Wet Carpets and Wedding Rings

by Dylan Van Sickle

I never wanted to audition for that play; my friend just needed a ride. I had just finished a three week stint in the ensemble of another show, and I had no real intention of going back for a while. But, I was 19, and this was Topeka Civic Theater and Academy. I grabbed a script, filled out an audition sheet, and soon found myself deep into the weighty role of THE COLLECTOR in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire.

Now I’d be lying if I claimed that time stopped, or I knew at first glance, or some cornball cliche like that. Truth is, when I met my future wife, I don’t even think either of us said a single word to one another. Pleasantries were exchanged later, in the safety of social media once the cast list was posted.

Our characters had titles, not names. I was cast as SAILOR, and she was the most wholesome PROSTITUTE on either side of the Mississippi. It was a match made in theater heaven.

Rehearsal time for our roles were scarce, but we made the most of it. Well, socially at least. The fight scene we rehearsed would never be fully realized, and the few lines we had, mostly off-stage, were hindered by general mischief and laughter.

We ordered a pizza, played board games, and talked from the second we arrived to the theater to the second we left. We met for a run once, but ended up walking instead. She even helped me pick out my first, and only, pair of Jordans. Oh how well-suited for domestic life we were!

But we really weren’t, at least not yet. Until one of us could muster up the courage to make some sort of move, our relationship was destined to remain in limbo. My big chance came soon enough when she offered to host a makeshift cast party at her new apartment. And by new, I mean just-got-the-keys-that-day sort of new. There was no furniture, no food, and the carpets were still damp from being steam-cleaned earlier that day.

We did have booze, though, and a respectable amount of Taco Bell to entertain us all. The two of us, for some alcohol-inspired reason, were comparing cheerleading routines from high school when the door to her bedroom shut behind us. We somehow went from cheering to hugging, and hugging to kissing, without any courageous act by yours truly. It was all her; graceful, with a healthy blend of assertiveness and love.

She was exceptional and pure, and I was just lucky enough to make her laugh. I told her she would regret everything in the morning, but that morning, thankfully, never came. Instead, we hung out again the next day, and nearly every day after that before taking our dog and off-brand television to start a new life together in Chicago.

Our next “first kiss” would come roughly six years later, this time trading the charm of those wet rental carpets for the grandeur of Lake Tahoe. Our new roles as HUSBAND and WIFE, however, are familiar. We still order pizza, opt for the walk, and perform the occasional cheer. All complete with enough laughter and conversation to turn two small parts into a lifetime of little moments.

I Love Dogs

by Brendan Pedersen

My mom texted me on a few weeks back. She’d tagged me in the comments section of a Facebook video — arguably the mom-liest thing she had ever done — saying it would remind me of Wrigley.

I was working and didn’t respond, and I eventually forgot about it. I realized weeks later that I had never seen a notification, which I think means my untagged name is sitting somewhere, plastered to the bottom of one more dog video being pushed down into the newsfeeds of yesterday under the crush of a bazillion other dog videos.

Wrigley was my dog: a yellow labrador nearly as wide as she was tall, secretly a polar bear with a faint resemblance to a U-Haul van. She stopped being a dog last June and has since become every dog. I see bits of Wrigley in the terrier running down my block with booties, the Frenchie bundled up in a shoulder bag on the CTA, the mutt doing horizontal cartwheels through the snow the second he’s been let off the leash.

I love dogs, and I loved mine more than just about anything. But as Wrigley got older, slower, started to avoid stairs, the rest of the world seemed to speed up. Once she was gone, suddenly, everyone loved dogs: “doggos run the internet now,” the BBC declared last January, and NPR published a guide on “Doggos” to explain the vast lexicon devoted to puppers and good boys. It was as if a point of singularity had achieved an instant, critical mass, with no choice left but to explode out and saturate every corner of my digital life. It was nice, in a way, and sad.

My family probably won’t get another dog; my youngest brother only has a few years left of high school, and both my parents work full-time. Who knows when I’ll be able to support one of my own. But in the meantime, I’ll keep churning out dog gifs to my loved ones, smiling at furry strangers walking past and being the dog-at-the-party’s best friend. Between all the doggos, pupperinos, clouds, fluffers and boofers filling up my newsfeed, there’s plenty of love to go around.

