“My name is Dennis White. I’m 63 years old. And my brain is dying.”

Dennis White, a Massachusetts resident, was diagnosed with a terminal neurological illness called Primary Progressive Aphasia. The illness affects the brain, impairing the speech and memory of those who have it over time. In a 2015 documentary where White talks about his struggle with the disease and his death, he speaks his sentences slowly, as if he is deliberately thinking of each word that comes out of his mouth.

“I never thought about death until I was diagnosed and then it suddenly became urgent,” he says. “And I want to go out with a bang, like I’ve lived most my life.” Cue White’s inspiration: an (end of) life-changing TED talk about the Infinity Burial Suit.

The Infinity Burial Suit, created by entrepreneur, artist and designer Jae Rhim Lee, is a biodegradable garment worn by someone who died to help the natural decomposition of their body. According to the website, “the Infinity Burial Suit has a built in biomix, made up of of mushrooms and other microorganisms that together do three things: aid in decomposition, work to neutralize toxins found in the body and transfer nutrients to plant life.” It is currently also one of the most environmentally friendly ways to get rid of a dead body.

In the wake of his diagnosis, White and his family found themselves needing to prepare for his rapidly approaching death, and after seeing the TED talk about the mushroom death suit, White reached out to Lee to be the experimental subject for her new product.

The customized suit, which Lee refers to as “ninja pajamas” in her talk, comes in black or white and completely covers the body, including the hands and feet. It also includes a hood that covers the face but can be removed for postmortem viewings. The biomix is infused in crocheted lines, which look like roots or veins on the suit.

With such a new product, White, his family and Lee faced several logistical issues, such as fitting the suit to his body, planning a funeral that would appease his whole family and finding a cemetery that would accommodate his unusual burial. For some reason, it’s hard to imagine anything other than literally burning a person’s corpse or putting it into a human-sized jewelry box and burying it like a morbid time capsule.

In fact, modern funeral practices didn’t start developing until the Industrial Revolution. An article by criminal justice scholars Virginia Beard and William Burger in the “Omega: Journal of Death and Dying” says that before the end of the 17th century, funerals were small, short and informal with nothing but the family and a simple wooden casket.

The rituals became more ceremonial in the United States as cities began growing economically and culturally. Scientific and industrial innovations allowed for a cultural shift in death views and practices. People had railroads and medicine, and as lives became longer, so did the funerals.

This, however, also began further dividing classes with the more wealthy people burying their loved ones on plots in churches and “commoners” using family-owned farms and cemeteries. Basically, death practices became a way to show wealth and affluence. Around the Civil War era, people also began using metal coffins, headstones and flowers to show their status.

The ritual evolved, and what we think of as the “traditional” funeral — embalming, visitations, burials — became the norm in the 1920s, and ever since, the funeral industry experiences significant changes each time society undergoes an increase in wealth.

According to the Parting, the average funeral today can cost anywhere from $7,000 to $10,000, and the cost grows higher each year. The Bureau of Labor Statistics cites that funeral expenses rose 227.1 percent between December 1986 and September 2017.

The Infinity Burial Suit costs $1,500. Most people in the United States, however, choose a funeral and burial or cremation, even with other options available.

White died on September 22, 2016 in Woburn, Massachusetts, at 64 years old. His body, wearing the Infinity Burial Suit, is buried on a plot in Maine.

In the midst of covering all of the logistics, White’s family entered unfamiliar territory: talking frequently and openly about the impending death of a loved one. They found themselves needing to balance their emotions and logic while planning his burial.

“In some respects, dealing with the logistical things is, I think, a way to cope with it without having to deal with the emotional half,” said White’s son, Marshall White. “I figure there will be plenty of time for that.”

