Life before 1993 must have been weird.

What was it like? Before everything changed, I mean. Before Bill Murray reached down from the heavens (Woodstock, Illinois), blew us a kiss and disappeared, leaving us with the answers to all of life’s questions in a tight hour and forty minutes? What was life like B.G.D. — Before “Groundhog Day?”

I wouldn’t know, but I can almost feel it. In retrospect, maybe that is what makes ‘80s movies feel so alien to my generation. “Cheesy” is the word that has always come to mind to capture the peculiar innocence of films like “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” “Ghostbusters” and “Back to the Future,” but is that a mistake? What if the world B.G.D. simply didn’t know any better? What if it was just missing a savior to pull them up out of the muck of The Old Times, out of a fog of unenlightenment?

Because “Groundhog Day” is strangely familiar. Not in the obvious sense that a 25-year-old movie has become a cultural touchstone and a worn-if-brilliant premise for generations forever after to rip off. It’s the sense that, after seeing it for the first time this week (sorry about that, everyone), I felt like I grazed some ancient, inarticulable wisdom, an invisible part of the world I never thought to notice before — like the distinction between Adults™ who own briefcases and the rest of us who would, say, be charged as adults if we got caught murdering someone but aren’t totally clear on how we’re supposed to file our taxes.

For me, part of lacking that Adult™ status has been a condition of being a student, a role I’ve had since I was approximately six years old. I love school, being a college student. I love the irregularity and the stress and the thrill of genuinely having no idea what the next day will bring.

I’m also about to graduate. And even if I manage to be a lifelong learner or forever student, where the world is my classroom, I’m about to cross this threshold of adulthood. Which is scary.

This close to the end of the diving board, watching “Groundhog Day” felt a bit like a last ditch effort at finding the answers to life that adults of my childhood always seemed to have.

After “Groundhog Day” (A.G.D), I can’t help but look at unoccupied people on the street, on the CTA, in the park without headphones or cell phones or books or anything and wonder — are they thinking about it too? Are they reliving a hundred arguments? Do they see a thousand possibilities stretching out into infinity from a single choice? Are they wondering if that line from Bill Murray was improvised or written?

