Not a good friend. Not a good daughter. Not a good student. Not enough. Never enough. I’m never enough.

It is thoughts like these, of self doubt, that stream endlessly and unexpectedly through the minds of Gracie Covarrubias, Ashley Renteria, and Tatiana Delgado – all Latina, all first generation college students, all struggling with a difficult reality. What they feel is not a physical ailment, but sometimes the symptoms can take on that effect. It is why they are forced to return to waiting rooms time and time again, to write their name on wooden clipboards so that a therapist can work to relieve some of their internal struggle.

Depression and anxiety can be an incapacitation of the mind. It is a debilitating mechanism that overrides their busy schedules, but who has time for a counseling session when you have a chemistry test tomorrow that could determine your eligibility for medical school? When it is on your shoulders to bear fruit to the sacrifices that your parents made in your honor years before you were even conceived? And you know they’ll never quite say they’re disappointed in you, but there’s this fear of failure that says that they are never to know just how hard it is.

Today, classrooms will fill with students in DePaul’s Lincoln Park Campus, the four college walls surrounding them caging some of them in. Today, they have given up the coolness of the autumn breeze and replaced it with the warmth multiple bodies produce when enclosed in a tight space for an hour and a half stretched into what seems like eternity, elbows touching every so often followed by mumbled apologies. All students face the whiteboard; some listen half-heartedly to the lesson as they fight the weight of their own eyelids, a heightened level of stress having kept them up against their own will for several nights now. Some battle their own demons in silence masked by smiles and laughter, not knowing that perhaps, the person sitting five seats over or maybe even just one, is having the same problem since, more than 75 percent of all mental health conditions begin before the age of 24, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“Raise your hand if you’ve ever experienced guilt because of your parents.”

The room grows quiet as hands go up from left to right, until every arm is in the air. A room full of 15 Latinas, some first generation, who have each accomplished so much, and yet, they are not satisfied with the results.

College is not an institution for which most of them were prepared.

In Rooms Just Like Mine

“There’s a lot of pressure being a first generation student because you have to get everything right. There’s a lot of people that come to college and they are like this is my time to ‘explore’ and make mistakes and learn and I’m just like, I cannot make a single mistake. I cannot screw up. Everything is on the line. You set your goals and you do anything and everything to achieve them and so there is zero margin for error,” said Gracie Covarrubias, a first-generation senior at DePaul University.

Covarrubias is not alone. For the 2011-12 school year the National Center for Education reported that 34 percent of the student body in higher education institutions was made up of first-generation college students, those whose parents have not earned a four-year degree, and they’re facing unique psychological challenges.

“It’s rough knowing that my parents can’t help me,” said Ashley Renteria, a DePaul graduate who received a Bachelor’s in health science with a concentration in bioscience and a focus in medicine. She is up to be the first doctor in her family in a system that she feels works against her.

“I failed two courses my freshman year. I could not necessarily cope with it, knowing that I had possibly ruined my shot at making my family proud,” she said.

Renteria returned to a pre-existing state of depression and anxiety shortly after.

She shut down and no longer cared about anything, She didn’t care about failing or graduating. She didn’t care to connect with people. She just lay in bed watching T.V. She forgot about eating and interacting. She cried when the anxiety hit, screaming and lashing out at people she knew were not at fault.

Covarrubias described her experience like a drop of bad thoughts that quickly turned into a waterfall of awful things. The usual hyperactive persona that everyone knew was disappearing beneath a lifeless body that had no motivation.

As a Latina in higher education, this is not a new phenomenon. The Higher Education Policy Institute says mental health problems among university students are an increasing problem. While there is limited research on the number of Latinos specifically affected in higher education institutions, it is recognized that 15.9 percent of Latino adults reported suffering from mental illness in 2011, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. But, as is the case with the general population, thousands often go without professional help.