For the months after learning about Coeio, the company that manufactures the Infinity Burial Suit, almost all of my conversations (both reporting-related and otherwise) started with the question, “Would you ever get buried in a mushroom death suit?” The general responses were blank stares and confusion. As someone who has never felt uncomfortable about death — a death enthusiast, even — I thought the answer would be a unanimous “yes.” It’s cheap, practical and good for the environment. But people seemed a lot more reluctant to challenge death traditions than I expected. Cremation or coffin; it’s weird to think of anything else.

As a society, we tend to avoid talking about dying although it’s a reality every person will have to face — the situation is inevitable. But speaking with people who are routinely more open about death can give a peace of mind about the subject.

To get a grasp on the lengths people will go to for a fancy grave, I took a tour of Graceland Cemetery with some other death enthusiasts on a cloudy October morning. Adam Selzer guided our group around the famous cemetery, giving us facts and stories about some of the plots. Red and yellow leaves scattered on the walkway and crunched under our shoes as he led everyone from one intricate grave to the next.

The cemetery stretches 119 acres, and buried six feet beneath its soil are notable names like famous German-American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Hall of Fame Chicago Cubs baseball player Ernie Banks and Charles Dickens’ “no-good” (according to Selzer) brother Augustus.

Selzer is a Chicago-based author and tour guide, and a field agent for Atlas Obscura. His research and area of interest primarily center around the history of ghost stories, grave robbing and other aspects of the bizarre and supernatural (he also has a range of young-adult novels, with my favorite title being “How to Get Suspended and Influence People”).

Along with writing novels and nonfiction history books on the supernatural subjects, Selzer gives cemetery tours where he talks about notable graves and people buried at the locations. His line of work requires him to constantly be surrounded by the concept of mortality, and since the topic is omnipresent in his work, Selzer finds it easier than many to speak more openly about death.

“You kind of get jaded to it after a while,” Selzer said. “You can’t let death have too much power over you. It’s got all the power over you that it needs, but if we laugh at it a little bit, we can keep it at a distance.”

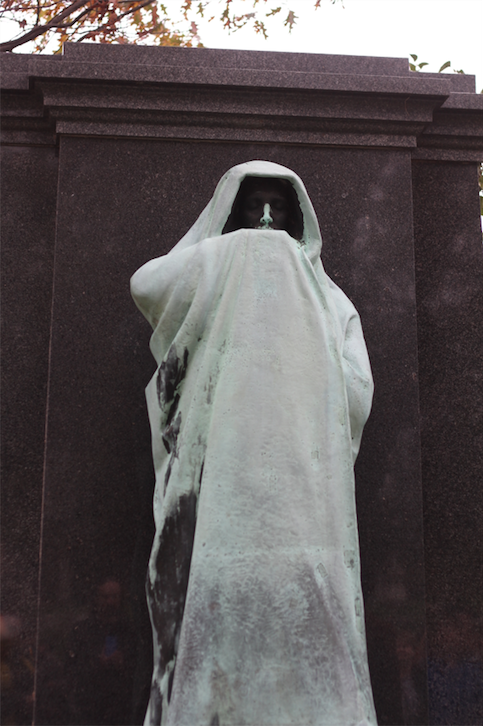

Adam Selzer stands in front of the Eternal Silence statue in Graceland Cemetery as he explains the monument’s history to people on a tour of the cemetery. (Rachel Fernandez, 14 East)

Near the entrance and one of the first stops on the tour is a grave marked by an ominous bronze figure worn a minty green by time. The name of the statue is Eternal Silence but is sometimes referred to as The Statue of Death, and legend has it that if you look into his face, you can see your own death.

As the tour continued, we followed his lead as Selzer stopped in front of a gravestone with the name “MANUEL” displayed on the front for 40-year-old anesthesiologist Christopher Manuel, who died in 2005. On top of the death-stone sat an iron figure of a young man playing a flute. Inscribed on the side of the grave were lyrics from the Donny Hathaway jazz standard “For All We Know.”

“It always makes me think, ‘What do we want on our gravestones?” Selzer said. “For me, I want a bit of Fiddler Jones epitaph from the Spoon River anthology:

The earth keeps some vibration going

There in your heart, and that is you.

