After giving birth to her second child in September 2016 — a baby girl named McKenzie, born five weeks premature but otherwise healthy — Jody Thomas felt her long-held strength finally begin to unravel.

The Chicago-area mother had been through this process before. Her first daughter, born in 2011, died suddenly at just six months old, leaving her devastated but unable to talk about her grief.

“I blocked off my emotions,” Thomas said. “I never grieved properly for her.”

But as she made her daily visits to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where McKenzie was being treated, Thomas found herself gripped by feelings of intense sadness: crying jags, loneliness and a sense of impermeable guilt, like she was unworthy of being a mother. “The feelings just came out,” she said. “And they really came out.” Worse, she had no idea how to seek treatment.

A keen-eyed nurse took note and pulled her aside. Have you considered that you may have postpartum depression? she asked, and handed her a card with the contact information for a therapist working at the postpartum depression treatment program at a Healthcare Alternative Systems (HAS) clinic. Thomas has been a patient ever since.

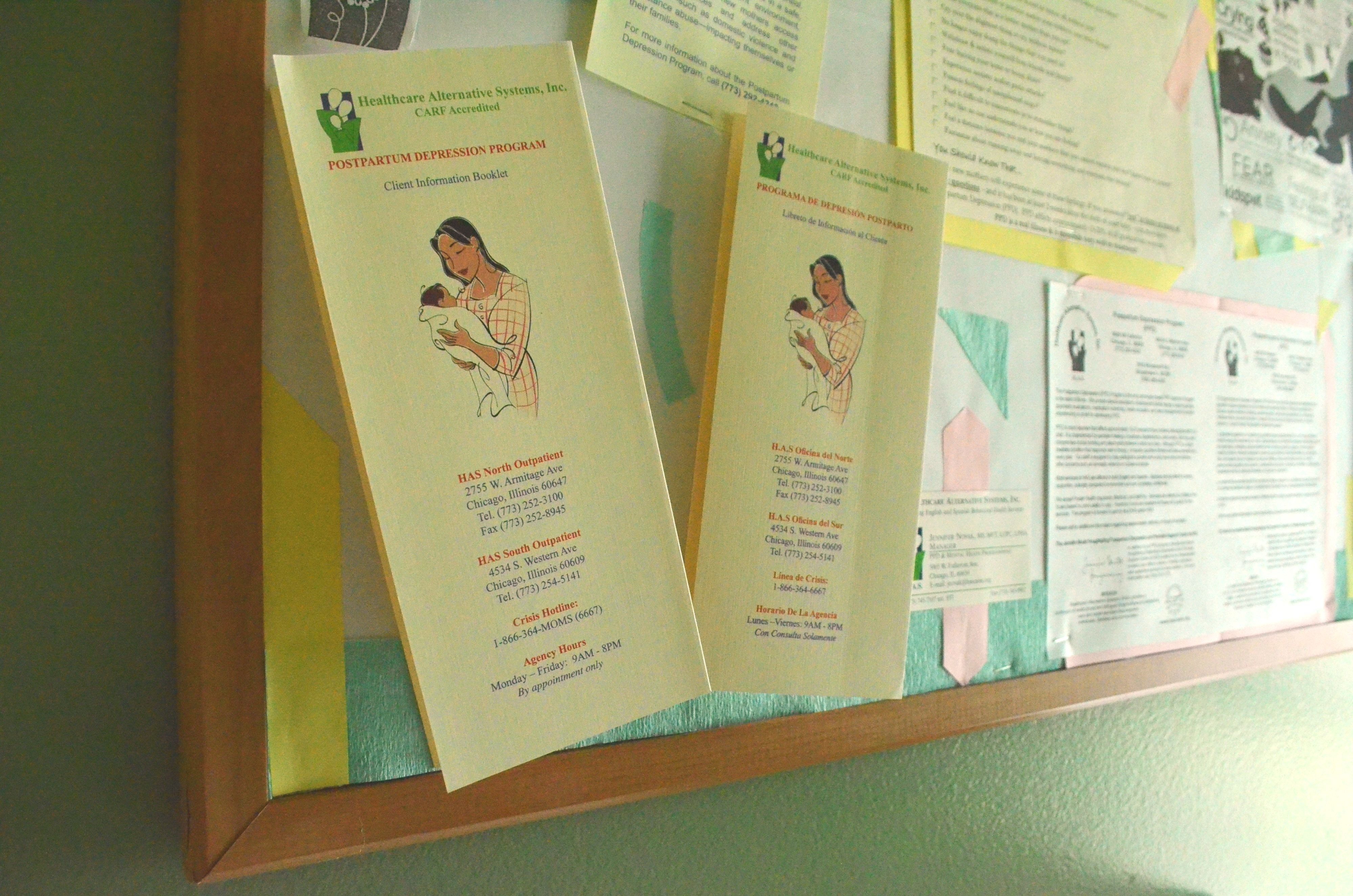

The HAS postpartum depression treatment program — operated out of three clinics on the South and Northwest Sides, as well as one in the western suburb Broadview — offers therapy, psychiatric evaluations, medication monitoring and health education to more than 1,000 pregnant and postpartum women like Thomas each year. Unlike most postpartum depression (PPD) programs, which are located in-house at hospitals, HAS utilizes a community-based treatment model: the only program of its kind in Illinois, designed to treat women within their own neighborhoods.