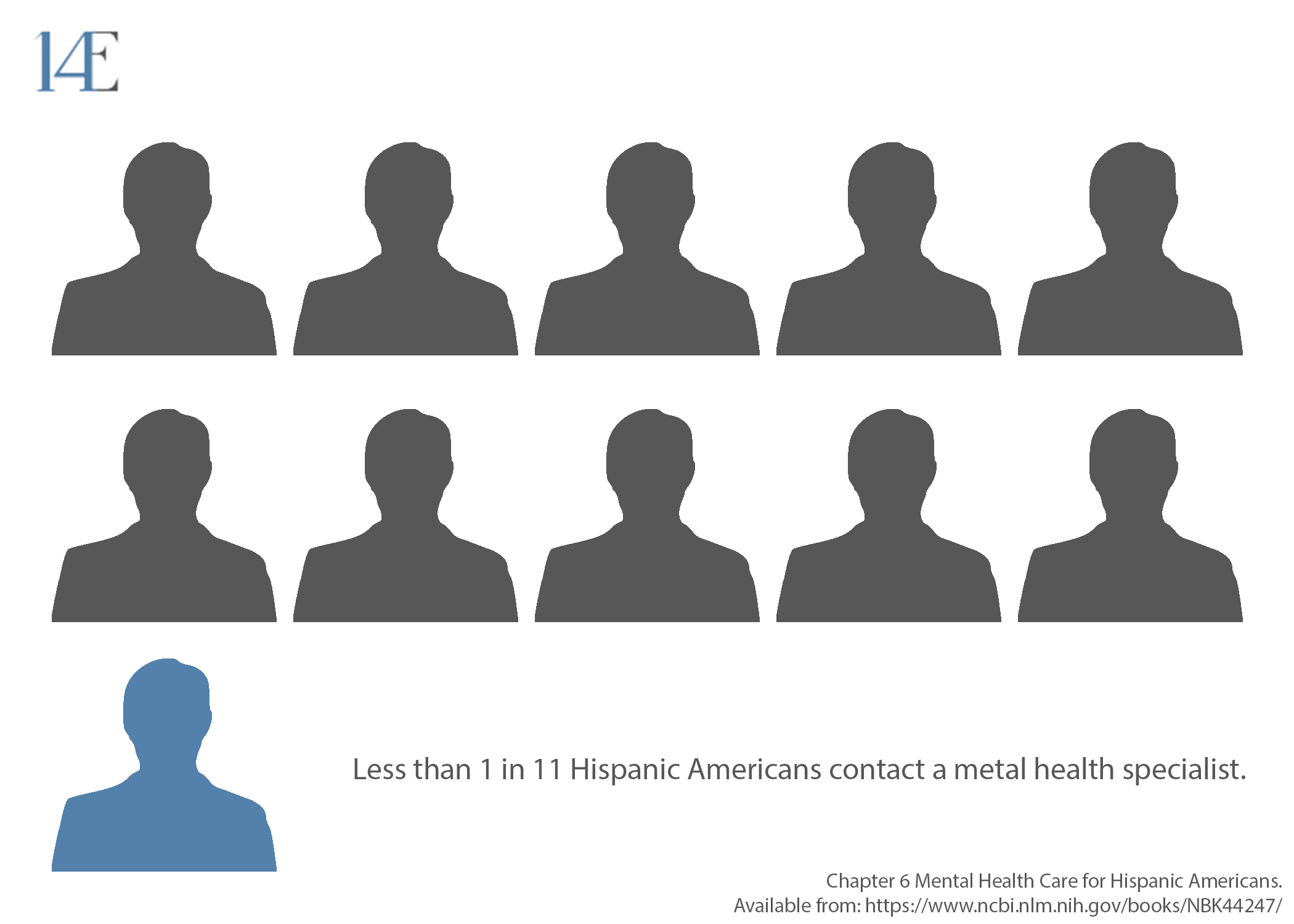

Visuals by Cody Corrall, 14 EastDespite being at high risk for depression, substance abuse and anxiety, fewer than 1 In 11 Hispanic Americans contact a mental health specialist and less than 1 in 5 contact a general health care provider, according to the American Psychiatric Association’s Office of Minority and National Affairs. (The numbers decrease further if they are Hispanic immigrants.)

“I feel like people don’t actually see it as an illness,” said Renteria. “It’s all in our head, so you can only explain it as you feel it and if they don’t feel it then they feel like it’s not there. So, they’ll look at it like you’re making it up, like it’s all in your head, like you can just change it if you just change your attitude but that’s not how it works.”

