On a cool spring day in 2014, reports of security breaches in the credit card processing databases at Michael’s craft stores and the Home Depot fomented. As a frequent customer of both suppliers who preferred plastic payments to paper, I received an invitation to join a class action lawsuit against the home improvement giant. In March 2017, Home Depot agreed to a $25 million settlement to offset the damages incurred by more than 50 million customers, which leaves me wondering if I should have responded to the request.

This was just the beginning. In last four years, hackers successfully infiltrated networks at Target, Yahoo, Sony, Uber, the Office of Personnel Management, Anthem Blue Cross, JP Morgan Chase and dozens of others. The stolen information hemorrhaged onto the dark web, where caches of email addresses, credit cards, social security numbers, and other sensitive pieces of information trade at prices virtually any consumer can afford. The digital assault reached an apex this September when consumer credit reporting agency Equifax announced a ubiquitous breach of personal information that may affect up to 143 million Americans, including you.

A day after the Equifax breach, I received an email from DePaul with resources for monitoring the incident’s impact on my personal information’s security. Needless to say, I was more proactive than before. Following links to Equifax’s website, users find a portal where they enter their last name and six digits of their social security number to obtain the status of their information.

As it turns out, I’m in the clear. My personal information wasn’t nicked, but what about everyone else? Why should we have to trust Equifax with our intimates again? From a customer’s perspective, I wouldn’t say my relationship with the credit-monitoring agency was completely consensual so much as a requirement. Even though these high profile breaches are becoming more and more prolific, they’re merely mountain goats on top of a garbage pile.

While the internet could be the greatest achievement of our lifetime, it could also be a total disaster. Security breaches aside, we leave millions of details about our lives, habits, fantasies, medical history, tabled perversions and obsession with celebrity gossip in picture-list form on remote servers across the world. What would happen if someone gathered all this information together? What would they see? What’s your digital identity in a world of anonymity, and are there ways to protect it?

What We Give

Between lambasting the government and Googling ways to lock down my credit information, I toggle between Facebook, Gmail, Amazon and scads of sites that I voluntarily leave breadcrumbs on. For a complete look at our digital facsimile, we must consider the information we offer freely as well as the data we protect. Both are equally telling and attract the attention of strangers lurking online.

From the places we frequent to the arbitrary misclick, websites store small bits of textual information called cookies on a visitor’s computer. Cookies help websites identify patrons and tailor pages to meet an individual’s preferences. From a benevolent stance, cookies serve the user. However, cookies can also track a person’s browsing habits, and marketing firms are quick to sweep up the crumbs.

When we navigate the web, promotions cater to our individual tastes because advertisers are watching us. It’s called behavior targeting. Our search history, wish lists, name, age, sex and location all lure today’s marketing sector. Through third party cookies, advertisers that occupy space across a network of websites can funnel ads to a surfer’s browser based on their previous traffic.

Our digital footprint goes beyond the crumbs. Whether it’s opting in to the terms and conditions of your local bank’s privacy policy,or signing up for a customer “preferred card” at a regional grocery store, we’re contributing to the massive datasets that government agencies, private businesses and curious campaigners swap in a virtual bazaar.

