From Vietnam protest to Chicago sports dynasties, Chuck Davidson captured it all

It’s early June 1993, and helicopters are hovering over a ritzy country club in Scottsdale, Arizona – 40 minutes north of Phoenix. A car cruises around the perimeter of Desert Highlands’ walled-off, 18-hole, Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course in search of something elusive, newsworthy and well-known around the world.

The two men in the car desperately need to find what they are looking for; it’s how they make a living. But more importantly, it’s what they love to do. After some searching, the target is in their sights.

One of the men races from the car in pursuit, lugging nearly 30-pounds of equipment, and hops the three-foot barrier onto the meticulously kept grounds. Camping out behind a cactus he is poised, ready. This is his calling, his life’s work. He slowly steps out from around the spiny plant, with his shoulder-mounted CBS News video camera.

Unfortunately, his mark spots him.

“Chuck, what the f— are you doing out here?” barks Michael Jordan.

But the then three-time NBA MVP and one of the most instantly recognizable athletes knew exactly what Chuck Davidson was doing on the private desert course: his job.

CBS Chicago’s lead sports cameraman stares down Jordan while his Channel 2 reporting partner waits in the car.

Davidson is there because rumor has it that Jordan scheduled a round of golf with Charles Barkley on an off day during the ‘93 NBA Finals.

A shot of the NBA’s leading scorer teeing it up and smoking cigars with the braggadocious Phoenix Suns power forward, who had recently been crowned league MVP, would be more than tabloid fodder. It would be newsworthy at a time when Jordan’s Bulls owned not only Chicago sports news coverage, but national attention as well.

For a Chicago TV station desperate to find any edge during a period of intense competition, Jordan and Barkley mucking it up on the greens meant notoriety and hard cash — or at least local TV bragging rights and perhaps a potential boost in future advertising sales.

Davidson hears Jordan over the helicopters above, and despite his playing partner being similar in stature to the “round-mound-of-rebound,” the videographer instantly realizes Barkley isn’t playing with the Chicago Bulls star. However, he doesn’t have time to worry about that because the man who would appear on three out of four Sports Illustrated covers that month is already jokingly laying into the determined cameraman he is well acquainted with.

“Where’s Howard [Sudberry],” Jordan bellows. “He’s hiding isn’t he?”

As one of the city’s most well respected and dedicated sports cameramen, Davidson knows he needs to get at least a few seconds of Jordan immersed in one of his favorite non-basketball settings. So, he picks his first words carefully.

“Yes, he’s back in the car,” Davidson says coolly. “Look, Mike, I just want to get a shot of you hitting off the tee then I’ll leave.”

“Alright, Chuck,” Jordan calls back.

With his Airness’ pardon and approval, Davidson prepares to film.

Jordan tees off with his signature unorthodox yet powerful swing. Afterward, the 6-foot-6 walking-legend strolls by Davidson on his way up the fairway.

“You can tell Howard to go f— himself,” Jordan says wryly.

Born on Chicago’s North Side in 1943, Chuck Davidson grew up surrounded by baseball. His father, who was born blocks away from Wrigley Field, passed on the sport to his son. The self-proclaimed baseball nut memorized the numbers of as many players as he could as a child.

“I would always come home and watch the Chicago Cubs television broadcast, and they were in black and white when I was a kid,” Davidson said. “I remember the first time I went to Wrigley. Seeing the green grass and the blue uniforms, it was almost surreal.”

Davidson and his family moved to DeWitt, Iowa, a town of roughly 2,500 people, after he turned 10. But the small town only increased his passion for sports, which became a year-round obsession. DeWitt saw him play baseball nearly every day at a field just blocks away from his house, no matter how many kids they could muster. “Then, when basketball season came around, we would go scrape snow off of driveways to play one-on-one,” he said. “But I was always too little to play football.”

He attended St. Joseph Catholic School, which at the time was kindergarten through 12th grade. Davidson played both baseball and basketball in school. But he also became fascinated with something else during his formative years. “By the time I was in high school, I already figured I wanted to be in television,” he said.

Davidson finished near the top of his class of 23 before he matriculated to the University of Iowa.

As a college student in Iowa City, he covered city hall and the police beat for the university’s radio news station. He graduated with a B.A. in radio/television journalism in June of 1965. That same month Davidson moved nearly 130 miles west to Ames where he woke most days at 3 a.m. to head to work.