Mental health has many layers, which in some cases can be hidden very well when you have to fulfill various roles throughout the day – a student, an employee, a leader.

“You don’t have time to think about how much everything sucks and when you do, when you have those five minutes before you go to bed it’s like, you have those five minutes to lose your mind and then you have to go to bed and start all over again,” said Covarrubias. “That definitely caught up to me.”

On the outside however, both women seemed to excel. Both women joined and accepted leadership roles within their respective sororities, they became heads of organizations and departments on campus, they were and continue to be the epitome of involvement — they hide their secret well.

“The only reason I survived that time in my life was because I felt this need to please my parents and my friends. So I was on and then I was off,” said Covarrubias.

At Pilsen Wellness Center, which has 14 locations in the Chicago area, bilingual therapist Lucero Garibay said that for individuals whose culture plays a large role in their lives, this response to external stressors is very real.

“You have to be successful because for us going to school and getting an education is a family dream,” said Garibay. “It’s not an individual dream and I don’t want to speak for everybody because that’s not everybody’s case but you see that a lot with the population. And then with your friends you want to be like, ‘oh yeah, I’m hustling all the time. I’m doing all these great things’ which is great that we have goals and stuff but, it’s very easy for us to forget that we are humans too and it’s okay to not be okay and to accept that and to be willing to talk about it.”

Conversation around mental health in Latino households, however, remains relatively low. In fact, the 2003 article “Barriers to Community Mental Health Services for Latinos: Treatment Considerations” found that there is a difference that exists among Latinos when dealing with mental health. Youth and adults deal with distinctive stressors. Older Latinos grow overwhelmed when their values and beliefs do not align with those of the “host country,” while Latino youth have been found to experience emotional instability because they are forced to rapidly adapt while simultaneously enduring injustices such as inequality, poverty and discrimination.

According to the World Health Organization, poor mental health can also be associated with “rapid social change, stressful work conditions, social exclusion, unhealthy lifestyles, risks of violence, physical ill-health and human rights violations.”

Latino youth thus enter into a sense of “double consciousness” in which they make themselves believe that their parents cannot possibly understand.

“There’s just this idea of not taking whatever is going on with you outside of the family,” said Garibay. She related this reluctance to the strong sense of familismo present in Latino households, which places a high value on saving face for the benefit of the family.

“There’s this stigma that, oh you know if you go to see a therapist you must be crazy or you must be wanting to kill yourself if you’re going there, which isn’t really true,” she said.

A lack of dialogue however, is only one of the barriers this population faces when dealing with mental health. The challenges when dealing with this population are a handful: the downplaying of symptoms as being “dramatic” or an “attention seeker,” a lack of education that leads to a misdiagnosis where people treat physical manifestations of a psychological problem instead of addressing the root of the cause. The fear of stigmatization, the association between therapy psychiatrists and insanity and a lack of financial stability are some factors.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 21 percent of Hispanics/Latinos under the age of 65 do not have health insurance coverage as of 2015.

The problem is oftentimes mistaken as temporary and if it is recognized, Latinos will rely not on professionals but on their pillars of support: family, community, traditional healers, or churches. Mental health problems, however, cannot simply be prayed away.

“You know being a minority they feel like its not a thing, that it’s just attitude issues that I have to work through but, after seeing me ask for help multiple times over the years, begging them for help, they’re starting to comprehend,” said Renteria.

Renteria is not the only one that struggled to bring attention to her negative state of mental health. Tatiana Delgado, a student majoring in psychology with a concentration in human development, did not share her condition until she found herself in a hospital emergency room.

For Delgado, the time lapse between her freshman year when she realized she was mentally unstable and her junior year when she actually sought treatment proved to be detrimental.

“It just kind of got worse and worse where eventually I was having thoughts of suicide because it was so much pressure,” she said.

“I would wake up and I would be like, I don’t want to get up. I don’t want to say hi to people. I don’t want to have to sit there while someone talks to me. I’m not even going to remember it because my heads going to be somewhere else and so, I got to the point where I was like, what’s the point of doing anything?” said Delgado. “These thoughts led to, ‘I don’t want to be alive’ or like, ‘nobody is going to really care about me if I die and that led to me thinking, I should really just off with myself.’ I guess that’s how it went from not smiling to wanting to die,” she said.