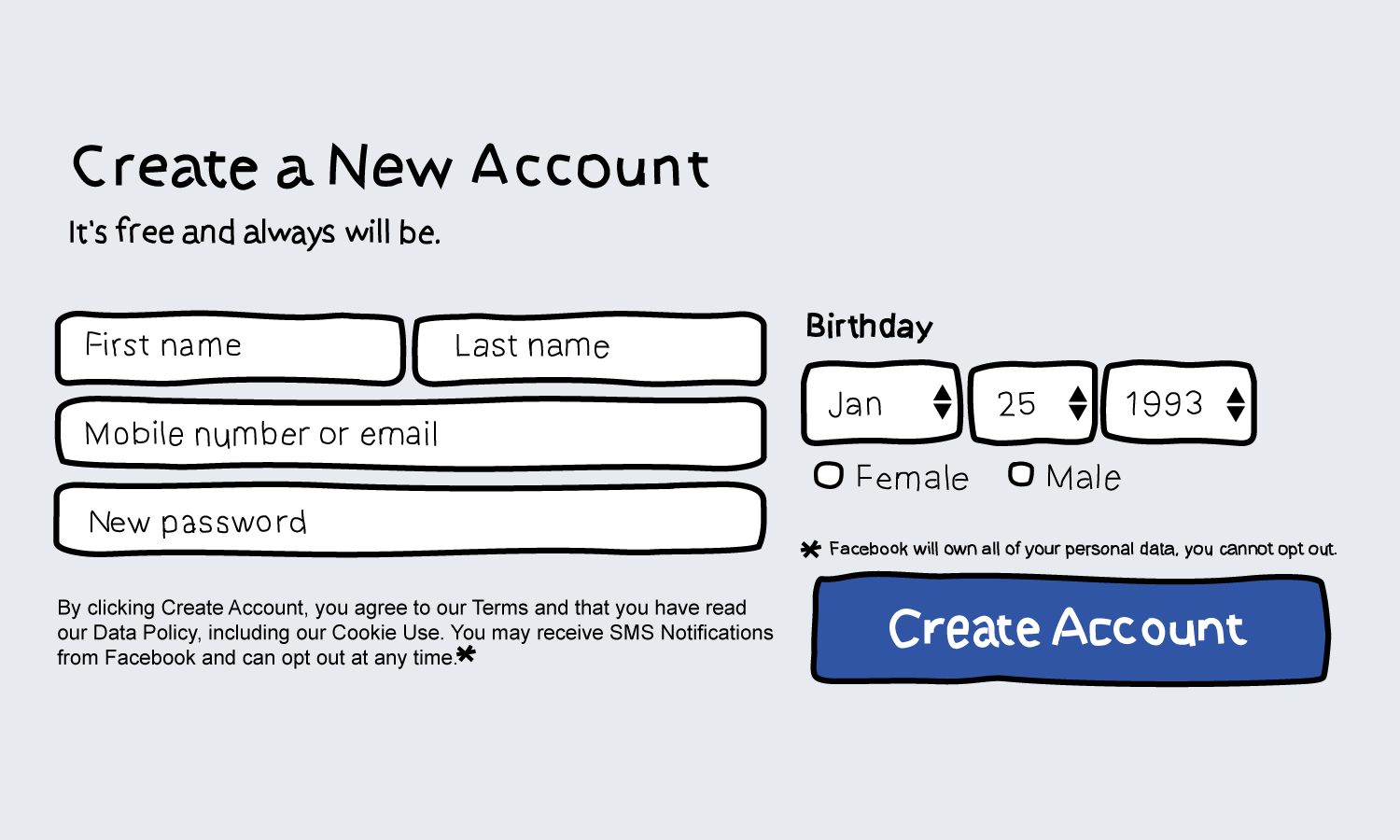

We voluntarily provide comprehensive profiles on social media outlets, dating websites, blogs and surveys. We place our trust in Mark Zuckerberg, the IAC Board of Directors, Jeff Bezos and hundreds of others to keep our computing habits discreet. But they don’t.

Issues of disclosure extend beyond the behemoths of the web. In the spring of 2016, student researchers in Denmark published the data of over 70,000 OKCupid members. While the information was already publicly available to subscribers, the researchers employed bots to compile the dataset, which left some academics questioning the project’s integrity. With the word out, it’s now possible to connect profiles with users’ real names.

This winter, OkCupid announced that it was eliminating usernames entirely. In a statement to subscribers, the matchmaker claimed it was “ time to go by the perfectly great name you already have.”

In the more covert case of cursor tracking, we don’t enter information, or have data stored on our computers; a few lines of basic JavaScript allows programmers to track the unique movements of a user’s mouse on a webpage. The roadmaps can be stored and later evaluated by analysts. Security experts have also used cursor tracking to detect identity theft; one study claimed a 95 percent success rate in identifying intruders based on mouse movement.

What List Makers Do with Your Data

Data miners pool the digital streams and construct detailed profiles of us based on our online presence. Some consumer information groups sell or trade our digital doppelgängers to anyone with a checkbook looking for access. What purchasers do with our information is entirely up to them.

As I write, Glassdoor.com has over 700 jobs listed under “data mining” in Chicago alone, many of which pay six figure salaries. These jobs will vary in where they source information (internal, external, public, private) and how they process their data in an effort to decode user patterns.