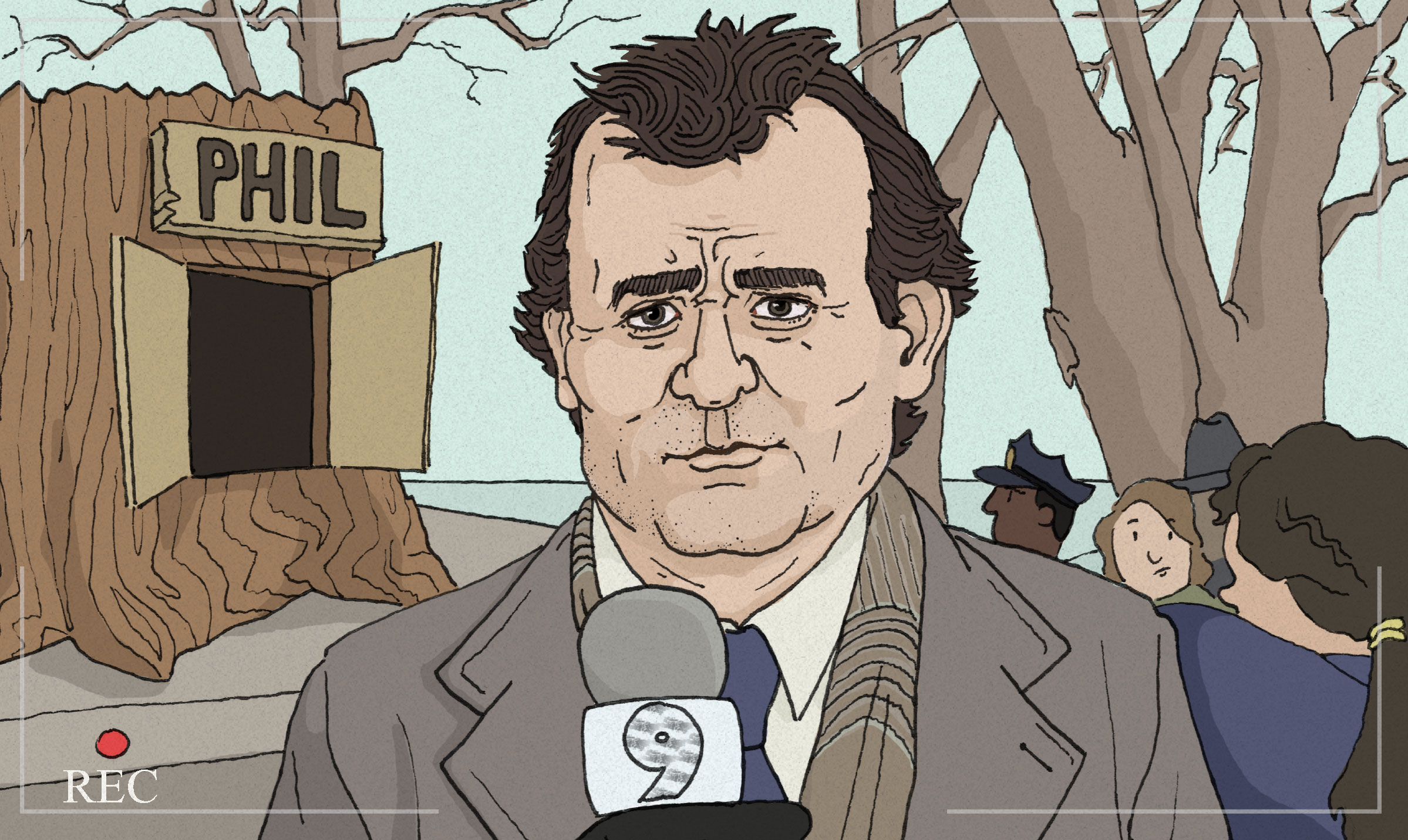

I know that most of us are not thinking about “Groundhog Day” the 1993 movie: the one where a Pittsburgh-area weatherman named Phil Connors (Bill Murray) makes a trek to Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, to report the predictions of another Phil, who happens to be a groundhog, who happens to predict the weather in “groundhogese” on the basis of whether or not he sees his shadow.

Phil the weatherman is an asshole, coincidentally, and hates practically every element presented in the previous paragraph. Human Phil is very good at his job, he assures his co-workers, because he is being courted by national TV stations. This will be the last Groundhog Day he thinks he’ll ever have to cover, since he and his big fat meteorologist brain are on a skyward path to bigger and better things.

Which is why (in the karmic, cosmic and cinematic sense) he is subsequently doomed to relive Groundhog Day for all of eternity. (For the record, we don’t actually know why Phil gets caught in the loop, although earlier versions of the script suggested it was a gypsy curse or a time wizard.) No matter the outcome of his day, he will, upon waking up, be sitting in his bed, repeating the same day, listening to “I Got You, Babe” on February 2, 1993. This premise gives way to one of the most fascinating experiments in the history of media: specific, mundane eternity in a sandbox with mile-high walls.

Watching “Groundhog Day” in 2018, I was surprised to find myself thinking of video games — specifically in the context of a sandbox. Beyond the childhood enclosure, “sandbox” today refers to a strain of video game philosophy where players are plopped into a world in which they can kind of do anything. Games like Minecraft, Garry’s Mod and the Fallout series emphasize the freedom to roam and interact with a world in 360 degrees rather than sticking players into linear, static plot. Most importantly, the greatest sandbox games give players something that almost no other form of media can — the vision of consequential choice.

Consequence, with an asterisk: consequence defined by game designers with a limited series of ones and zeroes, no matter how much freedom a player may perceive. Video games grant us the heightened illusion of control over a system, even if that control is always on someone else’s terms.