Today she openly shares that she suffers from four mental disorders: anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dissociative identity disorder, which used to be known as multiple personality disorder.

It is coincidentally not helpful that, less than 25% of mental health professionals are minorities as stated by the American Psychological Association. At the same time, other professionals are not culturally trained and their lack of multilingualism limits their ability to help.

“If a lot of the reasons they’re not going is because they don’t see that representation, that’s very real, and you really can’t blame them for that because they want their experiences to be heard and relatable,” said Garibay.

It is this very dilemma that prompted Dior Vargas, a Latina feminist, mental health activist and suicide attempt survivor to develop her People of Color and mental illness photo project.

“There are tons of articles that list people with depression and other mental illnesses but you rarely see someone who looks like you. We need to change the way this is represented. This is not something to be ashamed about. We need to confront and end the stigma. This is a NOT a white person’s disease. This is a reality for so many people in our community,” she writes in the introduction to the project.

Together, a group of eight students working with the campaign To Change Direction developed what they called Tough to be Tough. The self-designed project aimed to raise awareness for the five signs of emotional suffering: poor self care, personality change, withdrawal, agitation and hopelessness on campus.While it is evident that a blanket of silence still covers this sensitive topic, DePaul University took on an initiative to bring awareness and advocacy to this issue. A public relations campaign known as Bateman was given the task of de-stigmatizing mental health with a specific focus on minority communities.

“You know a lot of college students don’t like to talk about it and specifically with our target audience they don’t really have an opportunity to talk about mental health, whether it’s mental barriers or religious barriers,” said Sydney Bickel, one of the contributing members of the campaign. “So, we really want to focus on allowing students to feel comfortable talking about mental health and mental well being.”

DePaul’s attempt was in direct contrast to the states downsizing of mental health services. Currently, the state of Illinois ranks among the highest when it comes to the cutting of mental health programs.

According to the National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI), between 2009 and 2012 the state cut $113.7 million in funding related to mental health services. It has closed two inpatient facilities; six Chicago mental health clinics and various community mental health agencies. The report by NAMI also calculated that there was a 19 percent increase in emergency room visits for people in the general population experiencing psychiatric crisis between 2009 and 2012.

A lack of resources, primarily in communities of color, create a direct pipeline from the home, to the streets, to the Chicago county jail which is now the largest mental health institute in the city. In 2014, police responded to about 22,000 mental-health crisis calls, according to the Chicago’s Office of Emergency Management and Communications – 44 percent of those calls from predominantly black districts, 30 percent from Latino districts, and the remaining 26 percent from white districts. According to this same office, seven of the ten districts with the most mental health related calls came from the South and West side, communities that are predominantly African American and Latino.

“It’s nothing new unfortunately,” said Garibay. “I think the place that we’re at today with awareness and lowering that stigma we’re taking steps to get there but we’re not quite where we should be.”

Dissuading a population from associating insanity with the search of a positive state of mental health thus becomes the million dollar questions. The answer, according to Garibay, is “to really just keep having the conversation.”

“Community awareness and advocacy are something that we need to keep working on, working more so in prevention than just intervention. They’re both equally important,” she said.

For Covarrubias, Renteria and Delgado, that is exactly what they hope to achieve by sharing their experiences — to open a stream of dialogue and put a recognizable face to mental illness.

“I really needed someone to say, ‘it’s going to be okay,’” said Covarrubias. “To say, ‘it is awful right now and it’s probably going to suck for a lot longer but there will be a day that you wake up and it’s not going to hurt as bad, and there’s going to be days where it’s going to be a little of a relapse into this bad day syndrome, but it’s going to be okay because you have the tools to move past this and you’re strong enough. You’ve conquered this before and you’ll conquer it again.’”

Header photo courtesy of Mirlinda Elmazi.

The Soccer Player in the Closet Attempts to Wrestle with Queerness and Depression in Latinx Communities – Fourteen East

1 March

[…] it didn’t identify any new methods of destigmatizing mental health in the Latinx community. Instead, it uses brujeria as a running gag to rid the apartment of Cristiano’s lingering spirit […]