In 2014, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed a report that showed collectors had gathered billions of “data elements” from almost every U.S. consumer. The document was an effort to urge Congress to advocate for transparency on behalf of the public. It named nine aggregation companies that compile your computational confidentials.

While Chicago-based company Exact Data didn’t appear in the FTC’s 2014 report, they made it into a statement issued a year prior in which the commission cited them for violating the Fair Credit Reporting Act. According to the FTC, they were selling “pre-screened” consumer records to make credit card offers.

Isaias Rivera, an animated twenty-five-year-old from the city’s southwest suburbs, is a former Exact Data sales manager. Rivera has spent the last five years working in social media, marketing and promotions throughout the country. During his time at the direct marketing firm, he encountered colossal list sets, customized search engines and a convoluted network of accountability from every side of the industry.

Companies like Exact Data aggregate lists from a variety of sources: financial institutions (Chase, Bank of America, Fifth Third Bank, American Express), service providers (Verizon, ATT) and a handful of government agencies. After dredging up our profiles, experts predict our spending habits and classify us accordingly.

As consumers, often we allow Big Brother to monitor us. “Say you agree to your terms for an Amazon account, or your account on Walmart.com or even your Chase debit card,” Rivera explained. “They’re tracking every transaction, and it’s getting put into a category. You only have to accept it once.”

As a result, consumer information groups know most people’s shopping routines. From trips to the store to what prescription medication we’re on, the information filters into data centers. “One of my clients wanted people who bought jerky on a biweekly basis. I could find that,” Rivera recalled. “A potential client in Oklahoma was skeptical of our services, so I pulled up her last purchase at Walgreens.” He closed the sale.

It doesn’t stop with the banks or internet providers. The largest websites that offer users free services sell your information. Dealing in data metrics is standard operating procedure for your favorite search engine, music provider, ride-sharing app and dating site. Whether you’re cueing up Spotify or ordering barbeque through GrubHub, your activity is no secret.

Have They Figured Us Out?

How does this affect our daily lives? Will my FitBit betray me? Should I be skeptical about making my next purchase? Is it one I made with my own free will or was I just hustled by a next-level algorithm?

Tech journalist Stephen Baker shepherded new concerns for where consumerism, politics, health and national security were headed in the 2007 book “The Numerati.” It’s been a decade since the book’s publication, and most of the technology scientists and researchers were musing then is still tinkered with now.

Baker’s world features a shopping cart that makes suggestions to customers while curbing coupon cutters. It also highlights automated workplace efficiency programs that would assemble teams of qualified candidates for a given project and tamp down idle employees slacking on the company’s dime.

The digital prospects of the book are entirely feasible, but there’s still considerable work to be done. As scientists seek to establish a method for creating usable insights, they’re constantly bombarded with new and growing sets of data to add to the equation.

The best collection companies are the ones that regularly update and scrub their data. Often, these lists get shuffled vertically and horizontally throughout industries. The process forms a haphazard circle of old information mixing in with new, not unlike a never-ending game of telephone — only participants are trading massive rolodexes that absorb and shed entries while making their rounds.

According to Rivera, most of the players in the data collection game are just trying to make a buck by turning lists over. They purchase information to pass it on to the next buyer. Even the lists with the most “actionable” data, the kind of information that would compel a recipient to act, offer no guaranteed results for the companies who buy them.

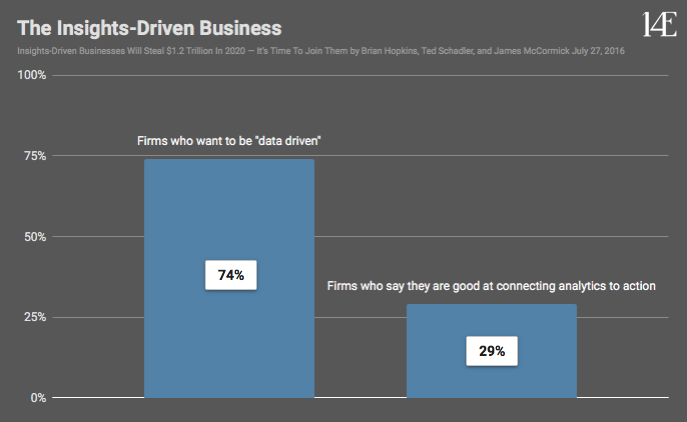

In a 2016 study published by Forrester, researcher Brian Hopkins found that, “while 74 percent of firms say they want to be ‘data-driven.’ only 29 percent said they are good at connecting analytics to action.” Are businesses really this disconnected from their customers, or do even traditional trades hope to mimic the digital efficiency of Amazon?