“We try to engage the community in a way that is meaningful to the participants that we’re serving,” said Jennifer Novak, the program’s director. “That means being present in the community and being aware of what resources are available in the community.

HAS’s Belmont Cragin clinic at 5005 W. Fullerton Ave (Emma Krupp, 14 East)

As the name suggests, a community-based treatment model focuses on tailoring treatment to meet specific community needs, taking mental health care beyond its medical context to ensure each patient receives care that feels relevant to her life. For HAS, which primarily services women in Latinx and low-income communities, this ranges from outreach to bilingual treatment and referrals to other neighborhood resources, like support groups and case management services.

“We have tons of places we can refer them to — different groups, support groups where you meet at the library or walking moms groups,” Novak said. “Just things to get her out of the house and get her engaged.”

Healthcare Alternative Systems provides behavioral health services to people in Chicago and surrounding areas, particularly those in Latinx communities. Its PPD program was founded 13 years ago, when the Illinois Department of Human Services (DHS) put out a statewide call for grant proposals related to the treatment of postpartum depression. At the time, PPD had become prominent in public health discourse in the early to mid-2000s after a series of well-publicized postpartum suicides in the Chicagoland area and the release of Brooke Shields’s memoir “Down Came the Rain: My Journey Through Postpartum Depression.”

The disorder remains pervasive more than a decade later, with around one in seven childbearing women experiencing full-blown PPD within her lifetime. Some studies have found that rates double for low-income women, who are more likely to suffer from external stressors that lead to a history of depression — the largest risk factor for experiencing PPD.

Thanks to the DHS grant, HAS is able to offer hardship assistance to all women who come in seeking treatment without insurance, including those who are undocumented. This usually pays the full cost of their coverage, with a sliding scale payment option for those who can afford it.

“I think, for a lot of moms, it’s empowering to be able to say, ‘This is what I’m contributing to my therapy and my treatment,’ even if it is only $5 or $10 a session,” said Stefani Godina, the program’s senior therapist. “For some of the moms that can’t even do that, we try to work with them and say, ‘You’re eligible for the grant, don’t worry about it.’ We want them to focus on treatment rather than the financial aspect of it, and we try to do that as best as we can.”

Per its community-based model, HAS also pays attention to, as Novak puts it, “how different cultures approach treatment,” or the ways in which each woman’s community and upbringing affect her experiences with PPD. Undocumented women, for instance — many of whom left behind their support networks to live in the U.S. — often suffer from extreme feelings of isolation that contribute to PPD. The program’s therapists, all of whom are fluent in Spanish, attempt to bolster their social support system by working with family members and recommending community groups for them to join and meet other mothers.