At its core, it’s the same illusion that “Groundhog Day” exposes so quickly. Control is central to Phil’s conception as a character — his entire job and worth is predicated on his ability to guess the weather, for god’s sake. When he tries to escape Punxsutawney for the first time and is told the roads are closed from a blizzard (that he failed to predict), he responds tellingly: “I make the weather!”

The importance of choice is directly tied to its capacity to affect, whether that be someone’s life, the world or tomorrow’s lunch. So, as the reality of Phil’s situation really begins to sink in, he realizes that, without a tomorrow, his decisions have no consequence — and that choice becomes arbitrary, and life meaningless. Whether he stays in bed all day or kills himself before breakfast, Phil will wake up in the same position, on the same holiday, with the same groundhog weatherman demanding his attention.

What follows is a sort of nihilism equal parts depressing and liberating. Without consequences, he swaddles himself in hedonism, chasing women whose life stories he learned the day before, gleefully taunting the police and eating like (or because) there is no tomorrow. With literally all the time in the world, he can learn everything about his new eternity — the names of his neighbors, their trials and tribulations, the order of the day’s events down to the second — and begins to refer to himself as a god. Then, by his own estimation, he successfully kills himself more times than he can count. On and on the carousel spins. The movie’s director guessed Phil spent the equivalent of a decade inside Groundhog Day, while other estimates have put the number closer to 30 or 40 years.

Now, nihilism is not traditionally the province of optimists. Nietzsche was not known for his sunny disposition and, for the most part, watching Phil devolve doesn’t impart any warm, fuzzy sentiments about the nature of humanity. But in the course of Phil’s deeper and deeper loop, we begin to sense a change.

In one of the movie’s most iconic scenes, Phil (the human) kidnaps Phil (the groundhog). Pandemonium ensues. The pair leads police on a dramatic chase through town, but the moment of clarity is a blink inside the cabin of the car: groundhog Phil is sitting on the lap of human Phil, his head peering up and over the steering wheel. This implies for one sublime second that groundhog Phil is driving the vehicle. It’s the moment of absolute zen in which human Phil accepts his situation: he does not have control.

This gives us the first glimpse of plot resolution: although we have no way of knowing how he will break out of the cycle, we can guess. Beautiful female lead with wholesome personality and sunny outlook on life playing opposite the stodgy, miserable weather man? Sounds like someone needs to learn what love is!

But finding love with Rita (Andie MacDowell) takes on a different tint in the context of highly specific eternity. Phil might have had 30 years of real-time to achieve self-actualization, but the people he’s surrounded by have no way of knowing he’s any different February 2 than he was on February 1. It’s in that colossal difficulty of Phil’s task — convincing someone who knows him that he has changed and getting them to fall in love with him — that we see the totality of human love.

He starts with courtship. Phil presents himself as a progressively more perfect partner to Rita every day, slowly learning her quirks and desires so he can effectively fool her into loving him by virtue of coincidental similarity. It doesn’t work.

Then, in a moment of near-vulnerability, he breaks down and explains his situation, using his omniscient knowledge of the world around him to show something is wrong. That doesn’t work either, because his conception of love swirls around himself. Rita herself tells Phil in the town diner: “You are egocentric! It is one of your defining characteristics!”

It’s only when he looks outside of himself and back at the town around him that he stumbles upon higher forms of love: love for others, love for community, love for Punxsutawney, all manifesting in acts of service. Rita notices how he’s changed because he isn’t doing it for her. And it’s against that backdrop of nihilism, as he commits to love when he knows there’s no incentive to, no measurable impact for tomorrow, no photograph to commemorate the occasion, that the loop finally breaks.

“Groundhog Day” shows us that life matters to the extent that we understand it doesn’t. In truth, we do not have to be kind, we do not have to be good. But having that understanding does not keep us from the immediacy of a present moment — from helping each other, from seeing the best of wherever we happen to be. We will always have the choice to be kind, and it is in the choice to fill out the contours of connection for no reason at all — love without condition, friendship without benefit — that we find the very best of what it means to be human.

Header illustration by Nick Anderson, Miami University

NO COMMENT