Like Mother, Like Daughter

by Marissa Nelson

In kindergarten, mom and I had the same haircut; straight dirty blonde strands curled inward at the bottom, just above our shoulders. Neither of us had naturally straight hair, though. So mom spent each morning working against mother nature, first pulling her hair taut while I ate cereal curled up in her bed — and then mine. Gripping her white countertop powdered with blush, I would stand as tall as my toes could stretch, peeking over the edge to see the mirror, watching as mom straightened my waves. Our matching locks and tendency to dress alike in loose denim dresses emphasized our identical cheeky grins. “Like mother, like daughter,” our neighbor would say. I’d giggle. I wasn’t sure what she meant.

In middle school, mom and I grew our hair out. I wanted long hair like the girls at school and after a stressful divorce, mom needed a fresh start. We no longer got ready together. Instead I shimmied to Taylor Swift in my bedroom as I threw multicolored skirts to the ground and mom listened to Good Morning America in hers while applying an auburn shade of lipstick. Mom wore blouses now and I wore pink and brown skirts with leggings. On Saturdays, mom and I ate all we could at the Pizza Hut Buffet. We’d laugh as we chewed our fourth round of cinnamon sticks one afternoon, sipping on our Diet Mountain Dew. “Like mother, like daughter,” my mom said as we left the restaurant to go shopping. “I guess,” I’d say, laughing while I hopped into the front seat.

In high school, mom left for work before I left for class. She’d knock on my door each morning to wish me luck for the day. Groaning, I’d turn away from the door using my pillow as a shield from the outside world. My hair was longer, a few shades darker and much curlier than hers now. I spent my Saturday nights at Pizza Hut with my friends, devouring the cinnamon sticks and chicken alfredo. Mom spent her nights watching TV at home with my stepdad. At work, my mom kept a photo of us hung on her cabinet. Her co-workers commented on how similar we look. “Like mother, like daughter,” they said. When mom told me this, I rolled my eyes. I didn’t see it.

In college I still get ready in my room, often dancing to Taylor Swift. I don’t quite know when mom gets up and she doesn’t know when I do. Feeling stagnant, I cut my hair during freshman year. It now rests just below my shoulders, a bit blonder than a few years before. Three hours away from home, no one says I look like mom anymore. Though as I get ready in the morning, dressed in a blouse and jeans, pulling straight my wavy hair, I catch a glimpse of my mother. I smile. Like mother, like daughter.

Lady of the Lake

by Madeline Happold

The lake is always better after hours. Water is a grounding substance for me, an escape from the rush hours and high rises. When feeling lost within the fervor of the city, I came to rely on the promised cadence of the waves meeting the concrete.

For my first two years in Chicago, I lived walking distance from the edge of Lake Michigan. I had easy access to the Lakefront Trail and some of the it’s best attractions, per se — Fullerton Beach, the Diversey Harbor, North Pond, the swaying willow trees that lined the trail. I would spend many nights walking to the water’s edge alone, looking out from the boardwalks towards a twinkling cityscape. With heavy steps I would tell myself how damn lucky I was to be spending my formative years in such wondrous chaos that is Chicago.

The lake was there for me when I got stood up on a date. It was there for me in the ice-slick winter. It was there for me, dandelion scattered, when I lost my keys in the changing nature of spring. It was there for me when I needed an escape from myself.

There is something about water that promises renewal, clarity. I find it to be my sanctuary, where I can walk along its cement staircases and gaze out to the midnight blue. Below, I wrote an ode to the lakefront in an effort to describe my affinity:

Little brings me more joy

Than the tumbling of waves

Against the shoreline.

I listen and I feel my body

Flow with its movements

Taken with the wind

Warmed by the sun

Controlled by the moon.

Water is so smooth

Yet mighty in its movements

I want to be like water

I want to be shapeless.

I want to roll like water

I want to slap like water

I want to be crystal clear blue

I want to be pitch black murk.

I want to be so captivating

That people stop what they are doing

Just to see me

Just to sit near me,

Feel my presence is enough.

It is so easy for me to slip into sorrow

To wallow in the shallow end or

Drown in the depth.

But holding onto this happiness

Explaining this ecstasy to myself,

Saying it does not have to leave,

It is found somewhere within me,

That is the hard part.

Water may flow and tides may change

It may shift and move and alter but

It never leaves.

Grounded in nothing.

Holding its own.

I want to be formless, unmoving

Strong yet soft, bending and shapeshifting

As fluid as water.