The eager young journalist voiced sign-on radio at Iowa State University-based WOI, which at the time served as the ABC affiliate for the Des Moines area. Davidson enjoyed his first real job, but he admitted his shortcomings during his days tearing off wire copy in the predawn hours. “I knew I was bad at it,” he said. “I’d say three words and I’d kick two of them.”

Davidson began to experiment with photography and video while at the station, often spending his non-working afternoons with the television news crew. The easy-going young man, who had not yet married his wife, passed the time by learning more about the business and building relationships — not in the purely self-focused networking manner.

“Everybody liked him because he was a generous man and a good person,” said long-time Chicago sports reporter Rich King, who worked with Davidson at CBS for a few years.

Still, WOI, which broadcast AM, FM and TV, fired him less than a year into his early on-air radio news career making $5,800, because, in his own words, he was “horse s—.” Undeterred and only slightly off course, Davidson moved to Lansing, Michigan in April 1966 where he transitioned to a full-time cameraman.

His arrival at the CBS affiliate, WJIM-TV coincided with local and national turmoil surrounding the civil rights movement. Along with heightened racial tensions, college campuses around the country began to voice their vehement disdain for the Vietnam War. He spent most of his early days in Lansing, many of which were actually at night, shooting video of riots and protests.

In the summer of 1966, while parked at a stoplight on his way to cover a firebombing near the state capitol building, with the WJIM station logo plastered on the side of his car, a massive piece of busted up sidewalk concrete came flying through his passenger side window.

“If someone would have been sitting there, they would have been killed,” Davidson recalled. “That was my first brush with problems, but not the last.”

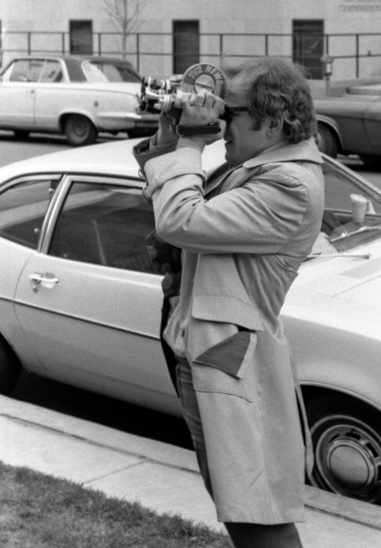

Photo courtesy of Chuck Davidson.

Davidson spent two years covering mostly hard news in Lancing during a period of social and political unrest. Members of the Students for a Democratic Society once stole his video camera. And a police officer even tried to strike Davidson over the head for filming him during an aggressive campus anti-Vietnam protest. If not for his bulky TV camera, the blow might have caused serious damage.

“It was a tough deal, there was a lot of danger, doing what I did,” he said. “But when you’re young you’re kind of a go-getter, you have a kind of an altruistic look at what your profession is and how important it is to the public good.”

However, while society-altering demonstrations and speeches gripped the country, Davidson gravitated towards athletic dramas and sporting heroics that unfolded inside stadiums and arenas.

“As you get older you think, I have covered too many body bags and picket lines and school board meetings,” he said. “I just kind of gradually moved towards sports, which fell much more in my range of interests because I loved it, and it got me into less dangerous situations.”

His employers would slowly but steadily oblige.

Although Davidson was just beginning to hone his newfound craft in Lansing, like most people who work in news of any kind, he began to look for the next logical career progression. This almost always means finding a larger market. So, about a year after the riots of 1967, Davidson made two professional leaps at once. He doubled his salary at Detroit’s WJBK-TV and transitioned into a sports videographer nearly full-time.

Davidson spent most of his career on call and rarely worked nine-to-five. “Television is like being a cop, in the news business,” he said with pride. “There are no weekends or holidays, they’re all just normal days.”

His time in Detroit revolved heavily around the Tigers — who won the ‘68 World Series during his first year at CBS. He spent hundreds of hours during the roughly six-month long MLB regular season shooting games at old Tiger Stadium for short nightly news highlights as foul balls zipped past him behind home plate. Curriers or taxicabs often swung by the stadium to pick up the first couple of innings’ film while Davidson plugged away searching for a few standout eye-catching moments until the final out.