What They Take

In 2014, Brian Krebs published “Spam Nation,” a book that revealed the underground Russian crime syndicates responsible for two of the largest spam pharmacies. While the term may seem dated now, Krebs insists that spam is the number one way hackers hijack our computers. The term extends to “email, including missives that bundle malicious software and disguise it as a legitimate-looking attachment, as well as phishing attacks designed to steal banking credentials and other account information,” Krebs said.

Even the Target breach was the result of a malicious email sent to a heat and air conditioning vendor that did business with the retail titan. Once inside the HVAC company’s system, hackers were able to infiltrate Target’s database.

The modern-day system cyber criminals navigate is both simplistic and serpentine. In the past, only programmers and coding experts could break into a stranger’s computer. Now you can purchase user-friendly software and, for more complex jobs, just hire an expert.

While the programs are becoming easier to use, the paths they travel are twisting labyrinths, often hosted in post-soviet countries, that allow hackers to operate anonymously. The shifting web of service providers coupled with the ability to remotely commandeer IP addresses makes it difficult to trace an attacker’s origin.

Furthermore, automated systems can work together to flood websites simultaneously, making it impossible to trace an attack to a single source. These bombardments, known as denial-of-service attacks, prevent real users from accessing a site.

The sharks at the top of the food chain are after the same thing as the consumer information companies: the biggest list. The more data they have, the more they can sell.

The system’s bottom feeders can purchase portions of the large datasets or scam the old fashioned way — by telephone. Opportunists cold-call their victims and try to verbally persuade them to provide information.

Two of the biggest fish also used their network to setup a pharmaceutical scam. The fraudsters peddled counterfeit Viagra, Cialis and other medications to customers looking for discount drugs. The death of Canadian Marcia Bergeron in 2006 was attributed to medication purchased from an online pharmacy that contained uranium and lead.

What Can We Do to Protect Ourselves?

Should we all unplug now and walk away with whatever digital dignity we have left? Is it even possible? Personally, I don’t think it’s necessary, but we should all start paying more attention to how we conduct ourselves online.

First, don’t provide information unless it’s absolutely necessary. Voluntarily building profiles through professional networks, social media, retail and other digital platforms does the work for marketers and analysts. Utilize these tools intelligently and minimize your usage.

Second, master your password crafting and keep them private — not just online, but with pen and paper. If a thief gains access to your computer, they can infiltrate your documents. Come up with a formula. For example: two words of significance, second letter of each word capitalized, broken up by memorable numbers and drop a special character at end. This is a cyber article, it’s my third article this year, and it’s money ($), that gives us: cYber3aRticle$. Nasty looking, I know, but typically you don’t see it. Of course, if you’re flush with cash and looking for an easier solution, you can buy password management software.

Third, seriously consider using programs and applications that do not store your information. Apps like SnapChat and Mark Cuban’s CyberDust delete messages after review and, for encrypted correspondence, there’s WhatsApp, Wickr Me and Facebook Messenger. Techradar.com has a complete list of its top secure messaging services.

Polishing your online persona never hurts either. Take the time to regularly purge your social media contributions. You can shrink your footprint by downloading photos to your computer and deleting them from the web. While you’re at it, dump all those doge memes from 2013.

Finally, security expert Brian Krebs advocates three principles: “1. If you didn’t go looking for it, don’t install it. 2. If you installed it, update it, and 3. If you no longer need it, remove it.” It’s a simple mantra that reduces your vulnerability.

The digital futurescape of a synchronized network that can anticipate our every impulse and whim is a dystopian nightmare. The outlook echoes the premise of “Minority Report,” and one can’t help but imagine a “Fight Club” -inspired backlash where extremists destroy data centers to restore world order. But don’t worry. We’re not there yet.

While the internet can be a scary place, teeming with friends and foe, we must press on and not let profiteers stop us from buying bacon bandages and glow in the dark toilet paper. At the same time, we must protect ourselves by minimizing our footprint, opting out when possible, securing our passwords and leaving unsolicited emails and downloads closed.

Header illustration by Ally Zacek

NO COMMENT