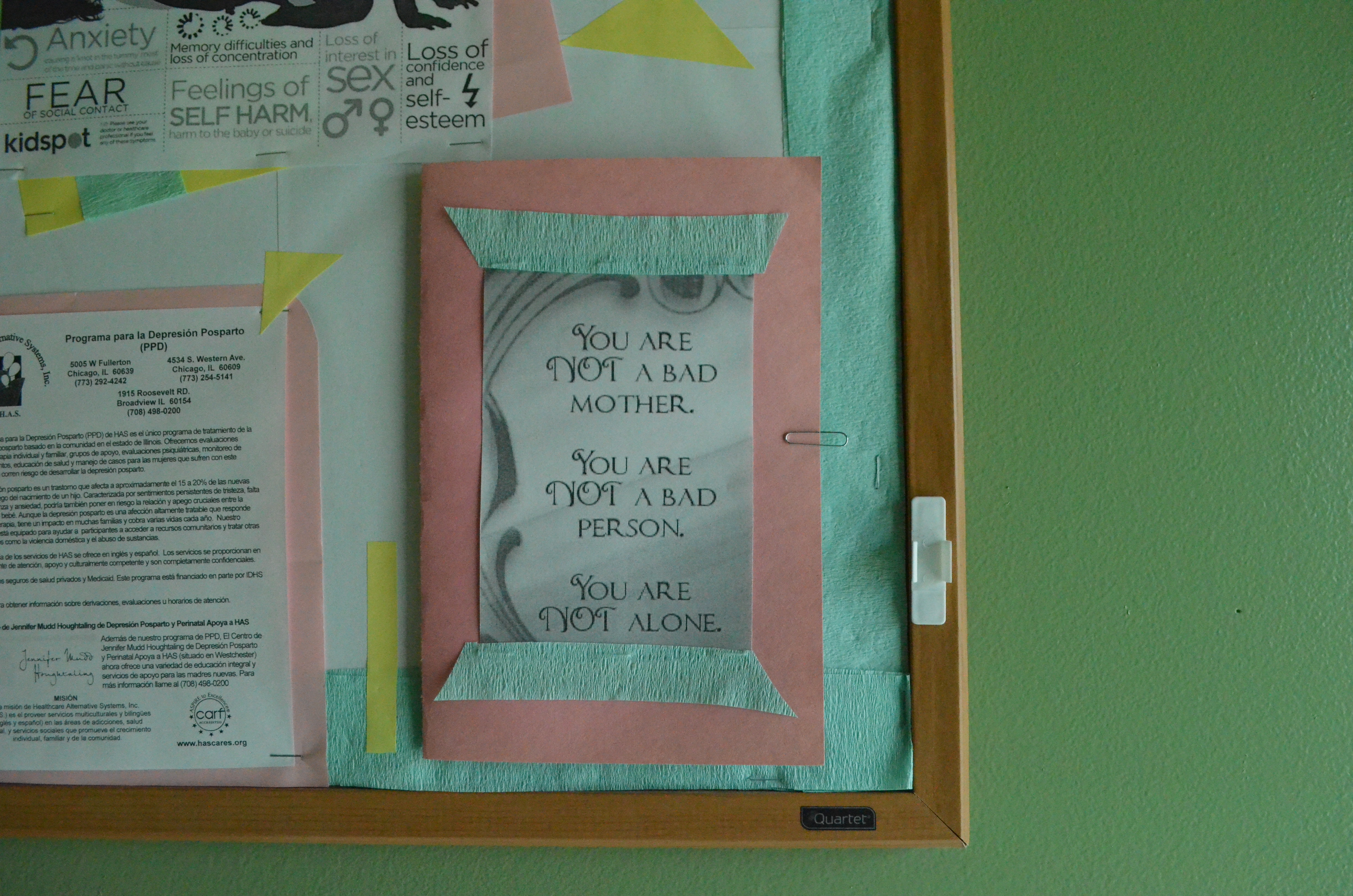

Though each woman’s treatment plan may differ based on her needs and background, staff say women often come in with a sense of guilt about their condition. The idea of an unhappy mother — one who might not bond with her child immediately or feel the unconditional love one is “supposed” to feel upon giving birth — is anathema to the cultural mythology of motherhood, which tells women that the postnatal period is meant to be the happiest time of their lives. Therapists aim to mitigate these concerns, and normalize PPD as a valid stage of the perinatal experience.

“We want to help them understand that it’s a very real disorder, and it’s a very treatable disorder,” Novak said. “It does not mean they’re crazy.”

A bulletin board providing information and pamphlets on the clinic’s PPD program (Emma Krupp, 14 East)

Yet with only four locations in the Chicagoland area, the HAS PPD program can only provide services to so many Illinois women. Talks to expand the program statewide, which Novak says DHS once expressed interest in, have largely fizzled. Patients often travel from suburbs like Skokie and Plainfield, and some spend hours in transit just to get treatment.

“Some people come from so far,” Novak said. “I can’t even wrap my mind around how far they’re coming to get here.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention writes that “most” women, even those with severe forms of depression, see improvement in their symptoms upon seeking treatment. An average HAS patient spends around six to nine months in the program, though there’s no cap on how long they can continue to receive treatment. Improvement manifests in a myriad of small ways — a mother’s personal hygiene improves, or she’s no longer weepy during therapy sessions. Sometimes, therapists say, it’s helpful for patients just to receive the initial diagnosis.

“It is very liberating for them to call it something — like, this is postpartum depression, meaning that there is a start period and an end period,” Godina said. “We want them to look at it as an adjustment, and then that’s how we gear therapy. It’s about adjusting to this new life change, and you’re not going to be this way forever.”

Thomas, who is approaching the one-year anniversary of her first appointment at HAS, understands the power of naming the disorder. She says she’s seen vast improvements in her mood and outlook, leaving her able to focus on her relationship with McKenzie.

“It’s been a tremendous help for me and my family,” Thomas said. “I felt better because I knew that it wasn’t my fault, and that it wasn’t me doing it on purpose. It was just something that I could put a name to.”

WHERE TO FIND HELP

If you or someone you know needs help, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or visit www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Healthcare Alternative Systems, 773-252-3100, http://www.hascares.org/contact-us/

Postpartum Support International, 800-944-4773, www.postpartum.net

Header image by Emma Krupp

NO COMMENT