Davidson would go on to cover almost every Tigers home game and nearly all of their playoffs games for the rest of his Detroit tenure.

He traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1979 to shoot the NCAA Final Four featuring Earvin “Magic” Johnson vs. Larry Bird. Davidson, who had covered Johnson in both high school and then college, covered the first time the two men — whose rivalry and star power that would go on to help define the NBA for most of the 1980s — took to the national stage as rivals.

Davidson captured much of the golden age of football at the University of Michigan, where Bo Schembechler’s Wolverines won 13 Big Ten Conference titles in 21 years. He followed the team to multiple Rose Bowl games in Pasadena, California. The Tigers World Series victory in 1984 capped his time in Detroit as Davidson once again made a large and logical career move.

One of his former colleagues offered him a job at ABC in the country’s third-largest media market based on his reputation behind a camera and his calm, hard-to-find-disagreeable demeanor. Despite his initial apprehension about moving on, based mostly on his standing and seniority in Detroit, Davidson and his family decided to head to the city he grew up in.

However, just over a year into his new job, in April 1986, ABC Chicago laid off Davidson and more than 20 others on the same day. The station conducted what Davidson referred to as a purge similar to the recent wave of large, one-day job cuts at ESPN, despite having been assured that ABC hadn’t laid anyone off in 25 years before he packed up his family and moved.

Without hesitation or a moment’s self-pity, he applied to work at CBS Chicago. The station happened to be looking to hire experienced people. But Davidson was more hopeful because the channel already used his footage when the Tigers played the Chicago White Sox, which meant they already understood the quality of his work. CBS hired Davidson only weeks later.

CBS 2’s Johnny Morris – a one-time Chicago Bear who hated to get beat on a story – also happened to be “the most powerful sports director in the country,” according to Davidson. And Morris also happened to handpick his videographers.

The station’s former number-one sports videographer retired before Davidson’s arrival and his replacement didn’t live up to the sports director’s standards. So Morris gave Division a shot since he knew the cameraman’s eye for details and baseball storylines had already proven exemplary. In August of 1986, Davidson got rushed up by helicopter to Platteville, Wisconsin to cover the Chicago Bears training camp.

After that trip, Davidson remained CBS Chicago’s lead sports cameraman until he retired.

Photo courtesy of Chuck Davidson.

Davidson really began covering the Bears after they won Super Bowl XX in 1986. Despite not winning another championship, the ‘85 Bears and its biggest names captivate many Chicago sports fans to this day.

Back then, teams thrived on outside exposure and often openly welcomed it. The Bears’ offensive line ate weekly dinners that they encouraged Davidson to shoot.

At the time, the media coverage helped clubs gain exposure because players, teams and the league could not easily self-promote – where today the NFL and all of its teams have their own full-scale media and public relations departments that actively try to control a team’s publicity while drastically seeking to minimize outside media access.

He filmed practices at both new and old Halas Hall, north of the city in Lake Forest, on a daily basis during the season, always aware of the most recent storylines while constantly searching for new ones. Davidson’s footage, for most of his career, mainly appeared in cut-up 60 to 90 second packages that aired on the nightly news.

“Chuck was one of the best, if not the best sports shooters in Chicago for a lot of years,” King said. “And everybody loved him because he was really good with people — not just with the athletes, but everyone from the security guards to beat writers to other cameramen.”

Davidson’s film proved so effective because it was simultaneously immense, yet efficient. His bosses loved him for his eye behind the camera. Not only did he produce well-framed, focused and coherent footage that followed continuous action, he also always knew what the storylines were at all times.

The CBS videographer worked practices, games and everything in between with an intimate and well-researched understanding of the players and narratives that mattered most. He could then shift gears without hesitation if he saw a different, more newsworthy event occurring.

In 1988, Davidson raced to film Bears’ cornerback/safety Shaun Gayle after he fractured a vertebra at the Pontiac Silverdome in Detroit. “Chuck saw Gayle being taken off on the stretcher and he shot it,” King recalled. “It sums up what a professional he was because the Bears were upset with him for filming that, but it was solid journalism.”

While the Bears might have seen Davidson’s footage of Gayle as boorish, he and CBS understood it to be of importance to the Chicago sports fan – and hardly an invasion of privacy. It didn’t hurt that Davidson cultivated a reputation in Chicago as well as in cities and stadiums around the country as easy going, even-tempered, authentically decent man who was quick with a quip.

