety of character. The production for these shadow cut-outs took roughly 18 months, and in many scenes, it paid off.

Photo courtesy of kingorama.com

One of the biggest highlights of “Feathers of Fire” is undeniably the costumes. These were designed by Dina Zarif, and they added even more to the story. The actors’ bodies are silhouetted, and their faces are obscured by large two-sided masks that exclusively show the profile image and details of characters. The trick was having two different sides to the mask that stuck to the sides of the actor’s face at a concave angle, allowing the actor to see what was in front of them clearly but also allowing the character’s face to shift from side to side very quickly, giving the actors a lot more movement and fluidity that the show benefited from.

Hamid Rahmanian said the original goal of this production for “Feathers of Fire” was to effectively translate the original Persian Book of Kings myths to citizens in the Middle East that now predominantly speak Arabic. However, what he and his team have created is something that speaks to the universal human language of passion. Every beat in the musical score, every unique shadow cast on the screen, every joke and intimate moment between the characters strikes at the core of what makes both live performance and puppets so necessary in today’s largely internet media dominated era. There is no cynicism here, no condescending to younger viewers, nor is there any insult to the intelligence of dedicated audience members. There is simply a warm story to be told, and an unapologetically original and colorful way to tell it.

After completing their Chicago performance, “Feather of Fire” was moving on to the European part of their tour. Unfortunately, on the last show, audiences learned that a member of the crew will be unable to accompany the show to Europe due to uncertainty about getting back into the country after the Trump Administration’s travel ban recently put in place. The production team is an international group of artists from different countries including Iran, one of the six nations included in the travel ban. At the show I attended, I saw the front several rows of the audience filled with children, all of whom shot their hands into the air once it was time to ask questions about how the show was made. After standing up and collecting my things, I heard a couple behind me singing the production’s praises; one said that, when he got home, he wanted to try to make shadow puppets of his own. This is what the show gave these people; not just a fun night, but a lso the encouragement to go and create art on their own. In this day and age, we need more exposure to other cultures and different stories, not less. Costume designer and actress Dina Zarif, during the final night the show performed in Chicago, left the audience with a plea: “Please take action, do something. At this point, it really doesn’t matter who you voted for; it’s all about humanity.”

Trailer by finecutstudio.com

Header image courtesy of kingorama.com

For additional information and ticket purchases, visit http://www.chicagopuppetfest.org/

NO COMMENT