And if the people find you can fiddle,

Why, fiddle you must, for all your life.”

He adjusted his thick-rimmed black glasses that had the phrase “nothing is real” written in white on the sides (an intriguing Beatles reference for someone who gives cemetery and ghost tours) and shifted the crowd onto the next death display.

Death lives beyond cemeteries, though, so might as well tackle the subject in school. Kyle Nash is a professor at DePaul University who regularly teaches an online course called Death and Dying: Facing Mortality, Celebrating Life. She created the class because she felt that other classes centered around dying and death that she encountered were more didactic and taught in a way she referred to as “out there” or emotionally unattached. She had seen classes that talked about the history of death practices and how other cultures viewed death, but nothing that looked internally at how people process death.

“I believe that everything starts with us,” Nash said. “Our experiences create the filter which we take in information, process it, and then it comes back out.”

Nash’s online course aims to create a more open and honest dialogue about death. Through initiating this new outlook, Nash hopes her students become better prepared for conversations about the subject. Her course involves some of the didactic “out there” material, but she specifically formulated it to be experimental so students can learn to process feelings of loss themselves.

The students are graded through discussion boards and self-guided activities that make them think deeply about death, loss and the way they grieve because, in Nash’s experience, “it’s not a matter of if people grieve. It’s a matter of when and how.”

Mirroring the name of the course, Nash assigns her students to do something where they’re celebrating life and write a personal reflection on their experience. This could be as small as watching their favorite movie or as big as traveling to a new place.

Later on in the course, the students take the same concept, but apply it to facing mortality. They can tackle anything from starting to plan a funeral with a family member, writing a will or looking into how they would like to have their bodies disposed of after their own death.

“The key component is personal experience where people, through these exercises and discussions, are tapping very deeply into their own loss issues that may not even be related to death,” Nash said.

She finds that teaching her class online and not forcing her students to meet face-to-face encourages them to think more deeply about death and loss, since they can be more vulnerable on their own and not have to worry about getting too emotional around other students in a classroom.

Although Nash and Selzer are among those trying to change the dialogue around death, it is still a largely taboo topic among the general population.

While a class is one practical approach to getting people to create a more open dialogue about death, it’s impossible to know how anyone will respond to the situation until they are actually faced with it — and even when they are in the situation, the choices may feel overwhelming. One way people can tackle this anxiety is through hiring an end-of-life doula.

Unlike a regular doula, who is trained to assist people during childbirth, an end-of-life provides support during the process of dying. According to the International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA) doulas “assist people in finding meaning, creating a legacy project and planning for how the last days will unfold.” Their work does not stop with their clients, however, but extends to providing support for their loved ones in the grieving process.

Haley Broadway is an end-of-life doula based in Chicago whose main job is to provide emotional, spiritual and physical support to people who are dying. Broadway’s clients range in age from elderly people to children. Her goal is to make people directly facing death more comfortable with the topic and situation. Although relatively similar, her work varies from that of a hospice in that she is able to give more physical support when her clients need it.

“Sometimes people just want to be held, and that’s what it really comes down to,” Broadway said. “Being a doula offers a sense of intimacy with our clients, and that sense of being held and being loved and that sense of security is really important.”

Her support subsequently extends to the family, and she helps them cope after their family member’s death. One of her missions is to help make post-death arrangements for her dying clients. The specifics vary greatly from person to person because of culture and tradition.

“We talk about funeral plans, burial options, whether they want to be embalmed or not, cremated, whether they want to have a funeral service,” Broadway said. “We want to make sure that we talk about everything beforehand so we’re really able to advocate for them and create the space for them that they wanted.”

Broadway’s clients get an emotional pillar and a hand to hold during the most vulnerable times of their lives, and more voices are being heard as the conversations about death continue to grow, like mushrooms from a burial plot in Maine.

Header image by Rachel Fernandez

NO COMMENT