Nesting

by Megan Stringer

When she invited me to her 21st birthday dinner, she told me she didn’t need gifts, but wouldn’t say no to baby supplies. Then came the Thai food, the family and their significant others and the long-term boyfriend I’d never met from a year-long study abroad trip. She’d left for Thailand after an argument had driven the two of us — best friends since childhood — apart.

There’s one memory in particular this reminds me of, although I’m not sure why. Her, Ali, and myself were laying on Ali’s bedroom floor, on that narrow space of carpet between her tall, white bed and the bright lime green wall — the side without the window. We’d press our backs hard against the ground in order to lift our legs in the air and dangle them. Someone would play music from YouTube on their iPod Touch — in this case, the song “To Build a Home” by the Cinematic Orchestra, which I believe we found from absorbing ourselves in Harry Potter fan culture at the height of our middle school years. We’d watch some tribute videos complete with dramatic music on someone else’s perspective of this made-up world we decided to love. But “To Build a Home” meant a lot more than Harry Potter and wizards and magical orphans to us — it represented the home we once made within each other, within our overbearing early teenage livelihoods.

I think even through high school, there was a part of me that always saw our friendship as the one where we’d find stray sticks and use them as wands on the blacktop, daring to shout spells of witchery behind Catholic school grounds. As we’d flail our arms we’d talk about how one day we’d get out of town, move to a more metropolitan city, live together in an apartment high up with a view. I didn’t think it at the time, but now I’m sure most teenagers do this. One day, her teenager will too. And she’ll both love and hate her for it.

We’d sit there kicking our feet in the air, listening to this song — I held on as tightly as you held onto me / And, I built a home / For you / For me. Maybe we’d shed a tear, and talk about how special what we had was. It was special because it was ours and not our parents’, something that used to mean a lot at that age. We were so desperate to find our homes outside our parents’ walls and traditions, but I don’t think we realized yet that you had to build your home whenever and wherever you could, as a means of connection but also survival. We wouldn’t find it, or stumble into it. Building something takes patience and choice.

This is something she’s doing for herself now, and for that tiny human inside of her. Building a home.

This is a place where I don’t feel alone

This is a place where I feel at home

And So Spring Turns Into Summer

by Emma Krupp

When we moved in together last June, my roommates, Annie and Meg, were what I might call acquaintances-plus — people I was friendly with, but certainly not friends with. They had been close since freshman year; I was a girl Meg met at a journalism panel in the spring. We all decided to live together anyway, hauling our things one by one up two flights of stairs and into a bright, empty apartment on Oakdale Avenue.

Here’s a truth that’s unfolded over the past few months: I don’t remember how my I spent my days before I came home to Meg hunched over her desk (brow furrowed and upper lip protruding slightly, always), or fell asleep to the sound of Annie’s footfalls roving around the apartment at 2 a.m. I don’t remember what it was like to not be surrounded by people who curl up next to you when you look especially happy or especially sad, who know which type of tea to make when your face starts to crumple. And that’s just a snippet of what it’s like to live with Annie and Meg. Sometimes I see them sitting there in our dimly lit living room, doing something as simple as lounging on the couch, and I think, Ah, so is this my life now?

I spent the first two years of college plotting to get out of Chicago, and 19 years before that plotting to get out of Illinois. Now, as graduation’s eventuality creeps closer and closer, I look at the city — up high in a building downtown, or tucked away on some new strip of beach — and feel this murky, clutching sensation near the bottom of my sternum. I haven’t seen enough, I haven’t done enough, and it would be unbearable to leave. This is because I love Chicago, of course, but it is also because of Annie and Meg.

Right now I’m in a class on Japanese women’s writings, studying the great waka poetry of the Heian Period just over a thousand years ago. The poems are these incredibly tragic musings on how love is most beautiful when it’s temporary, temporary like the seasons, temporary like cherry blossoms — plump, pink and transitory — fluttering to the ground at spring’s end. It’s senior year, and I have always had a maudlin streak. You can well imagine, perhaps, that I’ve fixated on this metaphor.

But at the same time, I wonder: Why does this have to be temporary? Can’t you build a life out of living room dances and bleary all-nighters and cups of hot coffee left as offerings outside closed doors? In fleeting moments, I’m positive I could spend the rest of my days here — not in this apartment on Oakdale Avenue, but in a small home built by women who try their best to take care of each other’s hearts.