Over 15 years later, Davidson tore his own meniscus covering the Bears when he got barreled by former Houston Texans quarterback David Carr behind the goal post after he was sacked in his own end zone. “The workmen’s comp lady asked me, were there any witnesses,” Davidson said. “Well, there were 60,00 people in the stands and several million watching at home.”

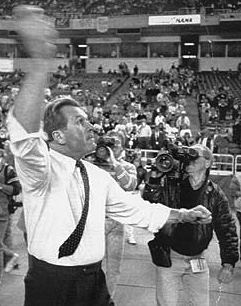

Davidson (right) with local cameraman Larry Collins. Photo Courtesy of Chuck Davidson.

Davidson spent nearly 30 years covering the Bears and still shares fond memories of the franchise, especially the ‘85 rendition. He traveled to cover the team in Goteborg, Sweden, for a 1988 preseason game against the Minnesota Vikings — the first ever NFL contest held in continental Europe. And then again almost ten years later, Davidson journeyed to Dublin, Ireland’s Croke Park to shoot their 1997 exhibition game.

The long-time face of the Bears, NFL Hall of Famer Walter Payton, who still is second all-time in rushing yards in league history, knew Davidson. Payton even goofed around with Davidson when he did a TV stint with CBS during his post-“Sweetness” days.

And Davidson could tell “a million Mike Ditka stories.” Yet, a different Chicago sports franchise and its best player ended up occupying much of his time behind the camera.

Davidson filming Bears coach Mike Ditka. Photo Courtesy of Chuck Davidson.

Davidson sat cross-legged on the baseline underneath the basket for nearly every Bulls home game — at least during the second half of the regular season — and all of their playoff games during Jordan’s Chicago career and the entire ‘90s Bulls dynasty.

He shot footage for highlights, but he also spent whole games isolated on only one or two players for CBS specials. His footage helped bring everything from intimate bench interactions to visceral player reactions into the homes of countless CBS news watchers.

“We weren’t even necessarily following just the games back then,” Davidson said. “We were shooting specials like crazy, isolated on Michael or on the bench.”

Davidson’s lens regularly captured those moments few others saw. “He really knew the games, and he could talk sports endlessly because he knew everything that was going on,” King said. “He had a knack for knowing what to shoot.”

CBS and other television news stations were often afforded premium access, especially in Jordan’s early days. On top of that, Chicago TV news channels threw money around like it was nothing in the late 1980s and early 1990s during a ratings battle between ABC, CBS and NBC.

Davidson and some of his CBS crew flew around the country with the Bulls on a five-game road trip during the ‘87-‘88 season. Their head coach, Doug Collins, allowed Davidson to film halftime locker room speeches, capture Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant lounging in their hotel room as rookies and to stand over Jordan’s shoulder as he took his teammates’ money playing cards on the team bus — even signaling to the ever-present cameraman when he was about to win a hand.

That same trip, Davidson filmed the Bulls’ lead assistant coach and World War II veteran Johnny Bach from inside the cockpit as he flew a seaplane on an off day in Seattle.

The very next season Davidson sat courtside and filmed Game 5 of the 1989 Eastern Conference First Round in Cleveland against the Cavaliers. He documented Craig Ehlo score the go-ahead basket at the opposite end directly before capturing Jordan score the now-historic series-winning shot as time expired.

In 1991, when the Bulls won the team’s first NBA championship – defeating the Los Angeles Lakers – Davidson filmed while his CBS crew interviewed the victorious players from inside their locker room at the Forum in Inglewood, California. The CBS team made their way inside the Bulls post-game celebration well before most of their nightly news counterparts. “Guys were pulling cable for me, and it’s all live back to Chicago, which was a huge feat back then for a post-game locker room setting,” Davidson said.

Unlike the Bears, who only play eight times a year at home for three hours, Davidson racked up hours of overtime shooting the Bulls. At a minimum, the cameraman shot nearly every one of the team’s 41 home games. He even developed back problems from sitting courtside for hours with a far-from lightweight video camera on his shoulder.

The Bulls consumed his working life for over a decade, from the start of the regular season in early November into late June when they went deep into the playoffs, which happened with regularity then.

After Jordan, the one-topic coverage and the intensity surrounding Chicago nightly news slowly faded. “I still had a lot of that competitive fire even at the end of my career, but the dog-eat-dog mentality had really softened,” Davidson said. “It became more of a camaraderie even between the camera guys.”

But Davidson’s work extended beyond Chicago sports. He also spent weeks traveling abroad for work, covering the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway and then four years later in Nagano, Japan.

Although the first half of Davidson’s Chicago career overlapped with some of the most significant and memorable American professional teams of all time, the cameraman also recorded much of the next generation of Chicago sports.

In 2012, Davidson raced to shoot the Bulls next superstar, Derrick Rose, the team’s only league MVP other than Jordan, as he was helped off the court towards the locker room after he tore his ACL.

Davidson timed out his retirement for mid-July 2015 just in case the Blackhawks were able to win their third Stanley Cup in five years, and sure enough, they did. He was on the ice to shoot the team during their post-game celebration and cup ceremony, as he had for the two previous championships, just weeks before last day on the job.

He adapted to the constant changes in technology throughout his career – from the early days shooting in black and white where he often measured out exact distances in order to capture clearly focused video to the more recent years of massive shoulder-mounted high-definition cameras with dozens of buttons.

“The old stuff looks like it’s coming from Mars,” Davidson said.

The lifelong union worker made a fine living, but he understands that today one person might be asked to produce the minute-long nightly news sports package, which once required three to four people.

In big markets with thriving professional teams, the sports videographer isn’t on the outs just yet. Luckily for Chicago sports fans, Davidson “pretty much taught every sports cameraman in Chicago what to do,” according to CBS Sports Executive Producer Krista Ruch who worked with Davidson for many years.

Davidson never took for granted that he thrived professionally in big markets during periods of sporting excellence, covering teams that still are spoken about in a national context today. And the thought of somehow becoming jaded by it all would seem a sweat-inducing nightmare.

Now, in his early 70s, Davidson, who saved every press pass he ever received, conjures up memories from even the earliest days of his career as if they happened only hours previously.

“I always thought we had great jobs because we got to be at important places, with important people, at important times,” Davidson said. “Every day was different. And you never knew what’s going to transpire and what kind of things were going to happen to change your day from morning to night.”

Photo courtesy of Chuck Davidson.

Although he is no longer required to stay abreast to the industry he lovingly yet meticulously followed for almost his entire life, to this day he can talk sports for hours and is fascinated and enamored with professional athletes.

Yet, Davidson is also a star in his own right.

His career ended nearly two years ago, but people in the business want to know, “how’s Chuck?”

“Everybody [athletes] knows him by name,” Ruch said. “It doesn’t really happen like that anymore.”

Davidson will perhaps always try to figure out a way to keep up with the Cubs game most places he goes. But these days, he is once again an enthusiastic lover of youth sports.

The dedicated father, grandfather and husband to Charlette, whom he has been married to for over 50 years, now spends more time volunteering during the local youth basketball season than following the Chicago Bulls everywhere they go.

As an assistant coach, for the team his son coaches, Davidson warms up little league ballplayers and lines the field for one of his grandson’s Chicago White Sox-sponsored, Naperville youth baseball team. “He’s like me when I was a kid,” Davidson boasts of his grandson. “He’s a baseball nerd. And in a way, he mirrors my youth.”

His story chasing days concluded, but Davidson’s zeal for games he learned to love in Chicago and honed as a kid in Iowa are far from reaching a climax. And just like Davidson recounts vivid details from decades ago, those whose lives he entered big and small, even from behind a lens, rarely forget.

Four or five years ago, Jordan and one of Davidson’s former long-time producers were reminiscing about the glory days of the early ‘90s when the beloved cameraman’s name came up. Almost 20 years removed from jokily yelling at the videographer who captured his whole Chicago career for hiding behind a cactus, the billion-dollar man called Davidson for a quick, friendly chat.

“If Michael Jordan passed him on the street tomorrow, he would say, ’Hey, Chuck. What’s going on?’” Ruch said.

Perhaps with a few light-hearted expletives thrown in for good measure, because “Chuck was more than just a cameraman.”

Header photo courtesy of Chuck Davidson

NO COMMENT