I know June is coming, and when it does, I might have to leave whether I want to or not. And even if I don’t leave, they will, eventually, and the city will change, and the streets won’t look the same. I know this, and I also know there is no great tragedy in the changing of the seasons. But my life here is beautiful and I wish I could bottle it up, preserved and soft like so many cherry blossoms pressed in paper.

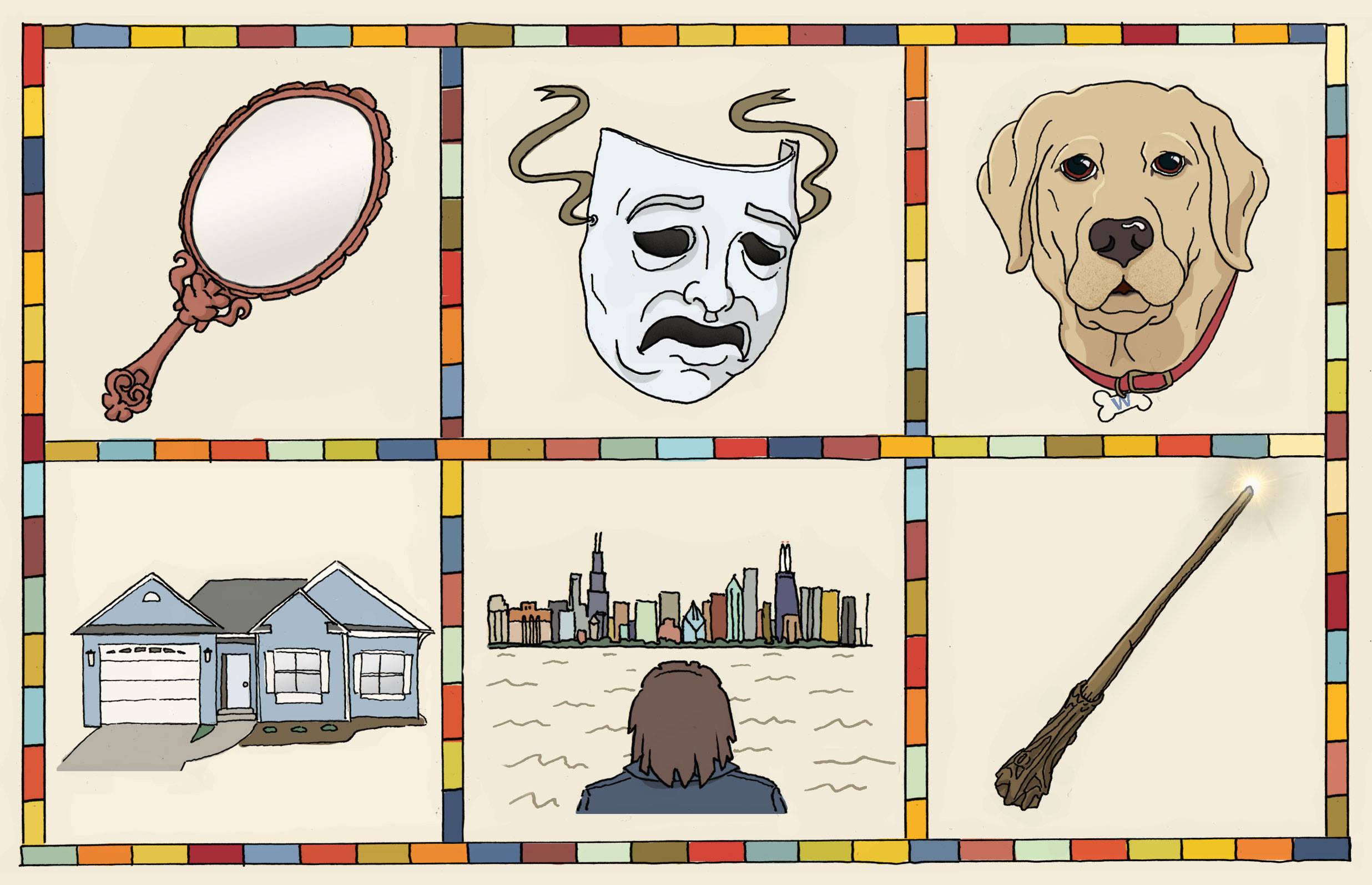

Header illustration by Nick Anderson (Miami University).

NO COMMENT